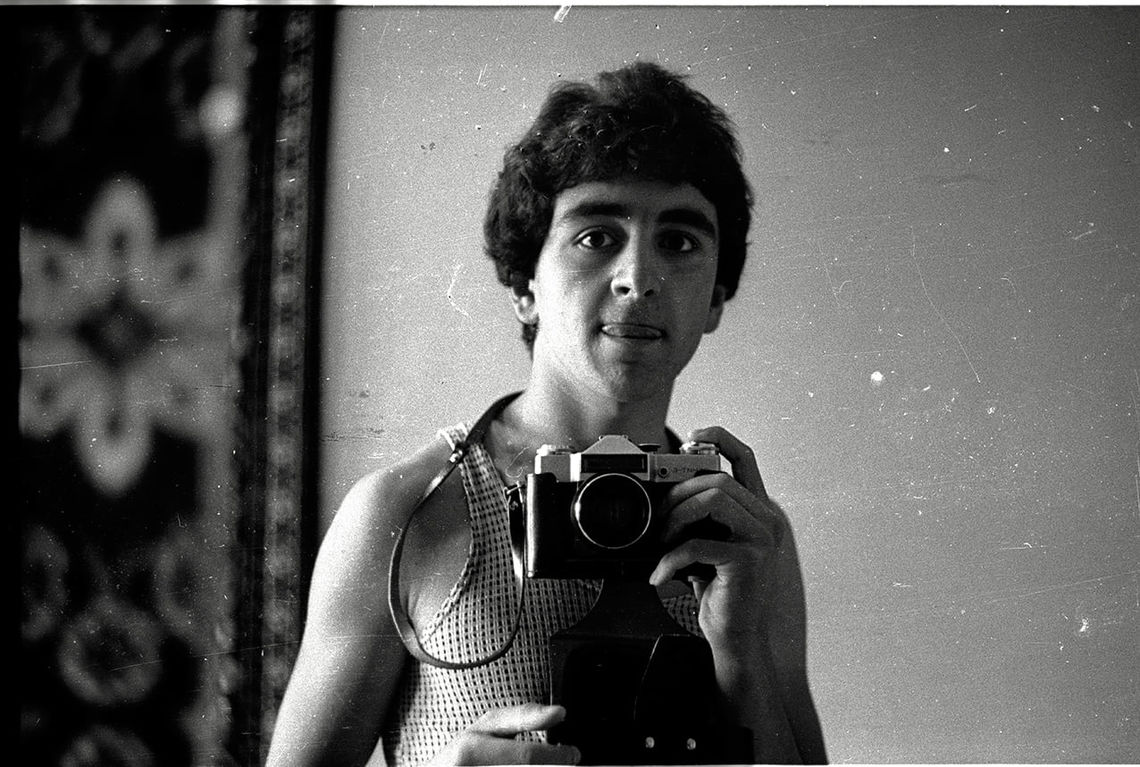

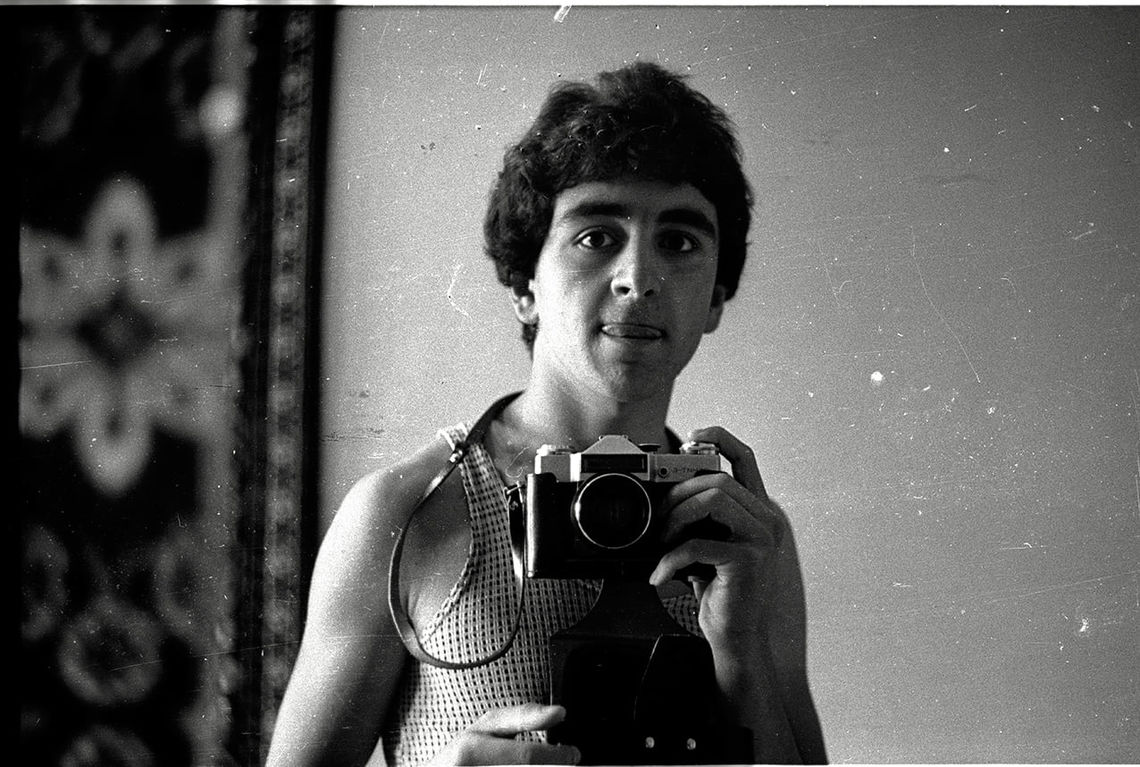

Herman Avakian, first self portrait, 1980. Copyright, Herman Avakian.

Some months ago, I received an irritable message from Herman Avakian, complaining about the “incompleteness” of a short profile article I wrote on him for the Database of Armenian Photo-Media Practitioners. Taken aback by this sudden and unfounded reprimand, I sent him an equally barbed response. We had known each other since 2005 and had a very congenial relationship, but I still felt that talking to Herman was like walking on a tightrope – a wrong word and he might cut you out of his life forever. Fortunately, we managed to avoid a skirmish, and a few days later I found out through a mutual friend that the message was a ruse to provoke me into contact. Wanting to discuss a project, he wasn’t sure that I’d pay attention if he just wrote “nicely.” When he passed away this Sunday from a sudden heart attack, the effect was so shocking that, for a moment, I thought it to be just another one of his mischievous pranks.

As friends and colleagues are trying to process this devastating news, a particular sentiment seems to be shared by everyone: Yerevan, and Armenian photography certainly, is not going to be the same without him. Because Herman was not simply a major documentarian and artist – he was part of the city’s fabric and one of the personalities that gave this place its inimitable character. Though his brash and combustive behavior could often lead to quarrels, there were few who didn’t admire his uncompromising devotion to the truth and ethical practice. But the force of Avakian’s personality, its largess and deep contradictions, often tended to overshadow the scale and impact of his work. While his untimely passing will be an irreplaceable absence, the process of appreciating the true importance of Avakian’s photographic legacy is yet to begin.

Born in a small Georgian town of Tsulukidze (now Khonia) and having spent his childhood in Germany, Avakian ended up in Yerevan in 1980 to study engineering. He had already developed a passion for the camera (a good way of attracting the attention of girls, he once told me), which quickly overshadowed any other career plans. As an active member of the “Yerevan” photo-club, Avakian connected with most of the professionals in the field, including masters such as Gagik Harutyunyan and Vahan Kochar, who became key role models. He was also drawn into the artistic avant-garde, which would soon transform Armenia’s cultural sphere with ground-breaking exhibitions held by the Third Floor Union and other collectives.

One of these renegade figures – the conceptual artist Grigor Khachatryan – became a life-long friend and offered the photographer his major breakthrough. Khachatryan served as the art director of “Garoun,” arguably the most influential literary-critical periodical in Soviet Armenia since the 1960s. The journal had revolutionized perceptions of photography in Armenia by divesting it from narrative content and stressing the significance of the photograph as an autonomous artistic medium. But Khachatryan aimed to go further and pushed for photography that was not merely “artistic,” but also politically provocative: a bullet shot at the reader’s eyes. He found the perfect collaborator in Avakian, who rose to the task with feverish aplomb. Between 1987 and 1994, the magazine’s pages became filled with dramatically “outré” content: from a phallic-looking thumbs up, surrealist eggshells to male nudes bound with rope. It was a short, but breathtaking period of experimentation, which coincided with the cataclysmic events that put Armenia on an agonizing transition to independence, filled with disaster, war, emigration, but also utopic dreams for the future.

Though he did do some reportage during this early stage of his career, Avakian preferred to address the upheavals of these times indirectly. Namely, he shot metaphorical images full of anxiety that were focused more on the uncertainty of the future than on current events. Broken objects, shadows, empty buildings, dark passageways, distorted faces and barriers of all kinds form the crust of these eerie photographs. They show a young practitioner enthralled by the medium’s ability to transform the recognizable reality into something otherworldly and full of hidden signs. What they also testify to, is Avakian’s great desire to be taken seriously as an artist. This was not an easy task. Despite the involvement of many photographers in the art scene, the medium was still seen in Armenia as something that could either document contemporary art, or be used in it as raw material – rather than stand there in its own right. And yet, few artworks made in Armenia in the late 1980s encapsulate the era more precisely than Avakian’s photograph of a fence on a beach with a figure’s split shadow falling through it. A condensed expression of the desire for escape, it is an image that evokes the exodus of over a million Armenians in the following three decades – people who would leave their homeland, families and identities, for more “promising shores” overseas. Avakian himself lived in the U.S. for a while, but eventually returned home, refusing to be splintered between different countries and cultures. Years later, he would jokingly dismiss these early works as pretentious attempts at “art photography” that had none of the validity of the classical documentary approach.

With the demise of the USSR, the entire infrastructure supporting professional photography in Armenia also collapsed. Thus, as a freelancer, Avakian was forced to take on reportage work and commercial assignments. Never without a camera around his neck, he seemed to be constantly on the beat, much like his beloved idol of street reportage – the American poet of the underworld, Weegee. This was a deceptive impression, however, since Avakian always preferred to conceptualize and explore a particular issue as a thematic project developed over time. The epitome of this approach was his 1998-2002 series about the Vardenis mental asylum. Shot with merciless immediacy, the unsparing horror of these black and white photographs exposed the kind of institutional cruelty that Armenians were never accustomed to seeing applied to their own culture. As a wake-up call for a desensitized society exhausted by war and political conflict, the project sparked public outrage, prompting a government inquiry into this macabre “sanctuary.” The experience also brought Avakian considerable international attention and strengthened his belief in the ability of documentary photography to affect social change. It was an important stance that was crucial for the development of the next generation of Armenian documentary photographers, for whom Avakian served as a vital role model and facilitator.

For much of his career thereafter, Avakian focused on topics that he thought were being ignored by the wider society. Refusing to chase bombastic topics, he photographed people affected by the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, disappearing rural communities, minority groups and civil movements. As he searched for the most direct means of communication, his photographs became aesthetically plainer and blunter. For him, the challenge was to articulate his message with a single – and fully comprehensible – image that didn’t burden the viewer with unnecessary content. This required prolonged reflection and care, which is why Avakian mostly abandoned field reportage in favor of extensive thematic series.

One of his life-long interests was the world of artists and writers, whom the photographer documented throughout his entire career. He seemed happiest when collaborating with friends, such as Sahak Poghosyan, Grigor Khachatryan, Onnig Kardash and many others, and we owe Avakian an immense debt for leaving us an extensive and unique archive of Armenia’s artistic milieu from the past four decades. This work showed not only his deep respect for the intellectual process but also his unabated faith in art’s ability to find answers for life’s paradoxes. Though, in his late years, Avakian dismissed the label “artist” in regards to himself, this is certainly what he strived with his own work. That is also why he remained a stalwart of analogue photography and continued to make gelatin silver prints even when the general public had become accustomed to seeing photographs solely on their device screens. Exasperated with the rise in media manipulation and lack of image literacy, he aggressively attacked breaches of copyright and could mercilessly critique any of his colleagues who had failed his strict standards of photographic ethics. To him, photography was something that was meant to raise hard questions, and not make people comfortable in their delusions. Needless to say, he derided anyone who thought otherwise.

Always full of ideas that he was in a rush to execute, Avakian’s last project was dedicated to his close friend and associate – the late documentary photographer Ruben Mangasaryan, who was also prematurely taken away by heart failure, in 2009. Shooting on expired 35mm rolls left in Mangasaryan’s studio, Avakian photographed disconnected bits and pieces over the past year: ruins from Gyumri, cemeteries, fragments of statues and traces in natural landscape. When he staged the show a few months ago, it was in his typically eccentric fashion. Exhibited for a single day only, the disparate images coalesced into a hauntingly poetic vision of decay, absence and the promise of rebirth. It was a return to his roots in “subjective” or art photography, but looking back at it today, the exhibition has acquired a much more chilling connotation. More than a tribute to his lost friend, it is like an overview of Avakian’s achievements in photography – a summation of his ideas and findings about the medium’s relationship to reality and time. Great artists seem to anticipate their own death, as they say, and Avakian’s last project only reaffirms this notion. His departure leaves us not only with the duty of perpetuating his invaluable oeuvre, but also cementing its unassailable place in the annals of contemporary Armenian art and photography.