Listen to the article.

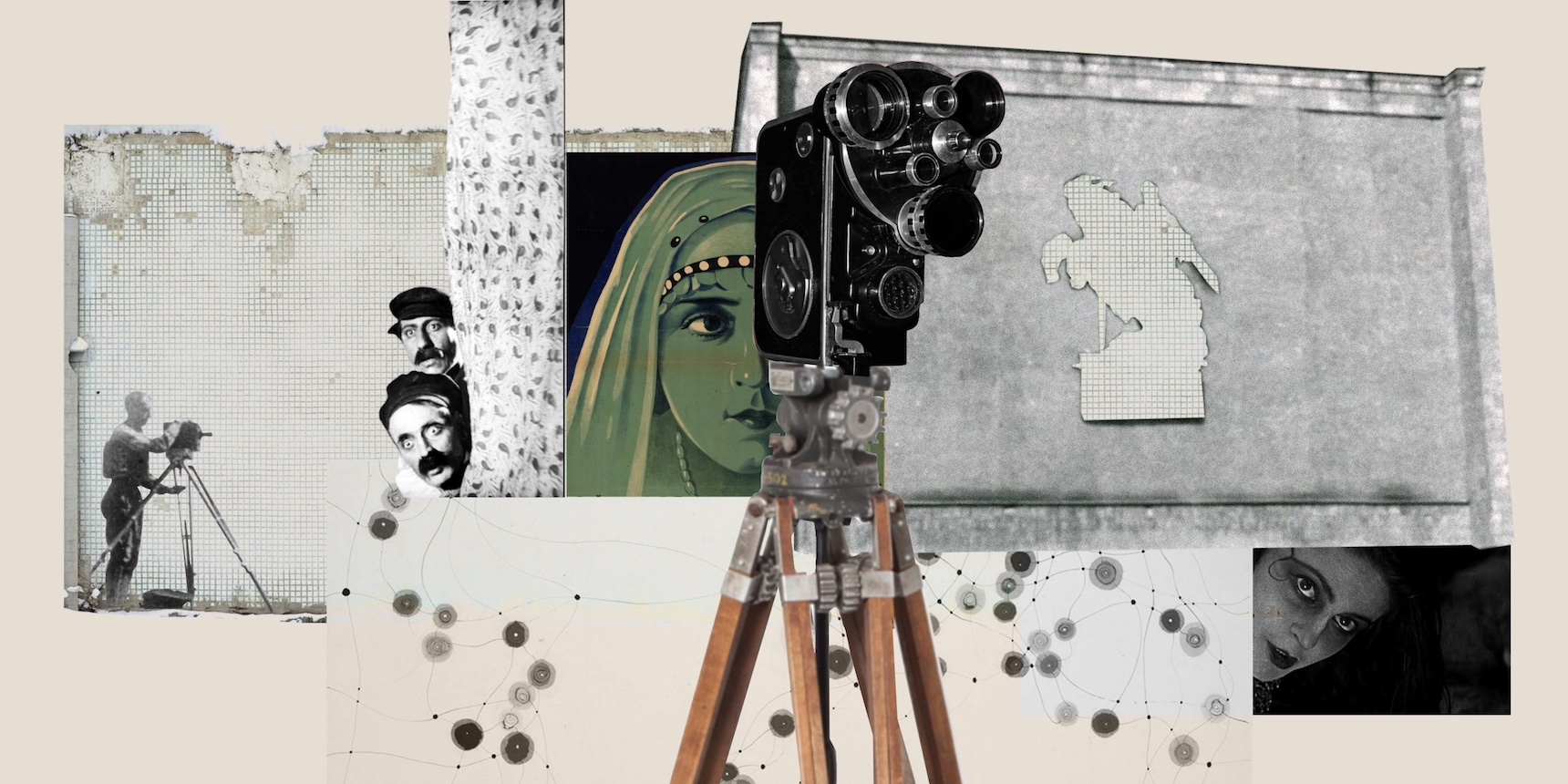

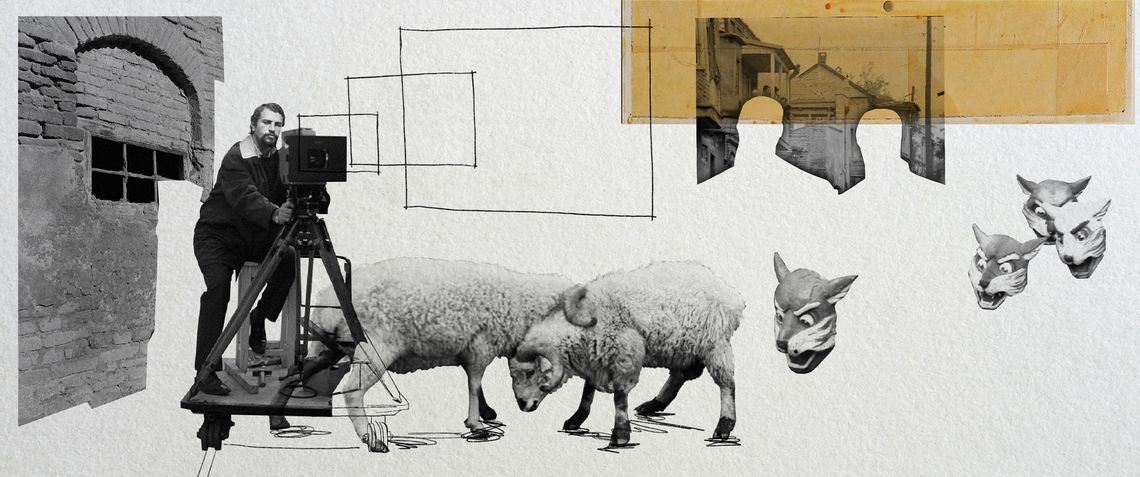

Can cinema truly change the world? Soviet officials certainly believed in its transformative power, though they mostly favored transformation in one, tightly controlled direction. “Cinema,” declared Anatoly Lunacharsky, the first head of the Bolsheviks’ cultural ministry, “is more powerful than any narrow propaganda because it imbues ideas with emotion and captivating form.” For decades, Soviet cinema obeyed this commandment with near-religious devotion: rigorously censored, aesthetically flattened, ideologically sound. It was a machine built to manufacture loyalty.

But Sergey Parajanov didn’t make films to obey.

Born in 1924 in Tbilisi, Georgia, to an Armenian family steeped in art and storytelling, Parajanov grew up in a cultural crossroads. Armenian by inheritance, Georgian by geography, and eventually drawn deeply into Ukrainian cultural life, he became a man of many homelands…and many tensions. But it was his Armenian identity that anchored him most. Even his name bore the mark of assimilation: originally Parajaniants, it had been Russified to Parajanov, a small erasure within a larger Soviet campaign to iron out the creases of ethnic difference.

Parajanov’s early films stayed within the limits of Soviet cinematic orthodoxy. A graduate of VGIK, the Soviet Union’s top film school, he turned out a few tidy, unremarkable works: “Andriesh” (1955), “The Top Guy” (1958), and “Ukrainian Rhapsody” (1961). Films that played by the rules, and were largely forgotten because of it. Parajanov later dismissed them as creative false starts. His real voice, his rebellious, poetic, ungovernable voice, had yet to find its form.

That form arrived with a crash in 1964.

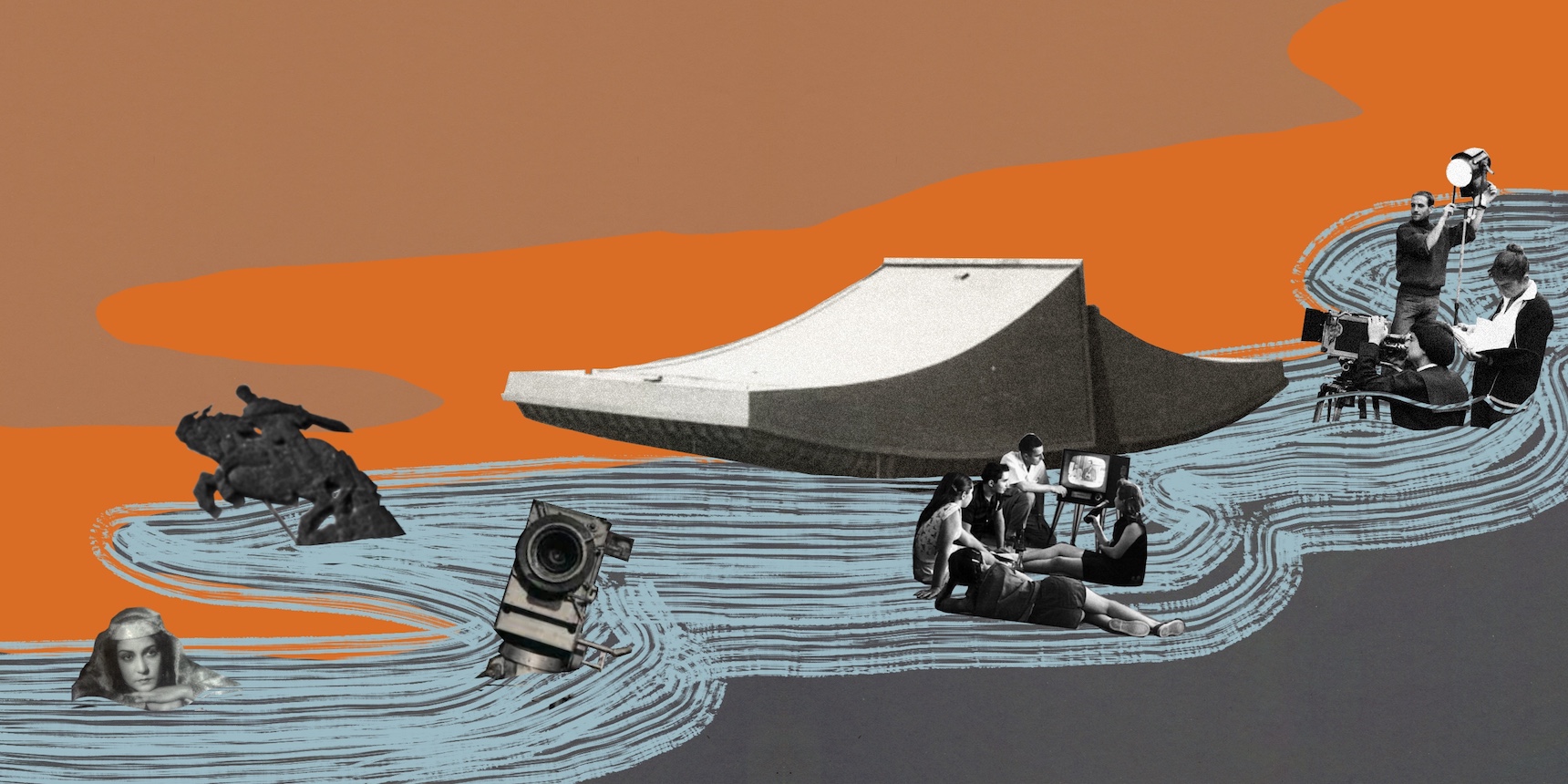

“Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors”, Parajanov’s breakthrough film, was based on a novel by Ukrainian writer Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky. It told the story of Ivan, a Hutsul villager from the Carpathians, who is haunted by love and grief. But the plot was not the film’s engine, its power came from its visual language. Shot by cinematographer Yuri Illienko, the film immersed viewers in a swirling world of ritual, folklore, pagan belief, and ethnographic detail. It was ecstatic, operatic, defiant. It spoke in the language of dreams rather than dialectics. And it spoke Ukrainian, one of the rare Soviet films not dubbed into Russian for Union-wide release.

This was no accident. The film arrived at a moment of rising Ukrainian cultural resistance. The 1960s saw a new generation of Ukrainian writers and thinkers, known as the shestydesyatnyky, or the Sixties, pushing back against the Soviet campaign of cultural homogenization. They found in Parajanov’s film something that Soviet cinema was never meant to offer: a mirror reflecting their own national identity, unfiltered and unapologetic.

One of those thinkers, Ivan Dziuba, called the film “courageously national” and recognized in it a quiet but unmistakable challenge to the Soviet myth of cultural brotherhood. At the film’s Kyiv premiere in September 1965, Parajanov and Dziuba, along with several others, seized the moment. They took the stage to denounce the secret arrests of Ukrainian intellectuals. It was a breach not just of etiquette but of political safety. The regime took note.

Parajanov, once a tolerated eccentric, became a target.

And still, he pressed forward. In 1968, he released his most daring and elusive work, “The Color of Pomegranates”. Inspired by the life of the 18th-century Armenian poet-troubadour Sayat-Nova, the film jettisoned conventional narrative in favor of a series of symbolic tableaux, pomegranates bleeding, manuscripts floating, robed figures moving in sacred rituals. It felt more like an illuminated manuscript come to life than a biopic. Parajanov’s Armenian identity saturated every frame: his devotion to spiritual beauty, national memory, and poetic form was unmistakable.

Soviet censors were baffled and unsettled. Armenian authorities claimed the film failed to faithfully portray the poet’s biography. Official memos flagged the overabundance of religious imagery. Others complained the film was “inaccessible,” “elitist,” and “devoid of clear ideology.” It was screened in Armenia but denied broader release. Abroad, bootleg copies found their way into the hands of cinephiles, where the film was immediately hailed as a masterpiece.

But inside the USSR, Parajanov’s defiance could not go unpunished.

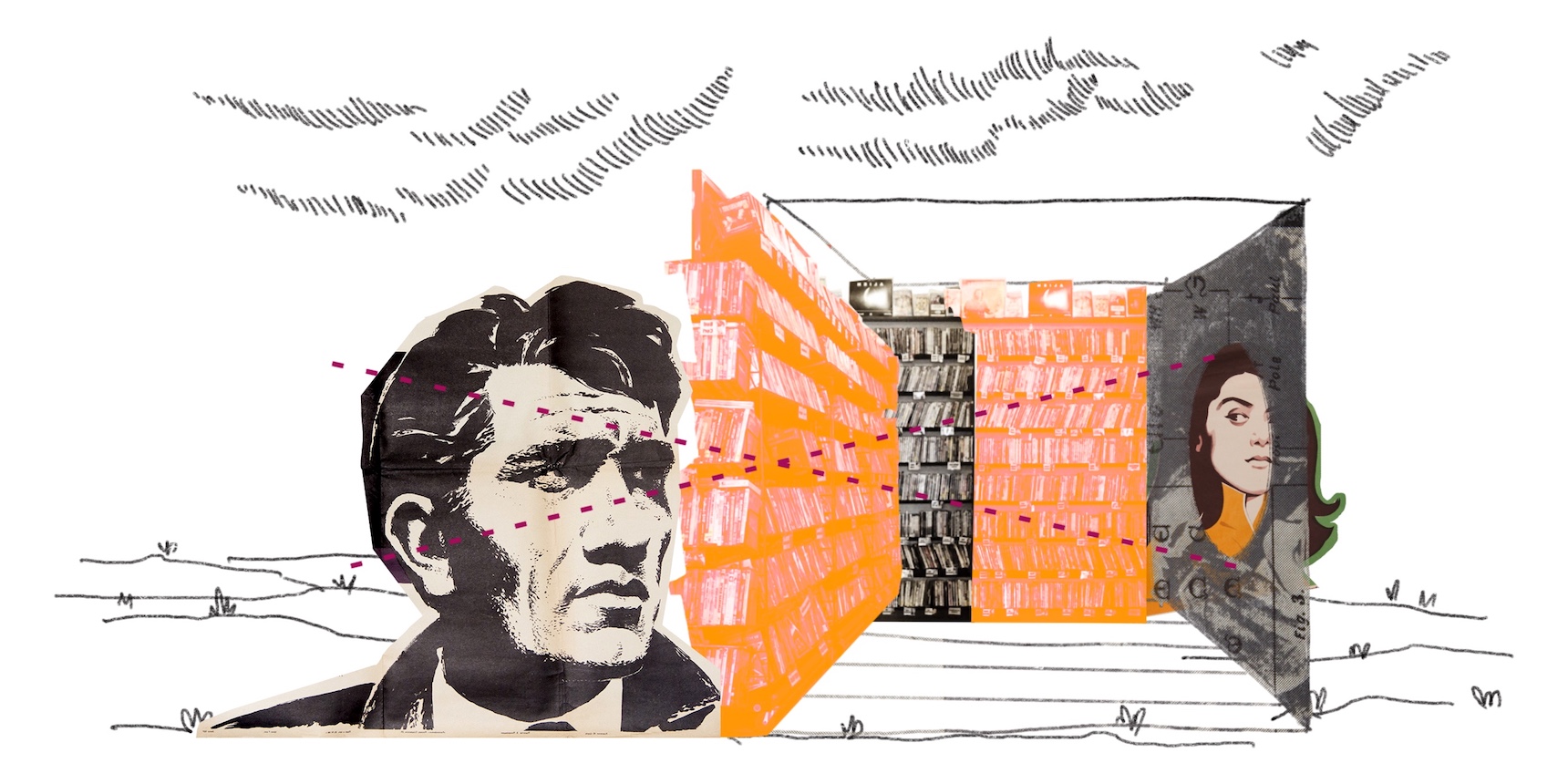

In 1973, he was arrested in Ukraine on fabricated charges, homosexual acts, “corrupting youth,” and illegal trading of icons. None of it held up under scrutiny. Everyone understood: his real crime was creating films that didn’t serve the state and defending artists who refused to bow. The punishment was four years in a labor camp, followed by years of artistic exile. During his imprisonment, he continued to make art, collages, drawings, and screenplays that would never be shot.

His arrest sparked international outrage. Jean-Luc Godard, Federico Fellini, François Truffaut, Yves Saint Laurent, Luis Buñuel, and Andrei Tarkovsky all publicly demanded his release. They didn’t just praise his talent, they positioned him as a symbol of artistic resistance, a beacon of human expression behind the Iron Curtain.

Yet even upon his release, Parajanov was never fully free. He was allowed to make a few more films, “The Legend of the Suram Fortress” (1985), and “Ashik Kerib” (1988), but the conditions were never stable. State pressure remained. His health faltered. He died in 1990, just months before the Soviet Union itself began to unravel.

So what do we make of Parajanov today?

He was not a political filmmaker in the narrow sense. He didn’t make documentaries about gulags or satirical comedies about Soviet bureaucracy. His rebellion was more abstract, more dangerous. He insisted on beauty in a system that demanded obedience. He celebrated ethnic identity in a regime that sought to dissolve it. He placed spiritual mystery and sensual texture at the center of his work, two things the Soviet project tried tirelessly to drain from art.

And that’s precisely what made his films political. They resisted not just the rules, but the very foundations on which those rules were built.

Today, Parajanov is revered across the former Soviet space. Armenia, Georgia and Ukraine each claim him as a national treasure. His museum in Yerevan is part temple, part collage, part reliquary, a vibrant tribute to a man who believed in the sacred mess of human imagination. His films are studied, dissected, and streamed by cinephiles around the world. They remain, in the best sense, difficult: visually overwhelming, narratively defiant, and formally uncompromising.

Cinema didn’t save Parajanov from persecution. It didn’t protect him from the slow, grinding violence of ideology. But it did something else, it preserved him. It outlived the system that tried to silence him. It ensured that his vision, strange and beautiful and indelibly his, would endure.

And perhaps that is what cinema can do, after all: not simply change the world, but reveal the cracks in its surface, and let the truth, however poetic, shine through.

Special selection

on the occasion of

the 103rd anniversary

of Armenian cinema

Part 1

Part 2