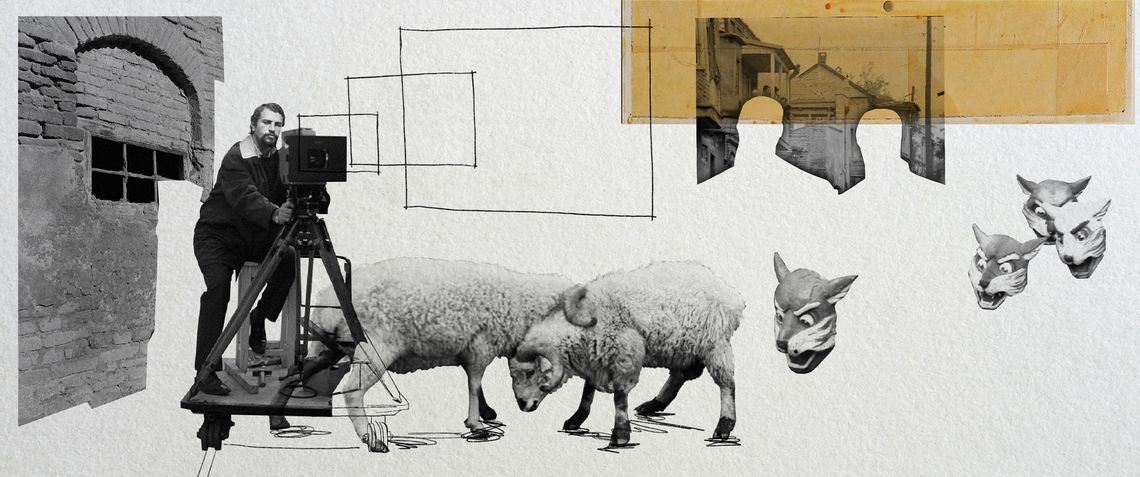

Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

When Rudolf Vatinyan suddenly passed away from Covid-related complications in 2020, just a few months before his 80th anniversary, his family and colleagues eulogized about an exacting and demanding professional who had filmed a number of iconic works of Armenian cinema – “Khatabala” (1970), “August” (1976), “Tango of Our Childhood” (1984), as well as Karen Gevorgyan’s 1991 masterpiece “Spotted Dog Running on the Edge of the Sea”. Nobody, however, remembered that Vatinyan had a parallel creative passion, one which he practiced in freedom, away from the studio’s stifling restrictions or interventions of visually-challenged directors and producers. Soon after his death, a large cache of black and white photographic negatives was discovered in Vatinyan’s apartment. Unseen for decades, these images were neatly arranged in sections in a drawer next to Vatinyan’s prized collection of antique and rare photo cameras. EVN Report has been given exclusive access to the archive, and is publishing a small part of it for the first time.

Vatinyan was born into one of the great clans that established the modern city of Dilijan at the beginning of the 19th century. Having discovered his passion for the arts at a young age, thanks to craft-making classes established by the painter Hovhannes Sharambeyan, Vatinyan soon also took up photography, learning his tropes from a local studio photographer. In the 1960s, Dilijan was one of the more culturally-active centers in Armenia, and the young amateur was able to photograph many events and foreign celebrities who had come to take part in regularly-held festivals or to stay in one of the local sanatoriums for which this resort-town was famous for.

These early attempts at documentary and street photography were accomplished enough to get Vatinyan a gig as a photo-reporter for the town’s newspaper. But the aspiring artist had bigger horizons in mind and in 1965 he applied and got into the cinematography faculty of the All-Russian State Institute of Cinema (VGIK). The reason to pursue cinema was most probably a career-driven choice. In the USSR, photography – unlike film – was a “vague” profession that did not have specialized educational institutions and was not considered a serious artistic practice, something to which Vatinyan clearly aspired to. Nevertheless, it was unquestionably the tangible merit of his photographic work that got Vatinyan accepted into VGIK – a notoriously difficult institution to get into.

Cinematographer Sergey Israelyan during the filming of Khatabala

Sos Sargsyan and Mher Mkrtchyan during the ‘Funeral’ scene of Khatabala

Immediately after his graduation in 1970, Vatinyan was hired by Hayfilm Studios in Yerevan, where his first feature-film assignment was as a cameraman on a major period piece – an adaptation of Gabriel Sundukyan’s satire “Khatabala”. Shot in color and on location in Tbilisi’s historic districts and featuring a large cast of characters, this riotous and darkly funny comedy of manners was also the biggest Armenian film production in Tbilisi since Hamo Bek-Nazaryan’s 1935 masterpiece “Pepo”. Working together with lighting cinematographer Sergey Israelyan, Vatinyan’s camera managed to balance a sense of authentic atmosphere of 19th-century Tiflis with the slightly grotesque theatricality that the play called for. The resulting portrait of the city’s multi-ethnic community and distinct traditions was remarkably nuanced and multilayered – a great achievement for a film that runs for just 70 minutes. This subtlety of approach and attentiveness towards details became a marker of Vatinyan’s style as a cinematographer. And it was a quality that was even more prominent in his photography.

Mher Mkrtchyan during the filming of ‘Gheynoba’ scene, Khatabala film shoot

Film extras on the set of Khatabala

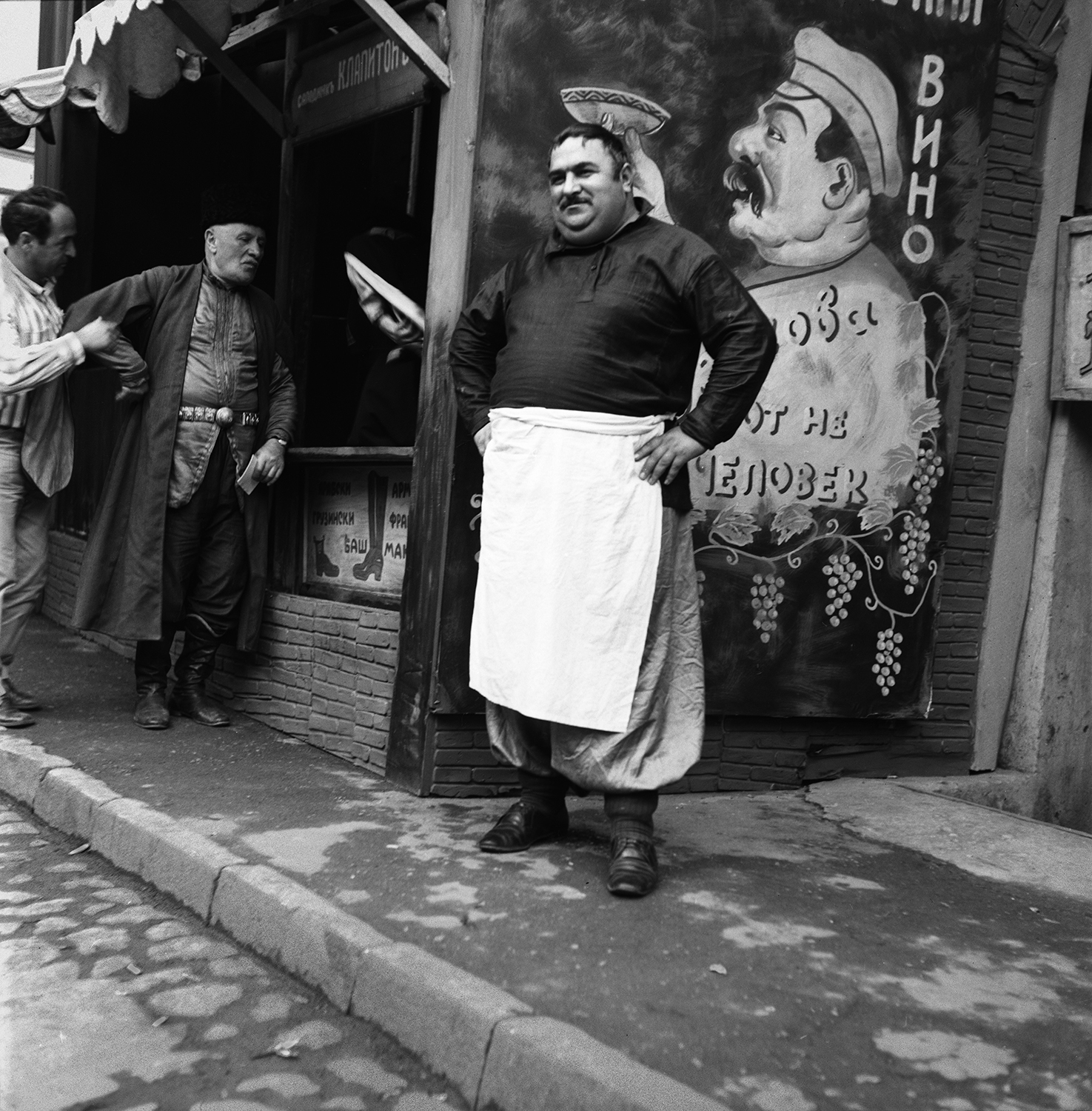

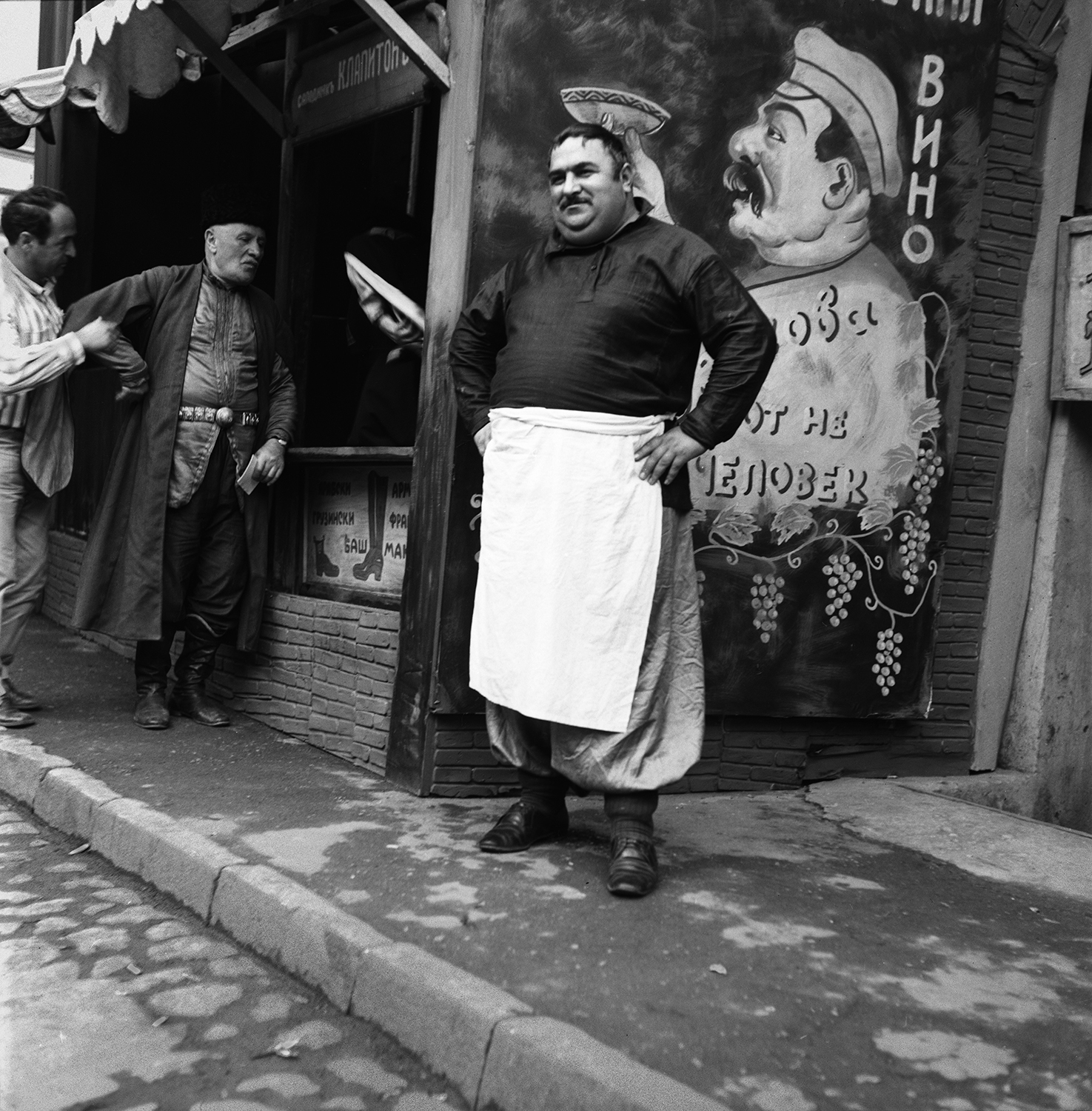

Baker, on the set of Khatabala

Azat Sherents on the set of Khatabala

Actor and spectators on the set of Khatabala

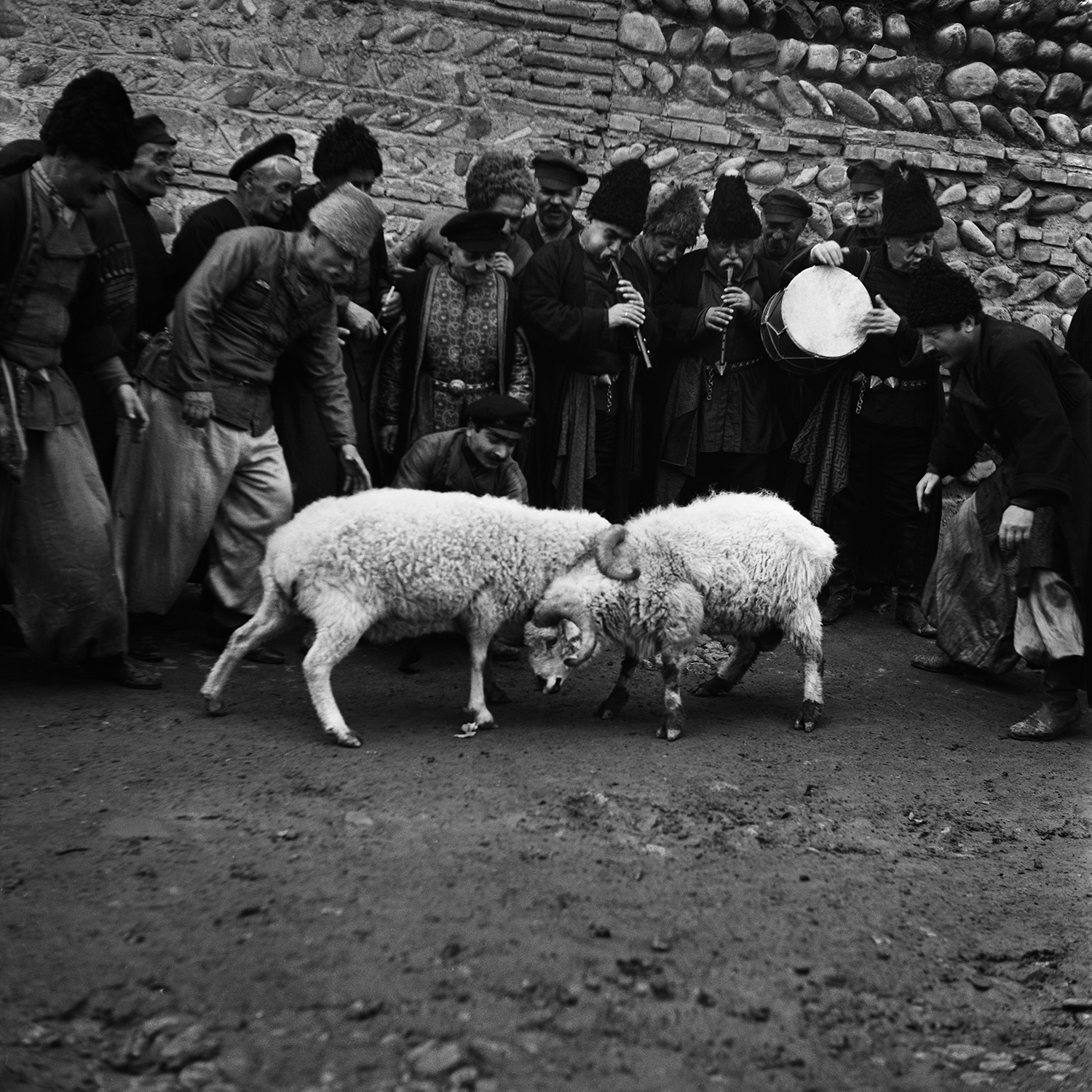

During the filming of “Khatabala” Vatinyan also shot a large number of photographs that documented the production process, the cast and the crew. Captured mostly on a medium-format camera, this black and white series shows the hand of a supremely confident and astute photographer. Combining “posed” and “snapped” compositions, Vatinyan primarily focused on the people involved in the making of the film – the lead actors, the extras, the technicians and the amazing group of artists who were responsible for creating the movie’s stunning sets and costumes. Unlike the rambunctious tone of the film itself, these photographs are infused with a mood of profound seriousness that is even solemn at times.

To have a constellation of talents such as Yuri Yerznkyan, Aghasi Ayvazyan, Sergey Israelyan, Sos Sargsyan, Mher Mkrtchyan, Laura Gevorgyan, Minas Avetisyan, Robert Elibekyan and Gayane Khachaturyan (uncredited) working on a single project was a rare occurrence. Emphasizing the importance of such an event, Vatinyan’s photographs clearly aim to represent the process of filmmaking as, first of all, an intellectual and artistic process. The gravitas of the series also evokes the overall mood of elation that empowered the Armenian cultural scene of the 1960s-70s – these portraits are not just of artists, but of icons that defined an entire era.

Khatabala film shoot. Khoy battle

Portrait of director Yuri Yerznkyan

Painter Minas Avetisyan on the set of Khatabala Tbilisi

Butcher, on the set of Khatabala

What is even more striking about this group of photographs, is the way Vatinyan bucked the tendency towards sentimental anecdotality, which was so inherent to Armenian street and reportage photography of the time. Instead, his unusually aloof style has surprising affinities with the “new objectivism” of 1960s American photographers such as Robert Frank, Robert Adams and even Diane Arbus. Not content with merely revealing behind-the-scenes dramas, Vatinyan goes beyond the obvious, to focus on the more complex relationship between reality and artifice, tradition and modernity, images and people. The space where the fantasy world of cinema and contemporary life collide, becomes a realm where the everyday suddenly appears strange and surreal – a condition that Vatinyan documented through a sharply analytical and expressive lens. What transpires as a result, is an insightful and revelatory photographic narrative about art’s function as a critical and transformative intervention into the present.

Passerby on the set of Khatabala, Tbilisi

Director Yuri Yerznkyan with painter Gayane Khachatryan and a friend

Film extra with a megaphone. On the set of Khatabala

Filming the ‘Gheynoba’ scene. Khatabala film shoot, Tbilisi

Despite the aesthetic cohesiveness and great documentary value of this and his other series, Vatinyan did not bother to exhibit or publish any of them during his lifetime. Throughout the next two decades, he continued to use the still camera on film shoots, as well as within his intimate milieu, creating a remarkable gallery of Armenia’s artistic luminaries that included Martiros Saryan, Yervand Kotchar, Hovhannes Sharamberyan, Minas Avetisyan, Armine Kalents, Galya Novents, Varuzhan Vardanyan, Tigran Mansuryan, Karen Gevorgyan and many others. A selection of over thirty of these portraits will be displayed in the exhibition “Faces of History: Portraits by Rudolf Vatinyan”, organized by the National Cinema Centre of Armenia and held at the Mirzoyan Library in October this year. The rediscovery of this wonderful legacy not only introduces us to a new name in Soviet-Armenian photography, but also helps to considerably expand our ideas about its development and history.