Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

There are three key components to each state’s citizenship policy.[2]

A․ By Soil or by Blood

There are two basic principles for granting citizenship: jus sanguinis (Latin for “right of blood”) and jus soli (Latin for “right of soil”). The most widespread is the first, which stipulates that, upon birth, a child is granted the citizenship that their parent (or parents) hold. This principle guides most of the countries in Europe and the Eastern Hemisphere more generally, including Armenia. The second stipulates that all those born within the territory of a given country are recognized as its citizens. It is more common in the Western Hemisphere, where a history of colonialism and slavery led to migration playing a significant role in the formation and development of the state.

However, it must be taken into account that these two principles are neither absolute nor separate; as a rule, states that have adopted one of the principles can apply the elements of the other. There are also many cases when the state defines additional conditions related to the dominant principle.

B․ Exclusive Or Inclusive to Dual Citizenship

Citizenship is defined as the basis of the mutual rights and obligations of an individual and a state. It used to be taken for granted that such arrangements were of an exclusive nature. In other words, the possibility of similar relations with another state for the same individual was excluded or not legally recognized. However, the increase in global migration has created practical problems for all those who are citizens of one country but have settled in another. Many countries today silently acknowledge that their citizens may also be citizens of another country, even if such dual citizenship is officially prohibited. Although the number of countries preferring the inclusive approach (i.e. welcoming dual citizenship or, more precisely, multi-citizenship) is still relatively small, the trend is for countries to move in that direction rather than the other way around. The reasons are different for each specific case. On the whole, however, it can be attributed, on the one hand, to the weakening of perceptions of nation-states and the absolute loyalty of their citizens to them and, on the other hand, to the desire of states to have more flexible tools in the global competition for human capital.

As with the principles of jus sanguinis vs. jus soli, a state’s approach can still combine elements of both exclusivity and inclusivity. Exceptions and special arrangements abound. For example, Germany, which has adopted an exclusionary approach, requires that any individual obtaining German citizenship (including those who were originally Armenian citizens) renounce their current citizenship as a precondition. However, Germany does allow its citizens to acquire the citizenship of another EU member state (which Armenia is not) without renouncing their German citizenship. A similar exclusionary approach existed in Russia until 2020, though certain exceptions were extended to citizens of Turkmenistan and Tajikistan, which had signed special agreements with Russia. Georgia also famously took an exclusive approach; obtaining the citizenship of another country was grounds for losing Georgian citizenship. However, through a recent constitutional amendment in 2020, a person cannot be deprived of Georgian citizenship on these grounds, which means accepting that a citizen of Georgia can also be a citizen of another state.

C. Conditions For Naturalization

The final key component is naturalization. States can set a diverse combination of conditions under which they will accept a foreign citizen as one of their own. They often consider:

- duration and grounds for legal residence in the country,

- origin of the applicant (in the case of Israel, religious affiliation is also taken into account),

- knowledge (language, history, constitution, etc.),

- behavior (criminal record, moral character, etc.),

- existing ties with the state (marriage or other family ties with a citizen of the state, financial investments, etc.).

These three key components form the basis of a state’s citizenship policy. They are combined to realize the priorities of a state, and can change as those priorities change. In the Gulf states, where the economy is heavily dependent on immigrant labor, it is virtually impossible to become a naturalized citizen, even after legally living and working in those countries for decades. Although, here too, there has been some limited liberalization in recent years in Qatar and the United Arab Emirates.

Armenia’s Citizenship Policy

As is the case for all newly-independent states, there was a need to establish who the Republic of Armenia would actually represent. Despite differing perceptions and definitions of citizenship, membership to the political community is accepted as the most widespread component.[3] Therefore, it is no accident that the issues of citizenship are mentioned in the fundamental documents of the Republic of Armenia. An entire article was devoted to citizenship in the Declaration of Independence adopted by the Supreme Council (the predecessor to the National Assembly) on August 23, 1990. Article 4 declares that “Citizenship of the Republic of Armenia is defined for all [formerly Soviet] citizens residing in the territory of the Republic of Armenia,” and also adds “Armenians abroad have the right to citizenship of the Republic of Armenia.” In other words, the declaration of independence established the right of not only the people of Armenia, but also Armenians around the world, to have membership in the newly-created political community.

The 1995 Constitution clarified in the first article of the chapter on Basic Rights and Freedoms of the Human Being and the Citizen, that “Armenians by national origin shall acquire citizenship of the Republic of Armenia through a simplified procedure prescribed by law,” preparing the ground for those of Armenian descent to obtain citizenship through a simplified procedure, to be adopted a few months later. However, the same article of the Constitution also took an exclusionary approach: “A citizen of the Republic of Armenia cannot simultaneously be a citizen of another State.” This implied that, although Armenians who did not reside in Armenia during the period of independence could obtain Armenian citizenship under certain conditions, they would have to renounce their former citizenship and political allegiance to other states to do so. Those terms were also detailed in the Law on Citizenship, adopted in November 1995. The granting of Armenian citizenship was based on a multi-layered approach, primarily granting citizenship to those from other USSR republics who were in Armenia in case of applying for such status. Naturally, the overwhelming majority in this case were ethnic Armenians who had been deported or fled from Azerbaijan. However, there was also an influx to Armenia from neighboring Georgia, as well as from other former Soviet republics.

In addition, citizenship was extended to persons regardless of ethnic background who resided in Armenia during the creation of the Third Republic but then left the country afterward, as long as they did not assume another citizenship, i․e․ political loyalty to another state. Additionally, those Armenians who were citizens of Soviet Armenia but left prior to the independence referendum could apply to become citizens of Armenia as long as they did not have citizenship of another country. A simplified procedure for obtaining Armenian citizenship was also established for all those of Armenian origin who could hold a conversation in Armenian, were familiar with the Constitution and had already settled in Armenia. By “simplified procedure”, the main exception provided to this group was that they did not need to have resided in Armenia for three years.

Clearly, in all three categories, the actual circle of people eligible for citizenship was quite narrow; the exclusionary conditions for obtaining citizenship, in general, set a fairly high requirement for political loyalty.[4] Nevertheless, Armenia guaranteed certain rights to its citizens even residing outside Armenia, including the political right to vote from abroad.

An analysis of the citizenship policy of Armenia shows that it was during the Ter-Petrosyan administration that the principle of civic nationalism was strongest. Compared to future administrations, we can categorize it as “Armenia-centric”։ the emphasis was on prioritizing those who had tangible connections to Republic of Armenia (past or current residency, knowledge of the Constitution, etc.) This approach had its critics, both in Armenia and especially among ethnic Armenians living outside Armenia.

During the Kocharyan administration, a number of important developments took place, including the return of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation to the political arena and its inclusion in the Government. The changes were meant to appease the affluent and organized circles of the diaspora, as diasporan involvement in the development of the country became more widespread during this period. It was presumed that diasporan resources could counterbalance and neutralize Azerbaijan’s increasing capabilities, which were largely conditioned by oil exports.

The first substantial change in the Law on Citizenship took place in the spring of 2001, when former Armenian SSR citizens of non-Armenian origin living abroad who did not have citizenship of another state were deprived of the opportunity to obtain Armenian citizenship. In the absence of statistical data on applications, it is difficult to estimate how significant this legislative change was for former USSR citizens of non-Armenian descent. However, this change signaled the direction of the policies of the following years: departure from an Armenia-centric approach towards a more Armenian-centric approach manifested in the abolishment of almost all significant conditions for providing citizenship to those who had Armenian origins.

The 2005 edition of the Constitution abolished the prohibition on multiple citizenships, as well as prohibited depriving a citizen of their Armenian citizenship.[5] The Law on Citizenship was changed accordingly in the spring of 2007 to implement and regulate the provisions of the constitutional amendments. Essentially, these were profound changes, according to which:

- the requirement of knowledge of Armenian was eliminated in a number of cases, including for those who were of Armenian descent,[6]

- upon acquiring or receiving citizenship of another state, there was an obligation to inform the Government of Armenia within a month, envisaging responsibility in cases of non-compliance,

- the right of citizens to participate in Armenian elections from abroad was abolished.

Parliamentary debates over the last provision were quite heated. The prospect of having a large number of dual citizens voting from abroad introduced the possibility that other states may exert influence over Armenia’s policy directions. This view was voiced primarily by the Republican Party of Armenia (RPA). On the other hand, the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF), who had considerable backing in diaspora circles that were expected to apply for citizenship, stressed the importance of the right to vote of all citizens, including those residing abroad. Regardless of the validity of the arguments and the political calculations for the parliamentary elections to be held months later, it should be noted that this regulation was a step back from the already-established practice, which had permitted tens of thousands of Armenian citizens to vote in national elections at embassies and consulates: a tangible factor manifesting membership to a political community. It should also be emphasized that the right of citizens to vote from abroad is not an obligation stipulated by any international document; it is the sovereign right of each state to determine its expediency.

From the viewpoint of restricting political rights, the 2015 constitutional amendments were also problematic in that they banned dual citizens from holding a number of key positions. Dual citizens were constitutionally deprived of the opportunity to become a Member of Parliament, Prime Minister, Cabinet Minister, regional governor, judge, Government Ombudsman, or a number of other commissions, including the Central Electoral Commission. This restriction is discriminatory in not guaranteeing equal rights for all citizens, and has been repeatedly criticized by international organizations. As a rule, states that accept dual citizenship should also recognize the right of dual citizens to hold political and state positions. Moreover, there are many examples when the problem is solved not by banning the nomination of dual citizens, but by demanding the renunciation of the citizenship of the other state before assuming a certain position. However, the 2015 Constitution included durational requirements, ex. being exclusively a citizen of Armenia for the previous four years to become an MP. In addition, the actual application of this prohibition is problematic. In the case of a number of officials, the fact that they were a citizen of another state was discovered only after the fact (ex. former Minister of Defense Mikael Harutyunyan) or has been the subject of difficult-to-prove allegations (ex. President Armen Sarkissian).[7]

The next amendments to the Law on Citizenship were aimed at further liberalizing the conditions for granting citizenship. The 2011 amendments abolished the last substantial requirement for those of Armenian descent applying for citizenship[8]—knowledge of the Armenian Constitution—reduced the deadlines for reviewing citizenship applications, and later allowed for Armenians to apply for and obtain citizenship without visiting Armenia, through embassies and consulates.

Even a cursory analysis of citizenship applications based on Armenian descent raises a number of issues. First, as was expected, the exaggerated prediction that hundreds of thousands, even millions, of applications for Armenian citizenship would flood in did not materialize. Problems also arise in the procedures meant to prove the legislated condition of being “Armenian by origin” or later “Armenian by nationality”. In practice, unless a country records ethnicity on official documents (ex. Lebanon) a document from the Armenian Apostolic Church has been required, though ethnic origin and religion are different from each other.[9] There are also cases when citizenship applications are rejected on arbitrary grounds, like the applicant’s surname not sounding Armenian enough.

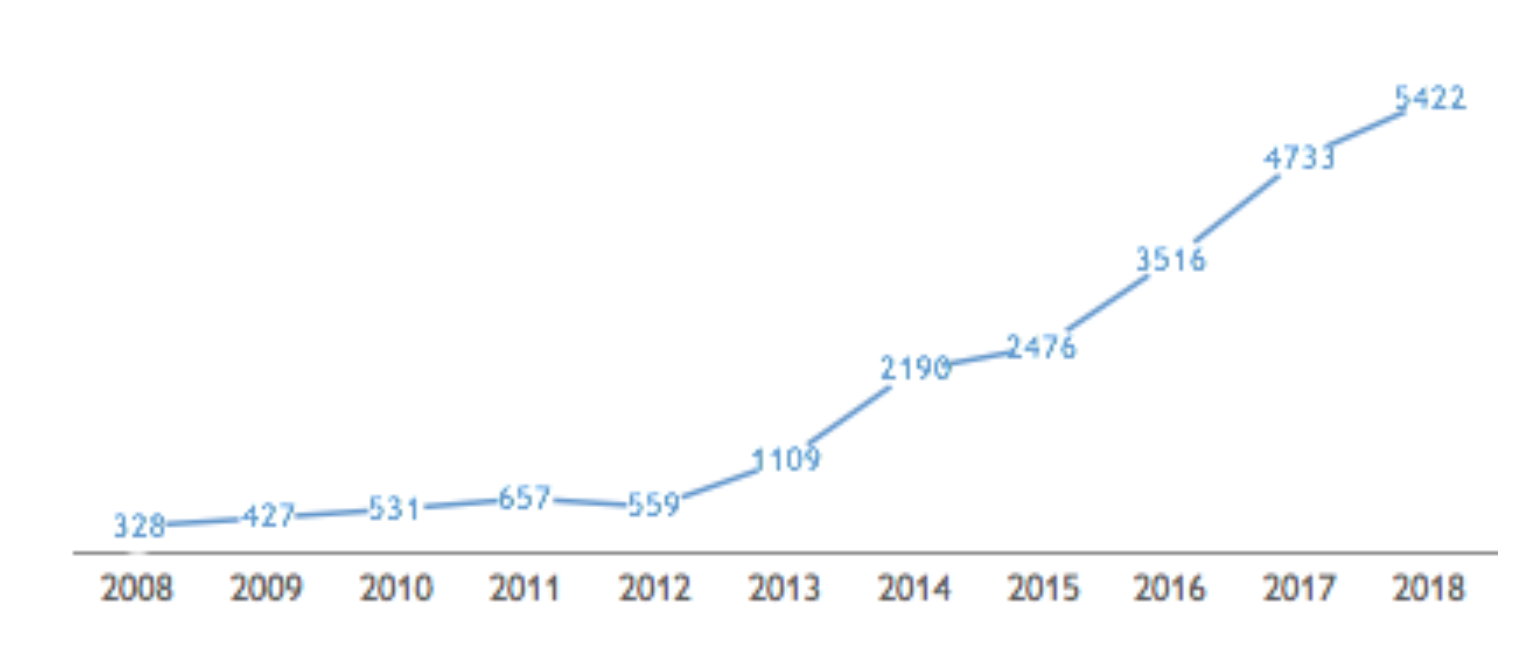

Furthermore, the lion’s share of applications by Armenians are associated with politically unstable situations in the applicant’s home country and acquiring Armenian citizenship would afford them certain opportunities. Once dual citizenship was fully legalized in 2007, the largest share of applications first came from Georgian-Armenians (especially from the Javakhk region), who were looking for a way to travel to Russia after the 2008 Russian-Georgian War. Armenian citizenship solved that issue but, at the time, given regulations in place in Georgia, Georgian-Armenians faced a number of issues, for many it even endangered their Georgian citizenship.

Parallel to the escalation of the civil war in Syria, the number of Syrian-Armenians applying for Armenian citizenship increased. According to some data, more than 90% of the approximately 30,000 Syrian-Armenians settled in Armenia during those years received Armenian citizenship. Armenian citizenship gave Syrian-Armenians the possibility to leave Syria safely, and a significant number of them settled in Armenia long term. However, it should be taken into account that receiving Armenian citizenship made them lose official refugee status, and thus making them and Armenia ineligible for international assistance programs when in fact Armenia had absorbed a significant number of refugees. In some cases, Syrian-Armenians who became citizens of Armenia used that status to travel to Western countries and later concealed that fact in order to obtain refugee status (essentially renouncing their citizenship). With deepening economic and political destabilization in Lebanon, a new wave of ethnic Armenians are immigrating to their homeland and applying for Armenian citizenship.

In conclusion, it is unequivocally positive that the Armenian state has been there for ethnic Armenians, especially in their most dire time of need, and welcomed them into the Armenian body politic with open access to citizenship. A gradual relaxation of restrictions on citizenship has widened the circle of those who are applying, including some whose previous ties to Armenia might not have been particularly strong. At the same time, however, the privileges of Armenian citizenship have been watered down for those who reside abroad and/or also hold other citizenships, by eliminating out-of-country voting and restricting them from certain constitutional positions. In effect, the evolving citizenship policy has normalized the possibility that an Armenian citizen may also tie their fate to association with a third country, reflecting the transnational nature of the global Armenian community.