Melik-Aghamalyan Family

Kond was also the residence of the aristocratic Melik-Aghamalyan family. According to Shahazis, the family owned numerous buildings and land in the territory of Kond. For several centuries, Surb Hovhannes was known as their ancestral church and the family donated money to rebuild it after it was destroyed in the earthquake of 1679; their name is inscribed on one of the walls of the church. Famous for their participation in several battles in the territory of Yerevan, the Aghamalyans were considered one of the richest and well-known families of Old Yerevan but for the current residents of Kond, the Aghamalyans are famous for their kindness and generous support to the survivors of the Armenian Genocide. As Kondetsis recall, the Aghamalyan family provided shelter to the orphans and immigrants from Western Armenia.

However, the descendants of the Aghamalyans suffered tremendously during the Stalin repressions. The last member of the aristocratic family, Sasha Aghamalyan was ousted from his home in Kond during the Stalin purges and died in a small basement apartment.

Currently, there is a gold watch kept in the Yerevan History Museum that was presented to the Melik-Aghamalyans from Russian Tsar Nikolai I for their contribution to the Russian-Persian war. Their princely residence constructed of black tufa stone, standing half-ruined near the entrance of the quarter, is the only reminder of the family’s existence.

The Mosque

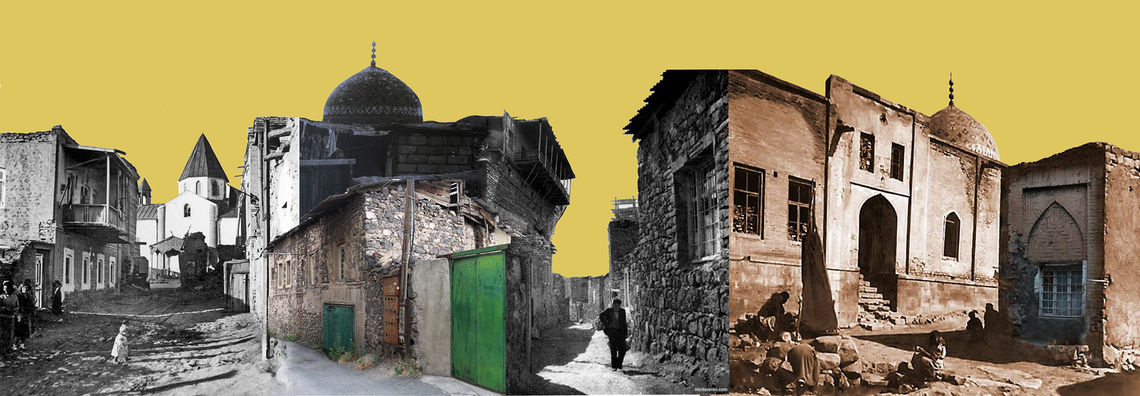

Dating back to 1687, the Thapha Bashi mosque, the remnants of which only remain in Kond is listed as a historical monument and is protected by the Armenian state. When Muslims left Armenia in the beginning of the 20th century, the mosque became a residence for many survivors of the Armenian Genocide. One can still see the influence of Persian architecture that fortunately remain intact. As the residents recall, the “huge dome” of the mosque collapsed more than two decades ago, several years after the Spitak Earthquake.

Present-Day Kond

Though one can get lost among the dozens of small and narrow lanes of Kond, the district does have three main streets: Rustaveli, Simeon Yerevantsi and Kond. Many houses are covered in vines, while simple rural-style communal springs appear at corners of its narrow meandering roads.

While the novelty of the district often attracts the curious, residents of Kond feel ignored and abandoned by the municipal and national governments. Conversations with locals reveal widespread discontent with the former authorities who for the most part were not able or refused to address issues faced by the residents – from lack of proper services to poor road conditions. An older woman living in Kond, a supporter of Karen Demirchyan, the late Soviet Armenian leader and native of Kond who became parliament speaker after independence wanted to highlight the socio-economic conditions of the district, hoping for some reaction from municipal authorities.

A Soviet era building now stands entirely abandoned in the middle of Kond. It used to house a library and a pharmacy until it became a dumping ground, just like the public toilet close by.

Like Demirchyan’s parents, many of the residents of Kond are descendants of Western Armenian refugees. Many genocide survivors from Van, Mush, Erzerum and elsewhere settled in Kond after 1915. Though Muslims (mostly Azerbaijanis and Persians) lived in Kond in the early 20th century, only a few remained by the late Soviet period. One resident says he was friends with his Azerbaijani neighbors, some of whom were “thieves in law.” He says Turks, Yazidis, Jews, and Boshas (Gypsies) formerly lived in their quarter.

Harutyun, a 68 year-old retired sculptor, is a typical Kondetsi. “We had several opportunities to leave Kond, but we stayed here,” he said. Named after the resurrection of Jesus (Harutyun is Armenian for resurrection), the old man said he speaks baradi lezu, simple language, staying true to his origins. The locals are well aware of the district’s status as the only surviving part of “old Yerevan.” A local guide, a woman in her 30s, pointed to several houses. “These are from the 1920s. You won’t find buildings this old in Yerevan,” she claimed. A neighbor reacted, “Not 1920s, but older. Both my grandmothers were born in these houses in 1908 and 1912.”