For more than a month Azerbaijan waged an undeclared war against the Republic of Artsakh and Armenia. Since the beginning of the hostilities, despite numerous calls for ceasefire and a return to peaceful negotiations, the international community by and large remained indifferent to what they consider a mere regional conflict. In fact, the war in Nagorno-Karabakh did not only upset the stability of the region, it also reflected the uncertain state of the world in general and stems from an issue that is perhaps more concerning than the war itself. One cannot help but notice the parallels between the geopolitical situation now and the one following the end of the First World War.

History has seen many empires or kingdoms that were at some point in time the hegemonic policing power in the world. Throughout the 19th century, the British Empire acted as the police state of Europe and the world at large. Burdened with an enormous debt following the aftermath of the First World War, the limits of Britain’s capabilities eventually became evident, leaving a power vacuum that had to be filled. A power shift in favor of the United States had already begun in the 1920s, but it was only after the Second World War that America established its long-standing global supremacy,[1] albeit in constant competition with the Soviet Union.

While the U.S. remains the foremost military power in the world, it is evident that today there are limits to its capabilities in the global arena. This could be because we are now living in a fractured, multipolar world that cannot be policed by a single state. On the other hand, since the Trump administration came to power four years ago, the U.S. has become more concerned with internal issues rather than external, international problems. While America is still reflecting on the presidential elections held earlier this month, there is doubt over who else can take this role upon itself. Europe has long been used to practicing mostly soft power. Its need to achieve consensus among more than 20 countries now more than ever confines it to words rather than action when it comes to reacting to global developments.

On the other hand, Russia is slowly trying to solve its problems with the European Union, most directly with Germany after the Navalny scandal and amidst delays in the construction of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline. A new series of sanctions against Russia might well be underway, and it is one of the reasons that makes Russia rather unable to let itself get embroiled in a new conflict. The other reason why Putin’s Russia remained rather cautious when a war was actively waged in its sphere of influence is that it has strong ties with both Armenia and Azerbaijan and cannot risk losing one by appeasing the other. The second biggest economy of the world, China, has weathered the storm of the pandemic better than the rest but still refuses to practice political influence in controversial matters, or maybe its time has not quite yet arrived.

All of these factors gave Turkey and its junior partner Azerbaijan a free hand to advance their strategic plans in their backyard. Since August, Turkey has been at odds with its supposed NATO ally Greece. After things came to a stalemate because of France intervening on behalf of Greece, it turned its attention eastwards; with the help of Azerbaijan, Turkey wants to extend its influence into the South Caucasus and Central Asia. As a result, the people of Artsakh and Armenia had to fight for their own existence against terrorists on Turkey‘s payroll and the war crimes of Aliyev’s regime. Moreover, there’s hardly any denying Erdogan‘s hopes to revive the Ottoman Empire. Some of the steps taken toward this end are rather symbolic – the Hagia Sophia was made an active mosque, while others are directly threatening the peace and stability of nearly all the regions formerly struggling under the yoke of the Ottomans – Libya, Greece, Armenia and Syria, where its presence has a destabilizing effect.

This is not the first time that this region and the world find themselves in such a situation. The current state of affairs seems to be a mirror image of the one at the beginning of the past century. Much like now, the world after the First World War was one where uncertainty reigned. While Europe was devastated by the war and was struggling to contain the Spanish Flu, a pandemic much deadlier than COVID-19, the U.S. again chose its policy of isolation[2] and the Russian Empire met its end with the Bolshevik Revolution and the ensuing civil war (1918-1920). All of these events left the world without a true leader who could take upon itself the establishment of long-lasting peace, like the period immediately preceding the First World War, which is known as the Pax Britannica (1815 – 1914).

The observation that Europe could no longer rule the entire world was first made in 1929 by José Ortega y Gasset, in his famous The Revolt of the Masses. The questions he asked then are still relevant now: “Europe no longer rules in the world. Is the full gravity of this diagnosis realized? By it there is announced a displacement of power. In what direction? Who is going to succeed Europe in ruling over the world? But is it so sure that anyone is going to succeed her? And if no one, what then is going to happen?”[3]

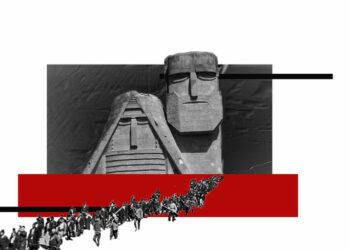

This diagnosis was of course done long after the fact; Europe had already lost its grip over the world in the immediate aftermath of the First World War, and many related issues sprang up prior to 1929. One of those was that Turkey, after committing genocide against Armenians, Greeks and Assyrians, was left unpunished for its crimes during the War. After the end of the Great War, it freely continued its own war with Greece on the west and the newly-created Armenian Republic on the east.[4] Exactly a hundred years after these events, Turkey is again in a conflict with both, actively threatening one and directly intervening on Azerbaijan’s behalf against the other. In the meanwhile, the international community was busy condemning the actions of both belligerent sides and did nothing to stop a war that saw the destruction of Armenian cultural heritage sites and the ethnic cleansing of Armenians.

In the past, the return of Russia, in the form of Soviet Union, to the region stabilized the state of affairs. Today, one cannot see how that is a long-term solution to the problem. Even though Russian peacekeepers are already in Artsakh, and the final negotiations have not started yet, the future of Artsakh and Armenia is rather uncertain. More concerning is the fact that Turkey was again not held to account, even though it has been breaking international laws each time an opportunity presented itself. History repeats itself in a singular manner and we’re witnessing today what it means when a country learns that you can get away with genocide.

One thing that remains to be discussed is the isolationist workings of the great powers. One could debate about a self-imposed isolation, or rather a policy of not meddling, of China and now the United States, which comes as a consequence of what seems to be its decline in global influence. On the other hand, we have the inadvertent isolationist policy of Armenia that has been in development for the past 2.5 years, and stems from the fact that it never developed a new approach and tried to appease both the West and Russia simultaneously, which left both unsatisfied. In hindsight, it should have instead had a carefully thought-out strategy in its foreign policy.[5] As a result, once again, a Russian presence was required to mitigate the differences between two neighboring nations, none of which have had a plan for the peaceful resolution of the conflict. However, a Russian presence, regardless of how long it may last, cannot fully guarantee peace or a final resolution. Just like in the beginning of the 20th century, that presence is yet another sign of a lack of leadership in the world.

Hence, a leaderless world is marching on indefinitely toward a new era, the basis of which is being laid every day by events that fail to find enough recognition, perhaps for the same reason that the world has no leader. What is more, the free world is in a free fall, and perhaps this tragic war and its consequences could be a wake up call for those marching on in their sleep.

also read

A Road Map to Where?

Instead of presenting a detailed plan to help guide the country toward a number of clearly-defined national goals, PM Nikol Pashinyan’s road map resembled a laundry list of necessary post-war actions to take to mitigate the fallout.

Read moreChristianity in Karabakh: Azerbaijani Efforts At Rewriting History Are Not New

In the context of the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict, the “Albanian connection” has become a politicized issue of irredentism, hijacking the rich Christian heritage of Karabakh. The roots of this historiography go back to the Soviet policy of “nativization".

Read moreWar, Nothing But War: The Virtue of Brute Force and the Shortcomings of Diplomacy

The narrow geopolitical framework of the three-decade-old Karabakh conflict is now threatening to become a Eurasian nightmare: Turkey's involvement has sensationalized the war, Iran’s unease has reinforced the confusion, while Russia's perceived passiveness has created much regional anxiety.

Read moreYes, It Is Genocidal

The inclusion of the term genocide is not being loosely thrown around. As the war rages on, the potential for genocide against ethnic Armenians in Artsakh is very real and highly probable, writes Suren Manukyan.

Read more