Listen to the article.

As Yerevan’s skyline teems with giant cranes and its cityscape is filled with unregulated multi-story building construction and sprawling residential developments threatening heritage sites and the natural environment, the clouds of dust obscure any hope for sustainable and responsible architectural practices in the capital. Yet, amid this discouraging chaos, several independent and grassroot initiatives have emerged in recent years. Local and diasporan Armenian architects are working to educate, foster debate and critical discourse, and offer hands-on experience to rethink ways of building and introduce responsible, sustainable architectural practices.

Peer-Initiated Efforts With Impact

The Library for Architecture (LFA) has emerged as one of Yerevan’s most vibrant initiatives fostering dialogue about architectural and urban practices in the past year. Housed in a two-story garden house where Shushi-born architect Freydun Aghalyan spent his final 20 years (1926-1944), LFA has become an active educational hub serving practitioners of all ages and backgrounds. The venue—initiated by Moscow-based architect Yuri Grigoryan (co-founder of the Meganom Bureau) in collaboration with 11 Yerevan-based architecture studios, features a library and model workshop on its ground floor, with a recently expanded garage for exhibitions.

Through monthly events organized by its co-founding studios, LFA brings fresh energy to the local architectural education scene and broader cultural landscape. While the quality of programming varies between studios—and the complete carte-blanche occasionally leads to events with ethical concerns (see the review of the Total Drama festival), we believe the initiative is learning from these experiences. LFA is developing a stronger institutional framework that will help it become an exemplary peer-led model for responsible and forward-thinking contemporary discourse and practices.

Another inspiring collective undertaking is the NPATAK platform, co-founded by three young architects based in Yerevan and the diaspora. Launched in 2021 as a summer studio that paired practicing architects with students to gain experience developing conceptual proposals for clients, the platform rapidly evolved into an international festival featuring talks by leading international studios. What NPATAK brings to the local scene is an immediate engagement with world-renowned architects, fulfilling a vital need for both practitioners and especially students at the National University of Architecture and Construction of Armenia. The platform also offers international guests an immersive experience of Armenia’s history and contemporary cultural landscape, enhancing the impact of these international exchanges.

This summer, the platform partnered with Swiss-Portuguese studio BUREAU to pilot a new summer studio model—constructing a shelter structure in Armenia as part of BUREAU’s final international trilogy project. The 4th summer studio brought together local and international students, offering hands-on construction experience. Participants built a shelter using hay, wood, and concrete at the Caucasus Wildlife Refuge (CWR) area in Urtsadzor, Ararat region. While the location might have been less crucial for a temporary material and process experiment, building a permanent structure with unclear purpose in a privately protected ecocenter has limited the project’s impact. The private location not only restricts public access but also misses an opportunity to create something truly beneficial for the wider community in public spaces where such contemporary architectural interventions are most needed.

This type of livable sculpture or micro-architecture reveals its full potential when managed by art organizations—serving as a space for inspiration and creation, or as temporary housing for artists and nomadic inhabitants. The previous two shelters by BUREAU have artistic foundations and are operated by art residency organizations in Switzerland (the Antoine Shelter is installed in the 3D Sculpture Park in the Swiss Alps) and France (Thérèses Shelter sits on land where the Bermuda artistic community conducts its artistic and environmental activities). Following the summer studio, the NPATAK festival took place in early September, featuring a rich program of talks and events. Alongside this, a Learning by Stone design workshop brought together students from HEAD Geneve, NUACA, and TUMO studios. This material-focused, craft-oriented weeklong program culminated in a presentation at the festival’s closing event. NPATAK emerged as a vital meeting point and platform for knowledge production and exchange, forging new connections between professionals across diverse backgrounds and generations.

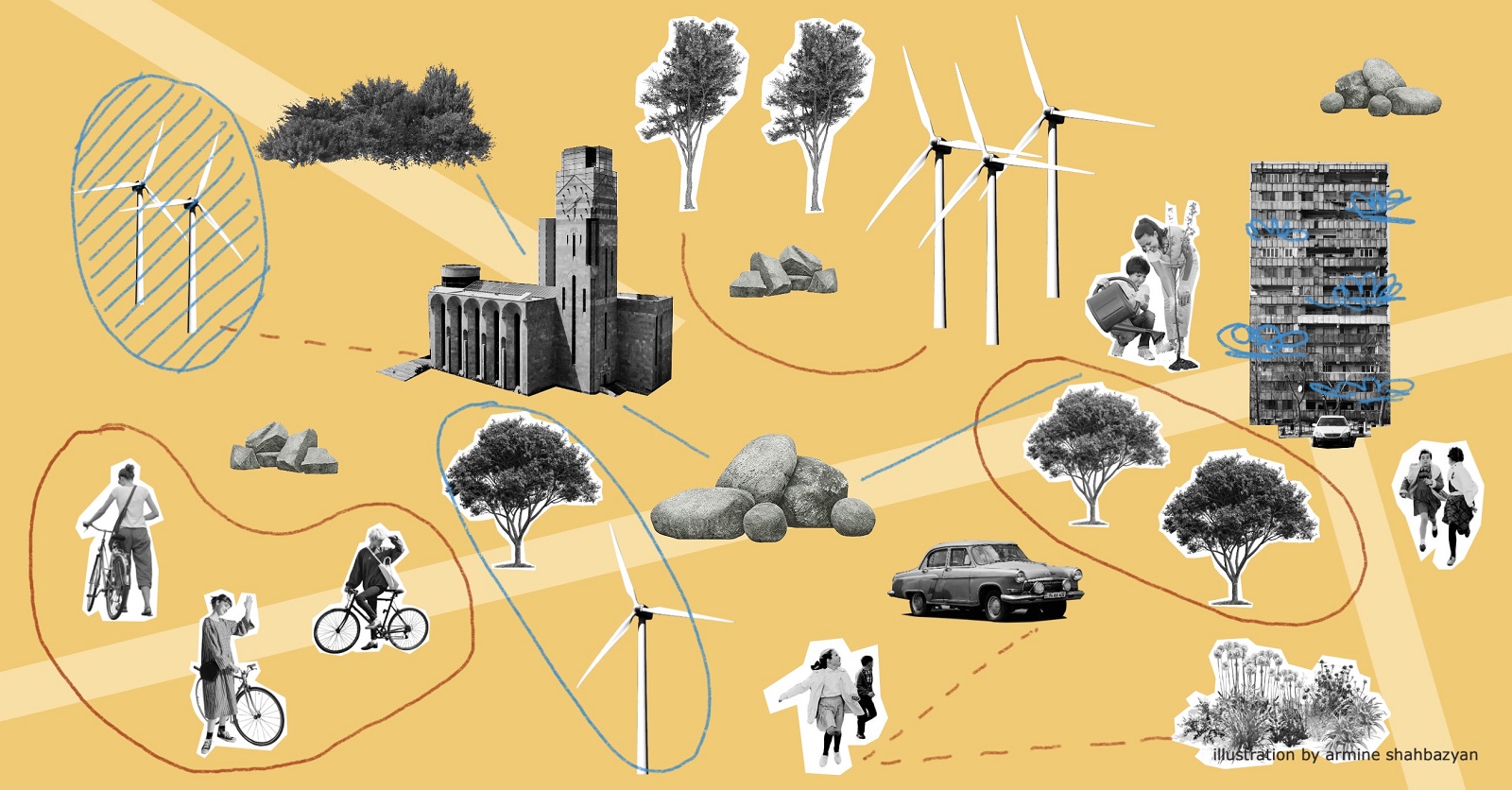

In the Urtsadzor and wider Vedi River Valley region, a parallel project delves deeper into the local context through an international educational-planning initiative. Led by architect Guillaume Othenin-Girard, assistant professor at the University of Hong Kong, and working with archaeologists from the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography of the National Academy of Armenia, this interdisciplinary project broadens architectural practice by developing a climate-responsive strategy for the valley. Over the past two years, the team has worked with various local stakeholders—including community members, municipal authorities, and specialists—to identify future scenarios and sustainable building methods. Through this process, they have developed various “proto-projects” or “seed projects” that highlight the valley’s heritage resources and demonstrate ways to bring these elements into harmony.

One of these proto-projects is an archaeological field laboratory, inspired by the design of “A Room for Archaeologists and Kids” at the Museum of Pachacamac in Peru, which Guillaume Othein-Girard directed in 2018-2019. The Swiss-born architect conducted in-depth research on traditional Armenian architectural forms and techniques, particularly the “Glkhatun” and the “Hazarashen” roof structure. This research led him to design a pilot lab structure with his architecture students from the University of Hong Kong. Their field research produced a collection of hazarashen drawings and simulations, forming the basis for a future handbook on developing the Armenian Glkhatun’s thermal and environmental potential.

Through Othenin-Girard’s locally-rooted architectural approach, combined with international apprentice architects and local community engagement, this collaborative project brings fresh perspectives and innovative methods to Armenia—creating potential for lasting impact. The dynamic interaction between local and international practitioners across disciplines and generations shows Armenia’s potential as a site for innovative, forward-thinking design practices that blend traditional building methods and material culture with global sustainable architecture approaches.

Sustainability at the Core of the Oshakan Project’s First Summer School

London-based architect and professor Aram Mooradian and Yerevan-based Harvard Graduate School of Design graduate Shant Charoian launched an architecture summer school for sustainable construction and heritage in Oshakan in July. Through a partnership with London’s Architecture Association (AA) Visiting School program, the Oshakan Project welcomed 18 local and international students for a two-week surveying program from July 6 to 21.

The summer school marks Mooradian’s first practical project in Armenia, extending his material-focused approach from his community work in London’s Hackney district:

“The aim is to expose students at a young age to the notion that buildings aren’t just facades, that they are complex amalgamations of materials that exist in time, and that those materials come from somewhere and go somewhere. If we are going to tackle the huge waste and carbon consumption that the construction industry is responsible for, then it is this kind of material-focused perception of space that I think is important for creating sustainable building culture. Armenia is developing at pace, and I wanted to test some of the concepts that I’ve developed over the years in my teaching by putting them into practice in a longer-term summer school. One key concept of sustainable construction is ‘use what you have’. I think when we start to adapt existing buildings we change their meanings. That’s where the heritage angle comes into play—we have to be aware of the meanings we are changing when we retrofit buildings. Armenia, with its depth of history and rapid development, is the perfect setting for this.”

Aleppo-born architect Shant Charoian’s vision for the summer school is driven by his passion for researching local contexts and viewing heritage through fresh perspectives: “My goal is to have the current generation of architects in Armenia realize the beauty of our country’s history, and see how much potential lies in learning from our heritage. Sadly, we are constantly trying to imitate other countries’ construction methods and styles. I think it is about time we start to embrace our country’s history. What does studying heritage have to do with contemporary architecture?”

The location for launching the summer school was chosen quickly. The picturesque village of Oshakan, situated 26 km northwest of Yerevan, offered the diversity needed for first-time students visiting Armenia: the beautiful Kasakh River gorge with its cave churches, archaeological sites from Urartian and Seljuk periods, historical layers from Medieval to Modern eras, and the yet-to-be revitalized pilgrimage site of the tomb of Mesrop Mashtots: “When Aram and I were looking for how/where to start the summer school, we knew we wanted to embed it within a community,” explains Shant. “After a few trips to Oshakan, especially after meeting with the women who run the Oshakan Culture House, we knew that this was the correct community to work with. They were so open and excited at the prospect of our summer school, which made it seem even more fitting, that there was a local initiative on our side.”

The Oshakan Project offered hands-on experience to a new generation of international and local architects learning from Armenia’s context. The pedagogy focused on key principles: surveying the existing built and natural environment and material culture, building relationships with the local community, introducing sustainable ways of building, promoting adaptive reuse of heritage and circular economy. Such a contextualized approach not only develops students’ sensitivity to local knowledge, resources, and practices but also allows them to imagine sustainable construction techniques rooted in place. The first year was dedicated to mapping the local area and working with the community to identify opportunities for a public structure to be designed in future summer schools. As Aram explains, “It takes time to build trust with a community, and it is important to us that any future interventions reflect the community’s own desires, rather than being parachuted in. For architecture to survive, it needs to be embedded. Our aim was to teach students the surveying skills needed to embed a project in place and its community.”

The summer school took place across Aragatsotn region, immersing 18 participants (15 international, three local) in its diverse natural and cultural landscapes and communities. Participants stayed at the Byurakan Observatory guest house, while community workshops were held at the House of Culture in Oshakan, with research and surveying conducted throughout the village. Through a series of talks and field trips to historical sites in the region and Yerevan, invited practitioners helped students gain a deeper understanding of local context and contemporary heritage practices. On July 21, students presented their work at a public event. The floor and walls of the House of Culture—a well-preserved building designed by Gevorg Tamanyan in the late 1950s—exhibited maps, drawings, imprints, archives, photographs, found objects, artifacts, and even a life-sized drawing of a stork’s nest. One participant experimented with extracting pigments from stones found in Oshakan’s historical Didikond district to create paint.

Drawing from surveying materials and local knowledge collected in the first year, the Oshakan summer school shows promise in unearthing new approaches to sustainable architecture in Armenia. Its location in a village—at Mashtot’s resting place—makes the initiative both deeply rooted and forward-looking. Could Oshakan pioneer a new language of sustainable architecture? In an era where grand architectural gestures and monumental structures take precedence over responsive and regenerative design, a new generation of environmentally and politically conscious architects stands ready to lead. They are positioned to shift toward culturally, socially, and ecologically responsible practices that address climate change, resource scarcity, and the need for an inclusive vision.

Through its humble beginnings, the Oshakan Project offers a promising alternative to Armenia’s educational landscape. The co-founders aim to integrate diverse expertise—artists, craftsmen, designers and researchers. If successful, Oshakan will reflect the 2025 Venice Architecture Biennale’s “Intelligens” theme, demonstrating how collective intelligence and local ingenuity can guide architecture toward an ecological, ethical, collective and aesthetic future.

Also see

Rethinking Monument Preservation in Armenia

Armenia is developing policies to inventory, preserve, restore and promote historical monuments, recognizing their economic and cultural value. While progress aligns with sustainable development goals, significant challenges in preservation and management persist.

Read moreThe Revered and Overlooked Legacy of Rafayel Israelyan

Rafayel Israelyan, one of the most prolific architects of the Armenian world, left an enduring mark on Armenia’s architectural landscape with his visionary designs that included memorials, fountains, bridges, churches, government buildings, and more. Despite his remarkable contributions, his legacy is underappreciated.

Read moreFrom Heritage to Hype

An op-ed calling for a collective reflection on the potential pitfalls of Armenia’s burgeoning arts and cultural festival scene falling into the trap of “artwashing” and sidelining the much needed potential of cultural festivals to facilitate community bonding and critical engagement with the past.

Read moreModern Challenges of a Capital City, Part 1: Urban Planning

The first in a series of articles about the challenges facing Armenia’s capital city, Yerevan, examines the issues of urban planning and development.

Read moreOn Urbanization in Armenia: From “City-Building” to Urban Planning

Development projects are popping up haphazardly in Armenia. Many of them pursued for short-term economic goal under the pretext of development. Without a holistic vision for growth in the country, consequences of decisions taken today will be irreversible for generations to come.

Read moreZones of Entrapment: Yerevan’s 2800th Anniversary Park and the Tyranny of Taste-Fullness

In the context of autocratic, oligarchic or committedly neo-liberal regimes which continually propagate a coercive and incarcerating model of urban planning, the multiplication of such spaces as the 2800th Anniversary Park of Yerevan is organic, writes Vigen Galstyan.

Read more

New section on

EVN Report

Keep an eye out for updates!