Listen to the article.

The statues and monuments a city, especially a capital, puts in its public spaces are not just works of art, but reflect the taste and politics of those periods when they were placed. Yerevan’s numerous statues serve as a living historical archive, chronicling its political transformation from a small provincial town to a large national capital. Many of its monuments tell a story of power and memory—from Communist figures and monuments, to memorials honoring national heroes, to statues celebrating international friendships and commemorating historical tragedies.

Communist Figures and Symbols

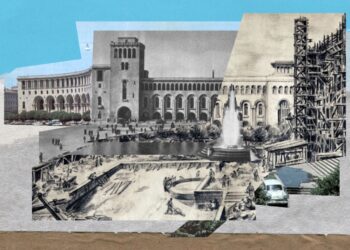

During the Tsarist period, Yerevan, then a modest provincial town, did not have any major statues.[1] That changed after the Soviet takeover in 1920, when the city began to see its first public monuments dedicated to Communist revolutionaries, both Armenian and non-Armenian, who were regarded as pioneers and martyrs of the cause.

These early figures were soon followed by more monumental statues of perhaps the most prominent Armenian communist, the Baku Commune leader Stepan Shahumyan (1931), and later, Soviet leaders Vladimir Lenin (1940) and Joseph Stalin (1950). Of these, only Shahumyan’s statue survived the collapse of the Soviet Union. Stalin’s was taken down in 1962. The “Great Leader” was replaced with the equally monumental Mother Armenia, standing on the enormous pedestal in Victory Park. Lenin’s statue, which once dominated what is now Republic Square, was dismantled in April 1991 and the severed head along with the body are now preserved in the shared courtyard of the History Museum and the Museum of Literature and Art.

While Shahumyan’s legacy remains ambivalent and largely overlooked, Alexander Myasnikyan, a prominent leader of Soviet Armenia in the 1920s, is better remembered and generally viewed in a positive light. The removal of his statue near Yerevan City Hall, erected in 1980, has not been seriously considered and was recently restored by the government. Myasnikyan is often seen as one of the “good Bolsheviks” who contributed to the country’s development without implementing repressive policies.

Another key Bolshevik whose statue still stands—for reasons that remain unclear—is the early Bolshevik Suren Spandaryan. His monument was erected in 1990, just as the Soviet Union was beginning to unravel, in the central square of Yerrord Mas in the Shengavit district. That square, along with the adjacent metro station, is now named after Garegin Nzhdeh, the nationalist commander revered for keeping Syunik (Zangezur) a part of Armenia. Bizarrely, when in 2016 authorities decided to honor Nzhdeh, his statue was placed near Republic Square while Spandaryan’s statue remained in Nzhdeh Square.

Other communist-linked monuments continue to exist undisturbed. A classically styled monument from 1950 near Yerevan Lake is dedicated to the 30th anniversary of Armenia’s Sovietization, while the monumental obelisk on the top of the Cascade from 1967 is dedicated to the 50th anniversary of the October Revolution that brought Bolsheviks to power in Russia. Nothing speaks of its original symbolism and many, if not most, locals are not aware of its Communist linkage. When the Yerevan authorities recently announced their plans to complete the Cascade, they called the obelisk a “monument to the 50th anniversary of Victory”, reflecting how its original dedication has largely faded from public memory.

WWII Heroes

As the initial revolutionary fervor faced, Soviet patriotism took center stage, and monuments began to highlight Armenian contributions to the Soviet cause rather than to Communist ideology itself. In the 1950s, busts were erected honoring three Armenian heroes of World War II, referred to in the USSR as the “Great Patriotic War”: pilot Nelson Stepanyan, sergeant Hunan Avetisyan, and colonel Simon Zakyan. Armenian pride in its wartime legacy persisted after independence, leading to the placement of large statues of high-ranking Soviet Armenian generals. These include Marshall Hovhannes Baghramyan’s equestrian statue in front of the American University of Armenia, Admiral Hovhannes Isakov’s monument near the U.S embassy, and Marshall Hamazasp Babajanyan.

Pre-Soviet and post-Soviet heroes

The removal of Lenin’s statue from Republic Square in 1991 symbolized not only the end of an era but also the broader soul-searching Armenia faced after independence. For a time, many advocated for moving the fine equestrian statue Sasuntsi Davit (David of Sassoun), the legendary epic hero, from the train station in Erebuni to the square. This could have been an acceptable solution due to his apolitical nature, but it never materialized. Lenin’s place remains vacant to this day. Instead, three statues of prominent statesmen have been erected nearby: Vazgen Sargsyan, Garegin Nzhdeh, and Aram Manukian. This scattered approach reflects an enduring ambivalence over who might be considered the definitive national hero. In the end, post-Soviet Armenia has yet to settle on a single figure worthy of symbolically replacing Lenin.

In contrast to Manukian and Nzhdeh, who are early 20th century heroes, Vazgen Sargsyan, whose bust was unveiled near Republic Square in 2007, is a contemporary figure. Something resembling a state-sponsored cult of personality has developed around Sargsyan since his death, evident in his prominence in public commemorations and official narratives. Buried next to General Andranik at the Yerablur military cemetery, he was a towering figure in Armenian politics in the 1990s and has been glorified as a national hero since his assassination in parliament on October 27, 1999. As Defense Minister, he has been credited with establishing the Armenian armed forces and victory in the first Karabakh war.

That the late Soviet period, especially after Stalin, continues to be viewed somewhat positively is evident in the statues of two local Communist leaders, Anton Kochinyan and Karen Demirchyan, erected in independent Armenia. Both men, especially Demirchyan, are often remembered as “men of the people” under whom Armenia thrived. Demirchyan’s legacy, however, extends beyond the Soviet period. In the post-independence era, he returned to the political stage, forming a powerful alliance with Defense Minister Vazgen Sargsyan. The two rose to lead Armenia’s legislative and security apparatus, Demirchyan as speaker of parliament, before being assassinated together in the 1999 parliamentary shooting.

Women

Yerevan has remarkably few public monuments dedicated to women—and none that could be considered a “proper” statue. The only representations are two busts on the tombs of poets Shushanik Kurghinyan and Silva Kaputikyan, and an abstract memorial to diplomat Diana Abgar in the small park that bears her name.

The gender imbalance in Yerevan’s monumental landscape reflects broader patriarchal patterns in political and cultural commemoration. While female allegories like Mother Armenia are celebrated as symbols, real women, historical figures of influence and accomplishment, remain largely absent from the public space, mirroring the traditional underrepresentation of women in leadership positions.

Nevertheless, there are more than a dozen statues of fictional female characters. The largest and most prominent is obviously Mother Armenia in Victory Park on the Kanaker plateau overlooking central Yerevan. Replacing Stalin in 1967, it is the female personification of the country that was not uncommon in other Soviet republics, including Georgia and Ukraine. Other statues and sculptures include depictions of a girl with a jug (1938), a girl from Van (1975), a woman from Karabakh (1985), the mythological figure Lilith (1994), Mother of God (2000), a muse (1965), a mermaid (2001), and Fernando Botero’s smoking woman at the Cascade (2012).

Foreign Figures

The selection of foreign figures honored in Yerevan’s public spaces offers insight into Armenia’s cultural and political ties over time.

One group of prominent foreigners honored in Yerevan are Armenophiles who displayed sympathy towards Armenians in some form. The Austrian novelist Franz Werfel (2004) authored The Forty Days of Musa Dagh (1933), perhaps the best known literary work about the Armenian Genocide. The English poet Lord Byron studied Armenian with the Mekhitarists in San Lazzaro in Venice and helped compile an Armenian-English dictionary, while the Norwegian humanitarian Fridtjof Nansen is best remembred for his efforts to provide relief for Armenian genocide survivors through the “Nansen passport” and other initiatives.

Reflecting the long-standing ties with Russia, four Russians are honored in Yerevan’s streets. Interestingly, half were placed in the Soviet period, and the remainder after independence. The bust of Valery Bryusov, an early 20th century poet, remembered for his translation of medieval and modern Armenian poetry, was placed in front of the state university of languages named after him in 1966. The full body statue of Alexander Griboyedov was erected in 1974 “from the grateful Armenian people” for his role in facilitating the resettlement of 50,000 Armenians from Persia (Iran) into Russian-controlled parts of Eastern Armenia in the aftermath of the Russo-Persian War of 1828. It was vandalized in December 2019 in retaliation for the vandalism of a Garegin Nzhdeh plaque in Russia.

The bust of the Soviet Russian nuclear physicist Andrei Sakharov was erected in 2001 in the middle of the square named in his honor, replacing the Azerbaijani Bolshevik Azizbekov. Sakharov, who died in 1989, was a prominent dissident under Soviet rule. He won sympathy with Armenians during the onset of the Karabakh conflict when he spoke in favor of unification of Nagorno-Karabakh with Soviet Armenia. Nikolai Ryzhkov, the Soviet Premier who was responsible for the government’s relief and reconstruction efforts after the December 1988 earthquake, is honored with a bust. He is also the only non-Armenian to have received the country’s highest honor of National Hero, in 2008.

Yerevan also features several monuments explicitly dedicated to international friendships. These include memorials honoring relations with Estonia (1964), Arab nations (2009), France (2011), and Russia (2013). Although not officially designated as friendship monuments, several statues of foreign figures effectively serve the same purpose. Post-independence additions include busts of Argentine independence heroes José de San Martín and Manuel Belgrano, Lebanese poet Kahlil Gibran placed near Beirut Street, Chinese philosopher Confucius, Ukrainian writer Taras Shevchenko, and India’s Mahatma Gandhi. These monuments often reflect contemporary politics—Shevchenko’s statue became a gathering point for pro-Ukrainian demonstrations during Russia’s 2022 invasion, while Gandhi’s installation coincided with strengthening Armenian-Indian relations.

In a gesture of solidarity with other groups who have experienced mass atrocities, Yerevan has also established memorials commemorating the Holocaust, the Assyrian genocide, Yazidi victims of both 1915 and the 2014 Sinjar massacre, and the Nazi siege of Leningrad.

Yerevan’s evolving monument landscape reveals how public space serves as contested terrain where collective memory and political power intersect. The decisions about which figures to immortalize—or remove—reflect ongoing negotiations about national identity and historical narrative. As Armenia continues to navigate complex regional geopolitics and internal political transitions, its statues stand as silent witnesses to the country’s continuing journey of self-definition.

Footnote:

[1] A statue of the great 19th century novelist Khachatur Abovyan, celebrated as a figure of modern enlightenment, was sculpted in 1913 to be placed in Yerevan, but was not transported from a foundry in Paris at the time due to the lack of funds. The human-sized statue eventually made its way to Yerevan in 1933 and now stands near Abovyan’s family house in the Kanaker district of Yerevan.

Also see

The Revered and Overlooked Legacy of Rafayel Israelyan

Rafayel Israelyan, one of the most prolific architects of the Armenian world, left an enduring mark on Armenia’s architectural landscape with his visionary designs that included memorials, fountains, bridges, churches, government buildings, and more. Despite his remarkable contributions, his legacy is underappreciated.

Read moreYerevan’s Christian Heritage

Yerevan’s Christian heritage has usually been overshadowed because of its proximity to the Holy See of Ejmiatsin. The first accounts about churches in Yerevan are from records dating back to the Third Church Council of Dvin in 607 AD.

Read moreDiscovering Armenia: The Potential of Archeological Sites and Obstacles to Excavations

Today, there are ongoing excavations of archaeological sites throughout Armenia, including the excavation at the site of the ancient Armenian capital of Dvin. Despite the country’s huge archeological potential, specialists in the field often face numerous barriers.

Read moreThe Ambivalence of Shahumyan: Armenia’s Bolshevik Ghost

A prominent Armenian Bolshevik activist and head of the Baku Commune Stepan Shahumyan’s ghost now wanders through his native Caucasus. Armenians have largely forgotten his century-old verbal attacks on nationalism and insistence on internationalist fraternity of peoples, yet his statues remain and streets, villages and towns are named after him in Armenia and Artsakh.

Read moreThe Sculptor of Death Masks

Born in Gyumri in the late 19th century, Sergey Merkurov is considered the greatest Soviet master of death masks. He was highly sought after to take the death masks of various Soviet luminaries and leaders, as well as prominent cultural figures of the era.

Read more