What drives us to watch a film these days? It may be an ad on Facebook, a tweet by a friend, a post by an Instagram influencer, or a giant billboard ad featuring Daniel Craig on a shopping mall facade. But more often than not, you’re probably enticed by an AI algorithm, which “gently” plies behavior-learnt suggestions of new content any time you may contemplate a movie night in the comfort of your home. The average viewer will not generally dwell on the fact that such targeted, machine-based marketing deliberately diffuses the possibility of spontaneous and unmediated engagement with contemporary cinema. While new media technologies create the perception that the consumer has an “infinite” range of content to choose from, the reality is that the likelihood of encountering and discovering such new material becomes narrower and tightly regulated according to what the algorithms “think” we want to consume.

Tailored for capitalist imperatives, these economic and marketing models strive to condense the targeted consumer into an easily-readable and definable supply unit. In short, the more limited our demands for variety, the easier it is for corporate conglomerates (and the tools they create and employ) to endlessly supply us with the same reheated, rehashed and repackaged material. Hence, the rise of the franchise industry in all almost all spheres of current film and television production, which dilutes and reproduces the same meager content to the point of parodic self-pastiche: witness the latest “Scream” installment or the restyling of classic films like “Fatal Attraction” into mini-series. This system of entertainment supply and distribution is not prone to deal with the fact that as a consumer of cinema, my predilections will span and veer from Czech silents, Soviet poetic cinema, American exploitation movies of the 1950s and Italian giallos, Pedro Almodóvar and Martin Scorsese to the latest films by Julia Ducournau, or Yorgos Lantimos. What the algorithm instead will try to convince me to watch is the new Jennifer Lopez action flick “The Mother”, just because I indulged in Amazon Prime’s neo-feminist remake of David Cronenberg’s “Dead Ringers” about deranged twin obstetrician sisters.

So, it’s not difficult to reach an overarching conclusion about how data-mining industries, which now fully encompass commercial film and TV distribution across the world, manipulate and flatten our attention span in order to befit a standardized production line of entertainment content. If Bruce Willis is your thing, then the market will make sure that the brand is kept alive for as long as possible by resurrecting the actor digitally, while he slowly fades away from the onset of dementia. Technological progress aside, one of the nefarious outcomes of these processes is the increasing lack of truly innovative and creatively diverse material on the cinematic scene. Though such films are still made and may even end up on specialized streaming platforms like Mubi, or the home-video pantheon that is the Criterion Collection, the audiences for non-mainstream cinema are shrinking at an alarming rate, as do the means for their production and distribution.

The situation has reached a point where major auteurs like Scorsese and Jim Jarmusch, among others, have come forth to announce the passing of cinema as an art form. Such trepidations are, of course, not new. Ever since the appearance of the “talkies” in the mid-1920s, cinema has faced some kind of an existential crisis or other, as shown in a newly-published study The Endless End of Cinema. Most recently, we witnessed a real death-scare in the form of the Covid pandemic, which threatened to obliterate the already decrepit cinema-going culture in one swift blow, only to be saved at the last minute by Tom Cruise’s fighter-jet pilot in “Top Gun Maverick”.

But the decline, or, as Susan Sontag has put it, the decay of cinema as an intellectual and creative medium is difficult to deny. Writing on the centenary of cinema’s invention in 1996, the influential critic lamented that “Cinema, once heralded as the art of the 20th century, seems now, as the century closes numerically, to be a decadent art.” Pointing out the dramatic shift in the industry with the emergence of the blockbuster phenomenon in the early 1980s, Sontag equates the end of film as an art form with the decline of cinephilia – a mode of profoundly serious, intellectually-committed engagement between the audiences and the cinema screen. Many of her claims have become painfully and patently true:

“The reduction of cinema to assaultive images, and the unprincipled manipulation of images… to make them more attention-grabbing, has produced a disincarnated, lightweight cinema that doesn’t demand anyone’s full attention. Images now appear in any size and on a variety of surfaces: on a screen in a theater, on disco walls and on mega screens hanging above sports arenas. The sheer ubiquity of moving images has steadily undermined the standards people once had both for cinema as art and for cinema as popular entertainment.”

One of the clearest, most pernicious signs of the assault of ‘disincarnated cinema’ described by Sontag is the proliferation of nondescript and formulaic film advertising since the mid-1990s. Pass by any cinema facade in any corner of the world, scroll through any streaming platform or film-news site, what you’ll encounter is the same ocean of standardized and interchangeable “artworks” that utilize a handful of primitive compositional formulas for promoting films, regardless of the latter’s character or cultural origin. More often than not consisting primarily of actors’ faces brandishing some blandly photoshopped emotion, these posters and digital adverts reduce the films to instantly-recognizable and entirely predictable commodities. The intent behind such formulaic advertising images is to grab the audiences with obvious “product value” through basic combinations of marketable elements: Keanu Reeves with a gun against the Eiffel Tower for teenage “John Wick” fans, Diane Keaton and Jane Fonda sporting airbrushed smiles and a glass of champagne in Venice for octogenarian audiences looking for fleeting assurances that romance isn’t over at 80, and so on…

The fundamental thread unifying such modern film advertising is the complete rejection of the concept that cinema could be about ideas, a critical reflection on reality or an edifying aesthetic experience. Instead, the industrialized marketing machine cements the perception of films as a “universal” diversion that will have little impact beyond a retinal satisfaction of our collective fantasies and fears.

In order to understand how drastically this corporative approach to film consumption differs from 20th century models of cinematic distribution, we only have to look at examples of film poster art from the second half of that century. Before the age of media conglomerates, the international film distribution landscape presented an infinitely more stratified and complex picture. Even the smallest of film markets, such as Armenia, had their own production and distribution mechanisms that were fitted to local needs, tastes and cultural discourses. With their competing political agendas and economic structures, each of these territories had an opportunity to make their cinema visible across a wide range of networks and distribution channels. In this ideologically-structured system, cinema was never merely a form of mass entertainment or propaganda, but a tool of cultural exchange and diplomacy.

Incorporated into a politically-dictated context, Soviet-Armenian cinema had access to a vast market, which, until 1989, was defined as the socialist block. Channeled through the centralized state film distribution organ called Sovexportfilm, Armenian films appeared on the international scene as early as 1925 with the documentary “Soviet Armenia”. This sophomore local production was commercially released not only in the USSR, but also France and the U.S. The frequency of Armenian exports increased rapidly following the end of World War II and the transformation of the world’s geopolitical landscape, as significant parts of Eastern Europe, South-East Asia and Latin America came under Soviet influence.

Magazine Issue N29

A Century of Cinema

Does it Float Your Boat? Navigating the Perilous Waters of Armenian Film Spectatorship

Armenia’s local film industry has managed to slowly bounce back after nearly two decades of stasis with an average of 25 features per year. But do these films truly reflect the realities of the people and the country that they purport to represent?

Read moreArmenian Animation: The Frontline of Female Directors

The remarkable contributions to the development of Armenian animation by female artists have yet to be explored and properly appreciated. In her latest article, Sona Karapoghosyan unearths a veritable pleiad of women animators.

Read moreDaniel Dznuni: The Interrupted Flight

Anush Vardanyan sheds new light on the inspiring and tragic fate of the Armenian film industry’s spearheading founder, Daniel Dznuni.

Read more

Left to right:

– Russia, “Fishermen of Sevan”, 1939.

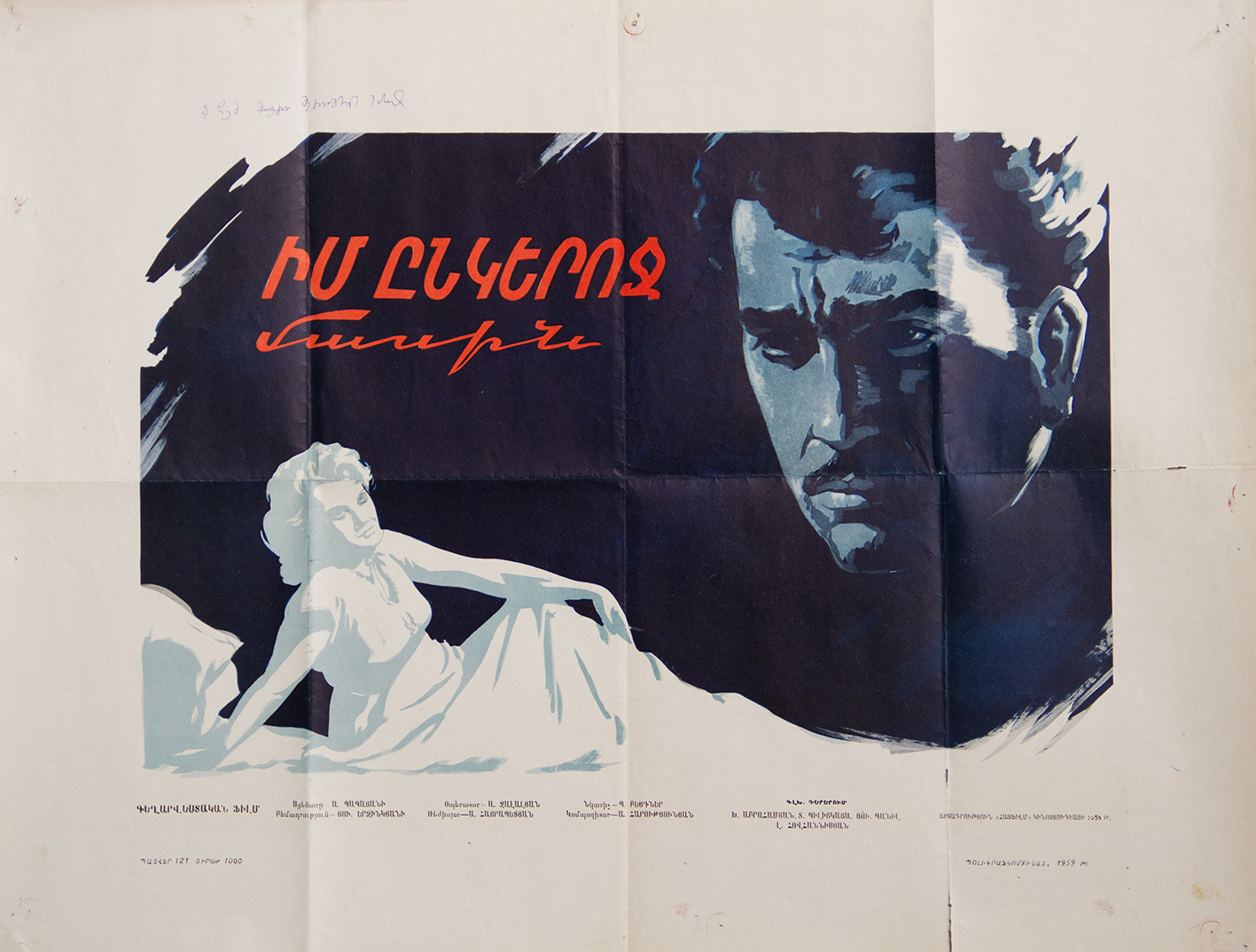

– Armenia, “About my Friend”, director Y.Yerznkyan, 1959.

Left to right:

– Romania, “A mother’s heart”, director G. Melik-Avagyan, 1958.

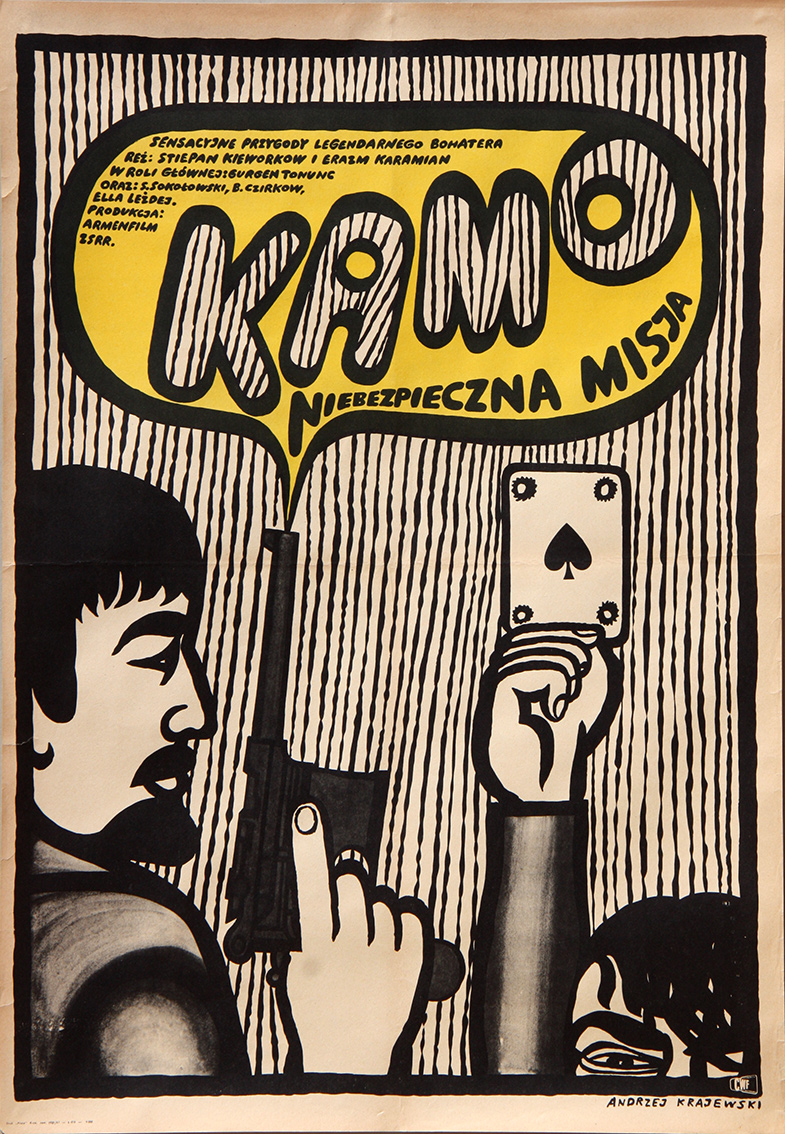

– Poland, “Kamo”, directors S. Kevorkov and E. Karamyan, 1959.

Left to right:

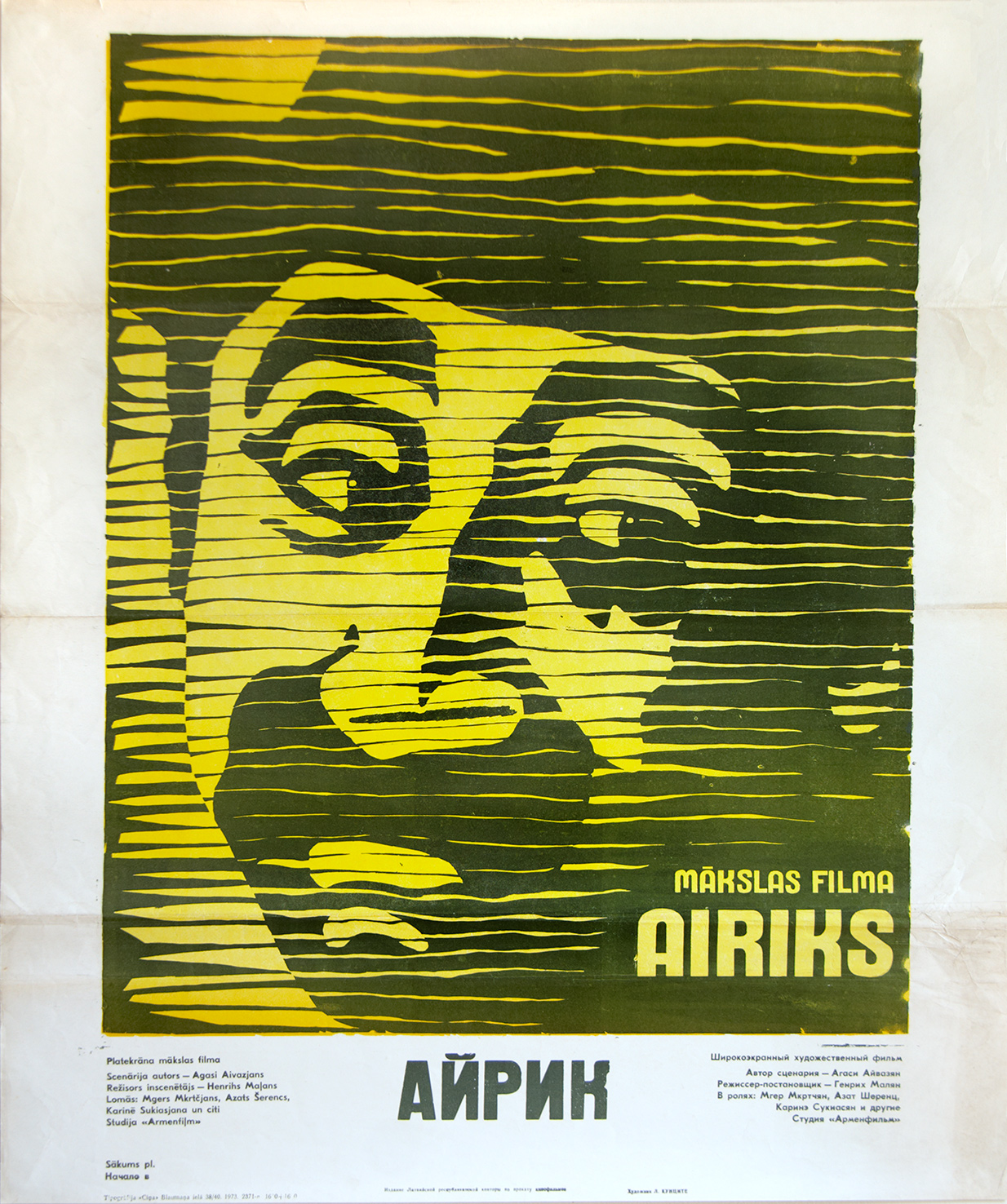

– Latvia, “Father”, director H. Malyan, 1973.

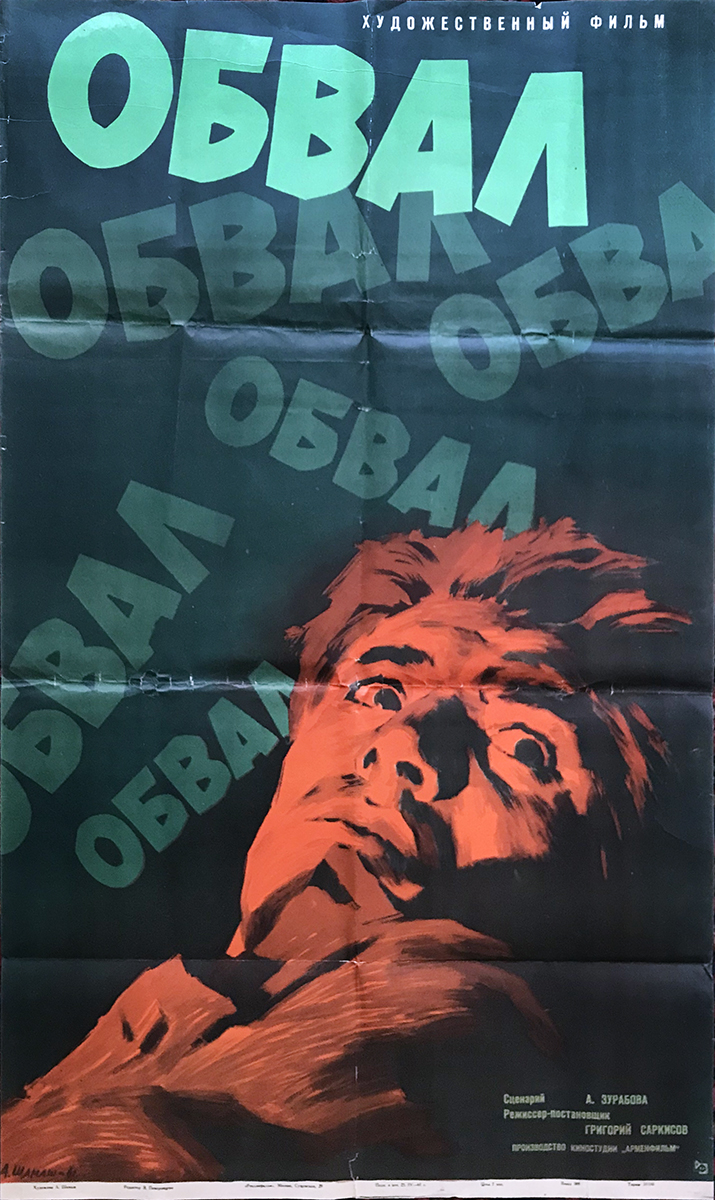

– Russia, “Collapse”, director G. Sarkisov, 1961.

Left to right:

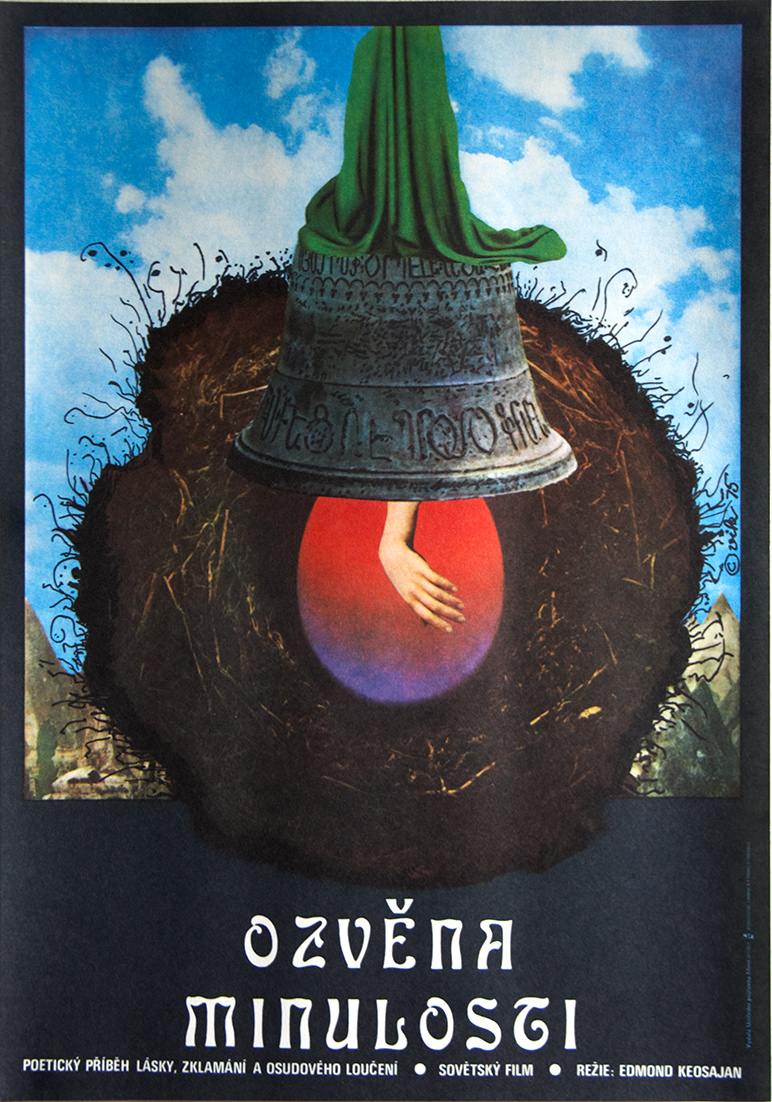

– Czechoslovakia, “The Gorge of Abandoned Fairy Tales”, Director E. Keosayan, 1975.

– East Germany, “Anahit”, director H. Beknazaryan, 1950.

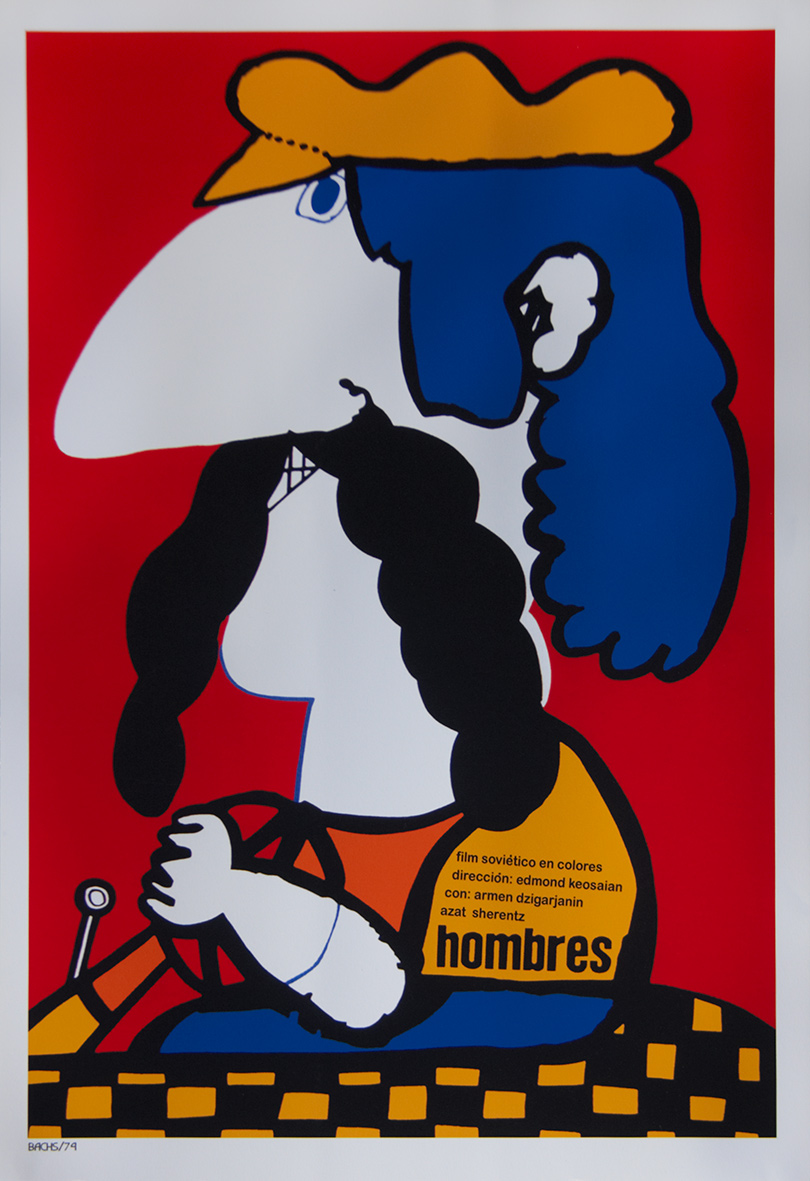

Left to right:

– Cuba, “The Men”, director E. Keosyan, 1974.

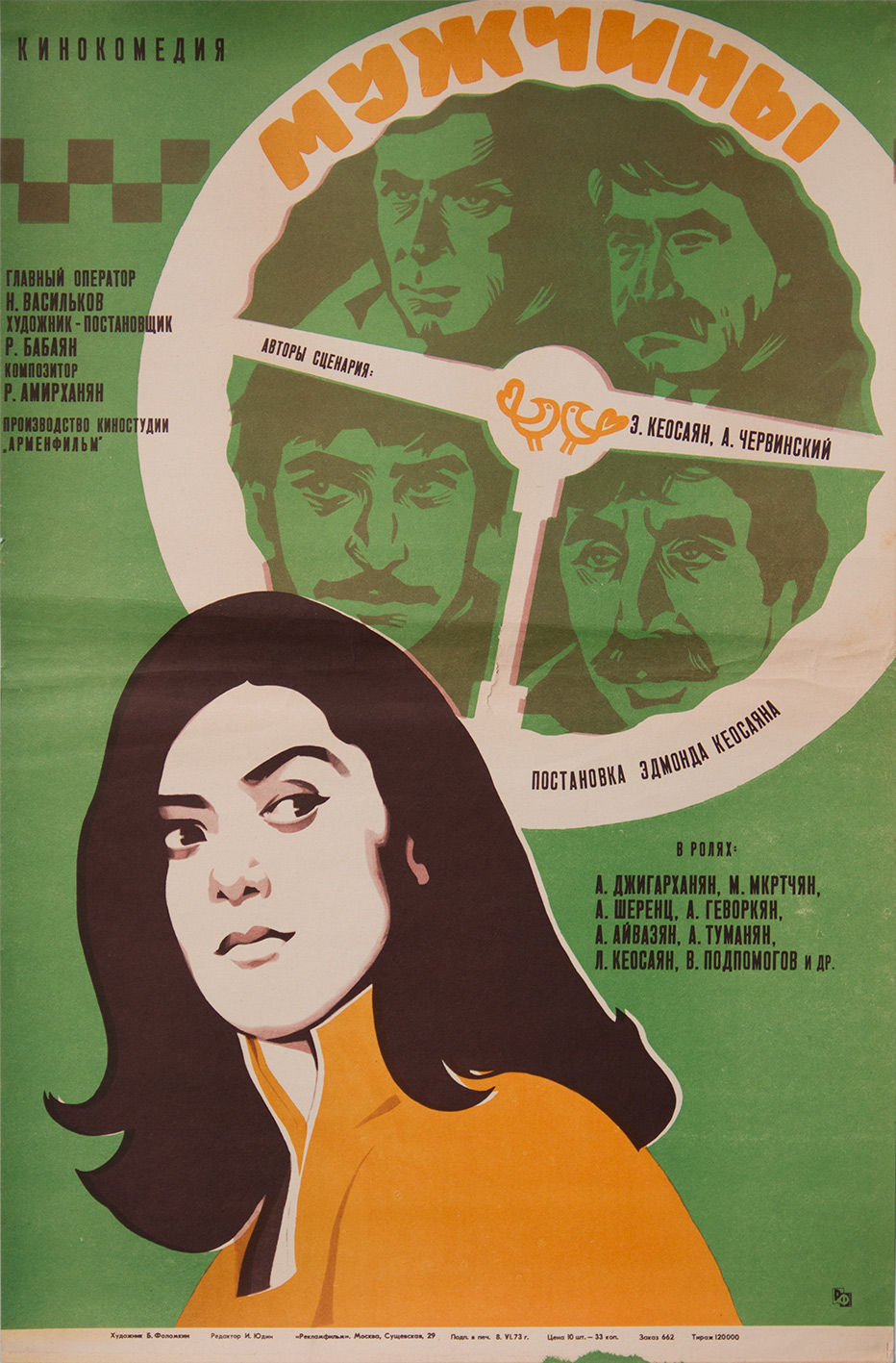

– Russia, “The Men”, director E. Keosyan, 1973.

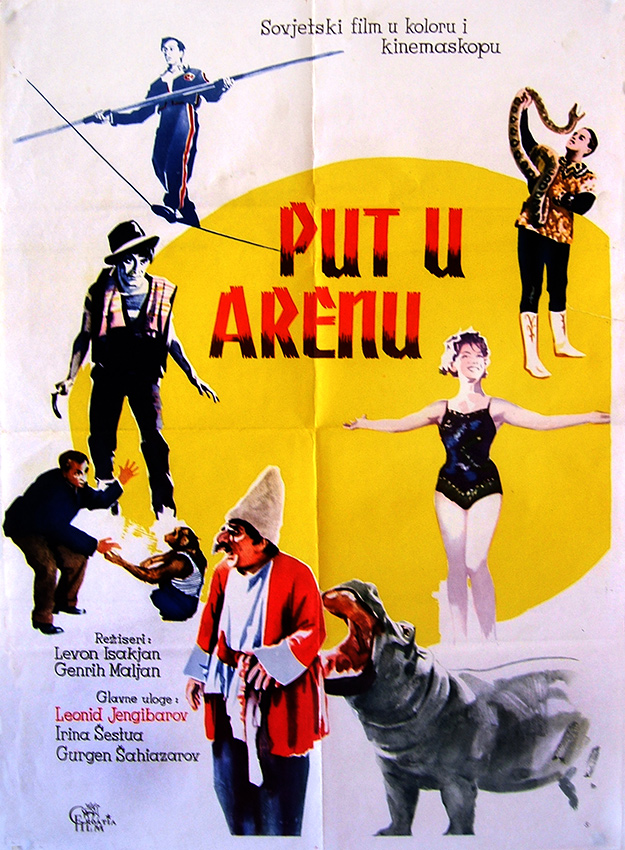

Left to right:

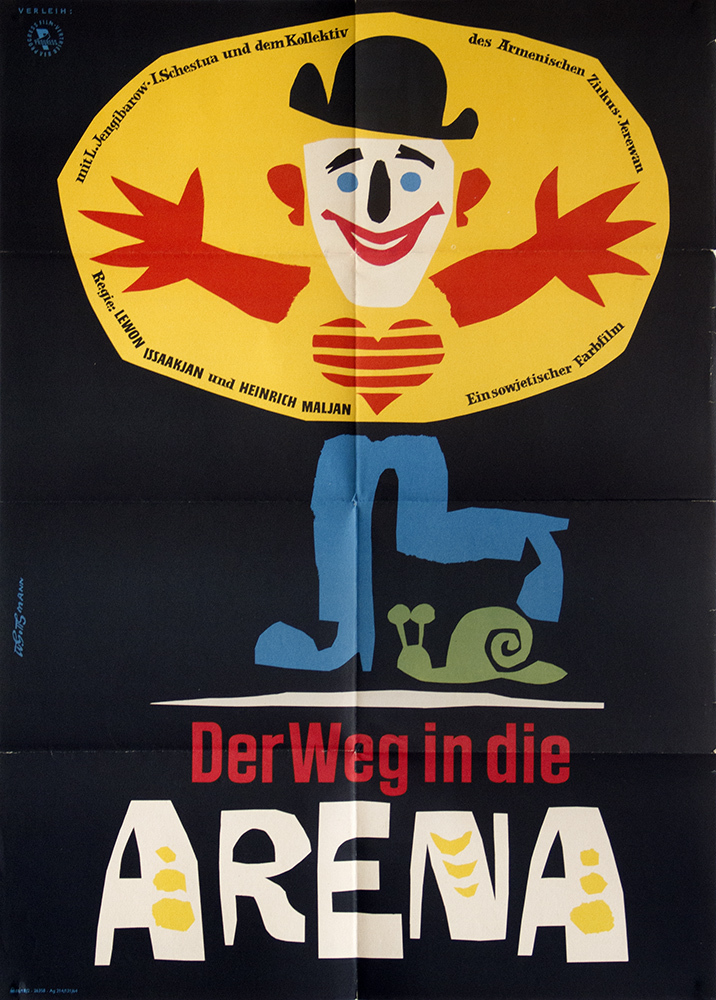

– Yugoslavia, “Road to Arena”, director H. Malyan and L. Vagharshyan, 1966.

– East Germany, “Road to Arena”, director H. Malyan and L. Vagharshyan, 1966.

Left to right:

– Latvia, “Star of Hope”, director E. Keosyan, 1979.

– East Germany, “Star of Hope”, director E. Keosyan, 1979.

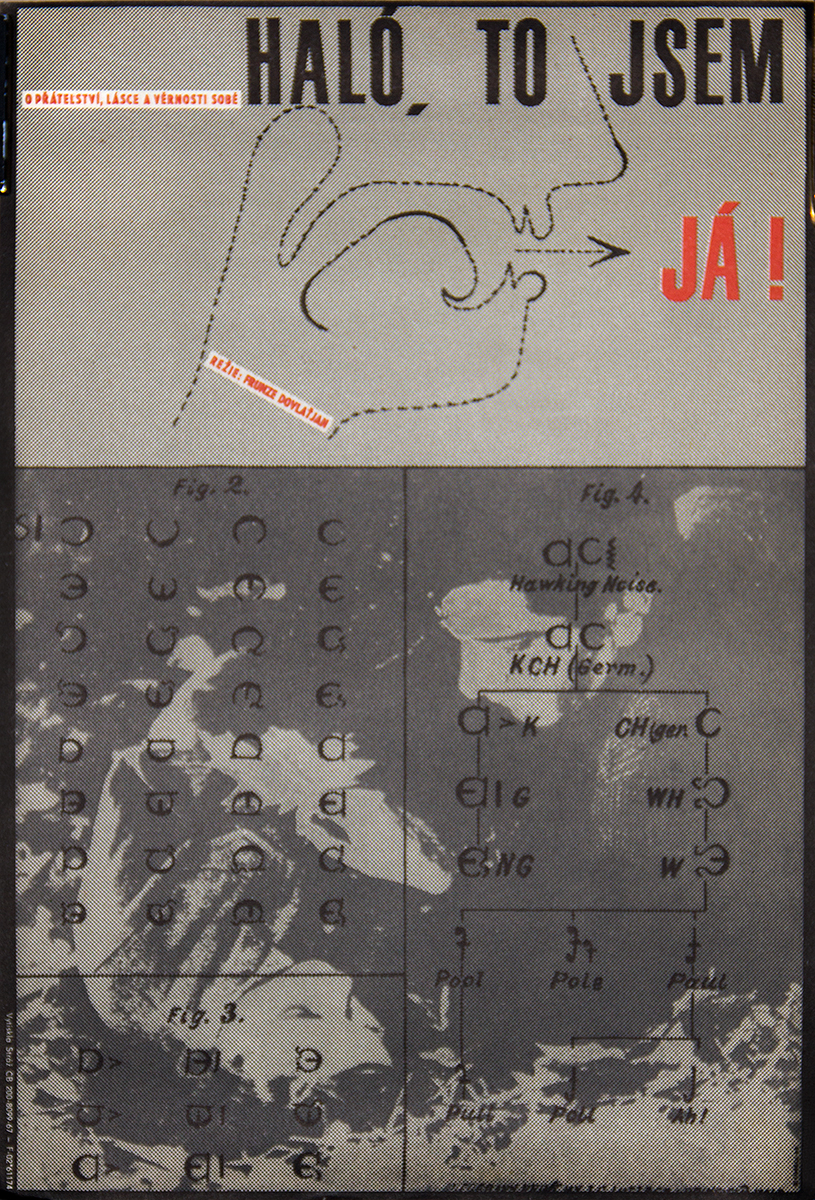

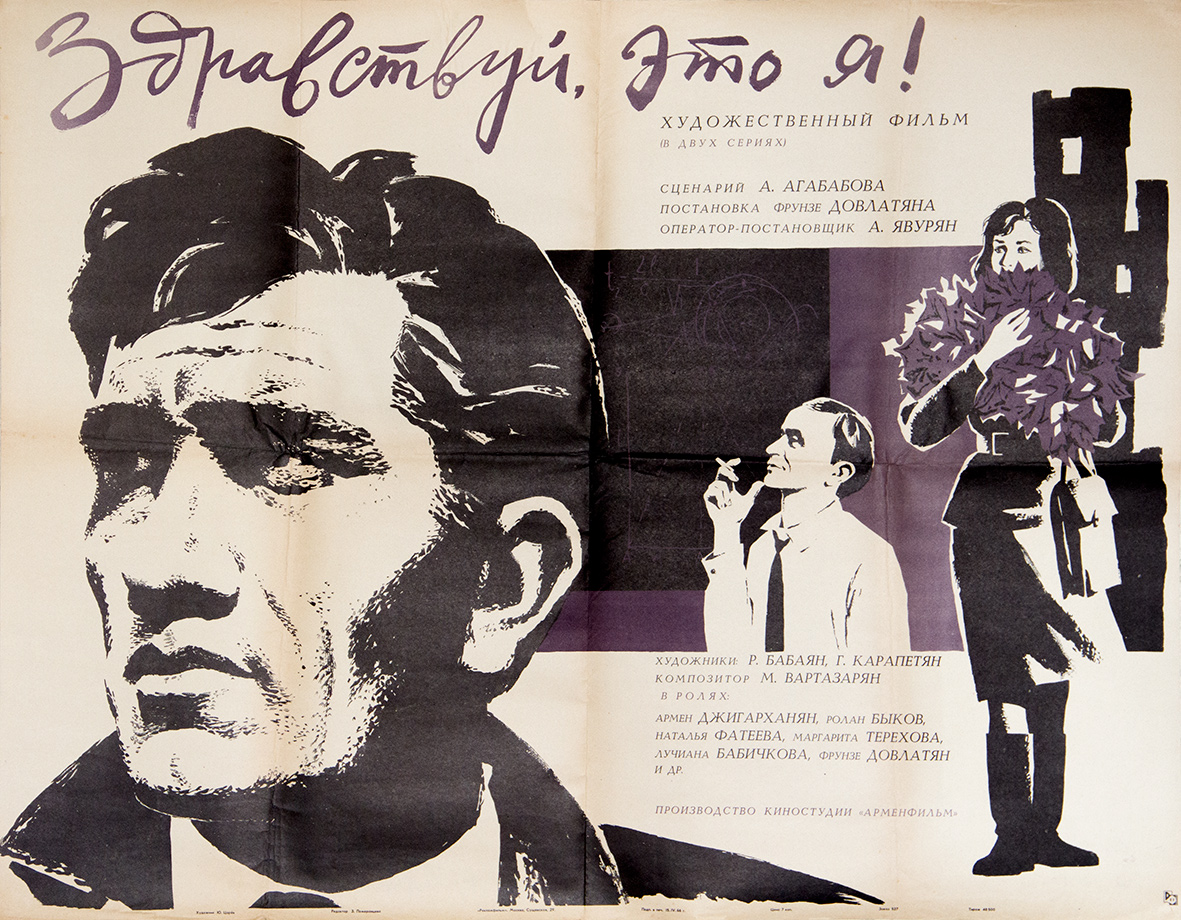

Left to right:

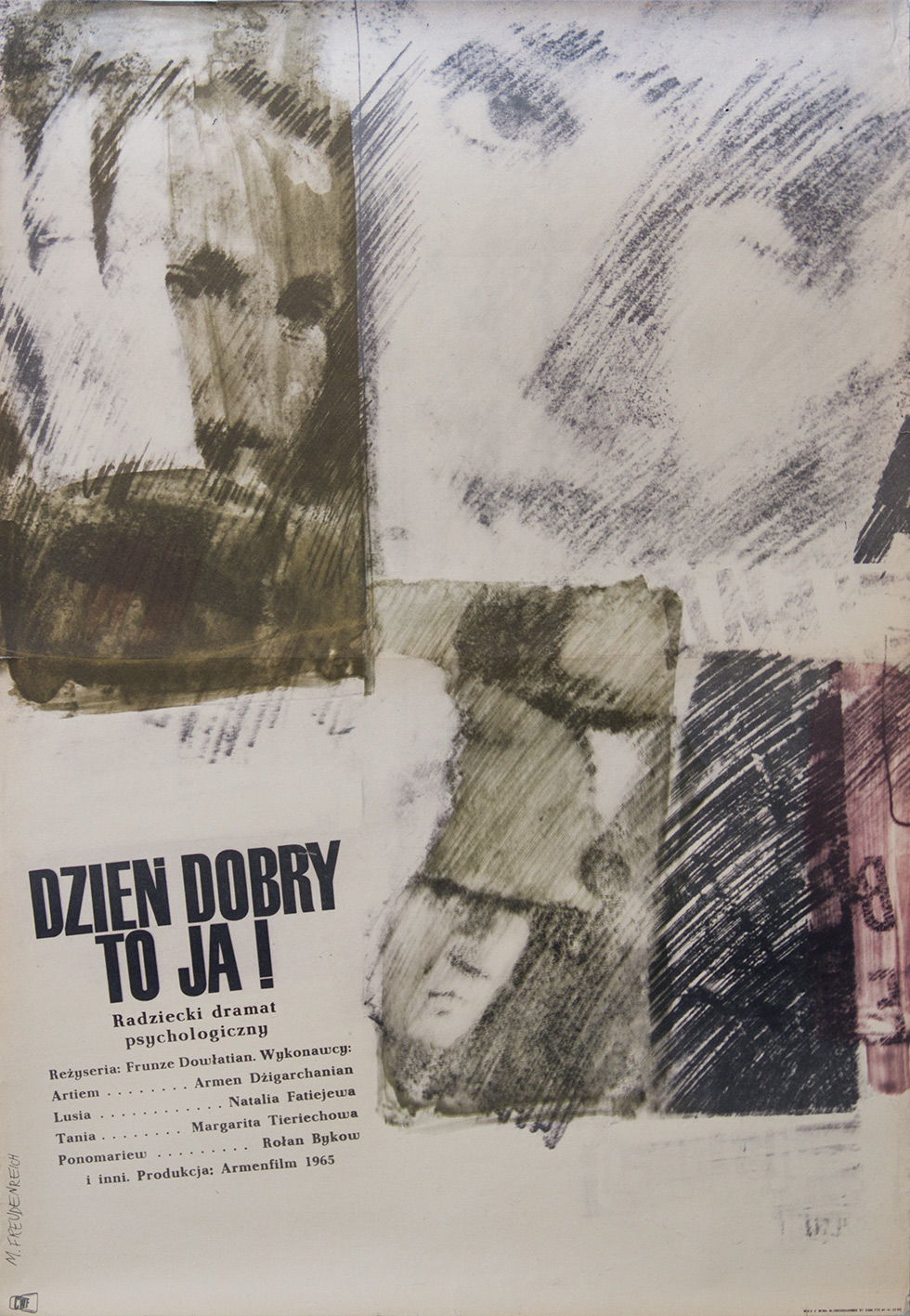

– Czechoslovakia, “Hello, its me”, director F. Dovlatyan, 1967.

– Poland, “Hello, its me”, director F. Dovlatyan, 1966.

– Russia, “Hello, its me”, director F. Dovlatyan, 1966.

During the 1960s and 70s, Armenian films were commercially released in dozens of countries, from Cuba and Vietnam to Egypt and Poland. Some films, such as Yuri Yerznkyan’s 1958 “The Song of First Love” and Tigran Kesayants’ 1973 romantic comedy “The Men”, even became some of the highest-grossing Soviet international releases of their time.

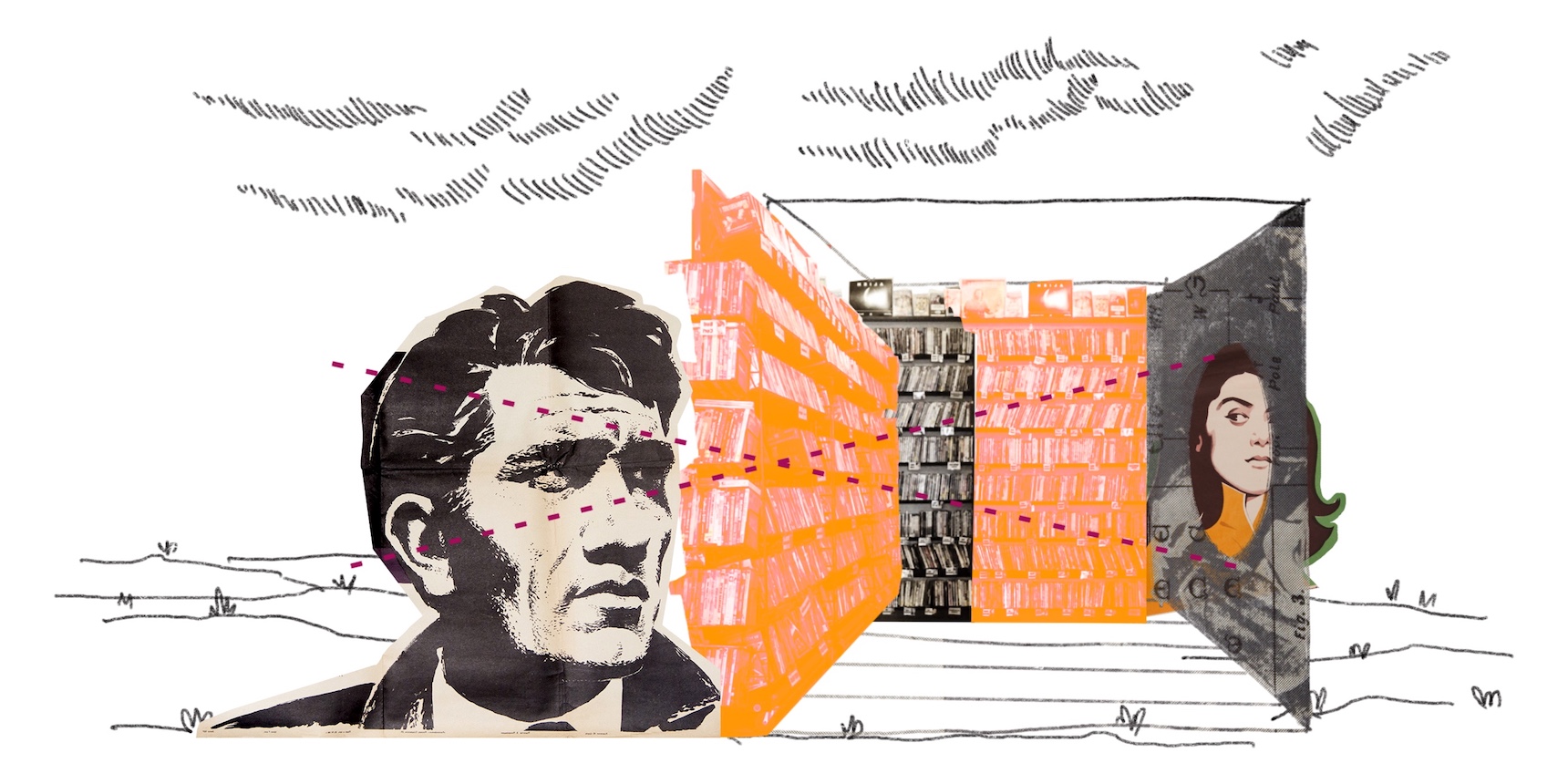

Admittedly, the production and distribution of these films was circumscribed and premediated by the ideological framework of the Communist regime. And yet, this mechanism did afford an invaluable means for cultural visibility, contact and even influence, from which Armenian cinema – and, hence, modern Armenian cultural identity – has been devoid of for over three decades. The trace of this once vibrant and active presence on the global cinematic arena is now primarily preserved in the vivid, visually striking posters that were created for Armenian films in the countries they were released in.

Putting aside the question of what Armenian films were selected for foreign release, and for what reasons, it is worth noting the incredible range of styles, design approaches and aesthetic sensibilities that these posters represent. Moreover, what these examples of popular art (for that is, in essence, what a poster is) demonstrate, is the fundamentally different understanding of the medium’s function during the 20th century. Less a means of direct advertisement, the poster acted as a visual “portal” into the film’s world. Created by notable artists, these images strived to attract the casual passerby not through marquee names or the promise of exciting storylines, but via the evocation of mood, sensory qualities and unexpected pictorial associations.

By the 1950s, every country in Europe, Latin America and Asia had developed its own, distinctive school of poster art that spoke not only about the specificities of local film distribution, but also about the particular cultural mindset that defined the reception of films in each of these territories. Poland and Czechoslovakia, for example, took the role and function of graphic design across all industrial spheres extremely seriously, and frequently competed on the international stage for pre-eminence. In their instance, the film poster was treated, first and foremost, as a medium of cutting-edge public art, and the emphasis was placed on the artistic qualities of the posters, rather than their ability to sell tickets.

Meanwhile, despite the venerable tradition of 1920s Soviet avant-garde poster art, the Russian film advertising organ Reklamfilm took a more conservative stance, carefully controlling and approving the posters for any hint of ideological digression. Nevertheless, the artists – many of whom would become figureheads of Soviet dissident art – managed to create dramatic designs that inventively recycled the legacy of Russian constructivism and futurism, in order to maximize the poster’s capacity as a form of visual storytelling.

In comparing the Polish, Czech and Russian posters for the 1966 theatrical release of Frunze Dovlatyan’s “Hello, It’s Me”, we get a telling insight into the distinct cultural attitudes that defined the reception and understanding of a given film in each of these countries. Using a monochrome, minimalist color palette, the Polish poster by Marek Freudenereich evokes the poetic and elliptical qualities of Dovlatyan’s melancholic ode to lost love. In contrast, the poster by one of the stalwarts of Czech graphic design, Frantisek Zalesak, is a visually complex and conceptual image that foregrounds the film’s philosophical ruminations on the conflict between science and human behavior. Sidestepping such layered and subtextual approaches, the Russian one-sheet by Yuri Tsarev is a more straightforward affair that draws attention to the film’s narrative elements, focusing on the presence of Armen Djigarkhanyan, who was then posited as one of the rising stars of Soviet cinema.

What we can infer from these fragments of now largely degraded practice of film poster art, is the extent to which cinema-viewing was conditioned principally as a key cultural and social custom in countries outside of the U.S. By resisting the homogenizing and despotic onslaught of America’s commercial film industry, smaller, national markets in Europe, Asia and Latin America had the opportunity to nurture local cinematic sensibilities which, in turn, contributed to the enrichment of the cinematic art itself. With the hyper-industrialization, corporatization and globalization of film production in the 1990s, such processes have been stalled and even deliberately stifled for the sake of absolute business interests, leading to a radical decline of film as a form of art and intellectual edification.

And while artistically significant and culturally diverse films continue to be produced and seen, ours is a reality in which it is no longer possible to imagine a situation in which artistically and intellectually challenging films from countries like Armenia, could achieve the kind of impact and resonance on world cinema, the way Sergei Pardjanov’s “Color of Pomegranates”, or Artavazd Peleshian’s “We” did during the 1970s and 1980s. Changing that reality today requires a lot more than growing investments in local film production. What the medium’s continual evolution demands, perhaps more than ever, is a recalibration of our understanding of film as a crucial socio-cultural experience, rather than an escapist commodity to be consumed and immediately forgotten on our way out of the shopping mall.

Perhaps the reader will be reminded of this through the original posters made in socialist bloc countries for the advertisement of Armenian films. The selection published here is drawn from the collection of over a 1000 vintage film posters held by the ManBan Visual Culture Archive in Yerevan.