The Armenian government has recently attempted to reconfigure the country’s educational system, with the stated goal of increasing efficiency and enhancing quality. While this is a noble effort, the government has proposed to merge post-secondary educational institutions without giving any clear reasoning as to how or why it will work. This new initiative involves the merger of Brusov State University with the Armenian State Pedagogical University and the Armenian State Institute of Physical Culture and Sport. So far there has not been any quantified analysis proposing what the process could look like, which is leading many to question the benefits of the transformation.

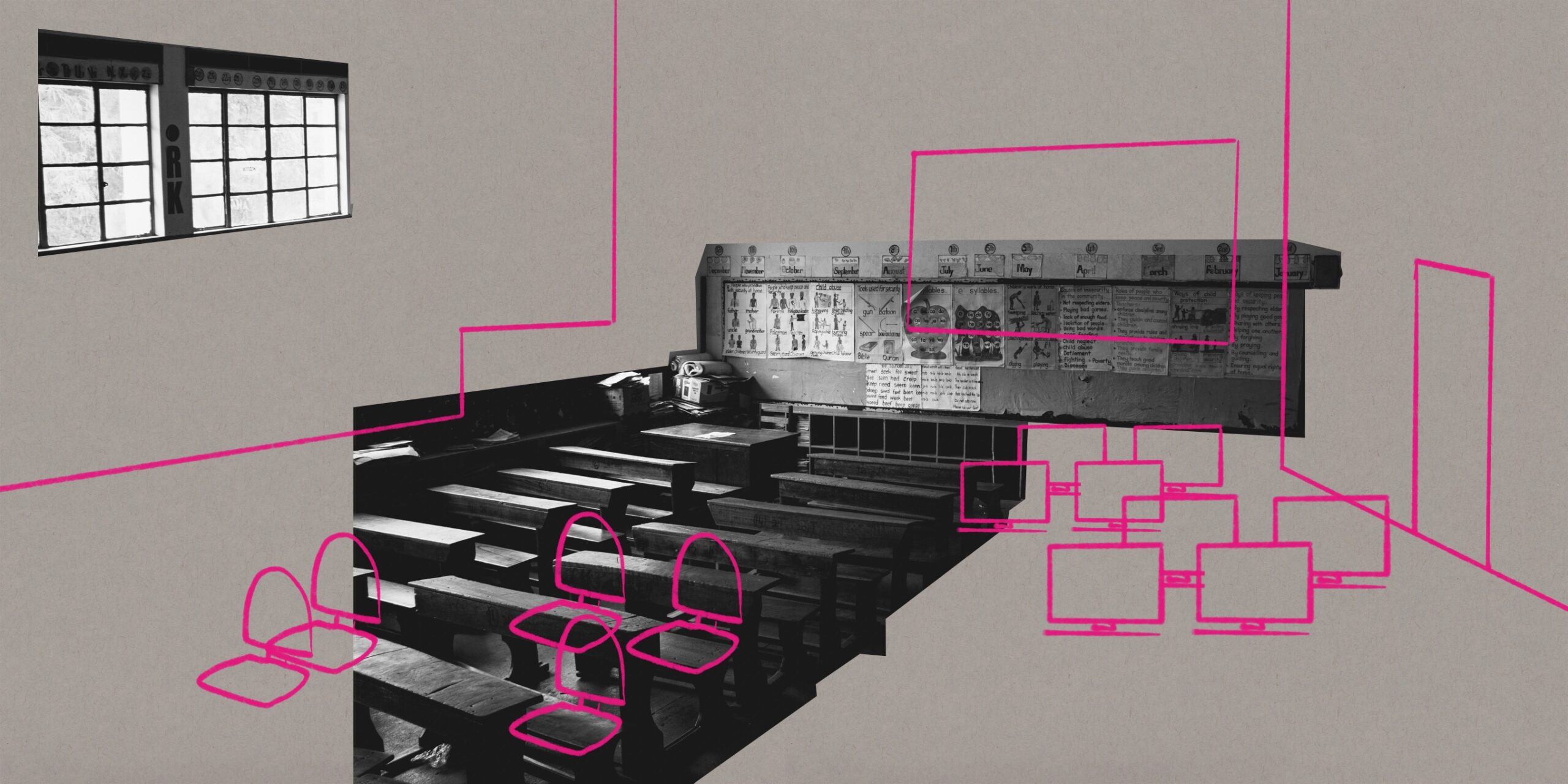

The educational system in Armenia is, in many ways, outdated, and modernization is necessary. Armenia’s educational, scientific and cultural renaissance during the early Soviet period was instituted by decree and financed by the imperial center. Armenia and many other Soviet republics benefited from the centralized Soviet policy regarding education. In the case of Armenia, a vital influx of repatriates from educational and cultural centers abroad (St. Petersburg, Tbilisi, the Middle East, etc.) made progress even more striking. However, in today’s world, centralized education is no longer a system conducive to higher education. Centralized education still exists in places like China where the political structure and the government finance and manage the scientific and educational sphere. Thousands of students are sent to study abroad to fill the deficit of highly educated professionals in many domestic spheres. The Chinese government has also started hiring foreigners to teach at their universities.

Armenia simply does not have the same resources and political system as China to send students to study abroad and return or hire foreign professionals. Students leave Armenia to study abroad using their own resources, often never returning. In Armenia the Ministry of Science, Education, Sport, and Culture (MSESC) is in charge of many diverse and unrelated fields. The Ministry governs that structure in the outdated model of the Soviet Union. This is totally ineffective, and counter-productive in the current political and economic climate.

The rest of the developed world has been steadily approaching and resolving practically every issue from an economic point of view. While commercializing science and culture is far from ideal, Armenia would have a long way to go before it reaches a level where it becomes a problem. In the current climate, capitalizing the educational system is the best approach to improving the situation. The government can set up oversight agencies (similar to the National Science Foundation in the U.S. or the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnologia in Latin countries) instead of having the ministry and the minister directing educational, academic or cultural institutions. These agencies should be in charge of the distribution of finances. How finances will be dispersed should be based on a competitive process of selecting projects by independent review committees and not by ministerial decree. The projects will have oversight and revision to develop in an orderly manner without financial abuse and deviations.

Such an agency for science exists in Armenia, called the Science Committee, however, its functions are diluted by operating in parallel with the MSESC and in conjunction with the National Academy of Sciences. Many educational and cultural institutions can be profitable, which will simplify the problem of financing and reduce government interference establishing proper evaluation and assessment.

Educational institutions have a potential to be self-solvent financially. Their activities, including independent development of curricula, should be decided solely by their own governing bodies. Furthermore, they should have a certain degree of autonomy, regardless of being state funded institutions. The disadvantage of a centralized system can curtail and undermine academic freedom and a one-size fits all approach that can impede the education process. The governing body and administration of the university can apply for federal financing, thoroughly justifying their proposals. Once funding is secured, it is their duty and responsibility to know how to spend it properly. The university’s governing body and a scientific council should have the autonomy to decide if it is appropriate to open a new department, research center, or merge with another institution. I work at Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico, the “Autonoma” in the name means that neither the government nor the police have the authority to operate on the university premises or interfere with its operations.

On the other hand, the mentioned university is a behemoth, a monopoly in terms of state financing that dominates the entire 100 million population of Mexico. The university hampers competition with its vertical “socialist” governing system, making it ineffective, sometimes corrupt, and slow. The dominant universities in developed countries achieve their status not by uneven state financing but by their academic record and private donations. The tendency is to create, maintain and develop as many centers as possible. As an astronomer, I have seen hundreds of astronomical departments in private, public, and even liberal arts colleges in the U.S. and the UK. All of them compete, collaborate, and develop in their own way, ensuring diversity and deeming it an essential component to creativity and progress. Student exchange programs are offered to different educational levels and provide ample employment opportunities. The abundance of options provides freedom for faculty and researchers, who can choose the subject of their study and seek financing and career advancement. Confining everyone to the same, one and only university is detrimental to progress. The relatively small but no less influential country of the Netherlands has at least four world-renowned astronomical centers at the universities of Amsterdam, Groningen, Leiden and Nijmegen.

Armenia needs to diversify its educational system if it hopes to move its position forward in the world. Institutes and universities providing similar education should be found throughout the country, and not just in Yerevan. They should strive to be self-sufficient but receive support from the state. University salaries should be favorable enough to encourage professors from abroad to come and teach in Armenian educational institutions. The jobs at the entry level positions should not be tenured to ensure rotation and fluidity of academic staff. The governing bodies should dedicate themselves to fostering a just and fair distribution of finances, assessments, and quality control. This would include independent professional review of proposals, allocation of funds to the winning project and oversight of the execution of the project. The position of a Soviet-style minister should be removed and replaced with a secretary or director, who manages and allocates the funding to projects approved by independent reviewers and not as someone who will decide repertoires of theaters or the composition of a university’s departments. A method of evaluation should be created based on international experience and best practices and decisions should be based on assessments, programs and analysis, not the whims or desires of every new minister.

Also see

Armenia’s Relationship With the Humanities and Social Sciences

While innovation is increasingly being acknowledged as key to a country’s competitiveness in global markets, contributions of the humanities and social sciences to the body of knowledge are largely left out of debates.

Read moreArmenian Attitudes Toward Science and the Soviet Legacy

Armenia’s scientific sector was decimated in the 1990s. Many in the country have been talking about its former glory for 30 years with pride, anger and longing. What were the priorities of Armenian science during the Soviet years and what is its potential today?

Read moreWomen, Paper and Power in the Medieval Period

A historical retrospective of the social realities and perceptions of the legal status of women in the Middle Ages, specifically in the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia.

Read more