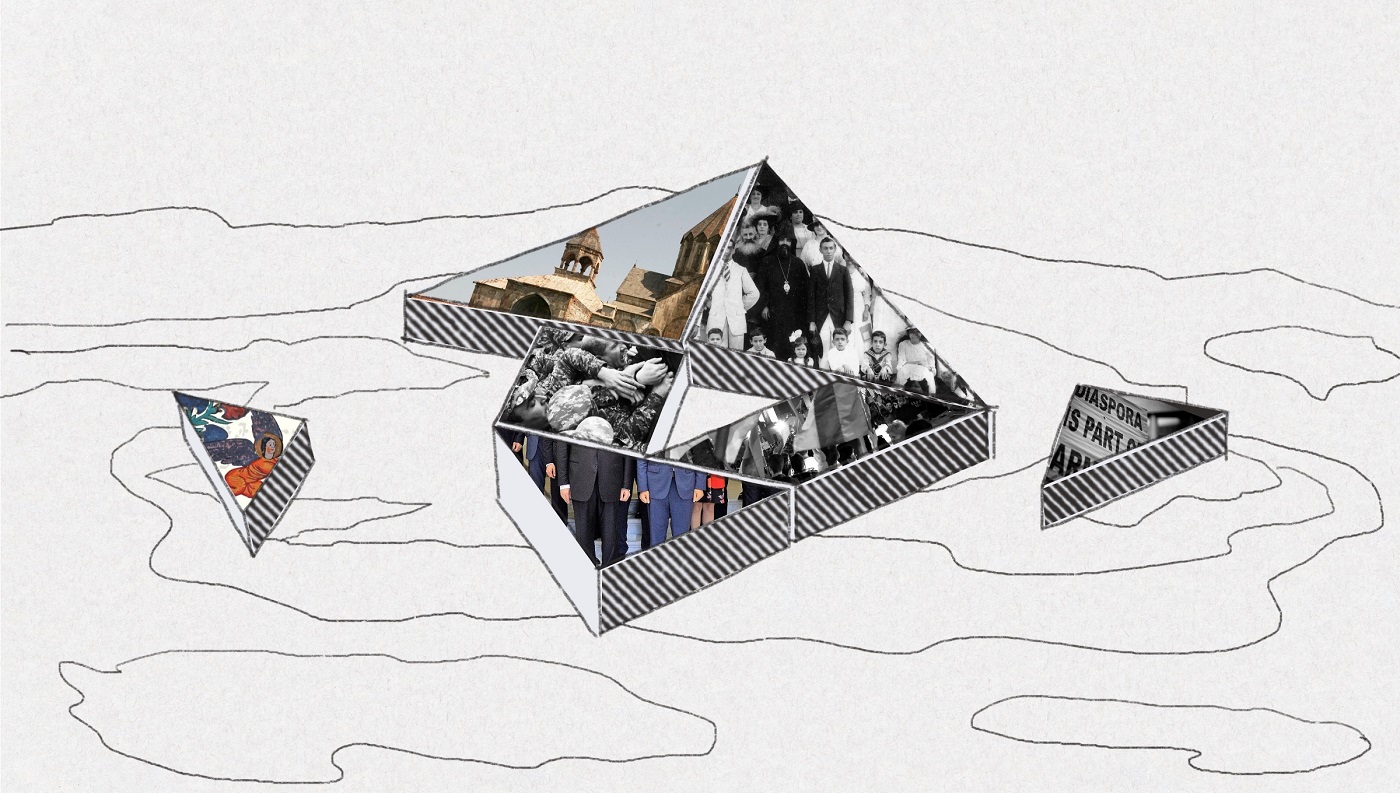

The recent upheavals and tragedies that have shaken the Armenian nation are forcing us to reassess the foundations of the Armenian cause, and the need to formulate an agenda with a strategic vision that includes new forms of political, intellectual and spiritual activism. This article explores different aspects of the Armenian cause from a diasporic perspective and attempts to generate ideas for continuing the debate on novel and meaningful foundations.

Since November 2020, the Armenian world has entered a phase of decline and loss of cardinal reference points. The syndrome of defeat, along with its territorial, material and psychological consequences, has had a lasting impact on our ability to perceive reality and act effectively.

Every morning, activists for the Armenian cause wake up with a sense of dread, fearing news of yet another devastating war with immeasurable consequences. Over the past three years, Armenia has been steadily diminishing. We are witnessing an unprecedented contraction of our civilizational space, without having considered the possibility of the worst-case scenario. History seems to be repeating itself, echoing the catastrophic war of 1920 when the Armenian provinces of Kars and Ardahan were handed over to the Turks, and then Shushi a century later. The Kars and Moscow treaties of 1920 have been mirrored by the tripartite agreement of 2020.

Abandoned by the government, the families of the missing and hostages are left without answers to their questions and endure unbearable suffering. The families of the young people killed are struggling to rebuild their lives in a country that is experiencing a moral collapse, as it neglects to address the structural flaws of its successive elites.

Political Irresponsibility

Reactions to defeat can manifest in various ways. Some individuals experience pure despondency, anger, or despair, and may even harbor self-hatred. There is often a sense of fatalism and denial of the right to life, often accompanied by guilt for surviving when so many young lives were cut short. Many believe that this ancient people is inexorably destined for extinction, similar to previous civilizations that vanished due to invasions and decay of the elite. In our case, it’s anger, particularly towards the successive rulers who have governed since independence. The tragedy of October 27, 1999, when the entire Armenian elite was decimated in parliament, holds great significance. This event overshadowed the formal declaration of independence on September 21, 1991, and shattered the dream of Armenian political sovereignty. It was symbolized by parliamentary president Karen Demirdjian representing the “glorious” past, and prime minister and architect of the national army Vazgen Sargsyan representing the future. On that same day, a new catholicos was elected under murky circumstances that remain unresolved to this day. Since then, Armenia has been on a slow descent into turmoil, politically fractured and spiritually tainted by the corruption of men and their egos.

No one in the diaspora fully grasped the gravity of this structural crisis. Over time, the Armenian cause’s agenda lost its substance. The call for recognition of the 1915 genocide no longer carried the same protest value. With the exception of a brief interlude in 2015, there is a reluctance to speak of moral, material, or territorial reparations with the Turkish state. The demand for respect for memory outweighs the rest. The lack of coordination between the key organizations dedicated to this cause (such as the Catholicosate of Cilicia, ARF-Dashnaktsutyun on a transnational level, Land and Culture, and private initiatives by lawyers in Armenia and the diaspora), has not yielded tangible results.

No wonder, then, that the diaspora and its political forces feel helpless in the face of looming dangers. The work of anticipation and prevention was not done beforehand. The issue of Artsakh has rarely been a priority for leaders comfortable with the illusion of an untenable status quo, except during crises as in 2016 and since autumn 2020. This raises the question of accountability. Are these leaders accountable? And if they are not democratically elected, how can they be held accountable? The idea of a democratic diaspora is purely imaginary, as there are no elections in any community that can designate representatives empowered to speak on behalf of the entire community.

Just as Armenia was weakened by the semi-authoritarian hybrid regimes of Robert Kocharyan and Serzh Sargsyan, the concept of political and popular sovereignty has not materialized. Armenian political thought still needs to differentiate between politics as tactics from politics as a responsibility, and as inclusive citizenship. This persistent misunderstanding can be traced back to the history of a stateless nation, when the Kingdom of Armenia in Cilicia (which was already a form of diasporic state) ceased to exist in 1375.

It is evident that the Armenian nation is struggling to see itself as a nation-state. The concept of the nation-state, with the state at its core, has never been firmly established in Armenian political thought. Even today, the discourse in the transnational Armenian public sphere often refers to the Armenian government as a “regime”, questioning its democratic legitimacy due to its perceived neglect of the Armenian cause (Hay Tad). Armenian political thought has struggled to define the boundaries of an Armenian nation-state with clearly defined borders. The manifestos of the revolutionary parties in the late 19th century rarely mention such borders. Armenians experienced political modernity too late.

Today, many Armenians criticize the revision of their national narrative, the exclusion of historical figures from school textbooks, the abandonment of the fight for a free Artsakh, and the renunciation of any claims on Turkey. This phenomenon contributes to a growing mistrust towards the diaspora, while also highlighting the irresponsible behavior of the diaspora, which is struggling to adapt. It is evident that successive leaders of both Armenia and Artsakh bear a significant responsibility for the current disaster. But the leaders of the diaspora should not evade their own responsibilities.

In the diaspora, there is no questioning, nor room for discussion about the mistakes and structures that led Armenian leaders to their downfall. The number of applications for Armenian citizenship in the diaspora remains relatively modest. The number of diaspora volunteers willing to join the Armenian army and participate in the defense of the national territory can be counted on one hand.

Absence of a Nation-state

Armenians have managed to survive for centuries due to the absence of a centralized state. With only a few exceptions, there has never been a concentration of sovereignty under one strong power. The Armenian Apostolic Church has served as the guardian of faith and, above all, of the continuity of national identity and its transmission. This is why the term “Church Nation” was proposed by French historian Jean Pierre Mahé.

Armenians have always been more confortable within multi-ethnic empires rather than nation-states. They excelled at building empires, but not nation-states, and constructing cities like Baku and Tbilisi. The 1918 independence came as a surprise but the Armenian Russophile military elite didn’t really believe in the possibility of building a fully independent Armenian nation-state. The political elites encountered major challenges in promoting a nation-state and uniting the Armenian nation around the so-called “Araradian” Republic of Armenia, as articulated by Boghos Nubar Pasha, president of the Armenian National Delegation. It was not until May 28, 1918, that Yerevan declared a free and unified Armenia, aiming to reconcile the two parts of the Armenian world – Eastern and Western. The notion that Eastern Armenia needed to persist in order to maintain the nation’s right to reclaim Ottoman Armenia did not gain support. In 1991, only a few deputies to the Supreme Soviet objected to the new independent state being named the Republic of Armenia in remembrance of Western Armenia, thus they suggested renaming it “Eastern Armenia”.

During the term of office of Levon Ter-Petrosyan (1991-1998I), only a few ministers and deputy ministers participated in the construction of the Armenian state. The diaspora was largely excluded from this process. The issue of dual citizenship posed a major obstacle until the 2005 constitutional reform. In the minds of Armenia’s leaders, it was deemed undesirable for diaspora nationals of foreign countries to become full citizens of the Republic of Armenia without first completing their military service in Armenia.

To build a strong nation-state after a defeat, Armenia must develop key sources of power related to defense and diplomacy. In both areas, the diaspora is not actively involved. The recent passing of Christian der Stepanian, a Franco-Armenian diplomat who dedicated himself to serving Armenia by working in the diplomatic service of the young state at the International Organization of the Francophonie and UNESCO, serves as a remarkable example of the positive collaboration between the Armenian diaspora and the nation. Unfortunately, his experience and career have not been replicated by others in the diaspora. Today, there are 4,200 individuals with French-Israeli citizenship serving in the Israeli army. How many diasporans have opted to enlist in the Armenian army to serve in a country where they neither reside nor have any family? Since 2020, there are significant reasons to believe that a new generation will grow up with a sense of defeat, resignation, and polarization.

The question of regulating the relationship between the Armenian state and the main diaspora organizations needs to be updated and critically examined. This is important to avoid confusion between lobbying and diplomacy in the future. Above all, the Armenian state should be able to support the development of the agenda and vision of the most strategic diaspora communities.

From this perspective, the diaspora’s only possible and desirable outcome is to demonstrate professionalism. This entails mobilizing material and symbolic resources to adequately compensate individuals who dedicate a significant amount of time to working on concrete projects. But for professionalization to occur, the structures must be strong, modern and attractive enough for young talent to find fulfillment. Another essential point is accountability: for professionalization to take hold, employees must be answerable to their employers.

However, the question of democratic debate within diaspora structures has not been thoroughly discussed. Even in France, where the Armenian community has managed to establish a supra-community body to advocate for Armenians to the French public authorities, there is no genuine democratic practices or objective representation of the Armenian community.

One way to approach this is by examining past examples that have been successful. The “Armenian National Constitution” of 1863 is a case in point. It governed the Armenian Millet of the Ottoman Empire and had the advantage of establishing various representative and diversifying bodies. These included a national assembly composed of lay and religious people, an executive office in charge of political affairs, an office for educational and school affairs, an office for religious affairs, and an office in charge of managing the community’s property.

In the highly fragmented context of the diaspora, establishing an Armenian parliament in exile may not be very realistic. However, the idea of more flexible transnational structures, with a mandate and legitimacy based on the electronic vote of supporters of a given project, does seem to offer a glimpse into the future. Similarly, there is an urgent need to focus on higher education by creating an online university that offers relevant subjects. These could include the history of Armenia and the Armenian people, strategic thinking, Armenian and foreign languages (English, Mandarin, Russian, Turkish, Arabic, Azerbaijani, French, Spanish, etc.), geography of the Caucasus region and the Middle East, international relations, political science, art history, and theology. Such an initiative would help equip younger generations for the challenges of today and tomorrow.

The Armenian diaspora is in urgent need of reinventing itself and embracing politics as a collective project rather than an individual pursuit focused on personal achievements or the duty of remembrance.

To foster this transnational political awareness and cultivate it in people’s minds, the role of the media is crucial. New digital media, analysis and information must support the transition from a diasporic mindset to a more professional form of transnationalism, based on existing and future networks for young professionals and students. This requires a new narrative that mobilizes and promotes a positive representation of Armenian identity. It is essential to contemplate the Armenian world of tomorrow and address the pressing question of what we can contribute to the global community to exist collectively in an increasingly threatening environment.

Also see

Diaspora Models, Part 7: Is There an Italian Diaspora Model?

An old nation but a young state, Italy shares many similarities with Armenia. In this next installment of a series on diaspora models, Tigran Yegavian writes that Italy must reform its nationality and emigration policies if it is to optimize its relationship with its diaspora.

Read moreDiaspora Models, Part 6: India

Despite being the second most populous country in the world, India has a relatively small diaspora. Still, they number nearly 25 million Indians in the world and are a major asset for the Indian economy.

Read moreDiaspora Models, Part 5: Ireland

In this series of articles, French-Armenian journalist Tigran Yegavian explores the complexity of relations between the Republic of Ireland and its diaspora.

Read moreDiaspora Models, Part 4: Greece

There are several million Greeks living in North America, Western Europe, Oceania and Africa. What are the specificities of the Greek diaspora model? This is part four of a series of studies on State-Diaspora relations.

Read moreDiaspora Models, Part 3: Israel

What are the tools available to Israel that strengthen the synergies between Tel Aviv and Diasporan Jews? This is part three of a series of studies on State–Diaspora relations.

Read moreDiaspora Models, Part 2: Portugal

In this article, journalist Tigran Yegavian looks at how Portugal has developed effective tools to strengthen its relationship with its diaspora and assert its international presence.

Read moreDiaspora Models, Part 1: Switzerland

As prosperous as Switzerland is, it has long been and remains a country of emigration, however, there are a number of structures available to Swiss communities abroad to ensure an optimal relationship with the country of origin.

Read more