Listen to the article.

The Armenian government has embraced a comprehensive policy for the inventory, preservation, restoration, and promotion of historical and cultural monuments. This approach recognizes the economic potential of archaeological heritage, and positions it as a cornerstone of the country’s sustainable development strategy.

The Ministry of Education, Science, Culture and Sports (MESCS) reports that as of July 2024, 24,252 monuments are listed in the state registry of immovable historical and cultural monuments, organized into approximately 7,300 territorial preservation units. Additionally, 800 cultural heritage objects have received designation as newly discovered historical and cultural monuments. These newly identified or newly valued sites require preservation pending their inclusion in the state registry of monuments.

Armenia’s historical and cultural sites, both in Yerevan and across the regions, attract locals and tourists alike. Notable sites include the Garni Pagan Temple and Geghard Monastery, Sevanavank and Hayravank, Haghartsin Monastery Complex and Goshavank, Khor Virap, Amberd Fortress, Zvartnots and the Echmiadzin Cathedral, Areni Cave and Noravank, the Haghpat and Sanahin Monastery Complexes, the Seven Wounds Church and Harichavank, and the Tatev Monastery Complex. Armenia’s most iconic monuments consistently generate the highest visitor interest, as highlighted by major tourism organizations. According to reports from Armenia’s Statistical Committee, the “culture, entertainment, and recreation” sector has contributed approximately 3% to the country’s GDP over the past three years, though specific contributions within this category are not delineated. A 2014 UNESCO study further underscores culture’s economic impact, estimating its share at 3.33% of GDP, with cultural and natural heritage comprising 3% of that total. Globally, cultural tourism is one of the most popular travel trends, and Armenia’s Tourism Development Strategy identifies it as a key driver of the sector. Around 49% of both Diaspora Armenians and international visitors cite cultural tourism as their primary reason for travel to Armenia. This is reinforced by a 2015 World Bank report, which notes that cultural heritage routes remain the country’s most sought-after attractions.

The “2023-2027 Strategy for the Protection, Development, and Promotion of Culture in the Republic of Armenia” outlines ambitious plans to diversify tourist routes, extend the peak travel season, boost visitor numbers, and attract greater funding. By 2027, the initiative aims to restore 30 monuments and spotlight 50 hard-to-reach sites. While existing routes largely highlight Christian heritage, the strategy places a renewed focus on preserving and showcasing civil and state architectural landmarks, including fortresses.

Creating new tourist routes presents both promotional and infrastructural challenges. Many historic sites are at risk and require restoration—a process requiring substantial funding, professional expertise, and state support.

The Armenian government has prioritized the preservation, restoration, and economic viability of monuments. On August 29, the government decided to establish protected areas around several monuments. This initiative aims to develop infrastructure, improve surroundings, install lighting, implement ticketing, and facilitate educational, academic, informational, and cultural activities. The MESCS stated that once the protected areas and ticketing system are in place, ticket revenue will fund ongoing monument preservation and development. During discussions, Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan noted that many historical and cultural monuments have deteriorated over decades or even centuries, creating an urgent need for their preservation and restoration.

Pashinyan emphasized the importance of historical and state heritage sites contributing to state revenue where feasible. He argued that if these monuments hold state value, they should also serve as income-generating assets, reflecting a necessary shift in mindset.

A Complex Task

Armenia has over 600 endangered monuments, explains Armen Hovhannisyan, Director of the Historical-Cultural Reserve-Museums and Protection of Historical Environment (a government-run NGO). He emphasizes that ancient sites and necropolises require urgent excavations to preserve remaining undamaged artifacts and archaeological layers.

Architect, urban planner and former head of the Cadastre Committee, Sarhat Petrosyan, argues that leaving a monument untouched is sometimes preferable to improper restoration. He points out that the state has yet to develop effective mechanisms to ensure proper restoration procedures and high-quality outcomes. The legislation governing this field remains unchanged since its adoption about 25 years ago. Petrosyan acknowledges that the only significant improvement came in 2017, when monument restoration was restricted to licensed restoration architects.

While monument restoration uses both state budget funds and public-private partnerships, Petrosyan is critical of the state funding process. It follows the same principle as school renovations—the contract almost always goes to the lowest bidder. This approach is problematic because restoration work often encounters unexpected challenges that require deviation from initial plans, yet the public procurement system lacks the flexibility needed to accommodate such changes.

“The legislation should give this freedom to both restoration architects and contractors to ensure a good result,” Petrosyan says. “When restorations are funded by benefactors, at least one challenge is resolved—the architect and contractor are freed from the complex public procurement process.” He also highlights the lack of a professional framework for prioritizing monument restoration, noting that decisions are often driven by the personal interests of high-ranking government officials rather than systematic criteria.

Petrosyan criticizes the state’s approach of allocating limited funds to numerous monuments, arguing that it dilutes impact. He advocates for concentrating resources on fully restoring one or two monuments each year to ensure meaningful preservation. While Petrosyan acknowledges successful restorations like the St. Gregory Church in Aruch and the fortress of Dashtadem, he notes that unsuccessful restorations, such as the Garni Bridge, are more common.

Paradoxically, Petrosyan argues that allocating large sums for monument reinforcement, repair, and restoration can sometimes do more harm than good.

“For instance, in the case of Sanahin, little money was allocated, and thus, there was little intervention, preserving the monument’s integrity,” he explains. “Minimal funding led to minimal intervention, can’t even tell it has been restored.”

Petrosyan also points to the problem of perpetually unfinished restorations, citing the Kobayr Monastery Complex, which remains incomplete after years of work.

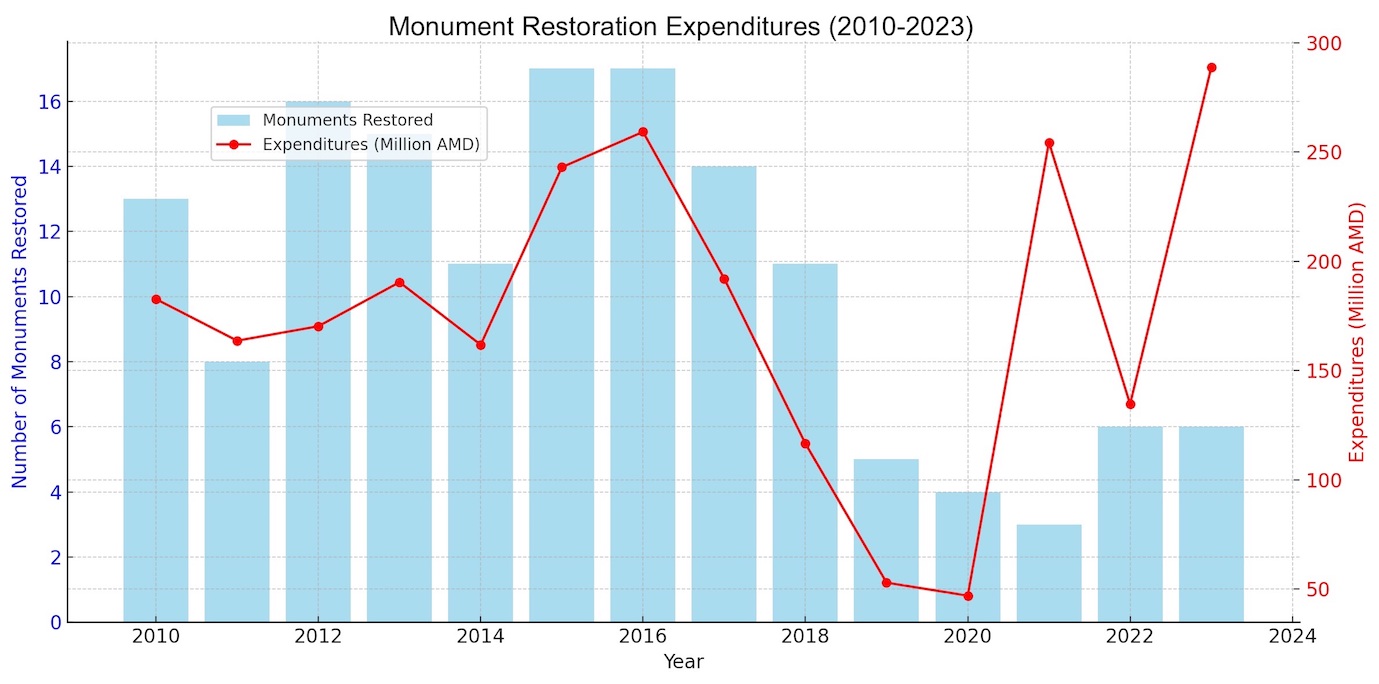

Documentation

According to data from the MESCS, in 2010, 13 monuments underwent reinforcement, repair, or restoration, with a total expenditure of 182,662,200 AMD. In 2011, eight monuments were restored for 163,625,600 AMD. In 2012, restoration work covered 16 monuments at 170,231,100 AMD. In 2013, 15 monuments were restored for 190,385,644 AMD. In 2014, 11 monuments cost 161,769,820 AMD. In 2015, 17 monuments were restored for 243,017,030 AMD. In 2016, another 17 monuments were restored for 259,203,210 AMD. In 2017, 14 monuments underwent restoration at 192,075,553 AMD. In 2018, restoration work on 11 monuments cost 116,527,800 AMD.

The sector’s funding dropped significantly in 2019 and 2020, though it rebounded substantially in 2021.

In 2019, five monuments underwent restoration work at a cost of 52,875,300 AMD. In 2020, restoration of four monuments cost 46,926,600 AMD. In 2021, though only three monuments were restored, the cost reached 254,418,700 AMD. In 2022, six monuments were restored for 134,599,470 AMD, and in 2023, restoration of six monuments amounted to 288,718,000 AMD.

Management Issues

The funds allocated from the state budget for monument restoration were 400 million AMD in 2022 and 660 million AMD in 2023. By 2027, state allocations to the sector are expected to reach at least 2 billion AMD. However, according to Sarhat Petrosyan, authorities are failing to address long-standing issues: proper planning, restoration implementation, and appropriate preservation of restored areas. Petrosyan emphasizes that successful restoration requires professional commitment from all parties—the client, designing architect, and restoration builder. Additionally, high-quality management of the monument is essential. Yet Petrosyan points out that the state’s public education efforts remain inadequate.

“Some individuals have monuments located on their property,” he says. “They often assume full ownership, not understanding that a building’s monument status means they aren’t its sole owner. Rather, it is public heritage entrusted to their care—a privilege that carries responsibility.”

Petrosyan highlights numerous instances of inadequate monument management, with Sevanavank standing out due to the commercial activities encroaching on this heavily frequented site. He stresses the need for substantial reforms, pointing out that even the term “monument” is outdated, with “heritage” offering a more inclusive and nuanced framework. He advocates for viewing monuments as integral components of their surrounding environment, rather than as isolated structures.

“For example, the Sevan Peninsula is a monument in its entirety, not just the church or the Writers’ House. Therefore, we must treat this historical heritage with care, determining appropriate locations for parking and commercial activities. These considerations should all be part of the monument’s preservation plan,” he explains.

Monuments face recurring incidents of damage and desecration. In 2023, authorities recorded 85 violations at monument sites, including three cases of vandalism. Of these violations, 30 resulted in criminal charges.

In January 2024, vandals struck again at the Karmir Berd site—an archaeological monument dating to the 2nd millennium BCE—where they dug holes and damaged stone walls.

In response, authorities are implementing preventive measures including security cameras at select monuments, local monument preservation initiatives, educational programs, seminars and public classes.

Summer schools provide opportunities for students to visit monuments with their teachers and learn about historical landmarks. Additionally, new informational and directional panels are being installed at sites to help visitors recognize protected monuments. This signage is crucial as some citizens unknowingly damage monuments not realizing they are in protected zones.

Promotion Beyond Borders

Armenian intangible cultural heritage must be promoted both domestically and internationally to support the country’s sustainable development, economic growth and global recognition. Armenia promotes its cultural heritage internationally by participating in various events and seeking UNESCO recognition.

The country has three monument groups included on UNESCO’s World Heritage List: the monastic complexes of Sanahin and Haghpat, the Geghard Monastery and Azat River Valley, and the Etchmiadzin churches together with Zvartnots Cathedral.

According to UNESCO’s regulations, a monument must first be included in the Tentative List. Armenia currently has four monument groups included on this list: the archeological site of the city of Dvin, the monastery of Noravank and the Upper Amaghou Valley, the basilica and archeological site of Yererouk, and the monasteries of Tatev and Tatevi Anapat. A new application is being prepared to include the vishap stones of Mount Tirinkatar in the Tentative List. These archaeological monuments represent a unique cultural phenomenon found only in the Armenian Highlands.

While funding for the restoration and preservation of monuments has increased over the past three years, assessing the impact and long-term benefits of these investments remains a challenge. Moving forward, it is crucial to prioritize not only the completion of restoration projects but also the sustainable preservation of these monuments to ensure they endure for future generations.

Also see

The Revered and Overlooked Legacy of Rafayel Israelyan

Rafayel Israelyan, one of the most prolific architects of the Armenian world, left an enduring mark on Armenia’s architectural landscape with his visionary designs that included memorials, fountains, bridges, churches, government buildings, and more. Despite his remarkable contributions, his legacy is underappreciated.

Read moreYerevan’s Christian Heritage

Yerevan’s Christian heritage has usually been overshadowed because of its proximity to the Holy See of Ejmiatsin. The first accounts about churches in Yerevan are from records dating back to the Third Church Council of Dvin in 607 AD.

Read moreDiscovering Armenia: The Potential of Archeological Sites and Obstacles to Excavations

Today, there are ongoing excavations of archaeological sites throughout Armenia, including the excavation at the site of the ancient Armenian capital of Dvin. Despite the country’s huge archeological potential, specialists in the field often face numerous barriers.

Read moreHeritage and the Contemporary

When emphasizing the preservation of historic structures and their integration into unban life, we should keep in mind that heritage should not be perceived as only architectural heritage and we should not think that it is only the physical heritage that is endangered.

Read moreZones of Entrapment: Yerevan’s 2800th Anniversary Park and the Tyranny of Taste-Fullness

In the context of autocratic, oligarchic or committedly neo-liberal regimes which continually propagate a coercive and incarcerating model of urban planning, the multiplication of such spaces as the 2800th Anniversary Park of Yerevan is organic, writes Vigen Galstyan.

Read moreNotre Heritage? The Uncomfortable Truths of Cultural Legacy in Peril

The fire that severely damaged the Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris highlighted how indispensable art is for humanity and exposed the fragility of all cultural legacy. It also indicated the profoundly unbalanced ways through which the global community has come to evaluate the intellectual production of different cultures and nations.

Read moreKond: A City Within a City

A tucked away city within a city, the district of Kond in Yerevan has a rich history and a promising future only if authorities undertake a large-scale restoration. What are the stories of Kond and what does the future hold for one of the oldest quarters in the country’s capital?

Read more

As an Architect I appreciate Armenia’s amazing heritage sites. Your tourism industry has great potential. Maintaining the heritage sites is essential. I understand your observations regarding Contractors. I worked for a Government body in London. It was common for Contractors to submit a low knowing that they would profit from change orders. The Architects should be allowed to to select the most reputable Contractor even if they are not the lowest bidder. Contingency sums need to be added for unforeseen conditions especially with ancient monuments.