Armenia’s security situation remains precarious, as Azerbaijan has exponentially increased its use of interstate conflict mechanisms, undertaking both large-scale invasions as well as incrementally utilizing hybrid warfare to justify violations of the ceasefire. Armenia has resorted to intense diplomatic initiatives, both publicly and through backchannels, to bring international pressure upon Azerbaijan. Lacking military deterrence capabilities, Armenia has relied on the diplomatization of its security by coordinating diplomatic pressure with the United States, the European Union, and France to deter Azerbaijan from further interstate militarized activities. The relative marginalization of Russia from the process, and the inability of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) to serve as an agent of security in addressing Armenia’s security dilemma, has altered Armenia’s understanding of Russia as a security ally. For all means and purposes, the Russian-led security architecture in the South Caucasus has collapsed, and Russia is no longer qualified as Armenia’s security guarantor.

Armenia’s Security Context

The security context in September 2022 was primarily hinged, at the outset, on developments specific to the negotiations initiated by the European Union between Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan and President Ilham Aliyev. The U.S. presented a positive assessment of these developments, while Russia noted suspicion of the EU-led negotiations. The outcome of the meetings remained incommensurate with the objectives of either side, as Armenia noted the difficult nature of the negotiations, while Azerbaijan reverted to its posture of coercive diplomacy. The latter became apparent in the pattern of behavior undertaken by Azerbaijan’s Ministry of Defense. On September 2, Azerbaijani forces initiated hostilities against Armenian targets, while undertaking combat training in Lachin. From September 3, application of gray zone tactics escalated with continuous accusations against Armenia for violating the ceasefire, which Yerevan adamantly denied. These accusations continued on September 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, and 12, culminating in Azerbaijan’s large-scale invasion on September 13. Collectively, the security context continued to deteriorate after the Brussels negotiations, as Azerbaijan, on a daily basis, intensified gray zone tactics leading to the September 13 operation.

The scale and scope of Azerbaijan’s offensive was expansive, covering over 30 population centers, with the bulk of concentration on Sotk, Jermuk, Goris, and Ishkanasar, culminating in positional advancements towards Nerkin Hand, Verin Shorzha, and Sotk. The strategic objective of Azerbaijan’s operation was the absorption of Jermuk as part of an expansive buffer zone within Armenia proper, considering the scope of its operational drive, while simultaneously taking control of strategic heights to reinforce the buffer zone. The result was Azerbaijani forces advancing 1.5 kilometers in the directions of Nerkin Hand and Verin Shorzha, half a kilometer in the direction of Ishkanasar, and approximately 7 kilometers towards Jermuk.

The rapid deterioration of Armenia’s security architecture resulted in Yerevan undertaking two approaches: flurry of diplomatic activity with international partners and formally appealing to the CSTO to fulfill its security obligations. In a matter of hours, Prime Minister Pashinyan spoke with Russian President Vladimir Putin, French President Emmanuel Macron, US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken, President of European Council Charles Michel, and President of Iran Ebrahim Rais. Foreign Minister Mirzoyan, at the same time, communicated with US Assistant Secretary of State for European and Eurasian Affairs Karen Donfried, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, Canadian Foreign Minister Mélanie Joly, and Foreign Minister of France Catherine Colonna. Simultaneously, an extraordinary session of the CSTO Collective Security Council was called, with the CSTO determining to send a fact-finding mission, but refraining from either committing force or providing Armenia with diplomatic support. Amid the deterioration of Armenia’s security situation, along with both Russia’s and CSTO’s refusal to provide physical security or impose a ceasefire, Yerevan relied heavily on the United States and France to apply diplomatic pressure on Baku. A ceasefire was reached in the evening of September 14 primarily through the initiative of the United States.

As the security situation remained perilous, with no substantive guarantees that the ceasefire will hold, Yerevan continued to rely on diplomatic channels to reinforce the ceasefire, with PM Pashinyan again speaking with U.S. Secretary of State Blinken, French President Macron, and Russian President Putin. This was supplemented by continued communication between Armenia’s Ministry of Defense and America’s Department of Defense, as Defense Minister Suren Papikyan held conversations with U.S. Deputy Secretary for Defense for Policy Affairs Colin Kahl. Within this broader context, as the lack of physical security guarantees became slowly filled with diplomatic support, two important developments contributed to the relative strengthening of Armenia’s security situation: the visit of U.S. Speaker of the House of Representatives Nancy Pelosi and France taking Azerbaijan’s aggression to the UN Security Council.

Collectively, with the deterioration of Armenia’s physical security, along with Russia’s and the CSTO’s tacit relinquishing of its treaty obligations, the entirety of Armenia’s security architecture has become hinged on diplomatic coordination with the United States and France. Qualified as an instrumental shift in U.S. regional policy, Speaker Pelosi’s visit displayed a robust vote of confidence for Armenia’s democracy and security, while thoroughly condemning Azerbaijan for its invasion into Armenia proper. This posture was further reinforced by the U.S. Embassy in Armenia as well as by the U.S. State Department. On the other side of the diplomatic pincer move, France brought Armenia’s security situation to the UN Security Council, with a general consensus that remained favorable to Armenia, as India, Norway, Ireland, France, and the United States displayed support for Armenia, while Russia and China displayed neutrality.

About the author

Dr. Nerses Kopalyan is an Associate Professor-in-Residence of Political Science at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. His fields of specialization include international security, geopolitics, political theory, and philosophy of science. He has conducted extensive research on polarity, superpower relations, and security studies. He is the author of “World Political Systems After Polarity” (Routledge, 2017), the co-author of “Sex, Power, and Politics” (Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), and co-author of “Latinos in Nevada: A Political, Social, and Economic Profile” (2021, Nevada University Press). His current research and academic publication concentrate on geopolitical and great power relations within Eurasia, with specific emphasis on democratic breakthroughs within authoritarian orbits. He has conducted extensive field work in Armenia on the country’s security architecture and its democratization process. He has authored several policy papers for the Government of Armenia and served as voluntary advisor to various state institutions. Dr. Kopalyan is also a regular contributor to EVN Report.

September Insights

Video interview

EVN Report’s Editor-in-Chief Maria Titizian speaks with Dr. Nerses Kopalyan, author of a new monthly series called EVN Security Report. The security briefing provides data-driven, in-depth analysis of Armenia’s precarious security situation following the 2020 Artsakh War.

The diplomatization of Armenia’s security dilemma was reinforced with PM Pashinyan’s meeting with Secretary of State Blinken at the 77th session of the UN General Assembly, which was followed up by meetings with Charles Michel, UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres, and NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg. The instrumentalization of diplomatic coalition-building continued with National Security Council Secretary Armen Grigoryan visiting Washington on September 26, while PM Pashinyan flew to France for an official visit with President Macron. Armenia’s endeavor of building consensus around Azerbaijan’s aggression was reaffirmed with France aligning its posture with that of the United States: Azerbaijan remains the aggressor and must return its forces to its initial positions, for its behavior constitutes a violation of Armenia’s sovereignty. This was followed with a visit by Armenia’s Minister of Defense, Suren Papikyan, to France on September 27, where French Defense Minister Sébastien Lecornu confirmed that a French military delegation will visit Armenia to study the security situation.

Strategic Evaluation

Armenia’s Russian-led security architecture has collapsed. Russia remains unable to fulfill its security obligations toward Armenia, whether within the scope of the 1997 bilateral treaty between the two states or Armenia’s membership in the Russian-led CSTO security arrangement. With Azerbaijan’s continuous incursion since the November 9, 2020 trilateral ceasefire, and compounded by the current invasion into Armenia proper, Russia’s position has become quite straightforward: in matters specific to interstate militarized disputes initiated by Azerbaijan, Russia’s security obligations to Armenia are not applicable. In essence, Russia has abdicated its responsibility as Armenia’s security guarantor. The problems facing Armenia remain three-fold:

- Considering the dependency structure of Armenia’s security architecture for the last three decades, the realignment of Armenia’s security doctrine requires a transition from dependency on Russia to establishing deterrence capabilities with strategic partners.

- Arms procurement has been a problem since the 2020 Artsakh War, as Armenia finds itself in a predicament: Russia has not sold Armenia weapons in the last two years, while Armenia struggles to procure weapons from pertinent countries due to its membership in the CSTO. The outcome has been an exponential increase in the power disparity, as Azerbaijan has continued to arm itself, while Armenia has relied on Russia, to no avail, in the hopes that Russia will meet its obligations.

- The collapse of the Russian-led security architecture has diminished Armenia’s capacity to provide for its own physical security, requiring Yerevan to engage in the diplomatization of its security until the issues of deterrence and arms procurement are resolved.

Compounding these predicaments is the continuation and enhancement of Azerbaijan’s hybrid warfare tactics, as Azerbaijan transitions from gray zone tactics to actual militarized operations, thus capitalizing on both the decay of Armenia’s security architecture as well as Armenia’s inability to establish a manageable power parity. Azerbaijan’s objectives are twofold: capitalizing on the decline of Russia as regional hegemon and coercing Armenia into concessions that were not achieved during the 2020 Artsakh War. The former is an exercise in crude opportunism, while the latter is an extension of a well-developed grand strategy. At the moment, however, the two objectives have aligned. To achieve these objectives, Azerbaijan is utilizing three main methods: salami slicing, borderization, and policy of reciprocity with Russia.

Salami Slicing

An important method in Baku’s grand strategy is the technique of salami tactics, which are repetitive, limited, low-cost fait accomplis designed to expand influence. Azerbaijan uses salami slicing to engage in controlled destabilization, a process in which it manufactures instability to undertake slicing tactics, then acquiesces to a ceasefire as an act of stabilization. By leveraging its own acts of localized violence to achieve prefered outcomes, it acts as both aggressor and peacemaker. This capacity for controlled destabilization reinforces the incremental process that serves the broader strategy of continuous salami slicing. An underlying mechanism of instituting salami slicing operations is the tactical use of the claim of “provocation,” which allows the conditions to both manufacture instability as well as claim self-defense in face of one’s own artificially constructed crisis. This remains consistent with all deep trend analysis which demonstrate an observable pattern of “provocations” claimed by Azerbaijan prior to its initiation of interstate militarized operations.

Borderization

With the technique of borderization, Azerbaijan is using the concept of “elastic geography” to justify its policy of creeping borderization, as it allows the issue of demarcation to function as an instrument of leverage. By claiming ambiguity, and reinforcing this ambiguity through gray zone tactics, it is incorporating salami slicing techniques with creeping borderization. In essence, if the borders between two states are ambiguous, how can accusations of an invasion be substantiated, since there is ambiguity in what constitutes territorial sovereignty? By instrumentalizing an elastic conceptualization of geography, Azerbaijan is slicing territories off of Armenia proper, and relying on borderization to create new facts on the ground. This allows Azerbaijan to fluctuate on the use-of-force spectrum, ranging from use of small arms for provocations to large-scale invasions and mass shelling of civilian targets. In the realm of coercive diplomacy, the aim of borderization is political acquiescence. In this context, it is designed to initiate political inertia, while reinforcing the new facts on the ground, thus allowing Azerbaijan to attempt to dominate and force submission through deception, violence, and insecurity.

Policy of Reciprocity with Russia

A well-established policy of reciprocity with Russia has been articulated by Baku that allows Azerbaijan certain leeway in its aggression towards Armenia, with the parameters being defined by mutual reciprocation of gains for Russia. Azerbaijan cemented these arrangements by signing the Moscow Declaration on February 24, prior to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The 43-point arrangement covers everything from cooperation in regional and military policy to banking and energy, thus entrenching the mutual adjustment of interests by both states. Further, in the realm of energy cooperation, Russia’s Lukoil purchased a 25% stake in the Shah Deniz project, thus becoming an integral player in the Shallow Water Absheron Peninsula (SWAP) exploration project in the Azerbaijani sector of the Caspian Sea. Just as importantly, Russia and Azerbaijan are signatories, along with Iran, on the development of the North-South Transport Corridor, designed to enhance transportation and transit issues through Azerbaijan and into Russia.

These strategic and reciprocal alignment of interests are strongly correlated with Russia’s generally muted response to Azerbaijan’s violations of Armenia’s sovereignty. Contextually, Russia has not only reinforced both-sideism, as opposed to supporting its ally, but has in fact utilized Baku’s talking points and justifications for interstate militarized activities. By, for example, reinforcing the narrative of border demarcations as justifications for Azerbaijan’s behavior, Russia is speaking in Azerbaijan’s language, as opposed to that of its ally. Thus, whereas Armenia’s appeals to Russia are based on violations of its sovereign territory, Russia’s response is aligned with the Azerbaijani argument: sovereignty has not been violated due to unclear borders. The Azerbaijani talking point was also noted within the CSTO: violation of borders cannot be a subject of discussion if borders are not demarcated.

Collectively, salami slicing and borderization enhances Azerbaijan’s capacity for coercive diplomacy, while also creating new facts on the ground that increase its levers of pressure on Armenia. Supplementing this security dilemma is Russia’s acquiescence to Azerbaijan’s narrow objectives, as Russia’s negligence in fulfilling its security obligations to Armenia insulates Azerbaijan from the pressures of the regional hegemon. To this end, Azerbaijan enjoys the unequivocal support of Turkey and the tacit consent of Russia, thus allowing Baku to maximize its already maximalist posturing against Armenia. Based on such security configurations, Armenia’s only alternative remains the utilization of diplomacy as an act of temporary reprieve, while accepting the fact that it has been forsaken by its only security guarantor. From Yerevan’s perspective, this necessitates a tilt towards the United States and France, with the hopes that the former will provide sufficient political capital, while the latter may serve as a potential security partner (not guarantor) and supplier of arms.

System’s Analysis

As Armenia’s Russian-led security architecture has collapsed, and as power configurations in the South Caucasus have shifted, larger systemic and structural factors have mitigated both developments. At the system’s level, Russia’s hegemony has declined, Turkey’s involvement has been indirect, Iran’s posturing hinged on red lines, and U.S. involvement defined by a new power vacuum due to Russia’s decline. While France has not precisely become a regional actor, it has interjected itself through its diplomatic support of Armenia, filling the large void left by Russia’s negligence. The fundamental systemic factors that explain Armenia’s security conditions, however, are primarily hinged on two factors: Russia’s abdication of its role as guarantor and America’s shift to fill the power vacuum.

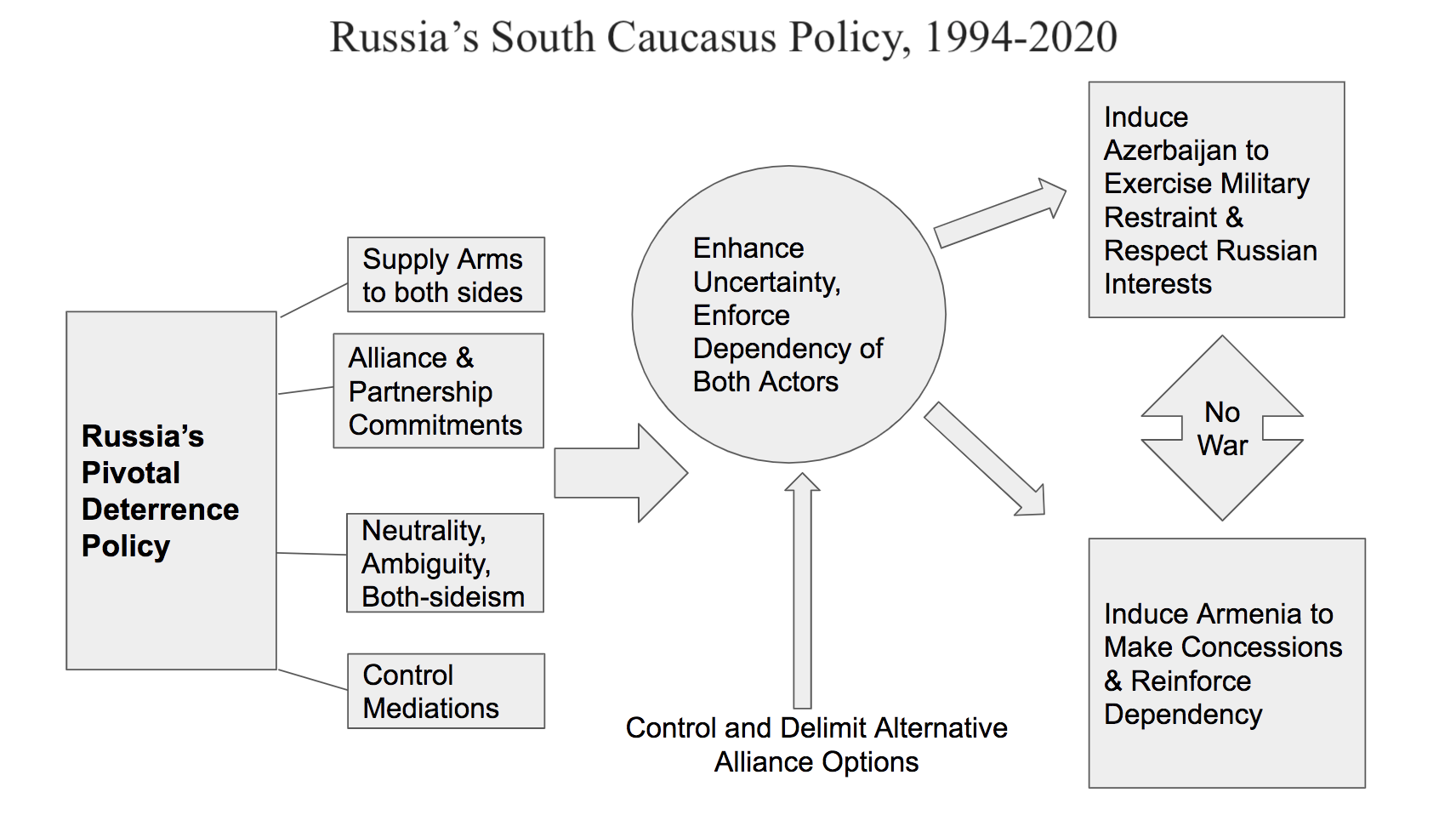

While the Ukraine war is the exogenous factor producing systemic repercussions in the South Caucasus, the splintering of Russia’s security policy for the region may be best understood by observing the collapse of its “pivotal deterrence” policy. Borrowing from Timothy Crawford’s conceptual model, this precept holds that a regional power does not take sides between two conflicting states, but rather has an interest in deterring war. Thus, the regional power pivots between the warring states to deter either actor from initiating hostilities. Russia’s pivotal deterrence was defined by its power to affect potential military outcomes, leading both states to fear a pivot against them. Pivoting, as a strategic act of deterrence, exerted leverage against both actors, for Russia would either maintain neutrality or support one of the sides. The ambiguity and uncertainty that came with Russia’s posture of neutrality, and the unpredictability of a pivot should either side misbehave, deterred the probability of full scale war.

*This graph borrows heavily from Laurence Broers’ visual rendering of pivotal deterrence theory in the South Caucasus.

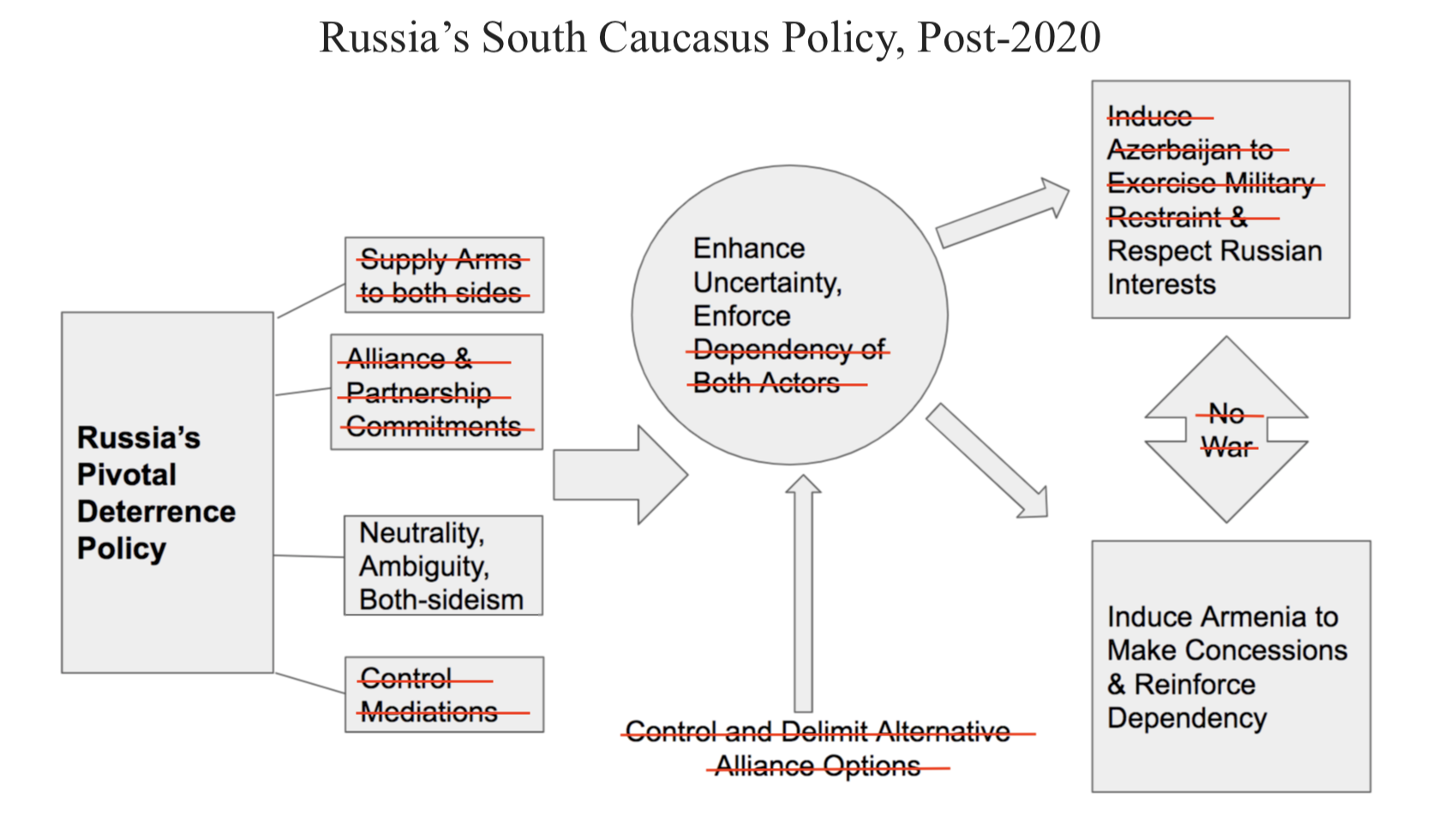

Azerbaijan’s launch of the 2020 Artsakh War eroded Russia’s pivotal deterrence policy, while post-war military activities by Azerbaijan, followed by Russia’s setbacks in Ukraine, led to the disintegration of this regional policy. Unable to deter Azerbaijan, and unwilling to pivot towards Armenia, the collapse of Russia’s pivotal deterrence policy led to the collapse of Armenia’s Russia-dependent security architecture.

As the graphing of the collapse displays, Russia’s lack of ability to arm either side, meet alliance obligations, or control mediations contributed to its decline as a regional hegemon. Azerbaijan had increased its military expenditure independent of Russia, while Russia remained unable to fulfill its obligations of sufficiently arming Armenia. Its capacity for neutrality and ambiguity, to this end, had become negated, and while it did enhance uncertainty, Russia no longer had robust leverage to deter Baku. Further, Russia’s ability to control or limit “alternative alliance options” had been degraded, as Azerbaijan had invited Turkey into the South Caucasus. As such, the inability to pivotally deter Baku led to the collapse of Armenia’s security architecture, leading Armenia to also consider alternative alliance options. The outcome of Russia’s regional decline, in this context, and the collapse of its pivotal deterrence policy, is the increased regional presence of the United States, along with that of France as an “alternative alliance option” for Armenia.

America’s pivotal shift in the South Caucasus is precisely designed to replace Russia’s failed pivotal deterrence policy, as the U.S. seeks to fill the void as peacemaker, but do so by tacitly implementing the Biden Doctrine. Conceptually, the U.S. seeks to curtail Azerbaijan’s aggressive behavior, thus enhancing Armenia’s security and the survival of its democracy, while at the same time diminishing Russia’s leverage in the region by dislodging Armenia from Russia’s orbit. The U.S. is seeking to carve out a democratic sphere of influence in the region, as the democratic dyads of Armenia and Georgia may serve as important anchors in amplifying U.S., and by extension, European interests in the region. The positions taken by the United States, France, United Kingdom, and much of Europe, in this context, are an exercise in pivotal deterrence, but primarily through the instrumentalization of diplomacy. In essence, the U.S. is seeking to deter Baku’s aggression by signaling a pivot towards Armenia, a shift from its three-decades’ long policy of neutrality. The objective is not to embolden Armenia, or to choose sides in the broader scheme of things, but rather, to deter Azerbaijan from expanding the theater of war. To this end, the systemic implications for Armenia’s security architecture indicate a growing diplomatic deterrence structure led by the U.S. to replace Russia’s diminished hard power deterrence structure.

Functional Strategy

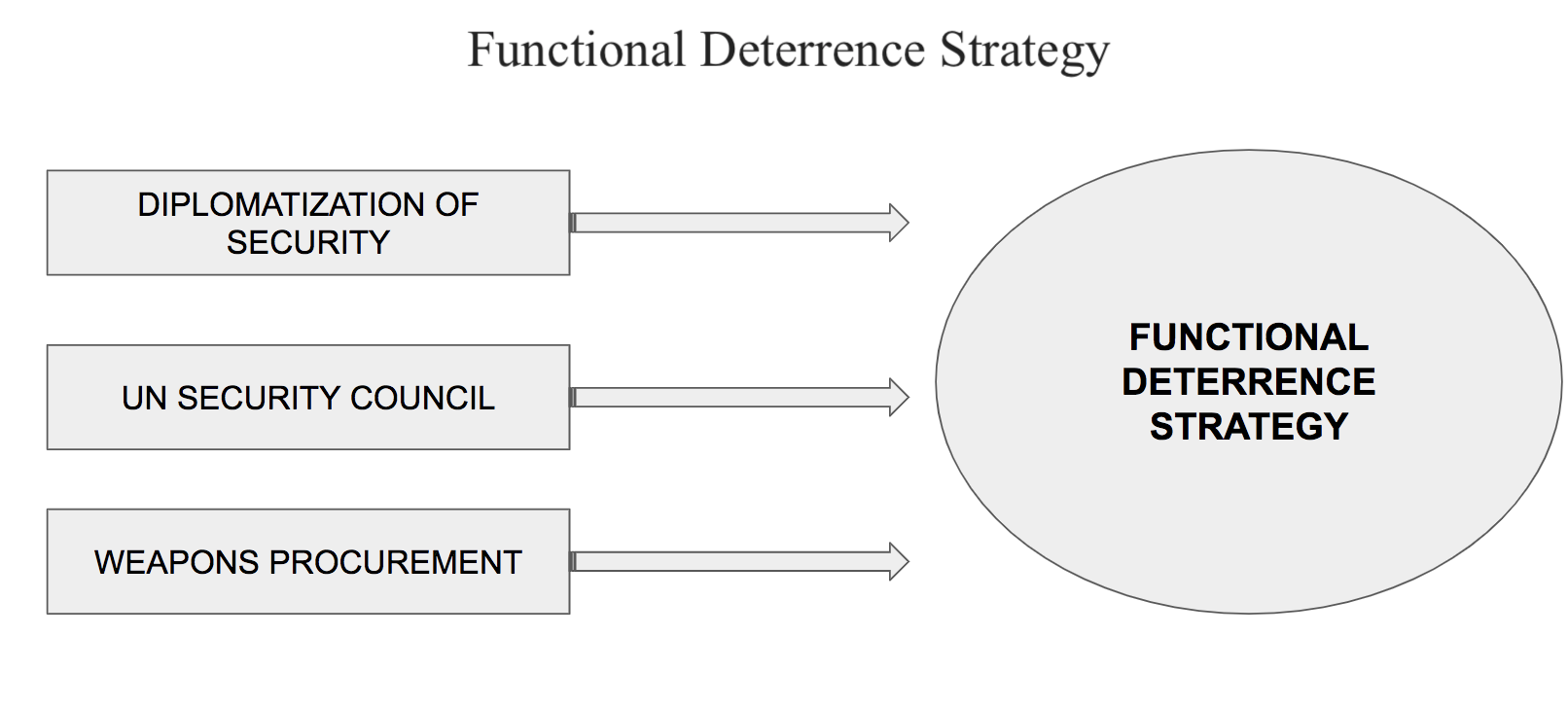

In the face of the precarious security situation facing Armenia, Yerevan’s functional strategy remains reliant on two main approaches: diplomatization of its security and procurement of arms independent of Russia. Armenia’s fundamental and underlying objective in its functional strategy is to develop some semblance of a deterrence structure. At this point, this nascent attempt at developing such a structure entails a system’s level reliance on the United States, robust diplomatic support from France, and arms procurements from India and other partners. Convinced that neither Russia nor the Russian-led CSTO has any intentions of deterring Baku’s behavior, Yerevan has removed Russia from its functional deterrence strategy. This, of course, does not entail a decoupling of relations, but rather, noting Russia’s problems in Ukraine, and conceding its severe decline in influence in the South Caucasus, Armenia is restructuring its security architecture.

Armenia’s attainment of a functional deterrence strategy appears to rely on three pillars: continued diplomatization of its security, seeking international observers and action from the UN Security Council, and procurement of arms to mitigate the power disparity.

With the active involvement of the United States, European Union, and France, Armenia has wedged its diplomatic deterrence strategy on relying upon these actors to curtail Azerbaijan from undertaking another large-scale invasion. This diplomatization of its security is supplemented by Armenia appealing to international security mechanisms to further deter Baku’s aggression, including active engagement within the UN Security Council as well as calling for an international observer mission. Specifically, considering the consistency in the positions of the U.S., France, and the U.K. on the need for Azerbaijan to retreat its forces and leave Armenia proper, a UN Security Council resolution on this matter remains an instrumental objective for Yerevan. Finally, the long-term process of enhancing Armenia’s hard power capabilities is being initiated through consultations with the French Ministry of Defense as well as a sizable arms procurement from India.