In rentier states authoritarianism is an addiction, and oil revenues are the narcotic that feeds it. For dictators like Ilham Aliyev of Azerbaijan, oil revenues remain the bloodline through which his oppressive regime sustains itself, and more importantly, oil revenues feed his addiction for aggression and instability in the South Caucasus. While actual addicts suffer from physiological illnesses, dictators like Aliyev suffer the political illness of authoritarianism. This pathological drive for political cruelty, injustice, and casual despotism are the symptoms of a sick political regime. But what will happen when the drug that feeds this addiction is no longer available? What will happen to the Aliyev regime when its oil revenues are depleted and it can no longer feed the sickness of its authoritarianism? In no uncertain terms, it is only a matter of time before it becomes clear to all regional actors and observers that the dictator has no clothes.

The Declining Oil Revenues of the Aliyev Regime

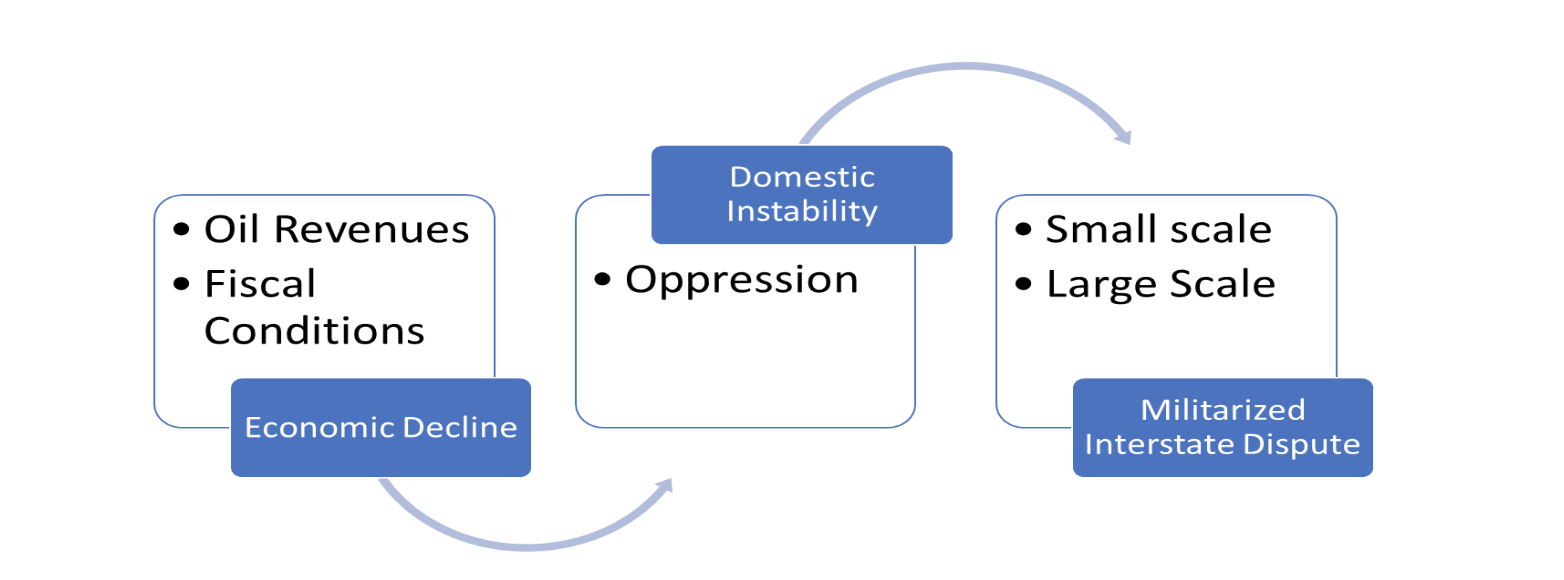

The conflict in Ukraine has increased the global concern over energy resources, and more specifically, Europe’s concern over its energy security. The implications of these developments are of fundamental importance to Armenia, for Azerbaijan’s capacity for militarized interstate disputes (MID) is strongly linked to its GDP and domestic stability. Since oil remains the primary source of revenue for the Aliyev regime, the economics of oil, as well as the political economy of the energy sector, have a direct effect upon the security of Armenia.

As current research and forthcoming articles will display, Azerbaijan’s propensity for violence against Armenia is predicated on economic decline and domestic instability. Noting that Azerbaijan’s economic viability is reliant on oil, and the Aliyev regime’s survival is reliant on oil revenues, disruption with either will trigger an MID initiated by Azerbaijan. In gauging developments for such a high-probability scenario, Armenia must consider the long-term implications of Azerbaijan’s political economy, anticipate disruptions that can result in MIDs interstate disputes, and thus prepare for eventualities by probabilistically predicting Azerbaijan’s behavior. Utilizing data from The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies (which Baku also uses), as well as data and economic forecasting models from the IMF, two important projections are produced: Azerbaijan’s oil economy is not sustainable, and there is a very high probability, in the long-term, of domestic instability in Azerbaijan.

As is generally acknowledged, Azerbaijan’s pipeline projects, including the Southern Gas Corridor, to Europe have been substantially a political project, considering its broader economic limitations and the fact that the intended objectives of the project will not be achieved. As findings demonstrate, the Shah Deniz consortium’s dilemma highlights a very general problem for Azerbaijani producers: while domestic prices are very low, the costs of delivering gas to European markets prove to be too high. Delivering gas from Azerbaijan to Europe is substantially higher than delivering gas from Algeria, Libya, Russia, and Norway. For example, the delivered cost of Azerbaijani gas to Italy is nearly twice the cost of delivering gas from Russia and three times that of delivering from Algeria. With the exception of Azerbaijani gas being competitive in Turkey, it is not competitive in the European market. Forecasting models with respect to the Southern Gas Corridor from Azerbaijan to Europe demonstrate that the high transport costs of the pipeline, and Azerbaijan’s limited gas supply, make this project one of very limited significance for Europe as a whole (with the exception of Turkey and Georgia, as noted). While the project has been politicized by actors in Brussels and Baku, analysts conclude that the commercial conditions for the Southern Corridor’s success have actually deteriorated as political support for it has grown. Namely, the political discourse and the promotion of the Southern Gas Corridor has become more akin to a public relations project, as opposed to one with substantive economic outcomes. Quantified results demonstrate that, by 2030, Azerbaijan’s delivery of oil will remain an insubstantial contributor to Europe’s energy balance. More to the point, experts note that there are no plausible scenarios under which the transport infrastructure expansion will be completed in this decade, a direct confirmation that the set objectives of the project will not be attained.

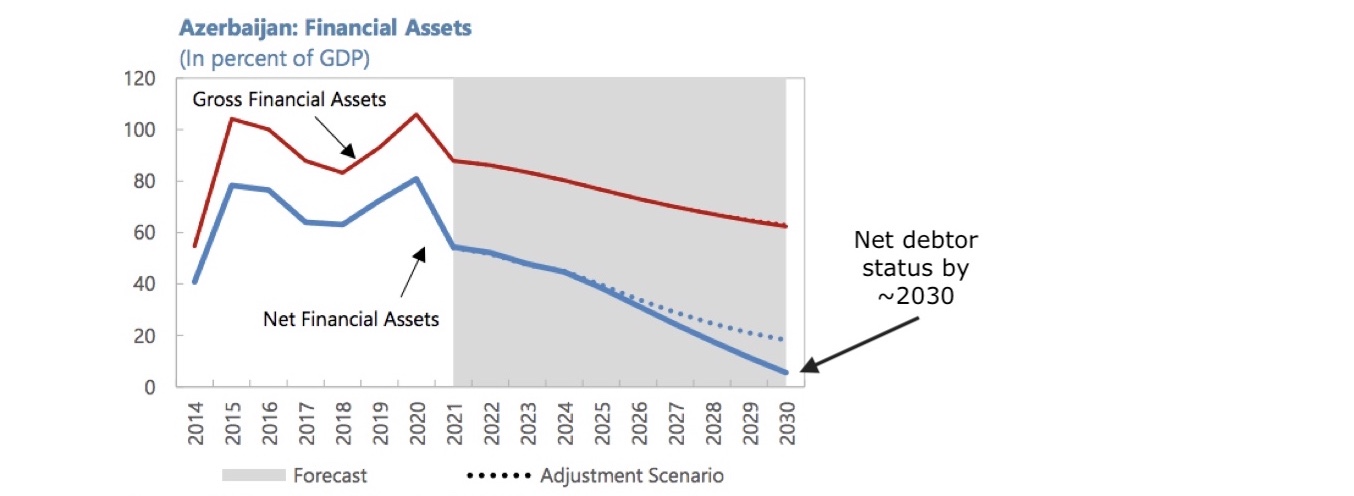

The IMF’s calculations also confirm these projections. IMF affirms that continuing decline in oil production is projected to lead to Azerbaijan becoming a net debtor nation by 2030. The IMF specifically notes (and Baku concedes) that Azerbaijan’s net financial assets will decline to zero by 2030 as oil output from the main BP Azeri-Chirag-Guneshli field also declines towards zero. The exponential decrease in assets is displayed in the chart below, as 40% decrease is projected by 2030.

Source: National authorities and IMF staff calculations and estimates.

Note: Baseline scenario assumes the nonoil primary balance increases in average by about 1pp per year during 2022-30.

Adjustment scenario assumes the nonoil primary balance increases on average by about 1.5ppper year dyring 2022-30.

Thus, with the deterioration of oil revenues, the IMF projects that Azerbaijan will face significant deterioration in its fiscal conditions. Since Azerbaijan has not saved its oil revenues to mitigate for the transition to a post-oil future, its state expenditure remains primarily reliant on oil revenues. As these revenues diminish, its oil-dependent economy remains exceedingly vulnerable to an economic crisis. As a decade of deep trend analysis attests, domestic crises in Azerbaijan generally trigger MIDs against Armenia. While such a crisis has an eight year trajectory, Armenia must prepare for this eventuality, considering the exponential declines that will be observed in Azerbaijan’s economic conditions.

A continuous axiom within rentier states, and specifically with those that have very little economic diversification, is the relationship between economic decline and domestic instability. In this context, the dangers of Azerbaijan’s economic decline to Armenia is the high probability of domestic instability within Azerbaijan. Concurrently, as research shows, domestic repression is correlated with MIDs. And since the Aliyev regime profoundly relies on oil revenues to maintain power, an inevitable decline in oil revenues correlates with inevitable domestic instability. Both developments, when quantified as causal variables, indicate the increased probability and likelihood of Azerbaijan initiating hostilities against Armenia should such developments take place.

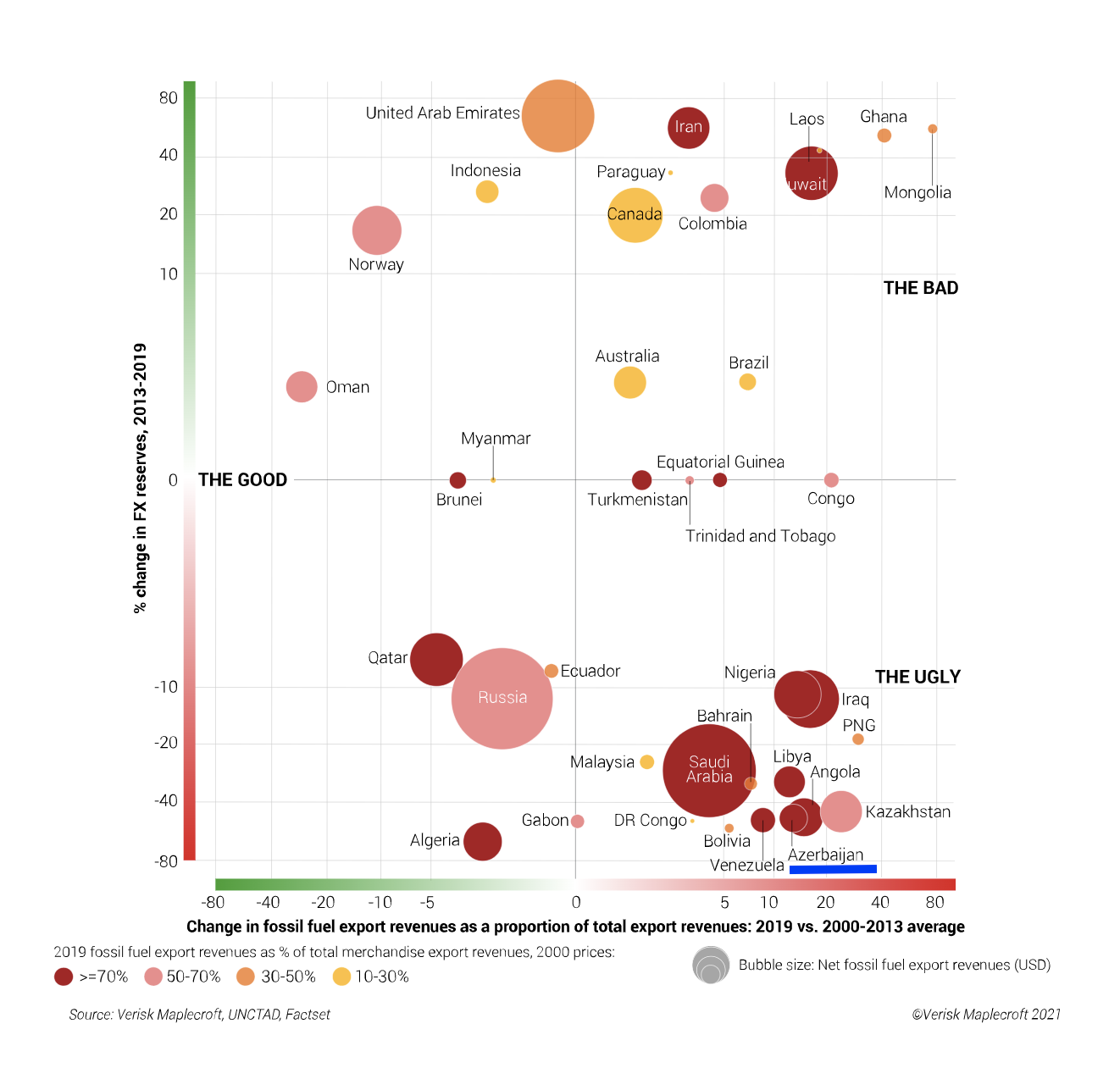

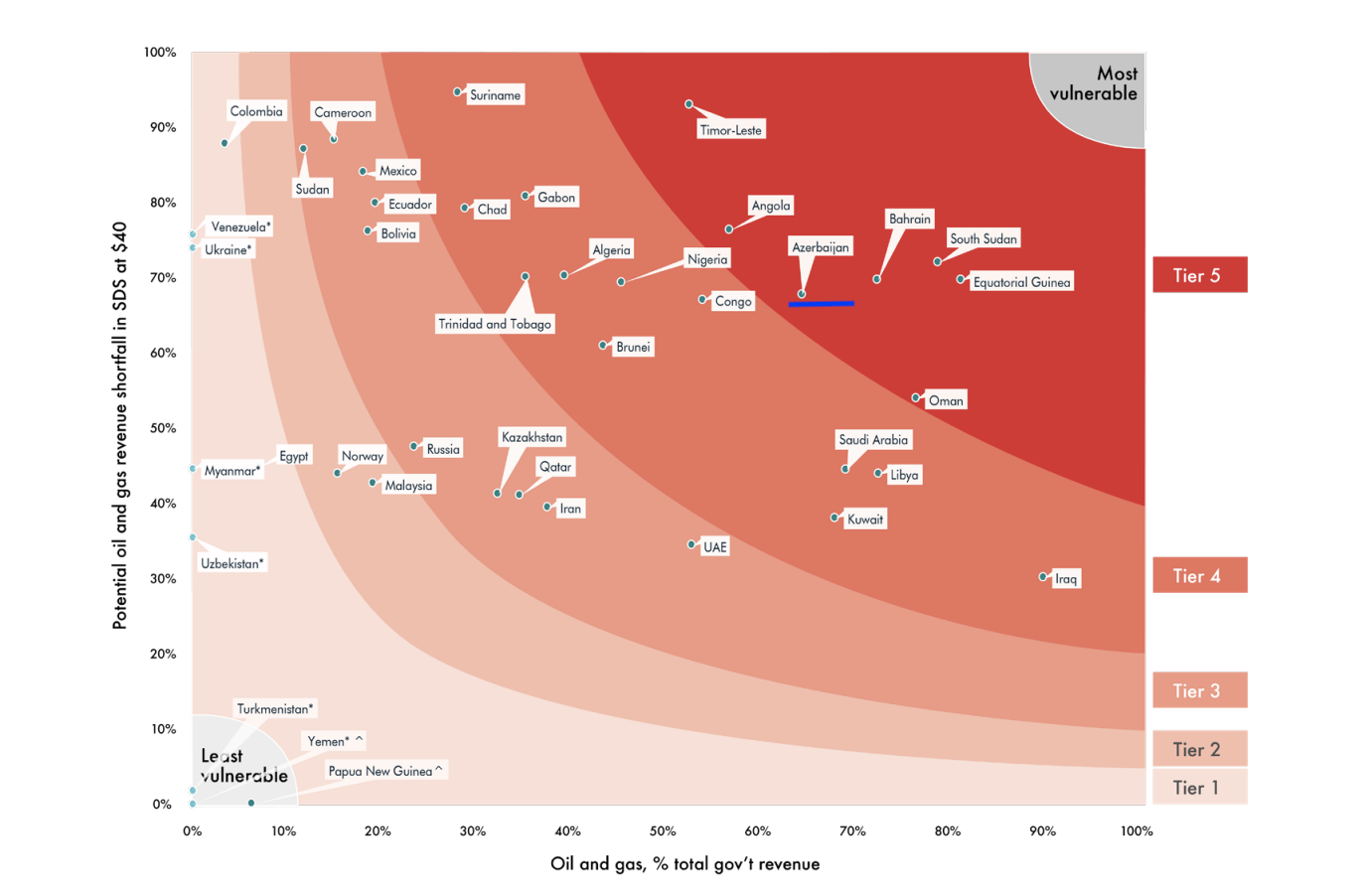

When lagging the data by a decade and mapping it comparatively, the findings confirm the severe limitations of Azerbaijan’s economy, thus supporting broader projection modeling into 2030. The chart below, for example, demonstrates the dismal state of Azerbaijan’s oil economy. The chart frames Azerbaijan’s oil-reliant economy and lack of diversification within the broader context of oil-producing countries. The lack of diversification, and the over-reliance on oil for state expenditure, places Azerbaijan at the bottom tier of oil-producing countries. This is consistent with the IMF’s conclusion that the external position of Azerbaijan’s economy is substantially weaker than the levels consistent with medium-term fundamentals. When aligning the net assets of the country reaching zero by 2030 with the “ugly” state of its oil-dependent economy, the economic indicators point to a pending financial crisis, which in turn, reinforce our findings on domestic instability. In this context, Armenia must be cognizant of the consequences these developments are going to have on Azerbaijan’s behavior and the high-probability of Baku initiating MIDs.

The macro concerns with Azerbaijan’s oil-economy also expose Baku to immense vulnerability. The chart below demonstrates the high level of vulnerability that Azerbaijan suffers from with respect to its economy’s over-reliance on oil and gas. Azerbaijan is ranked as one of the most vulnerable petrostates in the world, as it suffers from a projected 70% risk of vulnerability if there are shortfalls to its oil and gas revenues. And as The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies and IMF’s findings and projections demonstrate, shortfalls are inevitable by 2030. In this context, Azerbaijan becomes extremely vulnerable to economic shocks, and by extension, domestic shocks by 2030.

Vulnerability of Petrostates’ Total Government Revenues to Low Oil and Gas Demand in the Energy Transition

Source: Rystad Energy, IEA, IMF, SSB (Norway), CBL (Libya), CBI (Iran), UN, CTI analysis Notes: Vulnerability = potential total government revenue shortfall [multiplication of axes] over 2021-2040. Tiers roughly equate to a shortfall of <5% (1), <10% (2), <20% (3), <40% (4), >40% (5) of total revenue. Potential revenue shortfall = 2021-2040 average in SDS vs 2015-2019 average. Shares on x-axis are 2015-2018 average due to lack of 2019 data. * No government-reported data for Turkmenistan, Venezuela, Uzbekistan, Ukraine, Yemen, Myanmar (plotted at 0% on x-axis).

Azerbaijan’s Pending Instability

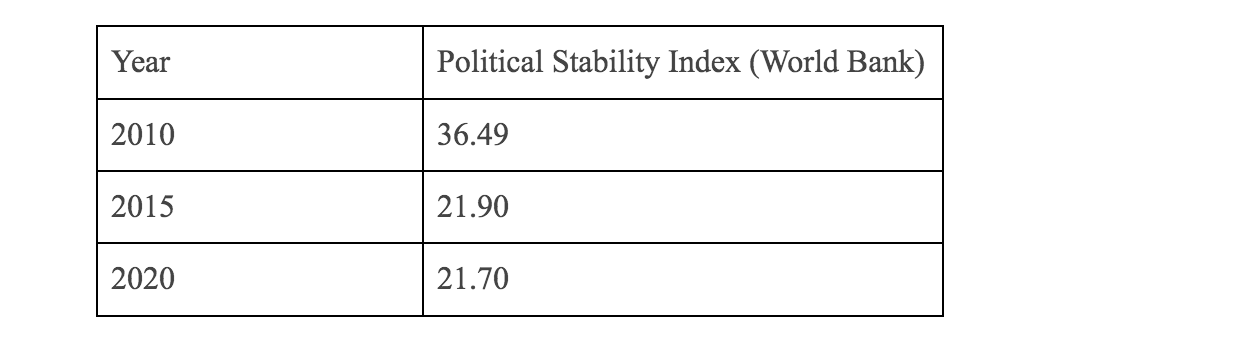

When observing trends with respect to Azerbaijan’s domestic stability index, we find that the more repressive the Aliyev regime has become, the more unstable the country’s political stability ranking has shifted. As the chart below demonstrates, Azerbaijan’s political instability has increased exponentially in the last decade (lower number in the index indicates increased instability). The levels of repression were comparatively lower at the start of the decade, as Aliyev was beginning to consolidate his authoritarian regime. But as his consolidation of authoritarianism increased, so did the levels of repression. However, levels of repression did not translate into stability, but rather, it has had the inverse effect. As the index displays, by 2015 Azerbaijan had become a lot more unstable when compared to 2010, and as Aliyev fully consolidated his rule and became more ruthless, the stability index has also demonstrated a decline.

Thus, while oil revenues, spending, and GDP growth have, overall, been relatively stable, this has not contributed to political stability. Rather, it has translated into an increase in the political instability indicators. When aligning these indicators with the degree of the economy’s vulnerability, as well as lack of diversification and over-reliance on oil for expenditure, all projections suggest high probability for domestic instability and challenges to the Aliyev regime within the next 10 years.

An important component of Armenia’s long-term contingency planning must substantively consider the high probability of domestic instability in Azerbaijan, and the consequences that this will have upon the Aliyev regime’s behavior towards Armenia. As the numerous empirical findings demonstrate, the causal and correlative relationships between economic decline, resource depletion, decline in oil revenues, and domestic instability and oppression all trigger some form of an MID against Armenia.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Considering the totality of these findings, Armenia must account for five important trends:

- Fluctuations in levels and degrees of public unrest in Azerbaijan must serve as predictive variables in gauging risk-propensity for Azerbaijani militarized action against Armenia.

- Fluctuations in levels and degrees of public oppression by the Aliyev regime must serve as predictive measures in gauging the probability of imminent militarized action against Armenia.

- Armenia must anticipate domestic unrest and instability in Azerbaijan within the next 10 years, and must anticipate both defensive as well as offensive options in order to capitalize on the upheaval taking place in Azerbaijan.

- Strategic contingency plans must be developed to incorporate pre-emptive diplomatic initiatives to raise international awareness of both Azerbaijan’s brutal suppression of its own people as well as pending and imminent militarized action against Armenia.

- Strategic contingency plans must be developed in conjunction with Armenia’s Armed Forces to formulate pre-emptive military operations, enhanced security protocols, and intensification of hybrid warfare during periods of upheaval and instability within Azerbaijan.

The Aliyev regime’s facade of building a strong state, a strong economy, and a strong future remain just that: a facade reminiscent of an addict seeking validation to continue one’s unhealthy ways. Its illness of authoritarianism is not only an endless threat against Armenia, but also a perpetual state of repression, cruelty, and suffering for the Azerbaijani people. Hatred of the Armenian is not going to make life better in Azerbaijan, and as things get worse for the regime, their only resort will be to enhance this collective hatred to conceal the failures of authoritarianism. The fulcrum of the regime’s diversionary tactics rest on villainizing and scapegoating Armenia, with the singular objective of pulling a veil over the Azerbaijani people and obstructing them from seeing the obvious: the dictator has no clothes. The sooner Armenia realizes this, the sooner Armenia prepares for this, and the sooner Armenia exposes this, the sooner it will establish the configurations for a post-Aliyev South Caucasus.

Indeed, this topic (the decline of Azeri oil) has been an open secret for some time now. Chevron, a formerly major Azeri oil consortium member, completely exited Azerbaijan in 2019, seeing few prospects; Exxon-Mobil continues to look for buyers for its stakes, all of which leaves second-tier oil producers in country. Production peaked in 2008, 14 years ago; oil output is now, at best, half of peak, and declining steadily at an industry-familiar rate of between 5 and 15% per year. One can look at BP’s public annual reports from the early 2000s, which remarkably accurately forecast this production profile and the coming exhaustion of viable Azerbaijan oil (would encourage those interested to do so). (There are minor adjustments, such as BP’s upcoming Azeri Central East platform, but these at best will yield only very minor readjustments of the decline rate.)

Limited exploration for new oil has also repeatedly failed– eg most recently, just this month, the heavily promoted Shallow water Absheron Peninsula prospect was abandoned by BP after finding no viable oil. Oil majors have largely moved on from the Caspian, to South America and Africa and elsewhere. Azerbaijan’s natural gas, as the author notes, despite public proclamations, falls far short of addressing any of the government’s fiscal shortfalls– natural gas has brought in only about one-tenth of the revenue of oil for Baku, and the gas pipeline infrastructure in Azerbaijan and Turkey still holds tens of billions of dollars of construction debt. It’s only today’s elevated hydrocarbon prices that mask the Azeri fields’ declines. In an economy in which oil and gas are 90%+ of all exports (the #2 export of Azerbaijan is tomatoes), the consequences can not be overstated.

In the Azeri case, the coming decline is not a matter of ‘if’, but a matter of ‘when’ and ‘how fast’. The world has seen this movie before. The (only?) question is whether Azerbaijan’s path will look more like Angola or Venezuela, or Libya or even Syria.

Incidentally, economic dislocation in these cases (grievously undiversified, corrupt petrostates) will likely come earlier than otherwise expected– in Azerbaijan’s case, one tripwire is that the currency has been artificially pegged to the US dollar since the 2015 manat collapse. This peg will likely be the first casualty of oil revenue depletion (compare with the uncontrolled depreciations in 2015; since then, the manat is already 30% or so overvalued even when compared to, for example, similar petrostates such as Kazakhstan). It’s often when currencies collapse, and populations feel abrupt, acute pain, that governments collapse or are brought down.