The main thing about people are their eyes and their feet. One should be able to see the world and go towards it.

Alfred Döblin, Berlin Alexanderplatz[1]

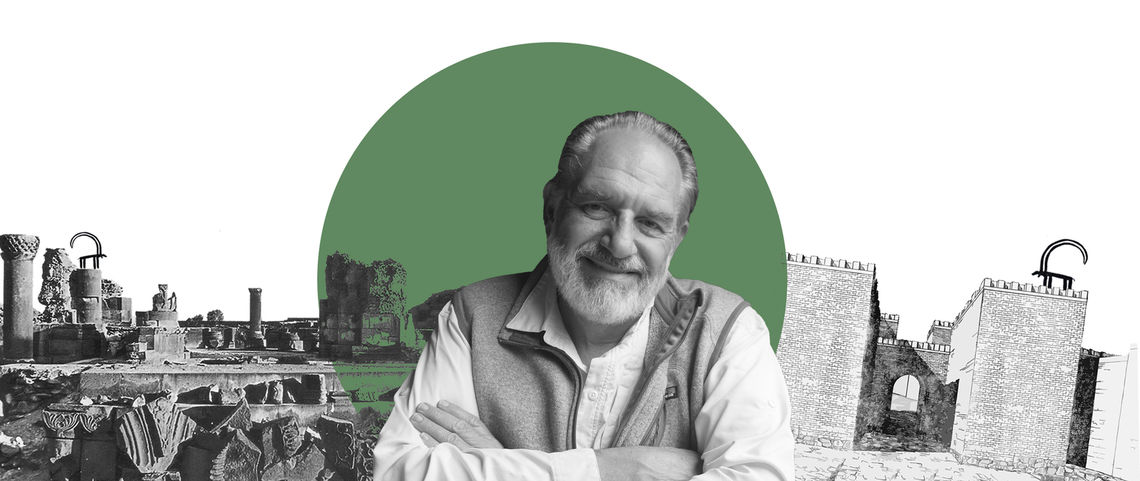

It was 5 p.m. on Sunday, August 2, 2020 when I received the news of Professor Gregory Areshian’s passing. To say that it was a shock would be putting it mildly, even though I knew that he had been hospitalized with COVID-19 a few weeks earlier. I had received a last phone call from him a week before; he told me that he just wanted to hear my voice. Now I know that it was a farewell.

In describing his life and his extraordinary career, it is hard to choose where to begin. To speak about him in earnest, I have to go as far back as Urartu, for he was a larger than life figure, whose thinking encompassed everything from the dawn of the Ancient Near Eastern civilizations down to our own days. Having said this, it may be advisable to start with his first encounters with history and archaeology, as this was the period where his precocious mind was shaped.

He was born on May 13, 1949, in Yerevan. He developed a fascination with history when he was only a five-year-old child. He read voraciously about the history of warfare, which later paved the way for his interest in archaeology. The latter bond was solidified by a family friend and renowned archaeologist Boris Piotrovsky, who was conducting excavations at Karmir Blur (Red Hill, in Armenian) at the time. Later, Piotrovsky would become Areshian’s supervisor and mentor at the University of St. Petersburg. Areshian often told his class stories about Piotrovsky; the great reverence with which he addressed his mentor exposed the indelible impact that he left on the development of Areshian’s worldview.

In the early 1970s, Areshian worked at Karmir Blur himself and this marked the period where he became acquainted with the works of American archaeologists who viewed archaeology in relation to anthropology. His approach to archaeological excavations was shaped during the work he undertook at Karmir Blur, where he became firmly convinced that archaeology alone was not enough to fully understand the complex societal relations of the past. As his student, I had the chance to see the master at work in the summer of 2018, in Sisian, where he hypothesized possible explanations for the erection of Zorats Karer merely by looking at the site. He also told me how important it is to write and theorize about everything we see or find during actual excavations. For him, excavations were only part of a wider process and should not overshadow the other components.

From the early 1970s to the end of the 1980s, his career as a scholar went from strength to strength. At 26, he was the youngest person to graduate with a PhD from the Institute of Archaeology of the National Academy of Sciences of the USSR in St. Petersburg. He became an associate professor of archaeology at Yerevan State University. He partook and conducted various excavations in the Ararat plain and Masis Blur from 1985 to 1990, as well as being a visiting scholar during the German Archaeological Institute’s excavations in Egypt in 1990. The end of the 1980s and the turn of a new decade were politically turbulent years, and Gregory Areshian was an active participant in the formation of the new Republic of Armenia. He first joined the government as Deputy Prime Minister and then later became the President of the National Science Foundation. In 1993, he was forced to leave Armenia, an event which he considered as pivotal in his life, as it set the start to his outstanding academic career in the United States.

During the 22 years that Areshian spent in the US, he taught at 14 different universities and colleges, including the University of Chicago and UCLA, where he came to become the Assistant Director and an associate researcher at the Cotsen Institute of Archaeology. In 2008, he also conducted excavations at the Areni-1 cave [in Armenia], which led to the discovery of the 5,500-year-old shoe, and brought great renown to his already-established academic authority. In 2013, his edited volume on the multidisciplinary examination of empires was published by the Cotsen Press. As part of the Cotsen Institute, he also conducted excavations at Masis Blur, along with Pavel Avetisyan, starting from 2012.

In 2015, he started teaching at the American University of Armenia (AUA), leaving behind a long and successful academic career in the United States, and that is where I first met and got to know him. Soon after having completed his course “Study of History,” with his help and encouragement, I embarked on my journey of becoming a historian and was lucky enough to be called his friend.

For his outstanding work in the field of Middle Eastern archaeology and history, a Festschrift honoring Areshian was published by the University of Oxford in 2017, titled Bridging Times and Spaces: Papers in Ancient Near Eastern, Mediterranean and Armenian Studies.

Apart from all his field work in Armenia and elsewhere, he also had a major contribution in shaping the view of young students, being a proponent of the theory that Armenian history should be studied and can only be understood in the context of world history—a thesis so often talked about and yet so rarely followed.

During his years at AUA, Areshian became increasingly interested in the affairs of modern history and political science, connecting and explaining everything with the approach of his favorite historian Fernand Braudel. It was this worldview, imbued with the longue-durée approach of Braudel, that he imparted to me and to all his other students.

This view also reinstated his initial interest in history and archaeology, which in his own words was to understand “How can major socio-cultural changes be causally explained from interactions of individual historical events.” These individual historical events, according to Areshian, found their full realization only in the historical longue-durée. Even though Areshian never hid his interest in European history, especially that of medieval Italy and the later Renaissance, he always stressed that his primary field of interest and expertise is the civilizations and cultures of the Ancient Near East, which he felt shaped every other civilization that followed in their wake.

An incident that showcases his remarkable approach to history also explains his view of life. During one of his classes, while talking about the creation of the first written signs, cuneiforms, Areshian praised the ingenious minds of the ancient Sumerians who ascribed this creation to diplomacy rather than to account keeping, which is factually true. This comes to show that Gregory Areshian never had a dry or merely factual outlook on life, which is the case with many in the profession. To him, it was important to use one’s imagination, and in this sense, he was a living example that history is about our life as it is or as it can be and not only a dry narrative of times long passed.

It is therefore essential to mention how important it was to him that those around him, his students and friends, remained attached to the world around us. The lines by Alfred Döblin, “One should be able to see the world and go towards it,” perfectly summarize his worldview, which never lost its connection with reality and the world despite constantly evolving and reaching new heights. That is his legacy that we should feel obliged to continue.

—————–

1. Alfred Döblin, Berlin Alexanderplatz Die Geschichte vom Franz Biberkopf, Suhrkamp Verlag, 1980, p. 28.

2. Y. H. Grekyan & P. S. Avetisyan (Eds.), Bridging Times and Spaces: On Pathways Taken and Not Taken: Between Archaeology, History and Interdisciplinarity, Archaeopress, 2017, p. vi.

also read

Samvel Karapetyan’s Éclats de Voix and Armenian Cultural Heritage

The late Samvel Karapetyan's work goes beyond Armenian heritage: It is a luminous testimony that highlights the violence of certain states to annihilate an indigenous culture with impunity.

Read moreThe Reluctant Artist: A Tribute to Herman Avakian

Curator and art historian Vigen Galstyan pays tribute to one of Armenia’s most accomplished artists, photographer Herman Avakian, who passed away suddenly on Sunday. With his uncompromising devotion to the truth and artistry, Avakian helped shape the fabric of Armenian society.

Read more