Day after day, day after day,

We stuck, nor breath nor motion;

As idle as a painted ship

Upon a painted ocean.

– S.T. Coleridge[1]

Armenia’s current geopolitical situation hinges on an age-old question, linked with the orientation or reorientation of external and internal politics of the country. On the one hand, Armenia is still dependent on Russia. On the other, Armenia looks westwards, as Russia, its main ally, is unable or unwilling to fulfill its security obligations. The question has old roots; the actors might change but the problem remains the same. This problem in historiography is outlined in “Garosian’s Law,” which argues that Armenia –– being at the crossroads between East and West –– has thrived only when these two forces were at an equilibrium and neither was strong enough to exert disproportionate influence on its domestic affairs.[2]

Time and again, Armenia has been caught between these two worlds. In the face of this geopolitical conundrum, it is worth revisiting an oft neglected aspect of Armenian history in the debate about its political alignment, both presently and in the future: Armenia’s connection to Mediterranean civilizations.[3] This relationship is not emphasized because of Armenia’s current state, landlocked and disconnected from the Mediterranean sea, but it did have a significant impact on the progression of much of Armenian history. This article aims to explore the connection between Armenia and Armenians on one side, and the Mediterranean world on the other through three aspects: (i) the historical, which involves the various points of convergence and divergence between Armenia and the Mediterranean world; (ii) individuals and the movement of people: the Armenian mercantile network; and (iii) the poetic, represented mostly through the work of Osip Mandelstam. Each of these aspects showcase interactions between Armenia and the civilizations of the Mediterranean basin, emphasizing their similarities and differences.

Armenia and the Mediterranean

Is Armenia part of the Mediterranean world? A quick look at a map shows that landlocked Armenia is hardly part of the area around the “fearsome sea” (ահագին ծով).[4] The mountainous and arid terrain of Armenia is far from the azure, navigable world of Greek mythology. Xenophon, a mercenary in the service of Cyrus the Younger,[5] who left behind one of the earliest accounts of ancient Armenia said in Anabasis:

“There [in Armenia] they had as many good things as needed — sacrificial animals, grain, fragrant old wine, raisins, and all kinds of beans… For many unguents were found there, made of lard, and sesame, and from bitter almonds, and terebinth, which they used instead of olive oil. From these very same ingredients also a sweet oil was found.”[6]

The differences Xenophon highlighted between the dietary traditions of Armenians and the Greeks, a Mediterranean people, also neatly describe Armenians’ juxtaposition with the world of the Mediterranean basin. After all, Armenia, at the time Xenophon was crossing it, was still heavily influenced by the legacy of Urartu, a civilization that had roots in the ancient Near East. Some of these differences persist to this day. But since then, much has linked the Urartian culture of Armenia with the Greek world and its culture.

Xenophon’s account is not the only one about Armenia. Another, in certain respects an imaginary account, was penned by Strabo in the 1st century BCE, in which the Greek geographer not only narrates the history of Armenia but also attempts to deliver its origin story. Strabo’s story tells about one of the Argonauts, Armenus of Armenium, who gave his name to the country after finding shelter there with some of his men:

“There exists an ancient account of the origin of this nation to the following effect. Armenus of Armenium, a Thessalian city, which lies between Pherae and Larisa on the lake Boebe, accompanied Jason, as we have already said, in his expedition into Armenia, and from Armenus the country had its name, according to Cyrsilus the Pharsalian and Medius the Larisæan, persons who had accompanied the army of Alexander. Some of the followers of Armenus settled in Acilisene, which was formerly subject to the Sopheni; others in the Syspiritis, and spread as far as Calachene and Adiabene, beyond the borders of Armenia.”[7]

Strabo’s account proceeds to describe in detail the possible Thessalian origins of Armenian clothing and Armenians’ propensity for horse-riding. Rightfully discredited as a false account of the origins of Armenia, the story still proves that at least in one strand of Greek historical thought, Armenia was not at all foreign to the Greek world. What is even more interesting is that Strabo’s origin-myth can be attributed to an even earlier source –– to Medius of Larissa, a friend of Alexander the Great, who visited Armenia in 321 BCE. Medius tried to find ancestral connections between Armenians and Thessalians and in his attempt to do so, returned to the myth of the Argonauts.[8] Strabo was thus narrating a story which predated him by more than two centuries. Consistent with his origin-myth, Strabo “hellenizes” certain terms, as the word Ἰασόνεια (Jasonia), used to describe the sacrificial shrines.[9]

Another connection comes with the advent of Christianity in the Greco-Roman and Armenian world in the 4th century CE. Politically an attempt by Tiridates III to connect Armenia to the Roman Empire and steer it away from Sassanian influence, Armenia adopted Christianity as a state religion.[10] Although the political move fell short of its goal with the collapse of the Arsacid dynasty, the connection to Rome and later Constantinople did not vanish. The myth about Tiridates and Constantine the Great as protectors of the Christian faith shows that Armenians, in their millenarian and apocalyptic thinking, preserved the idea that they were connected to the wider Christian world based around the Mediterranean basin. This disposition did not disappear from Armenian millenarian thought until the later stages of the medieval period.[11]

Finally, in the Middle Ages, Armenians formally became a part of the Mediterranean oikoumene by founding the Kingdom of Cilicia, which developed along the Mediterranean shores and thrived on its sea trade. Cilicia, established on the rather vulnerable equilibrium of West and East, depended on the Crusades and assistance from the West to withstand relentless invasions from the East. The turbulent 14th century provides perhaps the finest example of the Armenian Kingdom’s dependency on the help of Western allies. In 1336, grain was sent from Apulia to Cilicia with money provided by Pope Benedict XII, to alleviate the famine that was spreading in the lands of Armenian King Leo IV. Eventually, Benedict XII’s reluctance to commit himself to the crusade led to the further deterioration of the Cilician Kingdom’s strength as it fought the Mamluks of Egypt. With the death of pro-Western Leo IV in 1341,[12] the French Lusignian Dynasty came to power in Cilicia creating yet another connection between Armenia and the Mediterranean.

Once the West no longer prioritized the salvation of the Holy Land, Cilicia quickly fell into decline and ultimately succumbed to the invading Mamluks. This was a sign of things to come as less than a century later, Constantinople itself fell to the Ottomans. Eventually the title of King of Armenia was claimed by a distant cousin of the last Cilican King Leo V –– John II of Cyprus –– and the title passed on to his descendants and onwards to the House of Savoy. The history of Cilicia lasted a relatively short 300 years, but the myth about the maritime kingdom has played a significant role in Armenians’ understanding of their identity. The kingdom’s lasting legacy also helped Armenians establish a mercantile network that spanned the length and breadth of the Mediterranean and stretched eastwards to the Indian Ocean.

Armenian Trade Networks In and Around the Mediterranean

Stateless and vanquished, the Armenians continued to actively participate in the world of the Mediterranean, albeit at that point solely through the activities of individual merchants and small merchant communities. In particular, the Armenian merchant community of New Julfa became a part of the Mediterranean mosaic of cultures and civilizations. As Karla Mallette observes, the Mediterranean is not only a geographical region demarcated by climate; it is also a region where the movement of people defines and defies geographical limits.[13] Armenian history especially, “helps us to see that geography itself — the landscape and the climate against which human history is enacted — is constituted in part by the unceasing movement of actors through it.”[14]

This merchant activity was accompanied and brought about by a period known as Pax Mongolica, one which allowed for safer land routes than was the case in the past centuries. Merchants could travel deeper inland into Eastern Europe and beyond, paving the way for the flow of goods from one side of the world to the other. The Mediterranean Sea was of central importance to the merchants’ activity, not only in the Levant, but also in the Black Sea basin. Venetians and the Genoese had vested interests in the trade and Armenians and Greeks were often forced to cooperate with investors from Italy to continue their activities unhindered.

Armenians, who were better connected in lands under Islamic rule, had a privilege that was denied to Catholics –– that of being able to trade with Muslims. In the long-term, this proved to be of value for Armenian merchants, as it mitigated inequalities they faced because of their faith vis-à-vis the Catholic Italians, who used the Monophysite faith of the Armenians as a pretext to deny them equal trading rights. To the Italians, Eastern Christians such as Greeks and Armenians were perceived as non-conformist.[15] These cultural boundaries however were overcome through the growing economic importance of the Armenian merchants.[16]

Armenians thus connected land and sea routes in their attempt to conduct trade between the East and the West, carrying not only material goods but also intangible values such as ideas. Trade was only one side of the coin, while the other was the transfer or establishment of Armenian cultural centers in the Mediterranean and beyond. In Italy, Armenian presence was felt the most.

Armenian printing presses in Livorno, Venice and elsewhere in the Mediterranean, proved to be a source of cultural rebirth of later centuries. The movement of merchants that guaranteed the transportation of knowledge and books, redefined certain intellectual approaches, primarily Eurocentric in nature, that were and still are predominant in the scholarship. The beginnings of Armenian printing go back to the early 16th century when Hakob Meghapart (Jacob the Sinner) first printed the Urbatagirk in 1512, which sparked the Armenians’ printing revolution. Without the mercantile connections, it would have been almost impossible to transport printed books from West to East, to Armenians inhabiting Constantinople and beyond. In the 18th century, the Mekhitarist Order still depended on this mercantile network to send books published in Venice to parts of Armenia under Ottoman rule.[17]

The development and ultimate success of the Armenian mercantile community was achieved through the dispersion of Armenians away from the Armenian highland and the Cilician Kingdom. Through this dispersion, Armenianness became a more mobile and wider phenomenon that transcended the geographical limits of Armenia, a landscape filled with “cruel” mountains, as once described by Fernand Braudel. Braudel then raises the question, heretofore unanswered, whether the success of individual Armenian merchants or mercantile communities led to the failure of Armenia as a political entity: “Armenia was lost through her own success.”[18] The statement is still somehow valid, as even today the successful individual achievements of Armenians in the diaspora or in the Third Republic do not reflect on the wider circles of Armenian society.

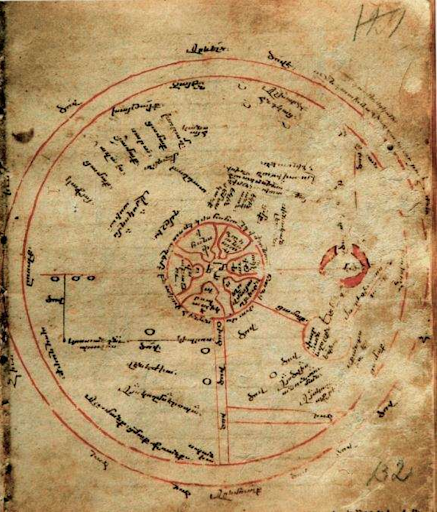

An Armenian mappa mundi (T-O type) with Jerusalem at its center.

The early 14th century map is a witness to the cultural exchange

prevalent in the Mediterranean world of the Middle Ages. (Rouben

Galichian: Countries South of the Caucasus in Medieval Maps:

Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan, Yerevan 2007, p. 152).

Also see

Magazine Issue N23

EVN Report’s October magazine issue N.E.W.S. [north, east, west, south] looks at the realignments taking place across the world and focuses on geopolitical tensions, shifts in world alliances and new rising powers creating an uncertain global terrain. Where does Armenia fit into these shifting alliances and rapidly changing power dynamics? What impact do hostile disinformation campaigns meant to manipulate domestic and foreign populations play? The articles featured in this issue attempt to answer some of these difficult questions.

Magazine Issue N4

Does history repeat itself? Recent events have served as a catalyst to discuss and ponder the lessons that might be drawn from history. More than ever, revisiting historical events through a new lens is essential for the Armenian people. Faced with similar circumstances from the past, we are collectively responsible for the chapter of Armenian history being written today.

Armenia and the Mediterranean, the Poetic Nexus

Another feature that connects Armenia and Mediterranean civilizations, can be rightfully termed as the mythic or the poetic connex. One can find traces of this in the work of Movses Khorenatsi. In his “History of Armenia”(Պատմություն հայոց), Khorenatsi briefly mentions Zarmayr, a semi-mythical figure who took part in the Trojan War on the side of the Trojans:

“The latter was sent to Priam by Teutamos with an army of Ethiopians and was killed by the braves of the Hellenes.” (Սա օգնական Պռիամու ի Տետամայ առաքեալ ընդ եթովպացի զօրուն՝ մեռանի ի քաջացն Հելլենացւոց։ )[19]

Khorenatsi’s account was not forgotten by Armenian historians of later ages. Mikayel Chamchyan refers to the story of Zarmayr in his history of Armenia.[20] Although in a brief and an episodic manner, Khorenatsi hints at the possibility of Armenians’ participation in the Trojan War, an event that features prominently both in historical experience of the Greeks and Romans. While one should not exaggerate the importance of Khorenatsi’s assertion, it still conveys a shared historical experience.

A further development of this view is seen in the works of Osip Mandelstam, a Russian poet with Polish-Jewish origins, who wrote “Journey to Armenia”, an unorthodox travelog about his stay in Armenia. The travelog connects Armenia, which was in Mandelstam’s eyes essentially Hellenistic, to the wider world of the Mediterranean. Mandelstam’s wife once summarized her husband’s vision of Mediterranean culture and how Armenia figured in this world:

“The tradition of culture for Mandelstam had never been interrupted: the European world and European thought were born in the Mediterranean –– there had begun that history in which he lived, and that poetry by which he subsisted. The cultures of the Caucasus –– the Black Sea –– were the same book: By which were taught the first men.”[21]

Mandelstam found everything in the Armenian way of life that did not yield to Soviet ways appealing –– elements that were archaic and remnants of a remote past. In his view, these were the same elements that connected Armenia with the classical world. In the words of the author: “The Armenians’ fullness of life, their rough tenderness, their noble inclination for hard work, their inexplicable aversion to any kind of metaphysics, and their splendid intimacy with the world of real things.”[22] Considering Mandelstam’s definition of Hellenism as a phenomenon in which people humanize objects surrounding them, one can understand how and why he saw Armenia as part of the classical world of the Mediterranean. In historical literature the statements of Mandelstam are of a piece with what Levon Zekiyan termed as the Armenian “pragma,” i.e. concreteness and the ability to adapt or readapt to the vicissitudes of their socio-political and cultural environment.[23]

Undoubtedly, there is also a personal element in Mandelstam’s approach to Armenia. In his eyes, Christianity represented the pinnacle of civilization and Armenia was the first to “reject the bearded cities of the East,” and become part of the Christendom that continued the legacy of the classical world.[24]

In another poem, Mandelstam talks of Masis as “rich with a Biblical carpet,” and refers to Christianity as the highest achievement of civilization, which found its abode in the mountains –– whether in Tuscany or in Armenia:

“Christianity seemed to belong essentially to the mountains of the Mediterranean world –– ‘the all-human’ hills ‘shining in Tuscany’ of a late poem. It was symbolized by the cold air of the mountains, and clothed in Apostolic poverty.”[25]

Mandelstam’s mythic narration can also be easily interrupted with a view that emphasizes the spatial unity of a world whose cultural unity has long been undone.[26] Armenia’s similarities to Italy and Greece, quintessential Mediterranean civilizations, are also apparent in the land’s ancient wine culture[27] –– a phenomenon that is corroborated by recent archaeological discoveries. However, in the Mediterranean, world history and myth often coincide and with all its historical complexity the Mediterranean is still covered by a veneer of myth. A reflection thereof is found in the magnum opus of Fernand Braudel, whose narrative often lapses into descriptions of cultural practices that seem to have been innate to the Mediterranean basin since times immemorial, or so Braudel posits.[28]

It is against this historic and mythic narrative backdrop that the mountains of Armenia with their Biblical texture merge with the Christian world of late antiquity around the Roman sea. To add to this romanticized version of Armenian history one needs to look no further than the origin story of Armenians in the writings of Strabo. This mythic origin story and Mandelstam’s poetic vision, although not entirely factual, augment each other and create a spatial continuity where Armenia becomes a part or an extension of the Mediterranean world.

Concluding Remarks

Mandelstam’s highly poetic vision of Armenia and civilization might not be completely applicable to historical reality, and while Armenia is not an extension of the Mediterranean world geographically, it does share fundamental cultural characteristics with most civilizations inhabiting the mare nostrum. Hence, one way in which Armenian history can be better understood, is to stop viewing its culture and civilization as a monolith, when it clearly comprises layers upon layers of diverse historical experiences spanning from Ancient Near Eastern Urartu to the Hellenic inclinations of Artaxiad Armenia, to the essentially Mediterranean Cilician Kingdom. From a scholarly perspective, such an integration of Armenia into the world of the Mediterranean might also help better understand a phenomenon termed as amoral familism. The term was first coined by Edward C. Banfield in his case study of an Italian village in Basilicata, where the nuclear family trumps all the other types of social and common interests.[29] It is worth asking whether there were similar factors at work in various parts of the Mediterranean that contributed to the emergence of the phenomenon, as described by Banfield. After all, comparative history might help elicit or identify common reasons for such a development in regions so diverse and yet so similar as southern Italy, Greece and the current Armenian Republic. This obviously does not suggest the complete reorientation of Armenian history into the orbit of Mediterranean studies –– an aim that is not only ambitious but also absurd, considering Armenians’ historical experience. Armenia has always been at a crossroads of cultures and civilizations, while preserving its own distinctive cultural characteristics.

As for more tangible and immediate political realities, perhaps it is advisable to think of the issue of civilizational belonging while devising a political strategy, which can shape the country’s trajectory for the foreseeable future. This is especially true at a time when an increasingly hostile Turkey troubles both Armenia and Greece. The two peoples, divided by geography but connected through historical experience, should find a way to cooperate to counter the bellicose intentions of their common historical adversary.

Footnotes:

[1] Taken from the poem The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.

[2] See: Sebouh Aslanian: From “Autonomous” to “Interactive” Histories: World History’s Challenge to Armenian Studies, in: An Armenian Mediterranean, Words and Worlds in Motion, 2018, p. 110.

[3] The choice of the plural form over the singular one is done with the intention of stressing the cultural diversity of the Mediterranean basin without downplaying the unity of the aforementioned geographical zone.

[4] This is how Armenian historians of the 5th century P’awstos Buzand and Agat‘angeghos referred to the sea in their Պատմություն Հայոց (History of the Armenians). See: Sergio La Porta: A Fish Out of Water? Armenia(ns) and the Mediterranean, in: An Armenian Mediterranean, Words and Worlds in Motion, 2018, p. 62. The term itself shows how Armenians collectively envisaged the sea as an overall dangerous place, foreign and undiscovered by them.

[5] Xenophon and his Ten Thousand were employed by Cyrus the Younger in an attempt to usurp the throne of the Achaemenid Persia from his elder brother Artaxerxes II. The failed attempt at usurpation eventually resulted in the march back to Greece (401 – 399 BCE) for Xenophon and his Greek soldiers during which they also passed through Armenia.

[6] Xenophon : Anabasis, Cambridge MA 1992, IV. 4. 9 – 13.

[7] Strabo: Geography, London 1903, XI. 14. 12.

[8] See: Giusto Traina: Strabo and the History of Armenia, in: The Routledge Companion to Strabo, London 2017, p. 94. Neither is this an isolated phenomenon in Greek thinking, as the ever-inquisitive Greek mind sought to find the possible Greek roots of other people and cultures as well. A specifically salient example of this is the debate amongst Greek intellectuals about the possible Greek origin of Rome, see: Arnaldo Momigliano: Die Ursprünge Roms, in: Wilfred Nippel (ed.): Ausgewählte Schriften, pp. 141-203.

[9] The original Iranian term reads yāzan. Ibid., p. 94.

[10] Contrary to the traditional date (301 CE) still accepted by the Armenian public and taught through the school textbooks, the current academic consensus with regards to the actual date when Tiridates III proclaimed Christianity as the state religion of the Armenian Kingdom falls on the year 313 CE, which corresponds to Constantine the Great’s Edict of Milan whereby Christians would no longer be persecuted for practicing their religion. For a more detailed discussion on the issue at hand see: Krzysztof Stopka: Armenia Christiana: Armenian Religious Identity and the Churches of Constantinople and Rome, Kraków 2017, pp. 29-32.

[11] The complex topic of Armenian apocalyptic thought cannot be addressed here, for a more detailed view on the issues that preoccupied the Armenian theologians of the late antiquity and middle ages see: S. Peter Cowe: The Reception of the Book of Daniel in Late Ancient and Medieval Armenian Society, in: The Armenian Apocalyptic Tradition, Boston Leiden, 2014, pp. 81-126. On the millenarian legend of Tiridates III and Constantine the Great see: Ibid, pp.106-107.

[12] For more on Benedict XII and his crusade policy with regards to the Cilician Kingdom see: Mike Carr: Benedict XII and the Crusades, in: Irene Bueno (ed.): Pope Benedict XII (1334-1342): The Guardian of Orthodoxy, Amsterdam 2018, pp. 224-228.

[13] Karla Mallette: The Mediterranean is Armenian, in: An Armenian Mediterranean, Words and Worlds in Motion, 2018, p. 315.

[14] Ibid., p. 314.

[15] Alexandr Osipian: Practices of Integration and Segregation: Armenian Trading Diasporas in Their Interaction with the Genoese and Venetian Colonies in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea (1289-1484), in: Union in Separation: diasporic Groups and Identities in the Eastern Mediterranean (1100-1800), Rome 2015, p. 357.

[16] Ibid., p. 359.

[17] See: Sebouh Aslanian: Port Cities and Printers Reflections on Early Modern Global Armenian Print Culture, in: Book History 17 (2014), pp. 51-93, p. 63.

[18] Fernand Braudel: The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II, Vol. I, Los Angeles London 1995, p. 51.

[19] Khorenatsi: History of Armenians, Book 1, Chapter 19.

[20] Mikayel Chamchian: History of Armenia from the Beginning of the World until the Year of Our Lord 1784, Vol. I, Chapter 8.

[21] See: Henry Gifford: Mandelstam and the Journey, in: Osip Mandelstam: Journey to Armenia, Memmingen 2011, p. 14.

[22] Ibid., p. 60.

[23] Boghos Levon Zekiyan: Christianity to modernity, in: Edmund Herzig & Marina Kurkchiyan: The Armenians Past and present in the making of national identity, New York 2005, p. 56.

[24] Mandelstam: Journey, p. 8.

[25] Ibid., p. 16.

[26] An issue that lies at the core of Peter Brown’s classical work The World of Late Antiquity. See: Ibid., London 1971, pp. 7-9.

[27] Monas, Sidney: Introduction: Friends & Enemies of the Word, in: Osip Mandelstam: Selected Essays, Austin 1977, p. 42.

[28] Statements like this one are a case in point: “Victor Bérard [French historian and classical philologist] discovered the landscapes of the Odyssey in the Mediterranean under his own eyes. But often, as well as Corfu, the island of the Phaeacians, or Djerba, the island of the Lotus-Eaters, one can find Ulysses himself, man unchanged after the passing of many centuries.” Braudel: Mediterranean, p. 353.

[29] Edward C. Banfield: The Moral Basis of a Backward Society, New York 1958.

*The title of the article is a play of words on the magnum opus of Fernand Braudel: The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II.

Great post with mind-boggling insights!