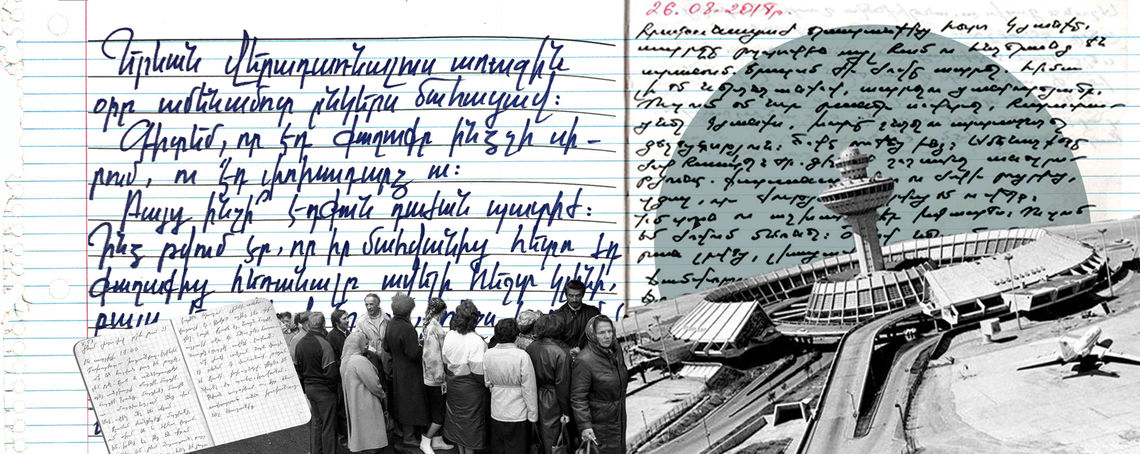

There was a time, back in the early 1990s when there were only two flights from Yerevan’s Zvartnots International Airport. One was to the capital of Russia, Moscow, the second to another Russian city, Sverdlovsk (currently Yekaterinburg). People would pay pilots on the runway for the freedom to whisk them away to their dreams, away from starvation, away from Armenia. The war with Azerbaijan over Nagorno Karabakh, the blockade by both Azerbaijan and neighbouring Turkey, the collapse of the long-standing social system of the Soviet Union and the economic crisis in the early 90s forced many to leave their cities, their country and each other.

This process that started at the end of the last century has been going on for about 30 years now. During the third decade of independence, before the Velvet Revolution in the spring of 2018, people sought and found different ways to leave because of the lawlessness and social injustice in Armenia. Instead of jumping over the walls of Zvartnots and boarding the plane from the runway, people have received scholarships, married foreigners, illegally travelled to Europe and sought asylum in Western European states.

Statistical services promptly publish the numbers of those leaving Armenia, those arriving and those who do not arrive. Behind each number in these reports, there are personal stories and feelings that remain undocumented and unaccounted for. People continue to leave. On the path to their departure, some of them put down in their diaries the emotions that are not meant for reports.

In Yerevan, a city where even the walls have ears, people have prefered to tell their stories to their diaries. Despite their sometimes overwhelmingly personal nature, we have been able to collect about a dozen diaries that document the very personal feelings hidden behind the TV-reported numbers of those leaving Armenia.

This number accounts for approximately 1.3 million people, over the past 27 years, who have left the country forever.

Two of them, a young family with a newborn child, in the absence of electricity and hope, under the pressure of the ongoing war, packed their suitcases in the spring of 1994. Loreta, 21 and her husband, Karen, 23, shouldering the huge responsibility of parenthood, bought two tickets to nowhere and left the country. So did many others. During her pregnancy and the first years of their life on the move, Loreta wrote a diary about the first stages of her child, Aren’s life. A life which immediately after being started was meant to be packed up for another country.

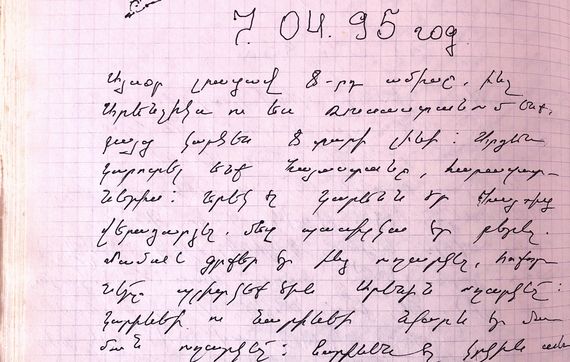

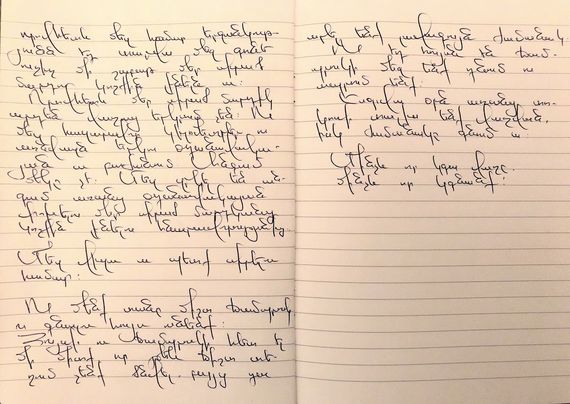

Assumed to be a temporary migration, it became a life stamp for the coming decades of their lives. This is where our journey begins: in-between Zvartnots and different transit airports. After eight months of searching for a new life, in the southern Russian city of Samara, Loreta, wrote in her diary about her longing for Armenia.

Aren and I have been in Russia for eight months now, but it seems like eight years. We already miss Armenia and my relatives. Karen returned from Armenia yesterday and brought us a care package. Mom had sent me books, and the aunts had sent chocolate bars for our child.

Although now there are multiple flights from Zvartnoyts, instead of the two to Russia, the country which has been the main destination for Armenian migrants since the country gained independence after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Armenia is the fourth migration “donor’’ of Russia. Officially, only during 2019, more than 165,000 Armenian labor migrants have been registered in the country. It is almost twice more than the number of Armenians working in Russia in 2012.

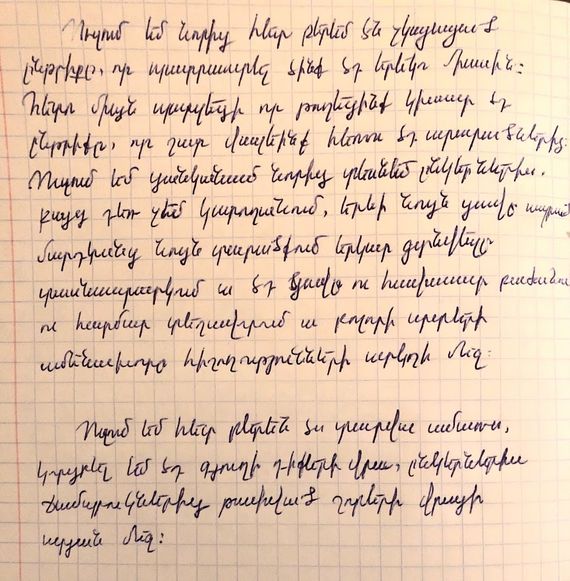

Loreta’s diary.

…because for us, happiness is being near the person we love for at least a week in a year.

Because the people we love are not in our country any more. And we are separated by thousands of kilometres and at least two airports. Not even one. We have been deprived of the opportunity to be near the people we love without changing an airport or two.

We need a visa in order to love.

So we always keep a suitcase at home and hope to leave. Together with hope and the suitcase, we also think that even though we weren’t born in the right place, we were born at the best of times. So we put the hope in the suitcase and live on. We lend today to tomorrow without interest, and time flows.

Until tomorrow, until we leave.

The author’s notes from the airport.

When they say “Yerevan,” I imagine the road to the airport, broken memories, and broken lives equivalent to the value of an air ticket. I know that you will go; you are too good for all this. I have never imagined you living here. I always imagine you with me, having a coffee, smoking, and talking about my unrequited loves. But no worries, we can do all that in another country. You go in peace, love, and I will follow. I will come to the airport, I won’t hear of it, but no, I will not cry, and that’s quite possible, so please don’t laugh. Do you remember how we used to walk around Yerevan, how we used to roam every corner just to be able to talk to each other, to listen to each other? You are like my mother, but a girlfriend-mother. My mother is my mom only, she is not my girlfriend, while you are my first and only girlfriend-mother. When I do stupid things, you listen to all the details keenly and with a laugh, and then you offer advice with your strict voice and tell me not to regret anything.

Oh, how we fought to find our place. I remember the words “no point” an awful lot. We used to say, “there’s no point” all the time. Do you know when you left? Two weeks before the revolution. I remember I first felt that I loved Yerevan on the day of Serzhik’s resignation. I was crying, and those weren’t happy tears. A woman asked why I was crying, and I said: “I wish my best friend would see this.” I was sad because standing in front of Ilik, I felt love for Yerevan for the first time, but I was alone, and you didn’t feel that love.That love was the type that passes quickly, but doesn’t fret, sister. I know that my place is where we can have coffee together, laugh loudly and cry the same way. That place is not Yerevan, sister. I said goodbye to my father in Yerevan and never saw him again.

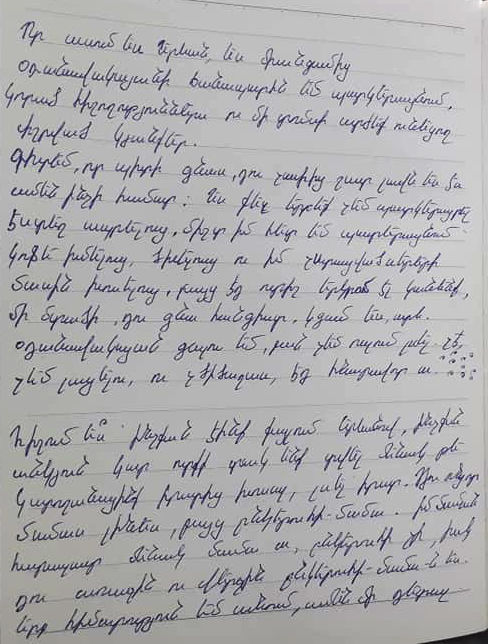

Inessa’s diary.

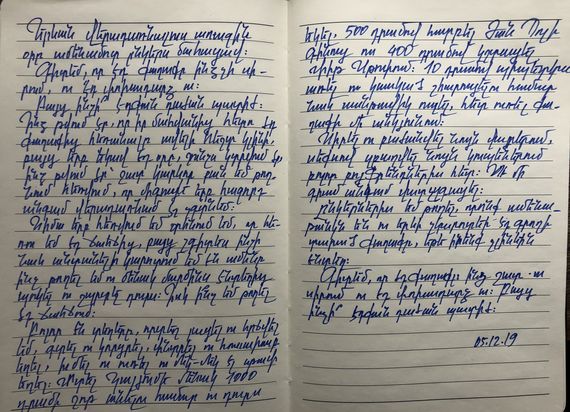

According to statistics published in November 2019, the number of those wishing to leave Armenia after the revolution dropped by about 30 percent. Many already have hope for a prosperous future in their own country. Nevertheless, people continue to leave Armenia. Opportunities for a decent education, better jobs lead people to take the path to foreign lands. And Inesa did too. Recently, she moved to a small town in northern Italy to work for European Solidarity Corps.

In rented homes in Yerevan, people bid farewell to their friends and then to the city as Hermine, 24, and her husband did. An opportunity took the young couple to Europe in 2019. There they were able to not only receive a better education but to have more social freedom, afford things they would not have been capable of in the most ‘’conservative and aggressive’’ society of Armenia. On a dark night, before her flight, she bid farewell to Yerevan, her neighbour, and her love of the city.

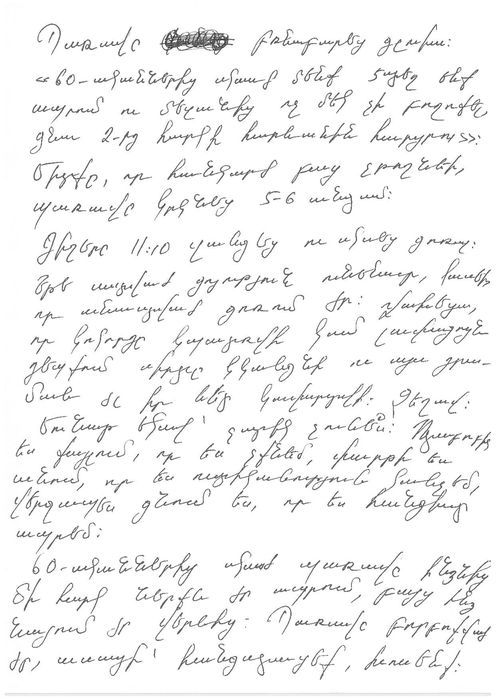

The old lady was messing with my head. “We have been living here since the 1960s and no one has ever complained about us; you can ask the second-floor neighbour.” The old lady repeated the same sentence 5-6 times. She called me at 11:10 p.m. and started yelling. If God did exist, I would say that those were ungodly screams. I was scared that she would tear her throat or that her heart would stop, and this entire drama would come to an end. But it did not happen. She bitched at me: “Don’t you have slippers? You are walking barefoot to keep me awake. You are having parties so that I call the police. When will you finally leave so that I can live in peace?” The old lady had been living on the floor below since the 1960s, but she looked down on me. She was irritated, so I told her to calm down so that we could speak.

She said: “I’m calm, I’m in my home, it is you who is not calm.” The old lady lived on the floor below, but she looked down on me because I was a lower species: I was renting the apartment. And she was a sophisticated whore who yelled at me for 15 minutes on end that I did not own a house or a pair of slippers, and I walked barefoot to disturb her peace. After I switched off the phone, my friends said forget about her, she is toxic, and that’s what she wanted, to poison you, your mood, and your world. “She’s just an old lady who needs to talk.” And then my friends kept insisting and pressuring me – forget about it right now, don’t think, don’t think, drink up the wine so that you forget. I became even tenser. And then I recalled that during a party another friend of mine had vomited on the newly renovated balcony of the old lady and the old lady had called the police. So I calmed down a little.

And then we went to the city center to dally and to walk around nocturnal Yerevan for the last time before I left Armenia. My friends were happy; I was trying to be. It was raining. I realized that 1 a.m. is not for sleeping, but rather for loving Yerevan at that exact moment, when there is no one around and you can walk fast, even barefoot, if it hadn’t been raining, and the old lady would not yell, “Where are your slippers? WHERE are your slippers? Why are you barefoot?”

Inessa’s diary.

Thousands of kilometres away, in the capital city of Denmark, what makes Hermine think in ambiguity about the future in her homeland, is a dream for Hayk, a 24-year-old sociologist. The prospect of getting a quality education in Scandinavia and cultural exchange keeps him on the road as well. The optimism on the Norwegian airline’s bag “In a while you will be fine,” still keeps Hayk and many others in the country. In fact, Hayk, like many young male scholars of his age was not allowed to leave the country for a while. Military service is a two-year-long obligation for every male citizen of Armenia. For the young talented professional, life awaits between opening and closing of university application deadlines and waiting for an email.

On the other hand, with constant news about deaths on the Armenian-Azerbaijani border and within the Armenian armed forces, obligatory military service is another reason why many families leave the country. Some parents prefer to take their sons overseas so they can escape the obligation.

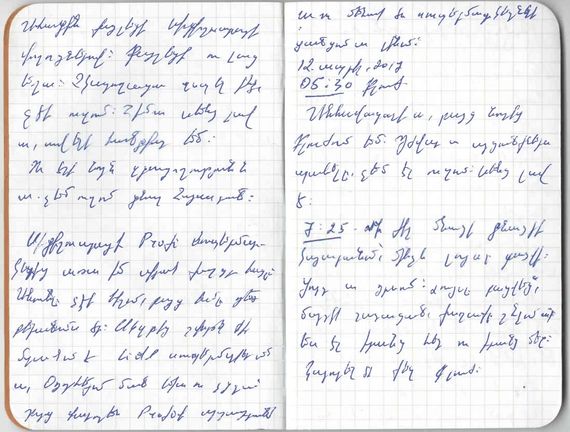

Hayk’s diary.

I have missed a large part in the sky of Bucharest, Istanbul and left it without notes. I’m going back to Armenia, but one thing is certain: I will be coming back.

I walked along the streets a lot. I walked and I cried. I couldn’t help it, and I didn’t want to. It’s better now, I’m calmer. And I have the same feeling: I do not want to go back to Armenia.

… I bought my favourite sweet bread from the supermarket. I couldn’t remember the name, but the taste was still on my tongue.

05:30, April 12, 2017, Cluj

It’s unbelievable but I’m in Cluj again. It’s hard to hold back my tears and I don’t even want to. This is better.

07:25 I stayed in the train station until sunrise. It’s cold outside. The sun rose, the people came out, and the town started breathing. So did I, together with them and inside them. I missed you, Cluj.

07:53 I think I’ll go and walk around the town.

Arthur’s diary.

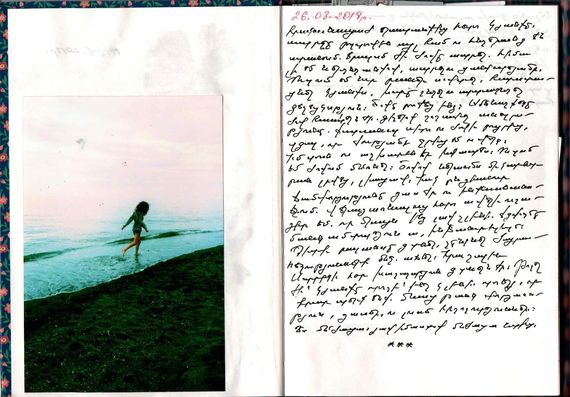

Life has an entirely new flavor after your dreams have come true. I used to dream about living by the sea. Now I am filled with inspiration and lust for life. I want to learn new things to enrich my life, to breath in deep and to breath out beauty. The sparkling endlessness of the sea at night was the most beautiful thing. To freeze from the scent of the sea, to feel that my essence is made of water. This was indeed my home and my world. I want to die in the sea.

But apart from achievements, the roads of departure are also places to reconsider memories of loss. Sometimes the routes outlined do not take people to their destinations. Discrimination and intolerance force many to pack up and leave the country indefinitely in the hope of a decent life. Ironically, the majority of Armenian society considers both migration and people from the LGBTQ community as a ‘’threat to the national security of Armenia’.’

Ananumos diary.

I want to bring back the supper we did not have, the one we had prepared that evening together. I learned later that we left the supper halfway through to enjoy it far from those creatures. I want to miss my friends, but I cannot, not yet. Perhaps the existence of the people who suffered from the same pain in the same territory for a long time multiplies the pain and then distributes it equally among them and places it in the box of the deepest memories in their hearts.

I want to bring back the summer of this year which I lost on the slopes of the village, in the blood on the clothes that spilled from my friends’ suitcases.

The lives of these all people become a pattern where after living for a while overseas, they can not get used to the quality of life and conservative perceptions by Armenian society. So these lives are lives of eternal search for cheap flights tickets. These people are going to leave the country but still miss it when they are away.

On the first day back in Yerevan, one of my closest friends died. I know that the city does not love me and that is reciprocal. But why such cruel punishment? I felt like that after his death, leaving the city would be easier, but when the day has come, I can’t breathe. I thought I am leaving something very important behind, which will not be found on my next return.

Now, when I am far away, I am blessed that I am far from that swamp. But unclear why I am unbearably missing everything I left there and took only my body and threw myself out. But what have I left in that swamp?

All the places, where I cried and felt excitement, found and lost, searched and disappointed, drank and smoked, sometimes have been sober. Went to Calumet, just to drink a shot for 1000 drams, got drunk by the wine in Jean Paul, ate in Pit Stop with 400 drams. Bought pipette for 10 drams and not to cause suspicion also asked for a Santavik, then smoked in a corner of the city.

I loved and broke up in the same places, had sex in the same ‘’coupes’’ with my all boyfriends and have never felt bad for that. I left my friends, who are the most valuable. Perhaps I would not have missed the cursed city if they were not there. I know, the city loves me very much, and that is reciprocal. But why is this punishment so cruel?

05.12.19