Innovation is increasingly being acknowledged as key to a country’s competitiveness in global markets as well as in the ability to address urgent social, security, and economic problems. Traditionally, science and technology research were seen as central to innovation in both scientific and broader public circles. This view, however, misses out on the fact that innovation does not happen in isolation, but rather requires a vast range of actors, cooperation, and diversity of ideas. The contributions that humanities and social sciences can make to the body of knowledge and innovation are largely left out of debates.

The range of human experience, thoughts, identity, and expression that the humanities and social sciences help us understand is crucial as it nourishes a nation’s cultural existence and national identity, inspiring creative behavior.

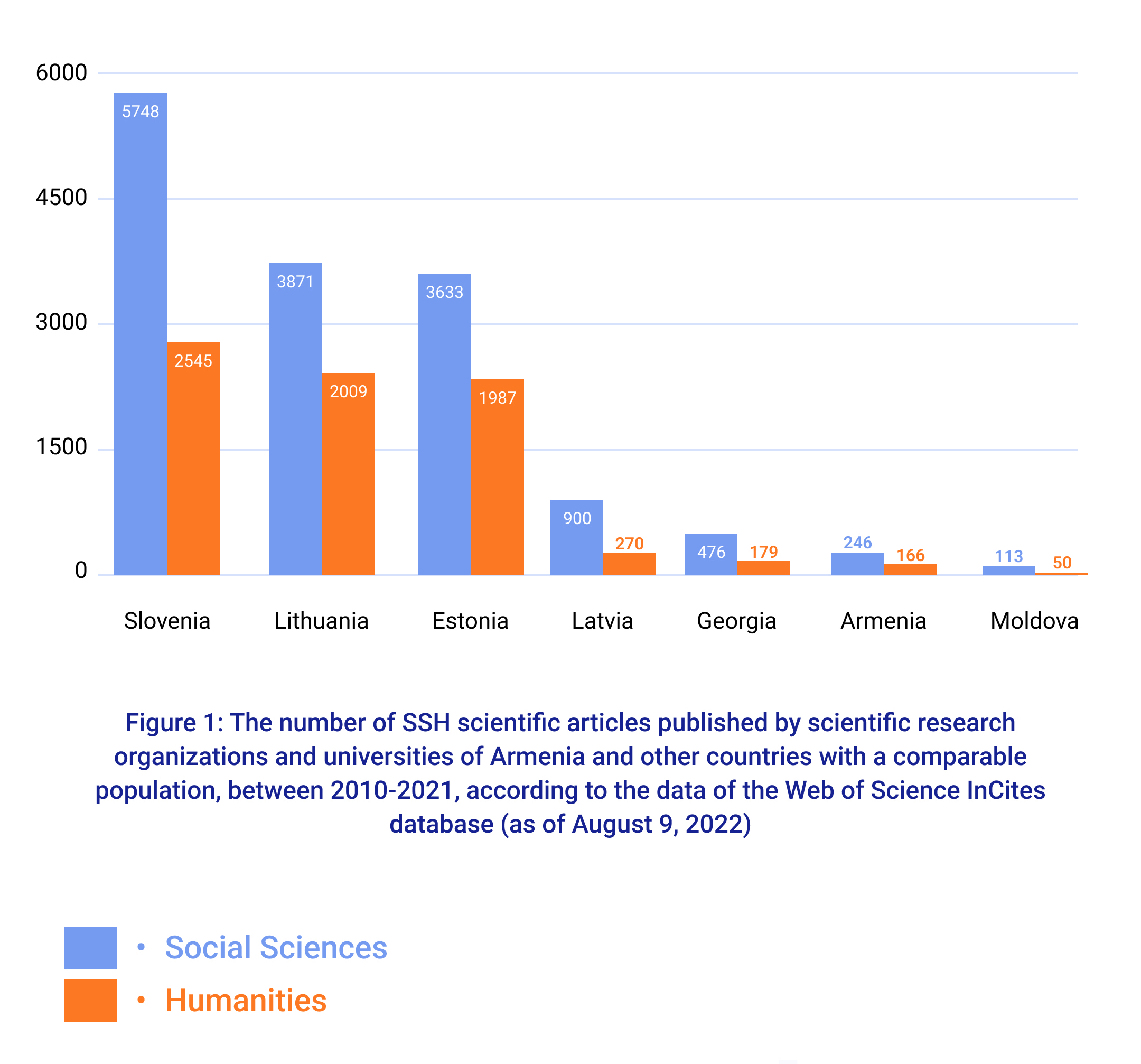

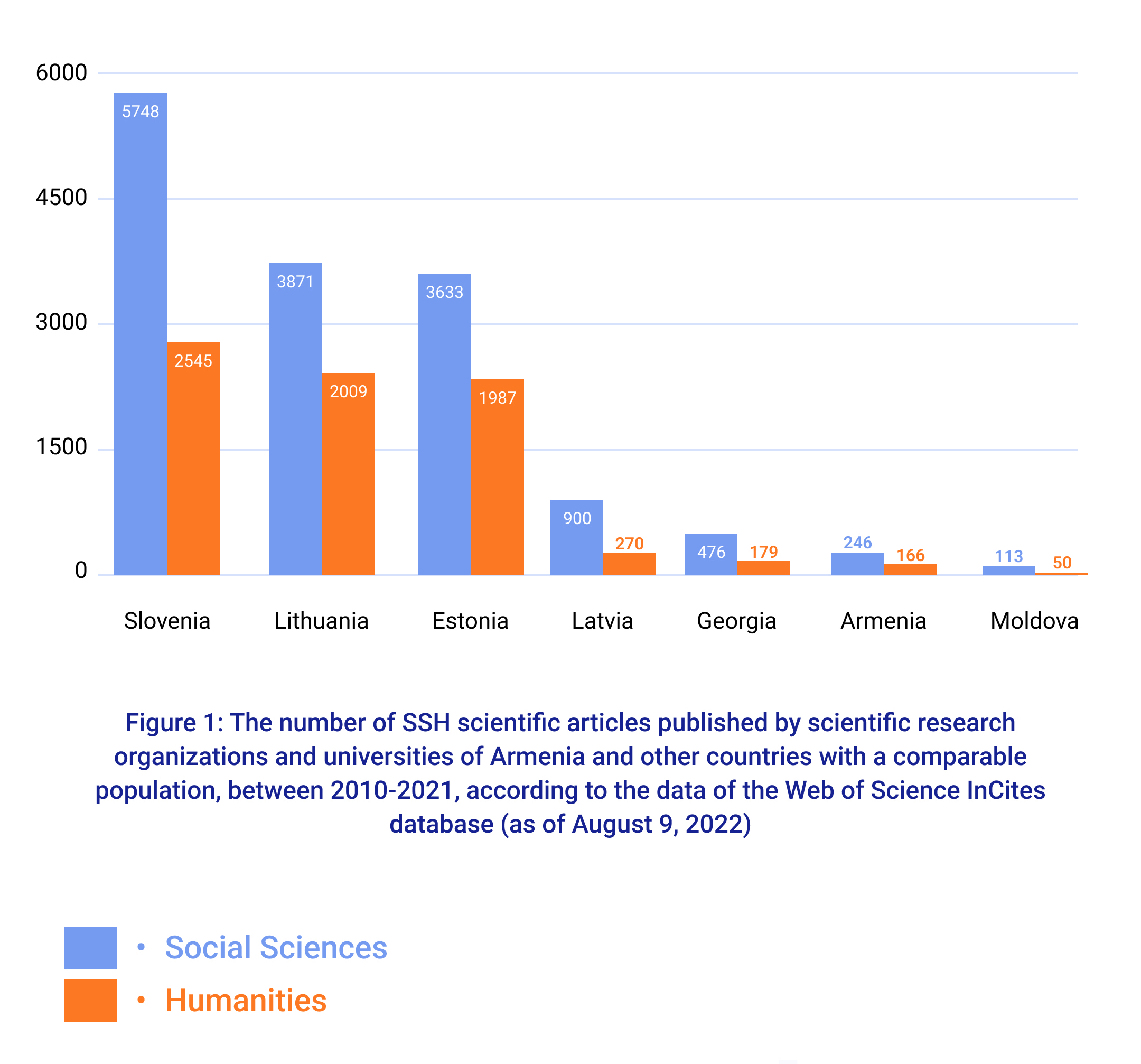

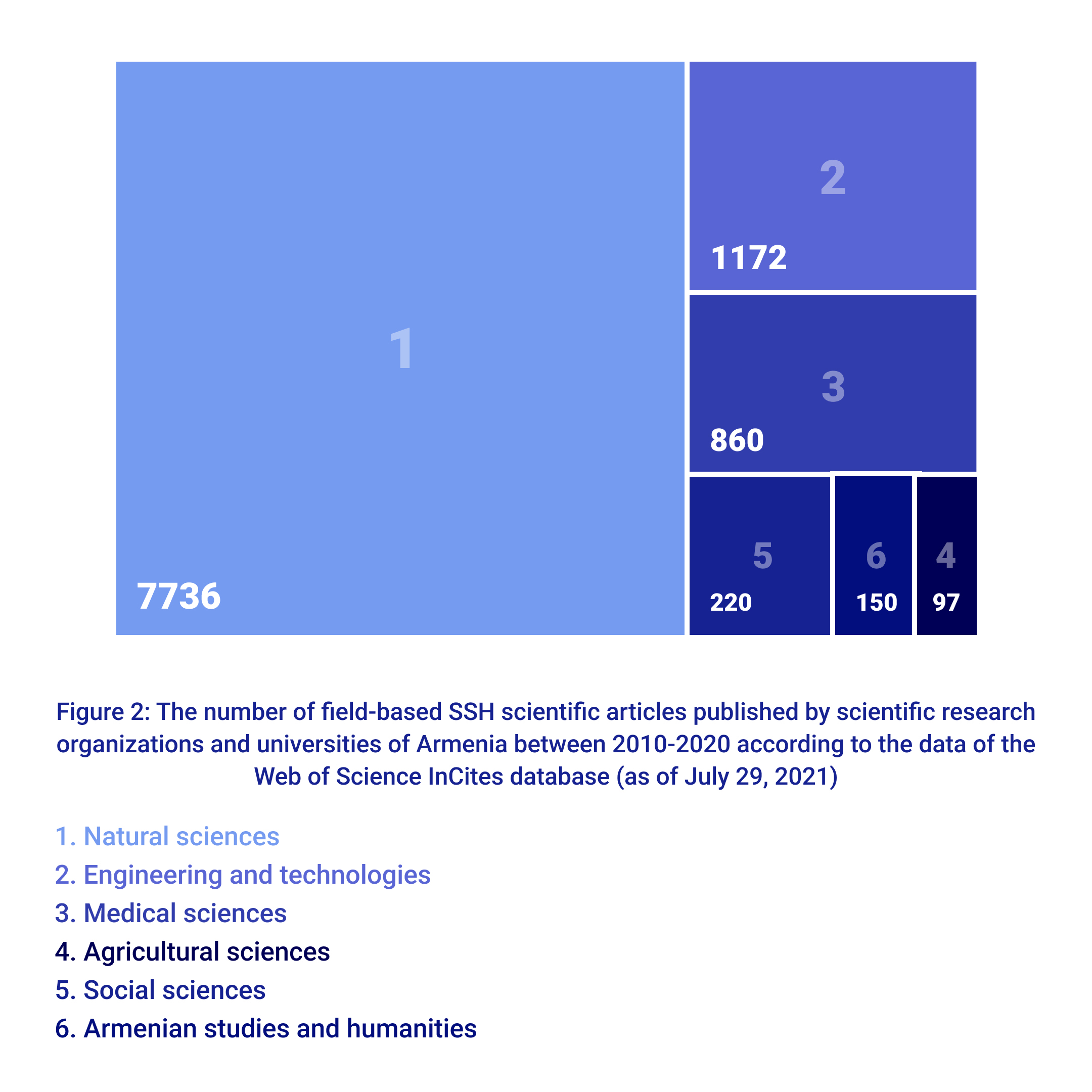

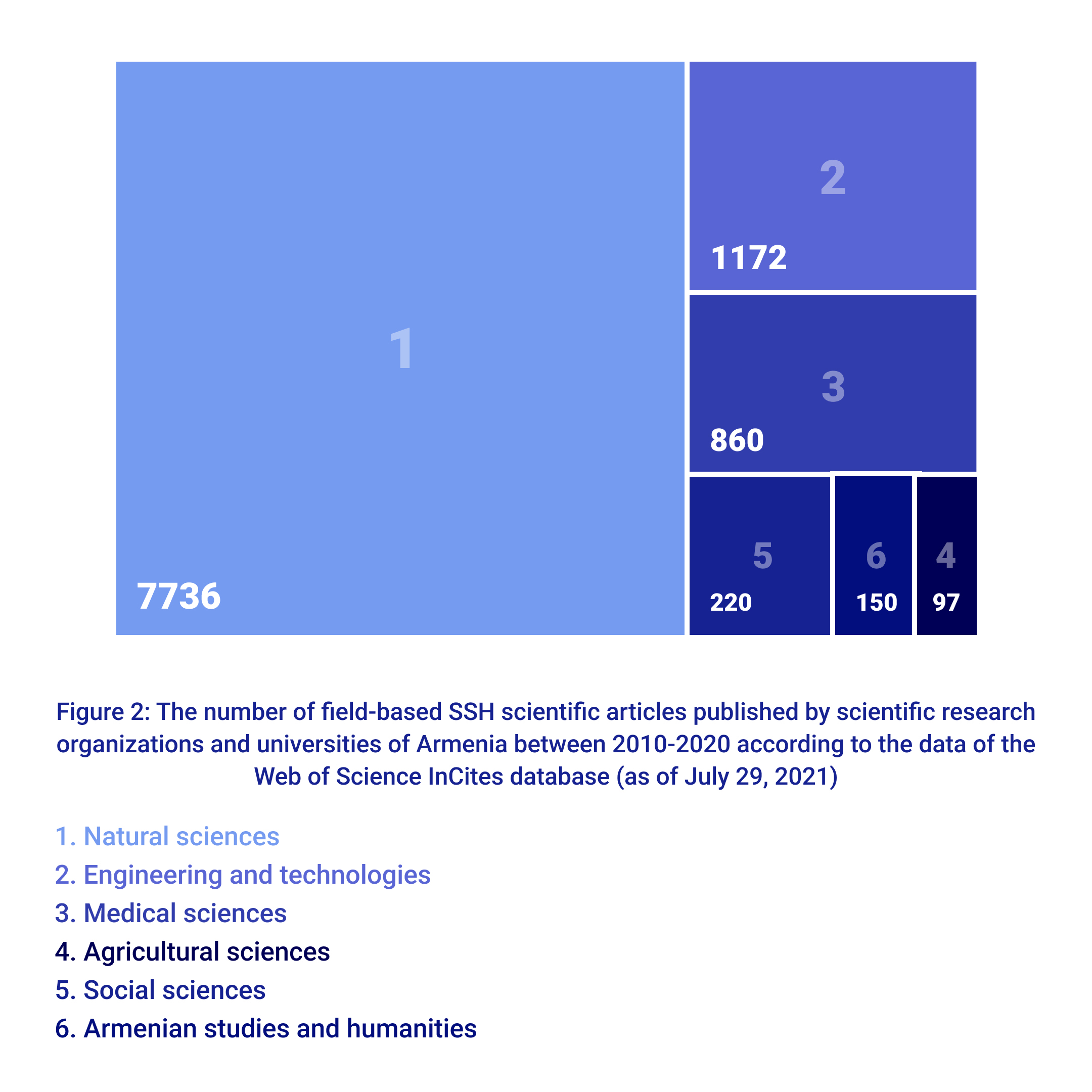

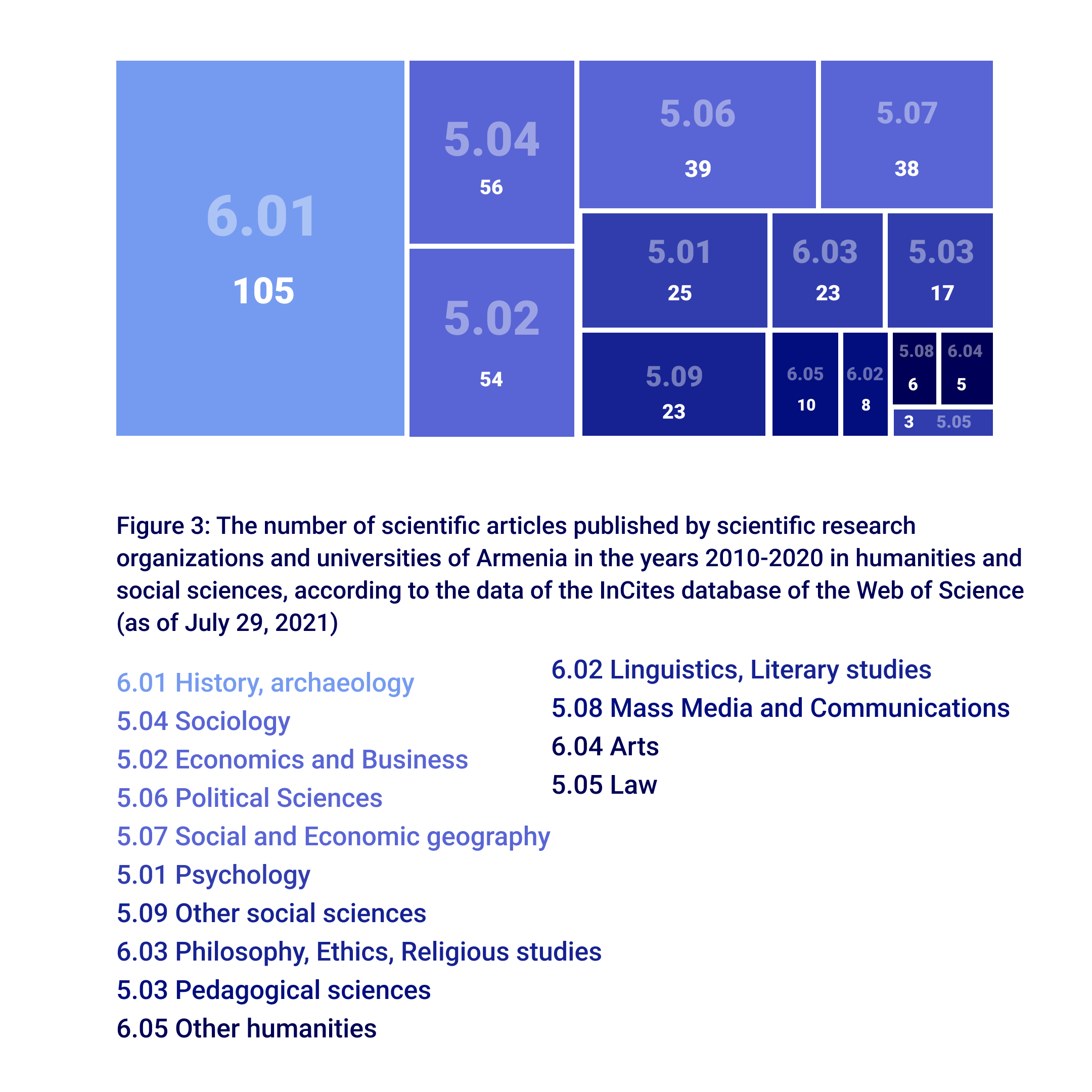

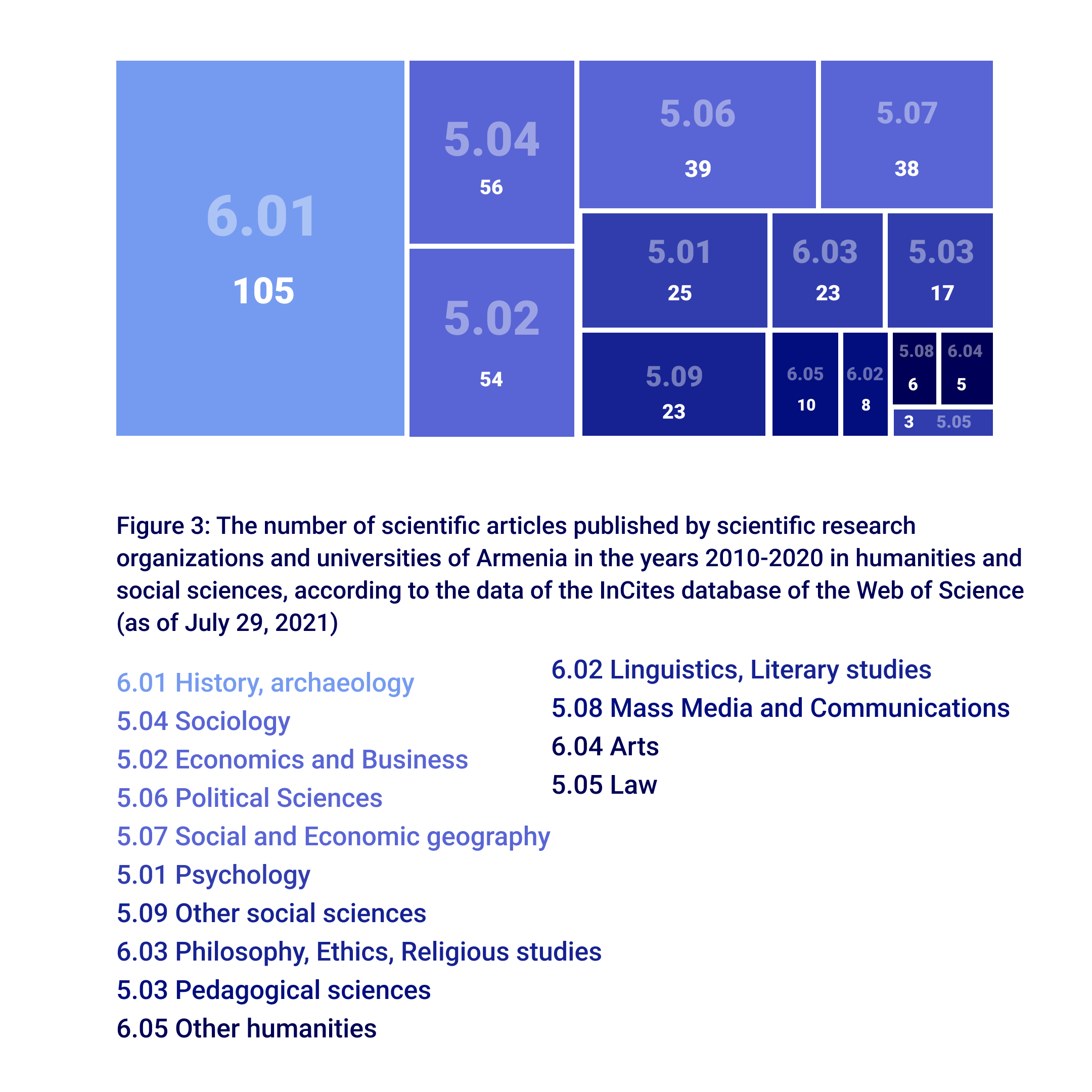

According to data provided by the Science Committee of Armenia, 246 articles in the social sciences and 166 articles in the humanities were published in academic journals between 2010 to 2022 by Armenian scientific research organizations and universities.

Historian, associate professor and Chair of World History at Yerevan State University, Smbat Hovhannisyan says that there has been a demand to develop cultural and national identity in Armenia and the period following the collapse of the Soviet Union has brought the matter to a crisis. “ Armenian identity is not shaped through a physicist. It is the language, literature, and history that build identity,” he argues.

Language, literature, and history are the cornerstones of national identity and are disciplines that have had little state support. “The Acharyan Language Institute [of the National Academy of Sciences] is in decline, with a few veteran specialists covering it and no prospect of succession,” emphasizes Gayane Shagoyan, cultural anthropologist and a leading researcher at the Institute of Archeology and Ethnography.

Are technological fixes without consideration of human conditions sufficient for tackling the challenges of a rapidly changing world? Shagoyan notes that whether it is a state-sponsored or private project, complex social and humanities applied research would be an invaluable tool in providing competent and well informed interventions with positive societal impact.

In spite of the neglected state of the humanities and social sciences, there are few individual researchers who are producing internationally respected work in the sciences. Smbat Hakobyan, social anthropologist and researcher at the Institute of Archeology and Ethnography believes that scientific research, thought and knowledge are not being created at the levels they should be in Armenia. Developing that sphere requires systemic changes. Where and how can such research be applied? These are the questions that decision-makers are not asking.

The graphics are provided by the Science Committee of the Republic of Armenia.

As a result of the continued marginalization of the humanities and social sciences, we lose out on crucial ways to understand and improve our environment and society – including things like achieving economic growth without losing social protections, sparking innovation, and enhancing national wellbeing.

Discussions within academia emphasize the value of the humanities and social sciences, including the lack of funding and the loss of jobs, but beyond those circles, the discussion centers on professors and institutions not teaching what is necessary in the way that it is necessary. Hovhannisyan thinks this is at least in part due to the legacy of the Soviet education system. Added to this is a new generation of students who know neither proficient English or Armenian. These are interconnected. “An incompetent lecture hall can’t be a source of motivation and continued excitement to the lecturer, and eventually pushes the lecturer back to their comfort zone,” Hovhannisyan argues.

As the Soviet Union collapsed in the early 1990s, society was exposed to new international work in the humanities and social sciences. Armenian academia was still translating work written 50-60 years earlier—between 1920-1940— when the West had moved on to discuss totally new issues. “Scientific thought has fallen behind. Academics in the humanities and social sciences are left out of the discussions,” says Smbat Hakobyan.

Shagoyan agrees that the humanities and social sciences in Armenia have not been updated for contemporary times. Moreover, they operate within a university system that resists modernization and reform.

Hovhannisyan notes that a few renowned Soviet Armenian researchers managed to break through the veil of Soviet ideology and get their work disseminated in the West. Western thought, however, did not find its way into Soviet Armenia because “many did not want to leave their comfort zone” as free thought was not welcome in the Soviet period, and because “others who did that became personae non gratae.”

This brings to light the problem of criticism being equated with treason in Armenian society. According to Ashot Voskanyan, PhD, the humanities, being largely ideological, don’t provide much space for a position that won’t be used in one way or another for political ends. “Therefore, it is a matter of national self-awareness, self-determination and identity,” Voskanyan says, adding that such undisguised politicization does not facilitate healthy discussions. “The underlying reason is not knowing ourselves as Armenian society.”

There is a need to better understand the societal impact of the humanities and social sciences and one must consider the available infrastructure to be able to set expectations against availability.

Armenian researchers face the dilemma of studying topics significant for Armenian society while needing to fulfill the quantity requirement of publications in foreign journals by their universities. Shagoyan says that standards and approaches common for the natural sciences by the Science Committee are also applied to the humanities and social sciences, an unacceptable practice itself. “The Science Committee prioritizes quantity rather than doing science on existing issues,” Shagoyan argues. The absence of journals in the Armenian language further degrades the development of Armenian research and the ability of Armenia to accommodate contemporary ideas and “the state is not taking thoughtful steps to solve the problem.”

Lethargic as it was, Soviet-era research was still characterized by the involvement of researchers who would be tasked to solve specific problems set forth by the government and would be remunerated. This has not been the case for decades in Armenia and the question is “how can researchers sustain themselves, especially with the dilapidated scientific base,” questions Voskanyan.

“To be a scientist in the humanities and social sciences in Armenia is to be unlucky,” jokes Hovhannisyan and adds that teaching at university is a sacrifice as there is little payment or recognition.

The crisis of faith in the value of the humanities and social sciences is directly reflected in the fact that students don’t consider majoring in history or literature for example, because they are concerned with what comes after university. When one says they are studying for a history degree, the response is almost always the same: “You want to be a teacher?” Sadly, today research institutions have to justify themselves by addressing labor market demands. A degree is a necessity for the job market and so it is preceded by the presumption that a degree has to be a springboard directly into a career. A teacher’s or a humanities researcher’s career may take decades for employment to be gainful if one is lucky.

The stability of the education system is crucial “no matter how many governments come and go,” says Shagoyan. This needs to be outlined as part of a longer term vision based on fundamental, in-depth research, to be followed regardless of political pendulum swings. “Such hemming and hawing have led to the fact that no government program has been completed and we keep wiping out one institution after another,” Shagoyan explains.

There is no doubt that humanities and social science research directly impacts society more than any other disciplines because of the social subsystems it encompasses – culture, nation, identity, state, etc. They however should not run the danger of falling behind technological solutions because their impact is not necessarily always evident or tangible.

Hovhannisyan says that the natural sciences will eventually come to an impasse if ignorance around the value of the humanities and social sciences continues. A major benefit of the humanities and social sciences is that they introduce different viewpoints and define ethical standards: they perhaps most importantly contribute to our understanding of ethics, the public good, because they emphasize the ability to question, think critically, communicate effectively and adapt to changing circumstances.

Studying and understanding the general picture of the sphere is essential to finding a solution, says Shagoyan, adding that sadly “there is no attempt.” One could study the research and educational systems of Baltic and Eastern European nations, those that are somewhat comparable to Armenia in terms of their achievements, their journey, their problems, and compare the models and figure out what their advantages are and how we can apply those advantages. “In this respect, the huge potential of the Diaspora is also totally ignored,” Shagoyan says.

The problems in the humanities and social sciences and their underlying reasons reveal a deep crisis and a lack of understanding about how to tackle the interconnected problems: lack of funds and resources, lack of researchers equipped with up-to-date knowledge, falling enrollment, deficient application of modern scientific solutions, poor quality of publications, absence of centers of excellence and of strong scientific groups or bright thinkers. The system is not properly institutionalized and does not contribute significantly to national knowledge production. Such knowledge is necessary to foster a sense of national identity as well as to facilitate modernization in the country.