Armenia’s Government has taken acute measures to combat COVID-19, the novel coronavirus disease, by implementing a set of aggressive policies aimed at containing the epidemic. The perceived relative success of these measures–although it is quite premature to speak of any kind of success at this stage–also recognizes the inevitable: the virus cannot be fully contained and it is a matter of time before its transmission escalates. This is precisely what has been observed in much of Europe, Asia, and North America: containment strategies remain limited, so governments are proceeding with more complex mitigation strategies.

The Armenian Government’s recent declaration of a state of emergency signals a clear recognition of the limits of containment policies. Controlling the spread of highly-contagious viruses is commensurate to controlling human nature: it is extremely difficult to do. More severe methods to contain the spread, however, can be imposed. Yet these are likely to be fraught with diminishing yield as well as relying on draconian measures, which are more compatible with non-democratic regimes. Such measures may not be tenable for open, democratic societies. The transition to a mitigation strategy, generally speaking, becomes the next step in anticipation of a wider outbreak. Mitigation strategies include a wide-range of policies: limited social mobility, restrictions on travel, social distancing, and preparing the health care system for a potential outbreak. Epidemic management, then, is not specific to healthcare – it is administrative, infrastructural, systemic, and political.

This, inevitably, brings about a range of genuine questions about Armenia’s preparedness and its overall strategic approach. Does Armenia have the sufficient number of health care providers and technical experts to develop and implement its epidemic strategy? How durable and sustainable is Armenia’s healthcare infrastructure, and will it be able to absorb a wide outbreak; namely, what is Armenia’s “surge capacity?” What do Armenia’s stockpiles look like, and does it have sufficient availability of medicine and medical equipment to treat an excessive number of patients? Is Armenia correctly and efficiently utilizing its resources, and how instrumental can the Diaspora be in providing not only material resources, but also expert knowledge and highly-trained professionals? Why have Armenia’s epidemic policies been reactive and ad-hoc, and how can it utilize Diasporan medical and epidemic management experts to develop long-term proactive strategies?

Considering the coronavirus epidemic is both a crisis and national emergency, this has also become a concern for the broader Armenian nation. To mollify some of these concerns, this article will address several important frameworks: 1) Armenia’s current strategy for managing the coronavirus and mechanisms through which this can be enhanced; 2) An analysis of the country’s administrative and infrastructural capabilities; and 3) How experts from the Diaspora, in collaboration with the Armenian Government, can enhance and advance Armenia’s ability to both combat the coronavirus outbreak as well as future epidemics?

Current State of Affairs

The overarching current strategy of the Armenian government in managing the coronavirus has been intense and aggressive containment. The strategic initiative has relied on controlling the spread, swiftly testing suspected individuals, implementing quarantine mechanisms, and expanding on community containment. The modus operandi of the government strategy appears to be targeted and efficient: identify, test, diagnose and control.

Generally speaking, the current epidemic management strategy has been relatively adequate. There are, however, minor concerns, most important of which revolve around institutional and bureaucratic coordination and efficiency. While the Ministry of Health has taken the lead on this crisis, it is important to consider why the Ministry of Emergency Situations has had such a limited role? Further, why doesn’t Armenia have an institutionalized and established task force or state commission on such matters, and why did it have to result to ad-hoc measures, such as hastily forming one under the Deputy Prime Minister? Are there possible concerns of bureaucratic overlapping? For example, the Ministry of Emergency Situations formed a task force on March 18 to assist in inter-agency/ministry coordination: Why is this being formed almost three weeks after the fact and how functionally relevant is it considering the primary task force formed under the Deputy Prime Minister?

These concerns, on the other hand, have been eased by an overall expeditious and organized response by the Government. While having to close borders with Iran, the government eased the economic fallout by keeping commerce active through an innovative method of having the police escort Iranian trucks and its drivers. When food scarcity became a concern in the marz/regional municipalities after the declaration of a state of emergency, the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs stepped in to ease such concerns by offering food distribution to socially vulnerable families. When schools and universities became suspended, the Ministry of Education launched heravor.armedu.am, an online learning platform to placate educational concerns. Understanding when traditional distrust of government can cripple communication, the current Government has reinforced transparency with periodic updates by the Ministry of Health, continuous communication by the Prime Minister, and the launching of the Armenian Unified Infocenter. And perhaps most importantly, to marginalize the economic fallout, the Government has unveiled a $300 million economic aid package.

Analytical considerations, of course, cannot be indifferent to either of the developments: both shortcomings and accomplishments must be equally and objectively gauged. However, all things being equal, one must also be cognizant of the context. Armenia is a developing country with limited resources; further augmenting the context is the limited scope of experience that its Government has in dealing with this specific type of situation. As such, it would be quite unreasonable to compare the efficacy of governments who have dealt with numerous pandemics/epidemics with that of Armenia. That being said, the severe problems faced by developed countries is clearly indicative of what the entire world is facing. The European response has been subpar, federal mismanagement in the U.S. is compounding the crises, and much of Eurasia and the Middle East are beginning to reckon with the fallout. With the general exceptions of Singapore, South Korea, and Japan, epidemic management by the developed world had been unremarkable. This clearly merits a discussion of managing expectations.

Enhancing Current Strategy

There’s a reason why every government in the world is struggling with the coronavirus. The novelty of this particular virus, along with significant unknowns about its natural history, has hampered treatment and management.[1] There are three main mechanisms the Armenian government may adapt that can enhance the country’s epidemic management strategy. One mechanism would be bringing in Diaspora (international) experts. Complementing local expertise with specialists from the Diaspora would allow us to “punch above our weight” by pooling the collective resources and experiences that the outside perspective would bring. This would undoubtedly lead to the development of more robust policies, strategies and interventions to curtail and manage the current situation. Examples of expertise which exists within the Diaspora and that are relevant to this pandemic are specialists in public health, disaster management and emergency preparedness, epidemiologists, psychologists, and numerous clinical specialists (e.g. infectious diseases, critical care/pulmonology, surgery, pediatrics, pathology, geriatrics, etc). The reach can also extend beyond traditional health care fields to include policymakers, economists, supply chain managers, communication strategists, and educators.

The second mechanism would be to improve Armenia’s disease epidemiology and response methods and strategies. Armenia must develop a continuous process of evaluating and improving disease surveillance and control methods that incorporate lessons from past experiences to optimize the current and future responses to similar situations. Consider the H1N1 virus in 2016, where Armenia had approximately 900 cases that resulted in 19 deaths*. Were there lessons learned from this experience? Were there further refinements to the nation’s surge capacity that are applicable to the current situation? There has not been reference to any protocols, guidelines, or experiences from 2016 or other similar situations.[2]

These limitations must be overcome by developing institutions strong enough to withstand time, resource constraints, and political changes. Similarly, it remains to be determined whether the response to this recent coronavirus experience is being concurrently assessed and chronicled for reference in the future. This is a critical component of the so-called “recovery phase” from an emergency situation, for which Armenia needs to develop robust strategies. As part of the “recovery phase,” overall response to a disaster or epidemic is thoroughly assessed, strengths and weaknesses are identified, and plans/policies for the next emergency situations are modified and improved. Research demonstrates that implementing this approach, concurrently and immediately following an event, is far more effective than undertaking the process after the fact.[3] Collectively enhancing Armenia’s disease surveillance will inherently enhance the government’s epidemic management strategy.

The third mechanism would be the organization and implementation of routine drills and practice at all levels of healthcare delivery. In contrast to other sectors (e.g. frequent military/defense drills), exercises and simulations to prepare for extraordinary situations are not commonplace throughout Armenia’s health care system, whether at the ministry/government level, or at the hospital or community level. In all developed health care systems, institutions such as departments of public health, hospitals, emergency medical systems, etc. routinely practice their responses to emergency situations and have well-defined bodies that coordinate such drills. This is lacking in Armenia. If we consider the physiologic/health effects on individuals (putting prevention/containment aside for a moment), there is nothing novel about the manifestations of coronavirus on the human body. The virus causes conditions that are seen in health care everywhere and everyday. Presumably, Armenia has most of the capacity necessary to treat individual patients with coronavirus. The difficult part of this situation is preparing for and dealing with the potential for these individual cases to happen at a frequency that overloads the capacity of the system.

There is an entire field of public health dedicated to emergency preparedness and disaster management, with a science to developing governance (an emergency operation center, incident commander, etc), and plans for surge capacity (the ability to evaluate and care for a markedly increased volume of patients—one that challenges or exceeds normal operating capacity.)[4] The ad-hoc nature of Armenia’s coronavirus task force is indicative of the deficiency in long-term strategic planning. What is Armenia’s surge capacity should the coronavirus outbreak exceed current expectations? What is the governance capacity for emergency preparedness and disaster management? The country’s stockpiles, such as ventilators and hospital beds, may be enough for the current state of affairs: but are contingency plans developed for the long term? And how well-developed is its “recovery phase”? Addressing these crucial factors will exponentially enhance Armenia’s policies and long-term strategies for epidemic and disaster management.

Armenia’s Administrative and Infrastructural Capabilities

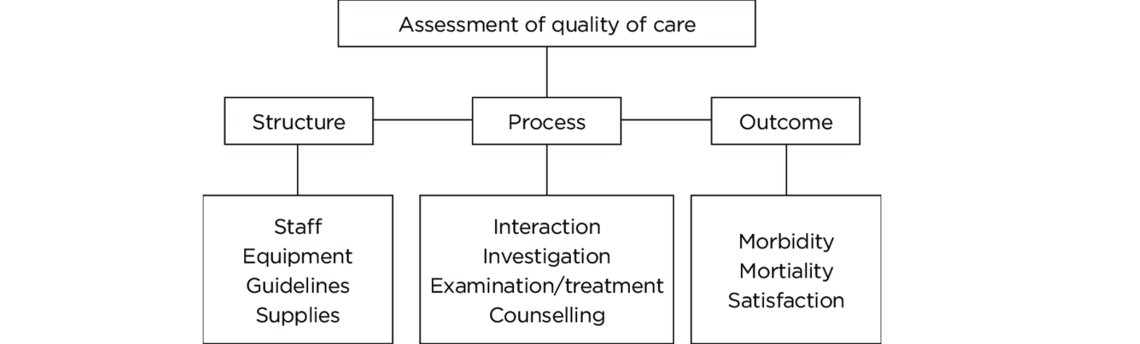

Analysis of Armenia’s administrative and infrastructural capabilities within health care will be conducted through the Donabedian Quality Framework, a classification model that assesses the quality of health care systems based on measures of structure, process and outcome.[5]

Since the coronavirus pandemic is still playing out, evaluation of outcome will not be applicable to this analysis: it is far too early to assess outcomes.

Structure

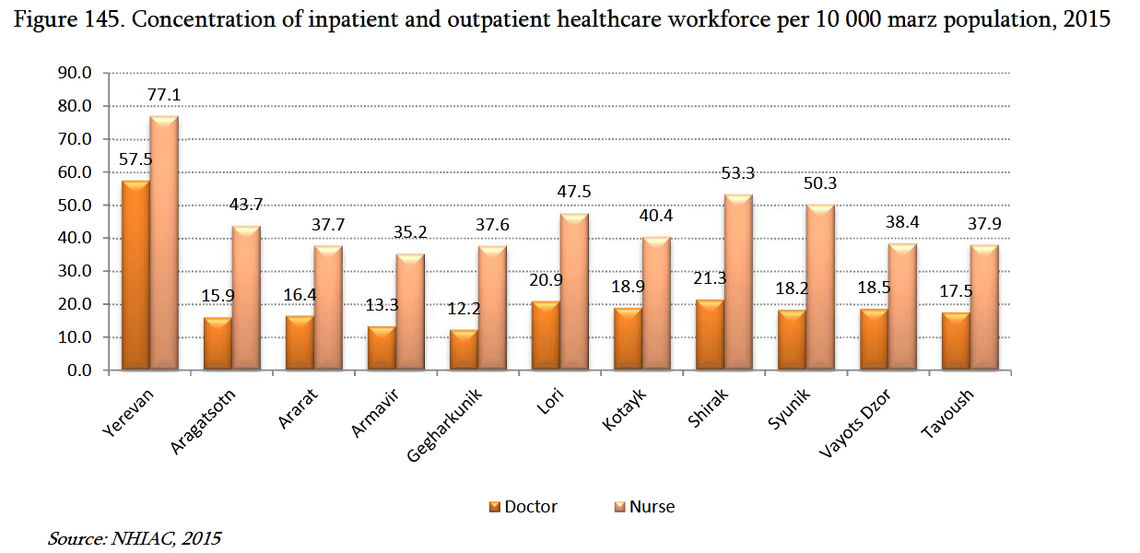

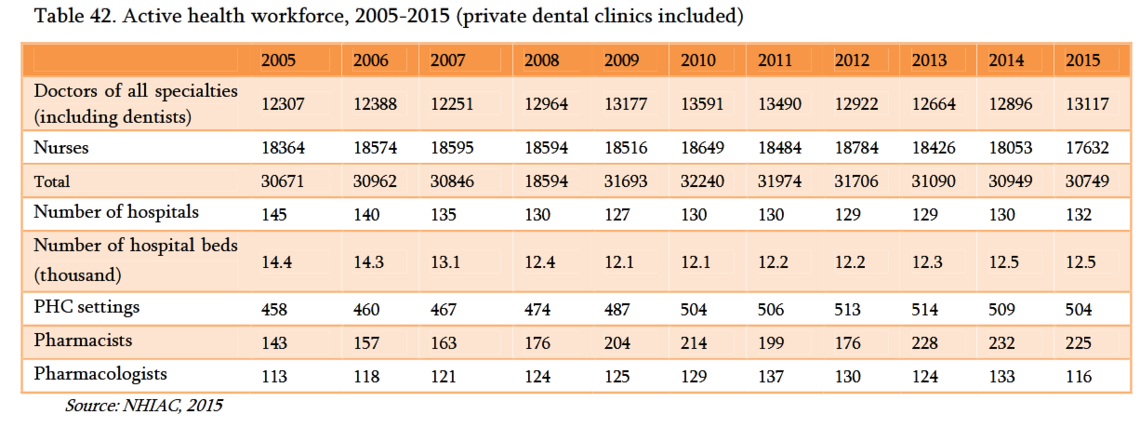

In relative terms, Armenia’s health care system is severely underfunded by the state, with less than 1.6% of GDP going to health care expenditure (one of lowest in the world) and more than 50% of all health care expenditure coming from out-of-pocket spending (one of the highest in the world).[6] Thus, from a structural lens, the health care system is chronically underfunded, which creates systemic limitations that lead to significant issues with access, governance, and quality of care. That being said, the health care workforce remains robust, as the healthcare system does not suffer from major deficiency in physicians. There is, however, a serious disparity between rural areas and the capital: Yerevan has an over-concentration of physicians in relation to the rest of the country.

Furthermore, there is a disproportionate share of specialists compared to primary care physicians. This disproportion, however, may be advantageous with the current situation: the vigorous surge capacity of specialists to deal with particular complications of the coronavirus. Overall, the numerical distribution is revealing: average number of physicians per 10,000 capita in Armenia is 43.7, while comparatively, the per capita average for Europe is approximately 30.6. This numerical advantage is relatively positive. However, circumstances regarding registered nurses is the opposite: 88.3 per 10,000 in Europe versus 45.6 per 10,000 in Armenia. This numerical deficiency is relatively negative.

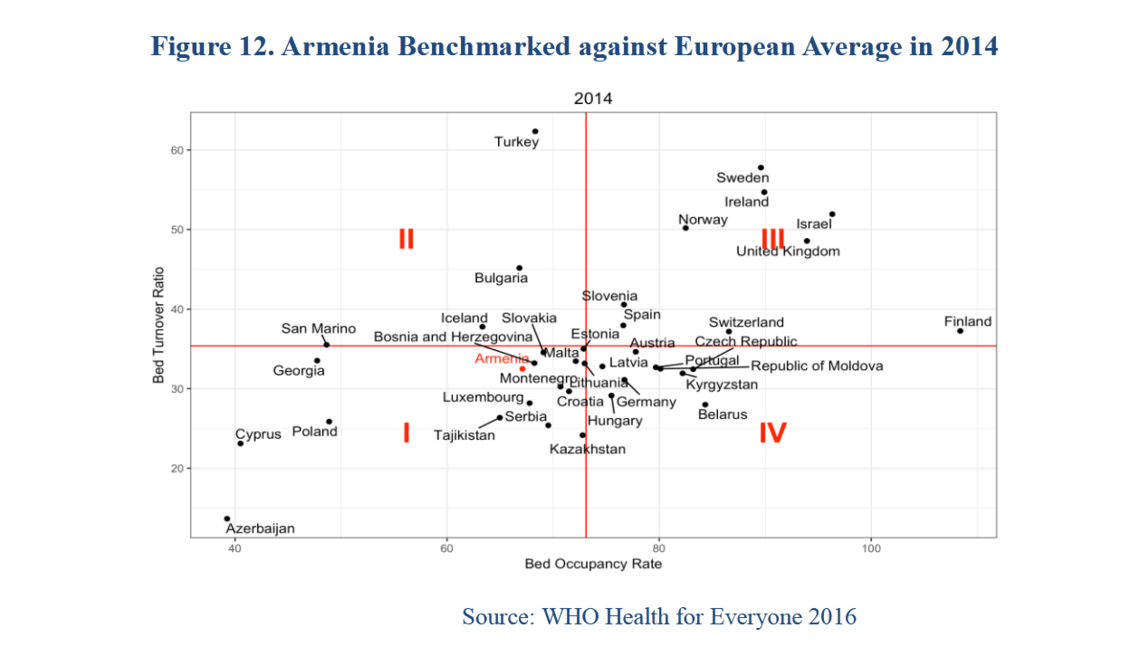

Another important structural variable during pandemics is hospital capacity. Assuming a population of 3 million, Armenia’s hospital bed capacity is 4.2 beds per 10,000 individuals. This is relatively higher than Canada at 2.5 beds, United States at 2.8 beds, and Italy at 3.2 beds. However, compared to a country that demonstrated excellent surge capacity during this pandemic, South Korea, which has 12.8 beds, the comparative structural assessment becomes a bit clearer. Here again, the relative excess of per capita beds as well as low bed occupancy rates, which during most times contribute to inefficiency and waste within the system, may actually serve to increase Armenia’s surge capacity in times of need. There are, however, more nuanced factors that will need to be taken into consideration: proportion of beds that are intensive care unit (ICU) beds; number of beds with infection control/negative pressure rooms; and availability of such beds in all hospitals (infectious illnesses, for example, typically get treated in a centralized place, i.e. Nork infection hospital, which is currently being expanded to deal with the pandemic). Thus, while overall surge capacity theoretically exists in terms of number of beds, there are still very important factors that need to be taken into consideration to address limitations.

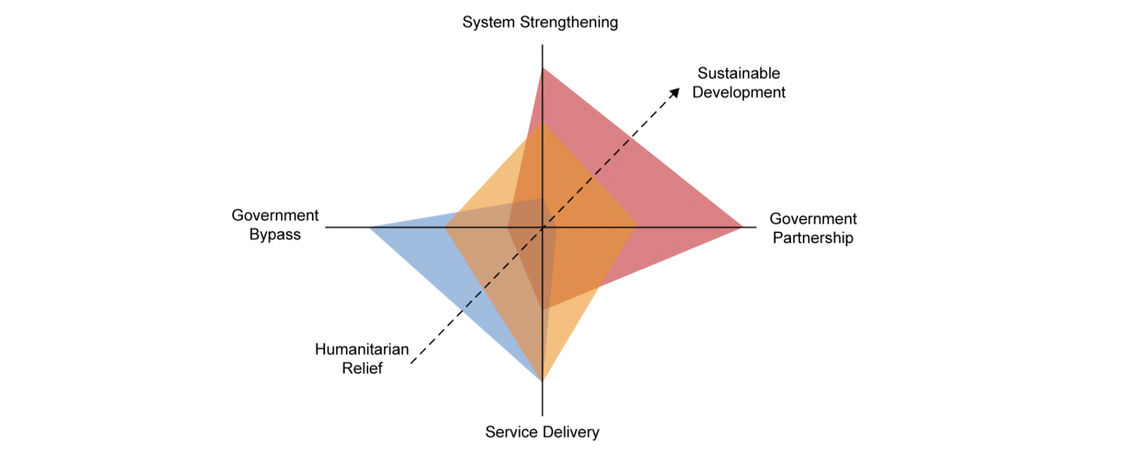

Ever since Armenia’s independence, the approach of the Diaspora, and understandably so, has followed the process of providing “Humanitarian Relief” within the realm of “Government Bypass.” The corruption and authoritarianism of the previous regimes were simply not conducive to “Government Partnership.” The Velvet Revolution exponentially altered this dynamic. With enhanced trust in the government, the objective now is for the Diaspora to chaperone the maturation of the dotted arrow from “Humanitarian Relief” to “Sustainable Development,” which is only tenable by “System Strengthening” and “Government Partnership.” Thus, to alleviate ad-hoc, non-systemic approaches to crisis, Diaspora’s participation must become institutionalized: a sustainable partnership with the government.

A developed model that conceptualizes this proposition is the concept of Diaspora Advisory Councils (DAC), with the formation of the council being defined by topical experts.[9] Diaspora Advisory Councils are conceptualized as quasi-governmental bodies that function transnationally, where Diaspora experts serve on government-recognized Councils that advise and assist the Armenian state. DACs liaise and coordinate their formalized activities through the Office of Diaspora Affairs. In the realm of healthcare and the specific emphasis on the recent crisis, the modality of the advisory council addressed will be that of a Diaspora Advisory Council on Healthcare.

The role of a Diaspora Advisory Council on Healthcare (DACH) can be crucial in “graduating up the arrow,” thus allowing for sustainable healthcare development, strengthening of the healthcare system, and doing this with a well-developed government partnership. As a specific case study, let’s consider the recent coronavirus crisis.

The vertical axis in our diagram begins with “Service Delivery.” At this level, the Diaspora, for example, can send gloves, masks, and other such requested necessities. But this is not a long-term modular approach. To move up the axis toward “System Strengthening,” the Diaspora, under the tutelage of a DACH, can do the following: enhance Armenia’s supply chain management, contribute to development of policies that improve disaster management, co-develop locally relevant infectious disease protocols, participate in the implementation and assessment of these protocols, and lobby/educate the government for increased health care funding.

For the horizontal axis, the necessity of a state-centric approach is obvious and straightforward. The formation of DACs becomes crucial, as this will allow the Office of Diaspora Affairs to coordinate bi-directional interactions between Armenia and its Diaspora. DACs will field requests directly from the Government, and subsequently identify and channel the requests to appropriate sectors in the Diaspora. Further, DACs can contribute by refining said requests and coordinating other requests from various government bodies.

On the reverse side, DACs can field, filter and deliver offers for assistance from the Diaspora to the pertinent state bodies. DACs, having formal recognition from the Armenian state, can encourage and coordinate collaboration between the various Diaspora structures to improve efficiency. They can also provide periodic briefings on state of affairs to the Diaspora constituency, and when necessary, as expert bodies, do the same with the governments of host states. And perhaps just as importantly, having formal government recognition, DAC representatives will also sit on state commissions that are formed when crises or emergencies develop in Armenia.

While the coronavirus pandemic, at this stage, is in the emergent end of the spectrum, even in this situation there is an opportunity to enhance the concepts of system strengthening, government partnership and intra/inter Diaspora as well as Diaspora-Armenia collaboration. The role of DACs, then, is the missing link that will serve as the transnational coordinating body. Certainly, if we apply the proposed conceptual model–with the incorporation of DACs–to a non-emergent situation (such as, for example, improving oncology care in Armenia), the ability of the Diaspora to better the Homeland becomes even more potent. And just as importantly, it also gives the Diaspora agency: the Diaspora becomes an even more significant stakeholder.

In conclusion, crisis management is not only specific to the Armenian state: it is a phenomenon that concerns the entire Armenian nation. The capacity and capabilities of the Armenian state must be enhanced and supported by the experts and professionals of its Diaspora in an official, coordinated format. The experience of combating this recent pandemic can and should serve as an important foundation for developing long-term and institutionalized mechanisms of crisis management.

*Correction: An earlier version stated that “Armenia had approximately 170 cases that resulted in 18 deaths,” the numbers have since been correctd.

——————–