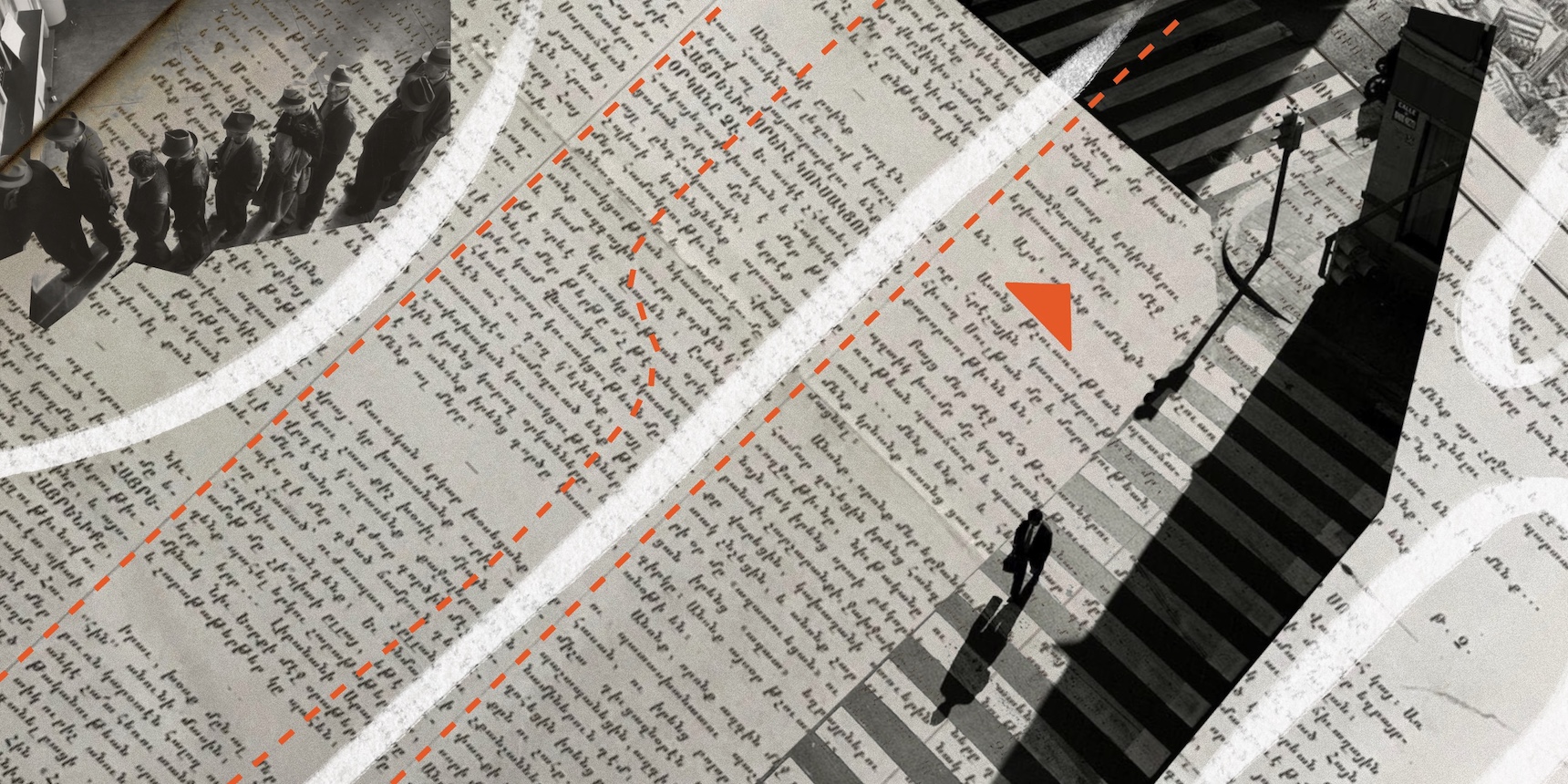

Armenians have a rich tradition of writing, fueled by their tumultuous history and early geographical dispersion. This has led to a strong appetite for text, particularly the press. As Karlen Mooradian notes, “Armenians have created perhaps more periodicals per capita in four quarters of the world than any other people.” For centuries, Armenian press titles have numbered in the thousands, forming a remarkable network extending from the Far East to South America and from Europe and the Near East to Africa and Oceania. On October 16, 1794, Father Harutyun Shmavonian printed the first monthly newspaper in Armenian history, Aztarar (Monitor), in Madras. As it was also the first newspaper of a Near Eastern people, Shmavonian is considered the father of Armenian and Near Eastern journalism.

Four Great Figures of Journalism

It would be impossible to list the names of the great figures of Armenian journalism who have left an indelible mark on our modern history. However, we must remember Krikor Ardzrouni (1845-1892), whose name remains associated with his newspaper, Mshak. This political and literary daily was established in Tiflis (now Tbilisi) and was a pioneer of political liberalism from 1872 to 1920. It advocated for a reunified Armenian state attached to Russia and emulated the Armenian revolutionaries of the Caucasus.

Azadamart of Constantinople was a major daily opinion outlet affiliated with the ARF-Dashnaktsutyun. It was founded in 1909 by writer and teacher Roupen Zartarian (1874-1915), who served as its editor. Zartarian was a fervent supporter of Ottoman liberalism.

Another forgotten figure of immense influence in Armenian journalism was Diran Kelekian (1862-1915), a professor at Istanbul University, and journalist and editor of two major Ottoman dailies –– Cihan and Sabah. A refugee in Cairo during the Hamidian persecutions, he worked there as editor-in-chief of the French-language daily Journal du Caire, while also working as a correspondent for the Daily Mail, the Daily Graphic, and the Associated Press. Kelekian authored a Franco-Turkish dictionary and even published a newspaper in Turkish using Armenian characters.

Shavarsh Misakian (1884-1957), a journalist and intellectual who survived the genocide, worked for many newspapers in Constantinople and eventually became a member of the editorial staff of Azatamart. In 1925, he founded the famous Haratch in Paris, which was the first and last Armenian daily newspaper in Europe, lasting until 2008. Haratch was a beacon of hope during difficult times, providing a platform for young intellectuals and writers from the diaspora. It raised awareness not only of the lost country, but also of the diaspora itself as a spiritual entity and community of readers, who were faithful subscribers scattered around the world. Haratch was the only foreign-language daily newspaper available in Paris, aside from the local edition of the New York Times.

A Precarious Situation

There are numerous newspapers of various periodicity that have housed Armenian thought. However, due to a lack of transmission, younger generations are largely unaware of their existence. In the diaspora, the press was a precious link that helped maintain the coherence of a deterritorialized Armenian society, alongside the Church and Armenian schools.

Armenia’s independence in 1991 brought about a new situation. The ARF-Dashnaktsutyun, which emerged from underground, founded the Yerkir newspaper, which now exists as a news site and a television channel. The Ramgavar party founded the daily, now weekly Azg, which remains one of the main platforms for Armenian opinion. It is one of the few media outlets that bridges Armenia and diaspora communities through a network of party supporters.

While these initiatives have made significant headway in reviving the Armenian media landscape, it is clear that the press and media in Armenia and the diaspora have not yet found a way to adapt to 21st century challenges. Despite a long tradition, the Armenian press struggles to adapt to the new information landscape.

One of the primary challenges faced by the Armenian media is the lack of formal journalism training programs in the diaspora. Currently, there are no Armenian journalism schools, and the few Armenian-speaking journalists in the diaspora are mainly from Lebanon and Syria. Although some work as journalists full-time, such as the editorial staff of Aztag, Ararad, and Zartonk in Beirut, or Marmara and Jamanak in Constantinople, they have generally received training in Armenian philology, where they are taught perfect Mesrobian Armenian, but rarely modern journalism skills.

I recall auditing a course at Haigazian University in Beirut, which was given by the former editor-in-chief of Zartonk, Baruyr Haghbchian. I also remember a workshop on the media, an initiative of France Armenie journalist Varoujan Mardikian for Armenian teenagers at Tebrotzsasser College in Paris. Additionally, I recall journalistic writing workshops organized by the editorial staff of Aztag in Beirut for young Lebanese Armenians. These commendable initiatives, however, cannot compensate for the lack of sustainable and professional institutions.

Journalistic training should aim to pass on technical knowledge, good writing skills, as well as the ability to distinguish opinion from analysis, and information from disinformation. It is necessary for journalists to produce radio and podcast shows, newspapers in paper and digital formats, but above all, it is necessary to have a readership. Unfortunately, dwindling numbers of Armenian-speakers in the diaspora has led community members to adapt and switch to bilingual articles or simply abandon Armenian.

In France, even with the high-quality monthly publications Nouvelles d’Armenie and France Armenie and bilingual weekly Nor Haratch, attracting and retaining readership is extremely difficult. Subscribers are solicited for annual renewals to sustain the publications. The shift to digital media and the use of new tools, such as filmed interviews on YouTube and podcasts, are unlikely to change this trend.

One thing is certain: there is currently no clear vision for the role of information content or the Armenian language as a means of transmitting culture and tradition.

The Press: A Victim of Armenian Society’s Polarization

Armenian media suffers from a lack of resources and a comprehensive vision for its role within the context of the diaspora and post-Soviet Armenian society. In the diaspora, community press survives on meager resources, as there is no state aid available. Partisan and community structures, advertisers, and subscribers play a more decisive role in its perseverance. As a result, there is no truly independent Armenian press in the diaspora, which is not unique in the global context.

Armenia has a high number of news sites relative to its readership, with some displaying good design elements and user friendly navigation. At the same time, the abundance of media outlets creates an illusion of pluralism that conflicts with the oligarchic reality, since many are owned by the same person. For instance, Mikayel Minasyan, the son-in-law of former President Serzh Sargsyan, owns several media outlets, including Tert.am, 168 Zham, and Panorama. Meanwhile, former President Robert Kocharyan also owns various media outlets, including Yerevan Time.

Another cleavage, this time geopolitical, exists between pro-Western media such as 1News.am, CivilNet, Azatutyun, and those who maintain a more pro-Russian stance like Tert.am and 168 Zham. It is the oligarchic domination of the mainstream information space that, during and after the Velvet Revolution, led Prime Minister Nikol Pashinian to favor direct communication with the public via social networks, such as Facebook, using and sometimes abusing it.

Invest in an Investigative Press

A major shortcoming of Armenian media is the absence of a professional investigative press in both Armenia and the diaspora. The Keghart outlet in Canada is a notable exception. This outlet has, among other things, published revelations around corruption in Jerusalem’s Armenian Patriarchate, which few media outlets have covered. In Armenia, Hetq, run by Edik Baghdasaryan, a prominent figure in contemporary Armenian journalism, is also a noteworthy exception. Baghdasaryan previously taught journalism at Yerevan State University.

Hetq, part of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and notable for its work on the Panama Papers, has recently reported on a number of cases of corruption involving high-level Armenian officials, including the recent below-market purchase of a Yerevan apartment by Defense Minister Suren Papikyan. Investigative journalism is a crucial tool for holding the powerful accountable for their actions.

Investigative reporting has taken on strategic importance in Armenia and Artsakh’s national security. Armenians lost the information war in 2020, unable to disseminate an effective narrative internationally to impact public opinion, unlike the Ukrainians. Additionally, the Artsakh Press agency rarely broadcasts images to the international community –– unacceptable in the current context of information warfare. Aside from important reporting from the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), very little has been done to investigate Azerbaijani corruption networks in Europe and around the world. Recent revelations about an Azerbaijani oppositionist persecuted by Baku in France could have elicited more international interest on this transnational repression, but no Armenian media has the resources to take up a serious investigation.

Advocacy for Armenian international broadcasting

Strategically, international media have abandoned short waves as they are too expensive and have shifted their focus to web-based platforms. Armenia’s Public Television and Public Radio have already begun producing and broadcasting programs for the Armenian diaspora. However, their traditional approach seems aimed at promoting patriotic feelings and emphasizes the originality of Armenian culture. While listeners nostalgic for the Soviet era may appreciate it, Armenian youth in the diaspora may not. The 2020 Artsakh War and its consequences have resulted in requests from a few hundred journalists of Armenian origin in France, North America, and Argentina to relay Armenia’s messages to their domestic audiences. In the past, the Armenian Ministry of the Diaspora held congresses of journalists from the diaspora, but these did not develop into anything impactful. At most, they managed to develop some synergies, such as the Armenian monthly Orer, published in Prague and managed by journalist Hakob Asatryan.

In the 30 years since gaining independence, very little has been done to ensure that Armenia, a country with a larger diaspora population than its own, and which is currently in a state of war, establishes an international TV channel capable of communicating its narrative and values. Meanwhile, the Aliyev regime has managed to gain favor with the BBC.

This would be a significant investment, but not an impossible one, given the available resources of the diaspora. Such an investment would serve the collective interest and would have the added benefit of attracting capital, human resources, skills, and people who may not be interested in the values of the slogan tebi yerkir, but who would be willing to come to Armenia to work in their field of expertise.

This satellite media should be broadcast in several languages, including Armenian in both its variants, as well as in English, Russian, French, and even Turkish, so that viewers from Western Armenia and the diaspora can tune in. It would serve as a bridge between Yerevan, Stepanakert, and the diaspora.

However, in order for this dream to become a reality, the first step is to establish an educational and training program for young diasporan Armenians in their respective countries, which includes a school of journalism. Armenian studies programs in the diaspora that offer continuing education should take into account that learning and teaching Western Armenian does not necessarily lead to a career as a teacher or linguist, as is the case at the National Institute for Oriental Languages and Civilizations (INALCO) in Paris.

Success depends both on willpower and on being part of a tradition –– a tradition begun by the Artsrunis, the Misakyans, the Kelekians, and the Zartarians. Their names, faces, and work are not meant to be merely portrayed in postage stamps or history textbooks.

Also see

Armenian Women’s Writing in the Ottoman Empire, Late 19th to Early 20th Centuries

“A male writer is free to be average, but never a female writer.” This is what 19th century writer Srbouhi Dussap told Zabel Yesayan when she announced she wanted to be a writer. Hasmik Khalapyan traces the extraordinary lives of Armenian women writers of the Ottoman Empire.

Read moreMagazine Issues

Books & Literature

Media

Recently published

Art as a Tool for Conflict Transformation and Healing War Trauma

Art can be an effective tool of conflict transformation impacting societal attitudes and perceptions by producing a cathartic effect on both artists and audiences, writes Anna Kamay.

Read moreEnvironment and Energy Through the Public’s Eye

Improvements in low-carbon technologies, driven in part by foreign energy policy, have created new opportunities for Armenia, a country without fossil fuel reserves, aligning environmental concerns and the pursuit of higher energy security more than ever before.

Read moreThe Mediterranean World and Armenia’s Relation to It

Being at the crossroads between East and West, Armenia has thrived only when these two forces were at an equilibrium and neither was strong enough to exert disproportionate influence on its domestic affairs. But what about its connection to Mediterranean civilizations?

Read moreUnregistered Employment, Lost Taxes, Compromised Rights

In the last three years, the number of reported cases of unregistered workers has increased in Armenia. Despite numerous legislative regulations and monitoring tools, unregistered employment remains a critical issue.

Read more