Anyone who has ever lived in or has roots in a crisis-ridden place outside the West or on its fringes knows the feeling. Your homeland may be going through an existential crisis that means very little on a global scale, even as a small, miscalculated move may spell disaster in your corner of the world. That world being what it is—still very much dominated by a disproportionately powerful West—every report, every comment, every analysis coming out of Washington DC or Brussels, or Paris, or London, is weighed with much trepidation. The opinion—informed or not—of Western talking heads becomes the lodestar of objective reality, of what “the civilized world” thinks of what is going on in your neighborhood.

We now formally live in a post-colonial era. Yet, the frustration that accompanies the circumstances outlined above emerges from a feeling of powerlessness based precisely on an echo of a more openly unequal epoch. The West invented modernity; it exported it to—or, rather, imposed it on—the rest of the world. And while it may have, strictly speaking, retreated to its pre-colonial boundaries, it still shapes today’s world simply because it created it, and its fundamental rules: how people(s) are governed “correctly”, how economies are “properly” run, how to engage in “objective” science and scholarship, what styles of art are valued, and so forth.

The West remains powerful, not just because of the way it can directly shape various fields of human activity—political, economic, cultural—but also because at least some of its power comes from Westernness itself. That “Westernness” is a source of what the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu calls “symbolic capital”, a power that emerges from an external attribute which imbues the bearer with additional authority: think of the heroism associated with a military medal, or the assumed knowledge that comes with a diploma. The military hero or graduate gains that extra bit of power based on the credibility and status these symbolic markers provide, regardless of whether they possess the qualities denoted by a medal or diploma. They might, in fact, be cowards and ignoramuses; with a paid-for medal pinned to their chest, or a purchased diploma displayed in their office – one will never know.

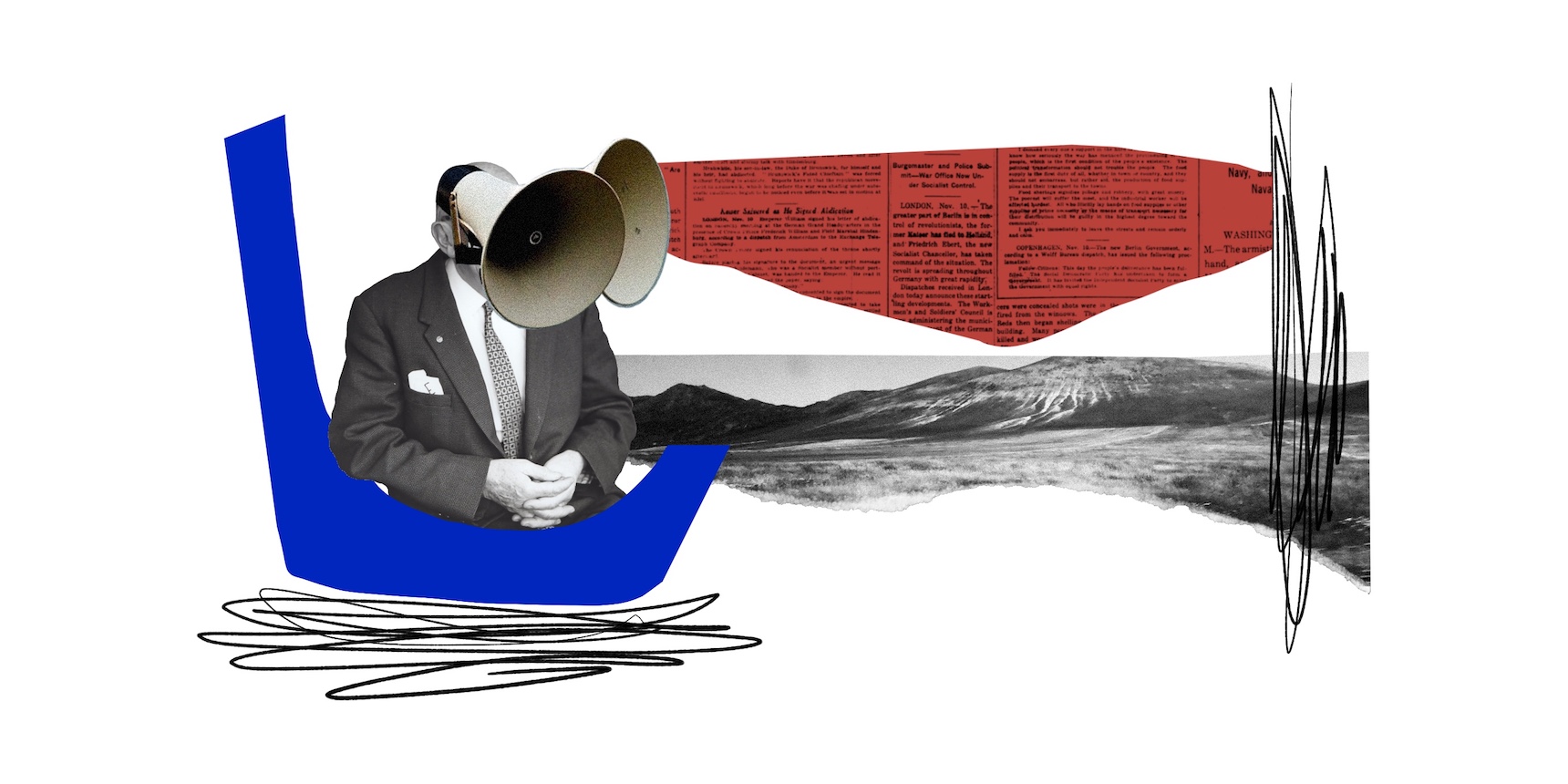

Similarly, being a “Westerner” imbues you with a kind of power that non-Westerners don’t have; in a world fundamentally shaped by the West, the very status of “being Western” comes with the assumption of superior power, wealth, knowledge, style others do not automatically possess. Individuals associated with Western universities, mass media, corporations, and governments are simply seen as more credible because of those associations in themselves, whether or not they are indeed more politically well-connected, rich, or culturally savvy. It is an ingrained prejudice that hides what are, in fact, unequal power relations inherited from a world shaped by empire.

At this point, many of you will be wondering what, exactly, this has to do with the Caucasus, Armenia, and Artsakh, although some will also no doubt sense where this argument is headed. Not having the good fortune of having been born into “Westernness”, many Armenians—especially those from the Republic of Armenia—often find themselves in the situation described at the beginning of this piece: hanging on the lips of this or that Western scholar, analyst or journalist explaining the ins-and-outs of a conflict which, to them, is a far-away matter in which they have little direct stake.

One might think that this outsider status alone implies a guarantee of “objectivity”; but let’s get that misconception out of the way right now. The very same French sociologist mentioned above, Bourdieu, also rejected the idea that a single observer—scholar, analyst, journalist—could grasp objective reality as an absolute, like an astronomer observing the inanimate universe, or a physicist studying Newtonian physics. It is not so much that objective reality doesn’t exist, it definitely does; but when it comes to studying human interaction, the observer cannot deny or escape their position within that reality. However distant and aloof, in an interconnected world, every onlooker will perceive things based on their own unique, historically conditioned biases, often distorted by relations of power with their subjects of interest. The best one can do—again, according to the same Bourdieu—is to be maximally reflexive: that is, to be aware, to as great a degree as possible, of one’s own biases, of one’s own—often privileged—position within the social space one was observing.

Rather than idealizing the perspectives of observers’ looking in from the West as inherently “objective”, one would have to look at them as imperfect attempts to understand objective reality through the unique prism of Westernness – or through what scholarship refers to as the “Western gaze”. This “gaze” does not provide an untrammelled insight into objective reality; instead, in our still-unequal world, it is normalized, unthinkingly accepted, as “objective”. Its authority rests on a privilege founded on unequal power, rather than an all-encompassing “scientific”, “rational” grasp of reality. It is shaped by centuries of colonial rule over the rest of the world, and the in-built assumption that the West—often not accidentally referred to as the “International Community”—has a unique grasp on setting standards, drawing boundaries, adjudicating between right and wrong, determining the “correct” form of government, and so forth. It is usually the Westerner that studies and judges the non-West; it seldom works the other way round, and if it does, it is much less impactful, because ultimately, power still lies in the West.

This presents others on the lower rungs of this global hierarchy with a problem: firstly, even if Western scholars, journalists, analysts approach them in good faith, their decisions are of much greater consequence in view of their embeddedness in the global “core”. But whereas these distortions and biases may be morally acceptable when they are made in good faith—even if their proponents might want to consider a more reflexive attitude and be more conscious of their biases—that is no longer the case as one descends onto groups that do not act out of well-meant, if imperfect, interest. I will refer to them in descending moral order as useful idiots, Western supremacists, and, finally—as the lowest of the low—”white monkeys”. Let’s go through these categories one by one.

The good-faith observers at the top of this moral hierarchy report, analyse and theorize while fully acknowledging the complexity of the subject they are reporting, analyzing or theorizing. Their works are at least bona-fide attempts to tackle thorny issues in far-away places like the 1915 Genocide or the war in Artsakh “fairly”, in an honest search for truth. This does not mean that their approaches will be perfect. As implied above, many of them, especially those who fail in the difficult attempt to be reflexive about their own position of power, will at times end up reproducing the Western dispositions that are well-known to inhabitants of “the Rest’: the use of double standards, the drawing of lines on maps, the talking down to locals as “emotional” and “irrational”. All of this can be quite irritating, and at times enraging to those at the receiving end; but, ultimately, the good faith behind these aberrations keeps the door open to dialogue, and calls for greater reflexivity on their part.

Things go downhill and engagement becomes largely useless as we descend the moral pecking order and reach the realm of useful idiots: in the current context colloquially known as “tankies”—but also Western supremacists—some of whom are also referred to as “neocons”. These two categories have something in common: the assumption that the world is simple, and that it is, in essence, a morality play between good and evil, light and darkness, the West and the anti-West. The main difference between them lies in who exactly they identify as “good”, and as “evil”. Tankies will usually point fingers at the West as the world’s only and ultimate source of wickedness, whatever the circumstances, regardless of what the locals in any given situation want and in the process, end up supporting questionable regimes as long as they are perceived as anti-Western. Revolution in Armenia? It must be the CIA. Uprising in Hong Kong? Surely, it is the Hong-Kongers being manipulated by the National Democratic Institute. War in Ukraine? That’s all about “NATO imperialism” and nothing to do with the kleptocrats in the Kremlin.

Western supremacists, on the other hand, take it the other way around: to them, the West has an entitlement to rule and divide the world neatly into pro-Western and anti-Western countries, and essentially wish death and destruction to anyone on the wrong––“evil”—side. If tankies suffer from self-loathing, these supremacists display a distinct God complex, standing in judgement over whole states and nations as if geopolitics is a matter of black and white. Like their tankie counterparts, they also often come to support vile regimes—as long as they are, or present themselves as, pro-Western––Iran being the ultimate evil, and “anti-Iranian” and “pro-Western” Azerbaijan being “good”. Armenia’s alliance with Russia is simply an “evil” choice rather than the result of the complexities of history and geopolitics. As for states in the global South, in Africa or Asia, not following sanctions imposed on Moscow by the West? That must be because they are unduly corrupted by the “other side”, rather than out of a genuine concern for their specific national interests. You are either with us, or against us; and woe unto you if you find yourself on the wrong side of this equation.

In a more equal world, both these groups would be dismissed as the inconsequential, extremist cranks they should be seen as. The problem is, however, that they both have a certain disproportionate power by gist of their influence on Western narratives: consequently, their thoughts and deeds often matter more than those of even the most knowledgeable non-Westerners. Born out of ignorance or ideological zealotry, their words can infect public opinion, move policy, and hurt real people. By virtue of their dogmatic anti-Western stances, you’ll find tankies usually banished onto social media, where they can still wreak havoc by denying genocides, discrediting humanitarian organizations, ridiculing pro-democracy movements, and spreading conspiracy theories. Western supremacists, by contrast, are quite often also welcomed as “patriots” in quite a few places outside the cybersphere. In fact, you’ll regularly encounter them in the offices of right-wing think-tanks, where they churn out simplistic analyses, without so much as losing an ounce of credibility in the process. In that sense, they are the more damaging of the two, especially if you find yourself on the wrong side of their puerile worldview.

And so, we have reached the most pernicious element affecting information flows surrounding small non-Western states and nations, including Armenia, in the 21st century: the “white monkey”. The term refers to a phenomenon seen in East Asia, where White individuals gain employment by local businesses to, essentially, be seen at an event––a business meeting, or grand opening, and stand around, smile, and be pretty. The presence of a Westerner is seen to attribute more credibility and international prestige to their employers. In effect, these individuals are selling their “Westernness”, and the symbolic capital that comes with it, to the highest bidder. Just like the heroism that comes with a medal, or the assumed knowledge that comes with a diploma, the qualities associated with that “Westernness” are seen as rubbing off on those employing the “white monkey”.

As in the East Asian cases mentioned above, corrupt, often oil-rich dictators outside the West, including but not limited to the Aliyev regime, have learned to employ “white monkeys” to do their dirty work for them, because PR—the modern term for propaganda—is much more credible when delivered by someone with a culturally familiar name and “European” appearance. Outright lies can be gotten away with because of the toxic combination of excess symbolic capital, and the assumption that native voices furiously protesting those lies are, by definition, biased and subjective, and, therefore, not to be trusted.

Monetized or not, paid for by dictatorial regimes or not, the excess symbolic power that comes with “Westernness” explains how some authors and commentators on the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict can get away with the most outrageous gaslighting, at times engaging in outright racism. The Armenian diaspora is thus dismissed as an amorphous mass of extremists prone to terrorism. The nation’s political culture is reduced to one-dimensional platitudes about “ethno-nationalism” and Nazism. Atrocities are invented; ethnic cleansing minimized or excused. Dog-whistle allusions to the imaginary power of a worldwide Armenian conspiracy––the “Armenian lobby”–– are made. The tragedy of war is treated as a football match, one side openly cheered on as if it is all a game. Talking points directly taken from a dictatorial regime’s mendacious historic and contemporary narratives of erasure are mindlessly reproduced, over and over again. Demons on one side, angels on another, in article after article, screed after screed.

They needn’t worry. Even if many of the stereotypes and generalizations voiced above would be instantly recognizable as racist tripe if they were directed against, say, Jewish or Muslim diasporas or communities, excess symbolic capital combined with a general ignorance on the realities of the South Caucasus in the West ensures few consequences for those voicing them. In fact, many of these misstatements have been deemed publishable both on social and in traditional media in recent years and months; and there has so far been very little pushback against these discourses from people who should know better, but prefer to remain quiet in the face of bigotry and falsification.

In a region few know or care about, too many useful idiots, Western supremacists, and white monkeys have, too often, used their positions of power as an extremely effective protective shield. And this has brought a moral rot into the reporting on and the study of the South Caucasus, where more credible and balanced voices are increasingly shouted over. It is time to address this failure or see the information environment on this part of the world putrefy beyond repair.

Opinion

The Holy Alliance for Getting Out of a Quagmire

Armenia has been facing an impasse since the defeat in the 2020 Artsakh War. It is imperative that Armenians break with defeatism and desolation by putting differences aside and focusing on what is essential: national security.

Read moreSpotlight Karabakh

Where Is Yerevan as Armenian Villages Handed Over?

As the Armenian villages of Aghavno, Berdzor and Sus on the Lachin Corridor were handed over to Azerbaijan on August 25, questions remain about why Yerevan was seemingly excluded from that process.

Read moreLaw & Society

Declaring Income and Assets: Risks and Opportunities

Starting from 2024, the declaration of income and assets will become mandatory for all citizens of Armenia. Araks Mamulyan looks at the advantages and problems of the program.

Read moreEt Cetera

Kafka in Artsakh

Garegin Papoyan’s film “Bon Voyage” manages to recreate a Kafkaesque world in the form of the Stepanakert Airport, where people follow a seemingly unreasonable system, and continue to do their work with incredible persistence, without questioning its meaning.

Read moreMagazine Issue N21

Climate Change

How post-Soviet de-industrialization Became Armenia’s Opportunity for Renewable Energy

For Armenia, domestic energy production is not a mere vanity goal, but a national security priority. As a country devoid of any apparent fossil fuel deposits, energy security means renewable energy. Raffi Elliot explains.

Read moreEnvironmentalism in Armenia: Awareness, Education and Empowerment

As the world is experiencing the effects of climate change, the accumulation of waste, which contributes to greenhouse gas emissions, should not be left out of the conversation.

Read moreThe Impact of Global Warming in Armenia

Armenia is a country highly vulnerable to climate impacts. The most vulnerable sectors are agriculture, water resources, forestry, transport and energy infrastructure. Is Armenia’s government doing enough to mitigate the impact of climate change?

Read more

A very good piece, however, I would prefer names identified and examples given as well, otherwise it lacks some substance. Also, the ‘opposite side’ says the same about the Armenian version supporters. What to do about that? But thanks for addressing this issue again that we have been communicating about, on and off, since the ‘Hayastan’ group of Asbed, since 1994, when the www did not even exist yet, and only email was available.

Isn’t it the same for the recognition of the Armenian Genocide? 20-30 western countries have recognized it and there’s this tantrum that it is the objective truth. Anyone who doesn’t have a western education or similar opinion is dismissed. Reports (or Ottoman sources) that contradict are either dismissed, considered partial or forged (as if western sources are always impartial). Armenian Diaspora organizations have made use of the narrative hegemony of the west to pressure against Turkey since decades.

Absolutely incorrect use of the term hegemony. There are ample written sources in Arabic and in Farsi. Both Arabs and Persians have long noted the genocide and it is part of the historical record in writing and oral history.

There is no both-sides to this power dynamic you allege. Armenians were nearly wiped out. Everyone in the Middle East knows this. It is common knowledge, and the western avenue of recognition actually acted as blockades to reparative justice.