Listen to the article.

That “the fact of genocide is as old as humanity,” does not prevent it from being a relatively young legal phenomenon. Moreover, it emerged from the ruins of post-WWII Europe as an innovative definition of an old yet non-prosecutable crime. It filled the gap of impunity left by the endorsement of the victorious allies of crimes against humanity, a legal concept drafted to prosecute Nazi war criminals and their collaborators.

The problem with the concept of crimes against humanity at the Nuremberg Trials was that the United States, the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union, and France intentionally confined it to acts committed in association with war. This was to prevent scrutiny of the numerous instances of mistreatment by the victorious nations of their own nationals before the war. The concept of genocide as an international crime eliminated that nexus with war. Subsequently, the “crime of crimes” can be committed both during armed conflicts and peacetime. The contemporary concept of crimes against humanity no longer requires any nexus with armed conflicts.

Genocide 2.0?

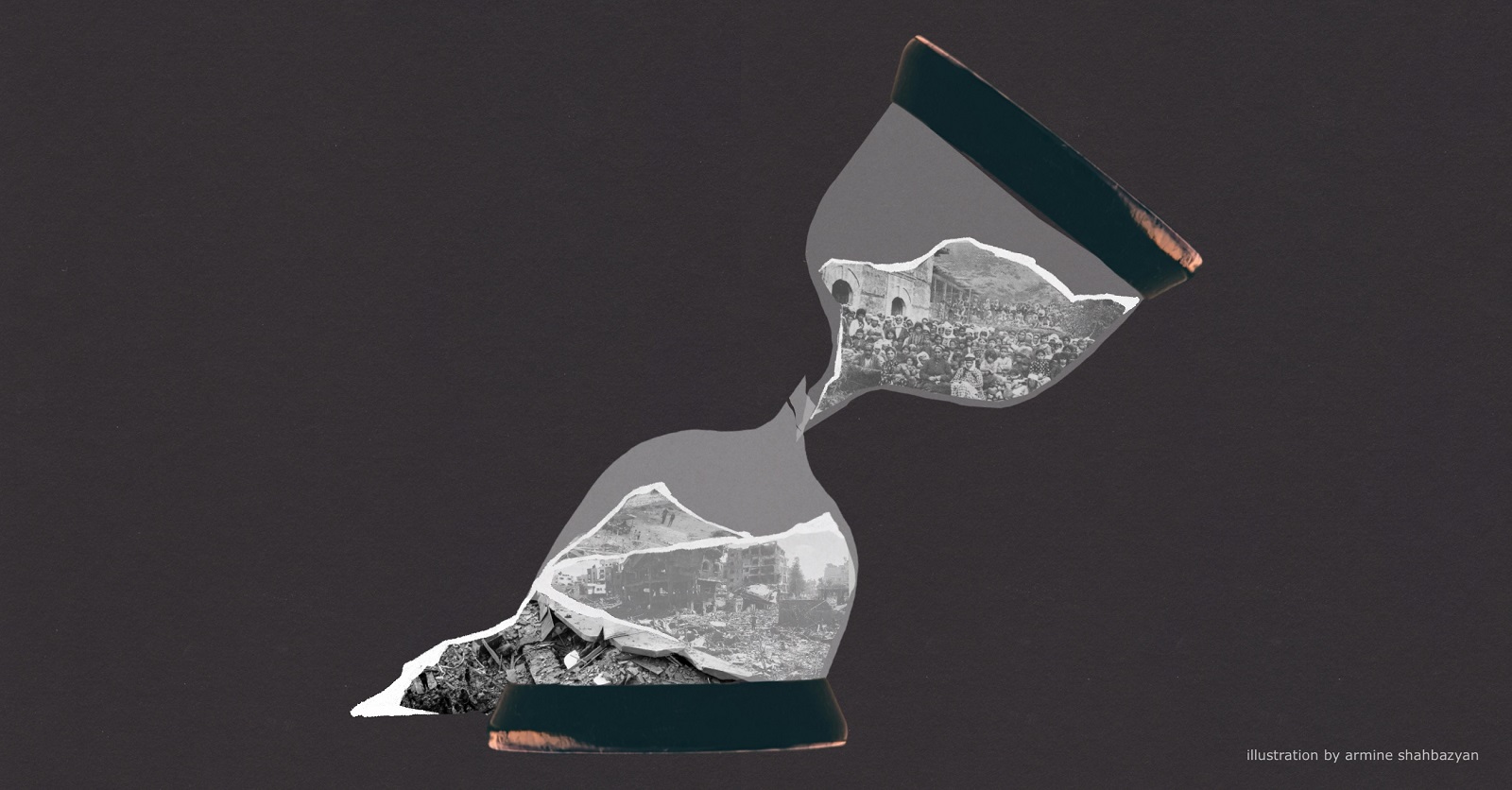

This article focuses on genocide from a slightly nuanced angle: throughout history, genocides have predominantly targeted populations under the effective control of their perpetrators—whether governments like the Nazi regime or the Ottoman Empire, or military leaders not necessarily acting on behalf of their states, as in the case of the Srebrenica genocide against the Bosnian Muslims.

And who could forget Rwanda? In just a hundred days, Rwandans turned against their own in a frenzy of violence that defies comprehension. But it does not stop there. From Pol Pot’s reign of terror in Cambodia to the bloodshed in Darfur, the story repeats itself. Although these last atrocities for various reasons do not entirely meet the definition of genocide under international law, these are not just isolated incidents—they too showcase the physical, spatial and temporal control over the victims.

However, there is a disturbing transformation underway. Genocidal acts appear to be adapting, occurring rapidly within military campaigns in both international and non-international armed conflicts. While it is crucial not to definitively label ongoing conflicts in Gaza or Ukraine as genocidal until the ICJ renders decisions in respective cases, they do raise reasonable concerns about the potential for such atrocities.

Dynamics in contemporary conflicts raise a poignant alarm about the all-encompassing impact of modern weaponry and military tactics, granting greater ease and speed to genocidal acts. On a global scale, it reiterates the urgent need for enhanced humanitarian protection of civilians during armed conflicts. The concept of genocide, originally intended to encompass atrocities during both peacetime and wartime, as recent history indicates, appears to be emerging primarily as a crime occurring amidst the chaos of war.

This shift is underscored by the resurgence of traditional inter-state armed conflicts, once thought consigned to history.

Control

The concept of control is a serious matter in law. Take, for instance, International Humanitarian Law (IHL), which aims to protect civilians amid the chaos of armed conflicts. Conditionally, IHL operates within two interconnected paradigms: Geneva Law and Hague Law.

Geneva Law prioritizes protecting those under a party’s control during armed conflicts. On the other hand, Hague Law governs the conduct of hostilities, aiming to shield individuals who are not yet under the control of any party but are targeted and affected by warfare. Moreover, the Hague Law sets forth limitations or outright prohibitions on specific weapons and tactics of warfare. Similarly, human rights law also hinges on effective control to determine its applicability. States are obligated to protect human rights wherever they exercise such control over people.

These legal details per se do not affect the crime of genocide. Genocide remains genocide regardless of whether it occurs during wartime or peacetime, under control or without it. However, these distinctions matter because genocide has traditionally been committed against populations under the perpetrator’s control. Whether it was the upheaval of two World Wars, international and non-international armed conflicts, or civil wars. The perpetrators of major atrocities typically held sway over their territory or occupied lands, exploiting the fog of war for their ends. Now modern weaponry and tactics enable what was once hardly conceivable—planning and executing genocidal acts from a distance, as a part of an overall offensive.

This shift does not necessarily mean we need to completely rethink how we understand genocide. Instead, it demands an unprecedented level of awareness and readiness from the international community to tackle major atrocities that shock the conscience of humanity. But for nations like Armenia, it is more than just an alert—it is about reshaping their security policies to face new threats. Or rather old ones delivered in new ways. The precarious security situation the nation currently faces highlights the potential for security threats to escalate into mass atrocities, possibly even genocide.

The situations in Gaza and Ukraine, though involving Israeli and Russian occupation respectively, differ significantly in their specific circumstances, which shape the nature of the atrocities committed in each conflict. As Professor Hersh Lauterpacht noted, IHL often operates in the margins of international legal frameworks, where even slight differences hold significant weight. Neither Israel nor Russia wields full, uncontested, and stable control over the populations they are accused of targeting for genocidal acts. What is critical to grasp here is the military context in which these alleged atrocities unfold. Israel’s military operations have caused enough concern that South Africa implicates Israel in committing genocide. Ukraine has also taken legal action against Russia for genocide before the International Court of Justice (ICJ).

Now, the rules governing the conduct of hostilities, Hague Law, add another layer to the discussion. This brings us back to the central premise of this article: the evolving nature of genocide in terms of its destructive power, methods of execution, speed and ferocity. Modern technologies and warfare tactics may lower the barriers to committing such acts. These advancements enable perpetrators to inflict harm without the need for complete control over the population, potentially accelerating the pace and scale of genocidal acts.

Furthermore, the framework of offensive operations minimizes potential accountability and liability for perpetrators, whether they are masterminds or executors of the crime. Establishing violations of Geneva Law, for instance, such as torture or killing of civilians in the power of the party, is comparatively easier than determining violations of Hague Law. Hague Law focuses on what and who was targeted rather than who was killed or what was destroyed. Whether an attack is lawful under Hague Law is determined by an ex ante evaluation by the attacking party, rather than by the outcomes of the attack. This necessitates extensive legal and evidential analysis. However, states naturally keep their military plans confidential, making it challenging for criminal courts and tribunals to determine the legality of a given attack. Consequently, potential perpetrators may perceive incentives of impunity in planning and executing genocide or other major atrocities under the offensive paradigm of Hague Law.

If Israel and Russia were to unleash intensive shelling, bombardment, and precision strikes from advanced aviation, alongside targeted attacks using drones and loitering munitions, they could decimate civilians and infrastructure in mere days, if not quicker. In cases where these attacks are carried out with the requisite intention, such actions could easily constitute one or several major atrocities. Large-scale indiscriminate attacks against civilians or deliberate targeting of civilian objects can lead to grave atrocities that surpass traditional war crimes.

Nations with more limited military capabilities can also adopt and adapt such tactics. Take Azerbaijan, for instance, which has shown its ability to learn tactics from various actors, particularly from Turkey and Israel. Given the opportunity, Azerbaijan could attempt to implement similar strategies with the resources at its disposal. Armenia must remain cognizant of this trend. Security calculations, including rearmament and military buildup, should account for the potential for genocidal acts within the context of armed conflict.

Whose Concern is Genocide?

If genocide shocks the conscience of humanity, and it certainly does, what should a conscious human being expect when confronted with such unspeakable horror?

In moments of unimaginable darkness, an individual may feel powerless, with little room to maneuver. Yet, this is precisely why societies and communities exist—to provide solace and strength when hell breaks loose. As Søren Kierkegaard once reflected, what happens to the bird does not concern it. According to the great Danish theologist and philosopher, our burdens are surrendered to a higher power. But humanity, in its resilience and resourcefulness (and hopefully not in its naiveness), has entrusted its collective security to other entities—primarily, the state. On a grander scale, we have delegated even greater expectations to the international community.

So, let us briefly look into what the international community, or any of its members, can do when confronted with an ongoing genocide on another state’s soil. Is military intervention feasible at all? And on a more practical note, how must a state act to safeguard its own people from such atrocities?

R2P and Humanitarian Intervention

Traditionally, states have been hesitant to intervene in each other’s internal affairs, and it is no surprise, given that the prohibition is enshrined in the UN Charter. However, the concept of the “Responsibility to Protect” (R2P) imposes positive obligations on states to safeguard their populations from genocide and other grave atrocities, such as crimes against humanity and war crimes. If a state blatantly fails to protect its population, the international community retains the option of military intervention under the UN Charter, provided the Security Council authorizes such action.

But what if it is not about R2P but an aggressive counterpart committing such grave atrocities in a state that is willing to protect its population but is overwhelmed? The doctrine of “Humanitarian intervention” suggests that in dire circumstances, other states could put boots on the ground to halt genocides, crimes against humanity, or war crimes. This is not yet the law; in principle, such intervention remains prohibited under Article 2(4) of the UN Charter—jus contra bellum, or the law prohibiting the use of force. Nonetheless, states sometimes sidestep the constraints of legal frameworks.

This is all the more vital given the UN Security Council’s pathological inability to overcome political rivalries and deliver what it must—sanctioning the use of force when it is critically necessary. One thing is abundantly clear: the drafters of the UN Charter, shocked by the unfathomable horrors of two World Wars, would never envision an international order that would turn a blind eye to major atrocities simply because the Security Council is bogged down in political bickering. Lessons like that could not have been unlearned so soon. Therefore, in certain cases, humanitarian intervention, while not formally legal, can be quite justifiable.

A prime example of humanitarian intervention took place during the brutal civil war in Liberia in 1990, which claimed thousands of civilian lives. In August 1990, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) established a joint military intervention force, the Economic Community Monitoring Group (ECOMOG). Acting unilaterally, without prior authorization from the Security Council, ECOMOG intervened in the conflict.

While ECOMOG’s success in enforcing a resolution to the conflict was limited, its intervention did help mitigate atrocities against civilians. In 1992, ECOWAS turned to the UN for support. Subsequently, Security Council Resolution 788 in 1992 not only commended but in fact ratified the intervention retroactively.

The bottom line is that intervention in the face of major atrocities cannot be dismissed outright. Yet, the fact that no state is intervening in Gaza militarily, despite abundant evidence of war crimes and crimes against humanity, raises troubling questions. Indeed, traces of major atrocities abound in Gaza. Israel’s military operations in Rafah, the last refuge in Gaza for 1.5 million Palestinians, will inevitably exacerbate the already staggering toll of nearly 35,000 lost civilian lives and devastating destruction of infrastructure. The prospect of even greater tragedy looms ominously.

On May 10, amid Israel’s operations in Rafah, South Africa for the third time asked the ICJ to indicate provisional measures against Israel. South Africa argues that Israel’s military assault on Rafah threatens the survival of Palestinians in Gaza as a group. Rafah stands as the last remaining area of the Strip largely untouched by Israel’s destruction. According to South Africa, “With Rafah’s destruction, the destruction of Gaza itself will be complete.”

So, why isn’t anyone putting boots on the ground? The primary candidates for intervention in Gaza—the U.S., France, the UK, and other major players in the EU and NATO—are either friends with Israel or friends of a friend. Traditionally hawkish regional states, on the other hand, either lack the capability or are wary of potential consequences from Israel and its allies, or both.

Secure Allies, Defense Foremost

No matter what, Armenia must fortify its security policies and military capabilities. While pursuing peace can be commendable, stable peace requires more than just diplomacy—it demands a clear, relentless, and non-negotiable commitment to self-defense. Even if humanitarian intervention is possible, strong armed forces are what will ultimately at least preserve what humanitarian intervention is coming to save.

Even if allies were to intervene with military force, Armenia must demonstrate its readiness and ability to protect its people in the meantime. The Ukrainian example speaks volumes: you must be able to punch back until aid in arms, technology, and finance arrives. Moreover, that aid would not have come without the initial grand pushback on the Ukrainian plains.

The advent of modern high-precision weaponry and large-scale, rapid military tactics has transformed the landscape of major atrocities, such as genocide. Russian strikes in Ukraine and Israel’s operations in Gaza serve as stark demonstrations of this potential. Modern military capabilities now erode the moral agency and enable the commission of genocide from a distance. Such crimes have become not only more feasible but also can als be carried out swiftly. So, is Armenia factoring major shifts like this into its security considerations? Is it prepared and willing to take up its R2P? Well, it must be, without question.

Also see

Can the International Community Reverse the Ethnic Cleansing of Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh? Part 1

The collapse of Artsakh is the failure of preventive diplomacy, the end of the human-rights-based liberal world governance system and can embolden other autocratic states to use force against small entities claiming self-determination to subjugate or eliminate them in other parts of the world.

Read moreCan the International Community Reverse the Ethnic Cleansing of Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh? Part 2

In the absence of political will to exert pressure on Baku to accept necessary preconditions for the security and fundamental rights of Nagorno-Karabakh Armenians, any calls for their return will only serve to legitimize and whitewash the ethnic cleansing that Azerbaijan carried out.

Read moreRecently Published

Hungary: Baku’s Friend in Brussels

Hungary recently blocked EU assistance to Armenia through the European Peace Facility, yet another move highlighting its strategic alignment with Azerbaijan, from supporting Baku's actions in Nagorno-Karabakh to blocking EU statements condemning them to extraditing a convicted murderer more than a decade earlier.

Read moreUnveiling the Challenges of Legal Education in Armenia

This article focuses on several significant challenges encountered by Armenian university students studying law, examining both the overarching concerns regarding the delivery of legal education and specific deficiencies within the system.

Read moreAzerbaijan-Israel Relations: Implications for Armenia

The deepening alliance between Azerbaijan and Israel carries significant implications for Armenia, notably Azerbaijan's considerable acquisition of advanced Israeli weaponry which it has extensively employed against Armenian forces in the past decade.

Read moreEthnic Cleansing, Genocide or Displacement?

This article explores the most accurate term to describe the de-Armenization of Nagorno-Karabakh by comparing various perspectives and examining the legal and political applicability of these terms.

Read moreEVN Report

Media Festival

Many vital topics, from obstetric violence to premature births, palliative care to menopause are often left out of the public discourse in Armenia. The importance of having honest conversations aimed at promoting understanding and awareness about these issues cannot be overstated. Featuring stories that challenge taboos surrounding these subjects is at the heart of journalism. Come and listen to the writers tackling these stories at the EVN Report Media Festival!