Driving through a thick fog on a mid-October night, I cross the border and enter Artsakh. As darkness falls, I can’t see the “Free Artsakh Welcomes You” sign. Yet, I can tell I am already there since Russian military posts can’t be missed like the sign in the fog. The white-blue-red illumination is visible from a distance. We hear barev dzez (hello in Armenian) with a strong Russian accent, a kind request to show our passports, followed by bari chanaparh (have a nice trip). Battling the long way to Stepanakert, at the next Russian checkpoint, I hear Dobryi vecher. Dokumenty, pozhaluista. (Good evening. Your documents, please). Their language alternates between Russian and broken Armenian at every checkpoint until the last Russian soldier, who asks us to take him to another post nearby. “I don’t know what your prime minister will decide, but the Russians are here for a long time,” he says in response to one of my questions. He gets off after a short while, and we reach Stepanakert.

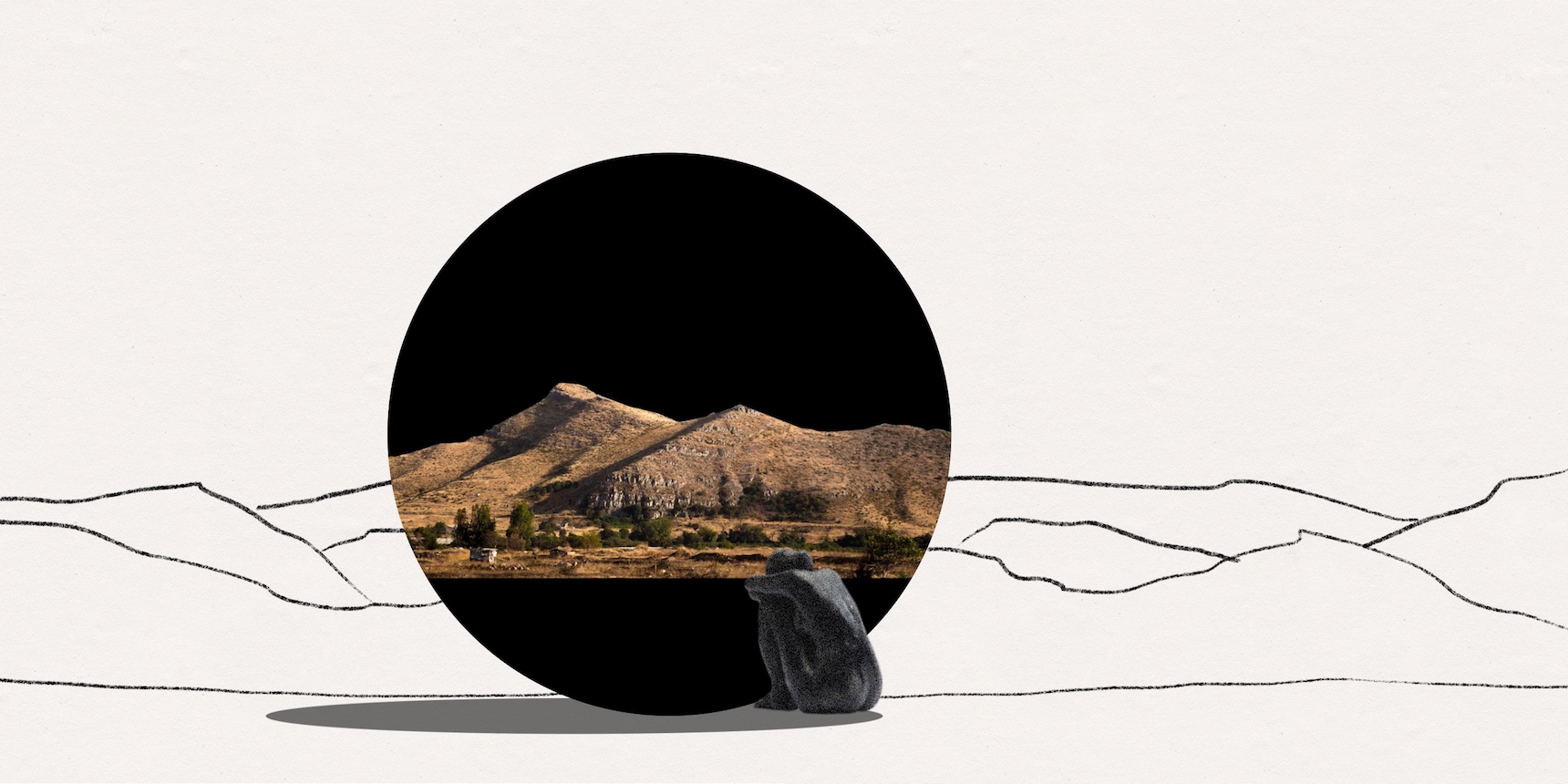

For a moment, I envision the “We Are Our Mountains” monument, which we call Tatik-Papik, welcoming me. Today, however, the monument for the fallen soldiers of the First Karabakh War greets me as I come from the opposite direction, through a new road.

I start my morning at Bazhak, a popular downtown cafe and my favorite spot to savor a Spanish cheesecake or drink French wine. I hear Toto Cutugno’s Lasciatemi Cantare playing, followed by Edith Piaf’s La Foule, the European ambiance distracting me from the Russian flags and soldiers from the previous evening. Enjoying my favorite dessert, I recall Hayk’s story. He was injured in the war, lost his cafe in Shushi, but somehow found the willpower to open Bazhak in Stepanakert.

After finishing my cheesecake and coffee, I go on a stroll. The benches in Shahumyan Park are always occupied by a group of older people who leave only at nightfall. Passing by them, I hear political conversations – perhaps the only topic that the people of Artsakh discuss with such consistency. I approach one person to talk, but eight men join our discussion. I realize why these men are always so cohesive – their political views match entirely. “We should organize a referendum at Renaissance Square and join Russia,” one says. “You’re too young; you just don’t understand that our only real ally is Russia. Russia is the strongest country in the world,” adds someone else. “Marcon (mispronouncing “Macron”) is a super guy; Marcon is a real man,” another says, contradicting their initial glorification of Russia, whom their idol Macron accused of destabilizing the region. If I stay any longer, the men might convince me that Russia is our only savior and that I should beg Putin to recognize Artsakh as part of Russia. So I quietly vanish from this elderly party nostalgic for the Soviet years.

It is not surprising that people in a small self-recognized state, threatened by a genocidal neighbor, “protected” by Russian peacekeepers, rely on Russia. On a few buses in Stepanakert, one can see the Z sign, the symbol of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. A newly opened shop in Stepanakert is called Voentorg, the name of a sales network that serves the Russian army. In the window is a mannequin in a Russian military uniform, with the Russian peacekeeping forces insignia on the hand and on the helmet. Inside the shop, the Russian peacekeeping flag hangs at equal height with the Artsakh flag. The contradictions and complexity of Artsakh’s situation are more explicit in a neighboring hotel, where a shelf features Russian military products for sale, even as all the writing inside is in English and Armenian, with the flags of Armenia and Artsakh fluttering on its terrace.

The red-blue-orange tricolor is still more common in the city, from Renaissance Square to the central market, where huge flags of Artsakh hang above boxes of fruits and vegetables. The salespeople there mainly come from villages to sell their harvest in the city. Some are grouped together like the men at Pyatachok, and I am sure that they are sharing thoughts on the country’s situation, or something connected with the hardships of life. I approach them. “What can we even say? It’s just chaos,” one says. “Only a miracle can save us,” says another. One of the sellers gives me dried fruits and begins talking. “You think I have a place to go? I don’t have a place in Armenia. Maybe I would think of leaving Artsakh after all this if I had some money, but I have neither money nor a place to move. I want to live here, my home is here, but everything is so uncertain. We may wake up tomorrow and find Azeris surrounding us,” he says in despair. “Anyway, good luck to you.”

Walking home, I pass through Renaissance Square, where the Karabakh Movement began in 1988. Back then, Armenians fired up grills in the square to distribute hot meals during round-the-clock demonstrations as people stood in the freezing weather to voice their demands. I dreamed of seeing this kind of unity again, but I saw only two small tents pitched in the center of the square, with flags of Armenia and Artsakh on each. I knew who was inside – a group of people who organize most protests in post-war Artsakh. The tents have been there for almost 50 days, they tell me. Starting from September, when Armenia’s Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan announced “painful decisions,” the square hosted thousands of people with posters addressed to the international community, reading “We are not Azerbaijani citizens” or “Is gas more important than our lives?” The posters were then placed along the square, so that passersby could see them. Still, I hope the square will soon resemble the images from 1988.

I live on a narrow street in the city center, where nine private houses are located, most of them decades old. In the last few months, two of my neighbors began renovations. One family is expanding their home by building a second floor, and the other is constructing a new building in their garden. This emphasizes one essential fact about the people of Artsakh: they seek a better life in Artsakh. They are determined to stay and ameliorate their living conditions despite all the threats and risks. I see another neighbor, Ashot, standing in front of my house, observing the construction on the opposite side. I hadn’t seen it before, so I talked to Ashot. “I am establishing a small food court here; we will make and sell shawarma and barbecue,” he said. People seem to be living in the normal rhythm of life. After seeing cafe terraces full of young people, hearing the boisterous voices of children from kindergartens, and piano melodies from the musical college, I couldn’t think otherwise. I recall how my cousin’s class has 40 children. Forty children! When I was his age, schools accepted a maximum of 30 students per class. Then I thought of the laundry hanging traditionally in Stepanakert, the clotheslines stretching from one building to another, clothing pinned to the line from smaller to bigger articles. It was the first detail to give me joy in November 2020, when I had just returned to Stepanakert after the “ceasefire.” As long as the lines of laundry are strung up, everything will be alright, I thought.

Around a month ago, I came to Stepanakert for my friend’s wedding. Some of my classmates also got married this year. Overall, statistics show an increase in birth and marriage rates in Artsakh, as typically happens after wars. I often heard Armenian party music while passing by wedding halls or saw small crowds near churches, with brides dressed in white.

This time, the wedding season is almost over and there is no traditional music to be heard during my late evening walk. Instead, the brightly illuminated fountains in Renaissance Square are visible in the hazy October dullness, and I can just barely hear the melodies of soft Armenian music. The benches become vacant as soon as darkness falls, and the Soviet-nostalgic party has dispersed. I get home to pack my things to return to Yerevan in the morning, thinking about how many Azerbaijani flags I will see again, before I cross the border.

Recently published

The EU’s Civilian Mission to Armenia Can Raise Accountability of Regional Actors

After almost three decades of remaining on the sidelines of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict negotiation process, the EU has now stepped in, positioning itself as a mediator in the Armenian-Azerbaijani conciliation process.

Read moreSurrounded by Belligerent States, the Armenian Economy Finds Security in Its Mountains

Ongoing security threats by Azerbaijani Armed Forces since the end of the 2020 Artsakh War have prompted Armenian policy makers to speed up planned upgrades to the country’s transport infrastructure. Raffi Elliot explains.

Read moreHow Can Armenia Exploit Its Innovation Potential to Become a High-Income Country?

Despite the critical challenges facing Armenia, achieving security and development, establishing strong state institutions, quality education and healthcare and a fair judicial system remain constant. Science, technology and innovation will be key to its realization, writes Ani Toroyan.

Read more