It’s the worst memory of my life. They twisted my arms and took me to a dingy car. The day was overcast, and everything seemed bleak. My husband stood outside and stared at me. His eyes were desolate, his face pale. My two-year-old boy was screaming and crying beside him. He wanted to run to me, but they wouldn’t let him. It was like a scene from a movie. A movie I was starring in, and they were taking me to prison.

She pauses here for a moment so I can catch my breath. I am hearing my Aunt Arev’s story for the first time. I can’t reconcile the image of her — a woman who always wears Chanel suits in Almodovar colors that she gets from who knows where, red lipstick, and high-heeled shoes — with a Soviet prison.

I stayed in jail that night. In the morning my husband asked them to move me to a hospital because I was pregnant and it was a difficult pregnancy. A stay at the hospital cost 500 rubles. It’s funny isn’t it, that they arrest you for taking bribes and then take you to a place where everything is solved through bribes, such as moving you to a hospital whether you need to or not, or having something given to you, especially food…

She was speaking so effortlessly, that it felt like she had retold and relived this story in her mind a thousand times.

Fine… Let me start from the beginning so you can understand how it happened. It looks like I just scared you, and I can tell from your voice that you’re upset [she says, laughing lightly before continuing]. “I came to Yerevan after divorcing my husband. People still condemn me for that, even today. Imagine how they felt back then. But I didn’t care. I always knew exactly what I wanted and, most importantly, I knew what I didn’t want. My father used to say that I had a rebellious soul. He used to say that about you too, remember?

She pauses for a moment, likely finding it hard to speak about my grandfather. They were very close and similar to each other. She then proceeds to make herself some coffee while continuing the story.

So I had a two-year-old son — your cousin — whom I left with your mother and came to Yerevan to find work, settle in and have him join me later. But I would go back every weekend and spend the whole day with him until I could take him back with me.

In the beginning, I worked as a professor at the Agrarian Institute where I taught Armenian Language to students in preparatory courses. After two years, I started working at the Technical Institute as Head of Human Resources in the Light Industry Department, where I also taught. By then, my son was with me and I had a new husband. We loved each other very much and we were a real family. That’s how I felt. We lived in an old, beautiful, and humble house on Atoyan Street, though we were renting it since we still didn’t have enough money.

Everything was going really well. My son loved my husband, who was an ideal partner. I was happy and worked a lot, and my director appreciated me. But they gossiped about him a lot. They said he was corrupt and a well-known bribe taker from Ijevan. His name was Mr. Ghushchyan.

The place where I worked was profitable. Factories that produced textiles and shoes were very popular, which meant there was a lot of ‘competition’ to be hired. At one point, I became a monitor for entrance exams. This was significant because of the prevalence of corruption. Often, exams that were written poorly received high marks. If someone from the ministry came to inspect these exams, they could immediately start digging through them and file a criminal case. That’s why I would review exams that were graded by the committee and had received high marks. I would then inform the director whether they had been graded correctly or not.

Every now and then, when reviewing exams, I would be flabbergasted to see illiterate writing awarded high marks. In shock, I would inform my director. However, at the time, I didn’t realize he knew very well what was happening and was being well paid for it.

Then I became a member of the entrance exam committee.

During that first year, I finally saw the truth. It turns out that, in general, no one got accepted to the Technical Institute without paying money. Everyone got in with money and their level of knowledge had nothing to do with it. They paid 2000-3000 rubles.

Let me explain it like this: everyone knew who the people were taking bribes. If someone wanted their child to be accepted somewhere, they would ask around to see whom they should approach. There was a certain list of people who worked this way a lot, so others knew where to find them and would approach them. Almost all the committee members were involved in this, but I still wasn’t. Nobody knew about me.

This is how it worked: the director would call the committee members to his office and give them two-sided pens, one side with blue ink, and the other with red ink. When grading exams for people whose names he would note, we had to use the blue pen to make corrections that would appear to have been made by the person taking the exam. Meanwhile, we had to use the same blue pen to ruin the exams of others and turn them into badly written exams. To cover his back, the director allowed each of us to bring in two people. We would keep the bribes we took from them. At first, I hadn’t taken part in all of this. However, a woman named Kima gave me 1000 Rubles from the two people she had brought, probably to stop me from speaking out.

She pauses here again as if she forgot to mention something, and then a second later she starts again more enthusiastically.

I just remembered something interesting. Make sure you write about this. There was a type of exam that they called a “tail.” These were exams that were written so poorly and with such illiteracy that the corrections made to them were very obvious. If an inspector wanted to, they could have caught all of them. That’s why, before classes started, they would call in those who had written poor exams and give them the original exams with new corrections, so they could copy them anew and it wouldn’t be obvious that someone had gone over them.

I remember that day very well. It was the end of July. I was 28 years old and pregnant with my second child, a girl. My husband had gone to Central Asia for work. I was having a difficult pregnancy, and that day it was very hot and difficult to breathe, and I had a meeting. One of the workers requested a last-minute vacation, and our director granted it without any issue. So I asked if I could take a week off as well to take it easy, and he said it was not a problem. I was so happy to be able to stay home for a while.

On August 1, when I returned to work, I discovered that investigators from the ministry had found out about the “tails” while they were being rewritten. They caught everyone, including me, and took us all in for questioning.

The inspector saw my belly and said, ‘I swear on my children, why have you thrown yourself in this mess? If you have taken part in this in some way, write a confession. Write one and take it on yourself. Whatever you have done, it will be a small crime. They’ll give you a pardon and you can go back to your family. We need to catch other people here.’

I was naive. His words affected me, so I confessed to taking 1000 rubles, but I didn’t say from whom. They detained me until midnight and then released me. Outside, my husband’s brother was waiting for me. I told him everything, and he said that what I did was really bad, and that I had made a big mistake. But I tried to convince him that what I did was right and that the investigator said nothing bad will happen. You can imagine the level of my naivety.

Let me tell you more: the other investigator told me that my director confessed on paper that I was a bribe taker and that he had suspended me for a week because they caught me taking a bribe. But I was so loyal to my colleagues and other similar Soviet attitudes that I didn’t believe that my director would sell me out. The first investigator specifically encouraged me to write a confession so they could at least arrest someone from the institute. The second investigator was more humane, a normal person whose last name was Hakhverdyan. He told me everything, including that taking a bribe was one of the most difficult cases and even if I don’t admit to it but they caught the bribe in my hand, they still couldn’t prosecute. Besides that, he told me the most severe bribery crimes are punishable by 8 to 15 years. My heart stopped at hearing that number.

I paused here to collect my thoughts and review my notes. Meanwhile, my aunt continues talking about the prison, laughing as she mentions that it was across Yerevan Lake, where, if she wasn’t mistaken, Robert Kocharyan’s current house stands.

The idea of prison was terrifying, but it ended up being easier than I expected. Everything was like the rules at Pioneer camps or in the army. The group I was with was quite good thanks to those stupid Brezhnev laws. We had film directors, accountants, and highly educated people all in the same prison… Of course, there were also criminals and murderers during our time there, but they were rather guarded.

Let me tell you about the prison. It was an area with very clean, spacious rooms, a recreational space with benches and separate areas for sleeping and working. They assigned me to knit towels with a machine. I was a laborer and quickly became the most exemplary, with letters of commendation. I got along with everyone, and they came to me for advice and help. I kept myself busy to make the time pass by quickly. One day, the prisoners elected me as chair of our brigade’s council giving me a ‘position’, she adds, laughing. She then lowers her voice, “Only my son was badly affected, my son and husband. One day the warden said, “Your husband is suffering more than you. He won’t leave the outside walls of this prison…

Do you know what was awful? Amnesty could be given to murderers, but not to people like me. Bribes were considered the worst crime, even though bribery was everywhere during the Brezhnev years. It was widespread first and foremost in his own system.

Anyway, I don’t want to talk your head off. During a portion of my imprisonment I worked as a laborer. But for the other portion, I was sent to Siberia, specifically to the Kemerovo Oblast. They gathered us all and we set off.

That road was the most terrifying thing I have ever experienced. The journey took one month, dropping us off at different locations, and sometimes, my child, there was nowhere to sleep. They would literally force us to sleep standing up. But you know me, I didn’t care what they did, I would lie down, cover myself, and sleep. One night, we stayed at the Baku prison, and the other nights in Rostov, Chelyabinsk, and Novosibirsk, until we finally reached our destination. They would take people with their hands handcuffed behind their backs, pushing the men to their knees. They followed us like dogs, watching our every move with guns in their hands, even when we went to the bathroom, we had to leave the door open.

They didn’t treat people like humans. They treated them like animals.

Finally, we arrived. There was a farm where different types of work awaited us. They suggested that I work as a milkmaid in the cowshed, claiming it was easy work. I had never seen a cow in my life. I was scared and disgusted. They showed me how to milk a cow, but I couldn’t do it properly, and my fingers hurt and became swollen.

There was an Armenian man there who told me to claim that I was sick so they would give me lighter work. I followed his advice, but it turned out that it also involved paying money. I managed to find some Rubles and gave them to the doctor. I was very scared that he would misunderstand me. But I didn’t care anymore — I was tired of both the system and its fake conditions. I received my papers, but it turned out that “light work” involved breaking ice with iron or sawing wood. I didn’t even attempt it; it was foolish to do so in that cold.

I asked around to see if there was any work I could do to stay and spend my last years there. A technician named Lidya Aleksandrovna — a beautiful woman who lived in a nearby village — told me to register as an insemination technician. It was easy work and she was going to teach me how to do it. I thought it strange that artificial insemination of cows could be easy, but I trusted her completely. And she was right, I learned everything very quickly.

There was a bull named Champion that I raised since he was a calf. Everyone was scared of him because he was the most aggressive and largest of them all. But I wasn’t; it was as if he was my student.

It was strange work. I had to work with the bull to help him mate with the selected cows. Sometimes I even had to encourage him.

In Russian, I would say, “Look at how beautiful this little cow is…” It was funny. Everyone said that the bull I raised was a gentleman. After mating with his cows, he would walk them back to the cowshed. He would get angry when the milkmaids ushered them in by whipping them and even tried to attack them several times because they hurt his cows. I had to hold him back. If I hadn’t, he would have gored those people.

One time when I wasn’t nearby, my Champion became angry again, but there was no one nearby to rein him in and stop him, so they killed him.

My Champion was slaughtered for a meat processing plant.

And just like that, my time there passed by unnoticed until one day someone from our group suggested that I write an appeal for a pardon. They even offered to write one for me. I agreed to write the letter, but said I didn’t believe they’d grant me a pardon. I thought that maybe my sentence could be shortened. They didn’t agree and insisted Iimagine that my appeal wouldn’t be denied and write the letter with that attitude in mind. So, I wrote the appeal without any hope. My acquaintance read over it and added a sentence at the top: “I want to raise my son.” The letter was sent.

About two weeks had passed when an Armenian man came into the courtyard yelling that I had been released. He spoke in such a confusing manner, I didn’t understand anything, but I didn’t believe him. Of all the letters they received, I highly doubted they would have read mine, let alone responded to it and granted me a pardon.

I went to the administration. The head there was Chiplakov. He was seated in a long room, at the side of the table, just like how Putin sits during his speeches today. I went in and asked what was happening. Without raising his head, he said that I was free to go. I still didn’t believe him and started to cry out loud, almost yelling. You know I don’t cry, but this time I couldn’t hold it back. He got up, held me, and said, “Arevik, Arevinka, you’re free. They really let you go.”

Look, I was the typical grade-A student. I was the Komsomol secretary for our entire school, class president, and president of the student council. I was the grade-A teacher’s pet that you dislike so much. There are many pictures from our school where I’m always standing next to the principal.

Back then, I thought I was a good representative of the Soviet system. Now I know that I was a victim of that system, brainwashed. And as long as we remained that way, the system was strong.

And that, my child, is how that part of my life came to an end and I came home.

I couldn’t find my house. It was somewhere else now. I struggled to navigate the city, which had also changed over time.

My sister and son met me near the lamp factory, and we made our way to our new house.

I knew that no matter what I did, I had to do it quickly. I wasn’t returning to complain or pick myself apart piece by piece. I returned with an intention to put everything back in its place and I had no time to waste.

A week later, I started looking for a job. The only place that accepted me without any additional problems was the Shustov Wine Combine. A fascinating period began for me; and the Soviet Union was already in convulsions…

But why don’t I tell you about this other part of my life next time? I’m tired of talking, and you’re a terrible listener, you fuss and cry… it’s just a story… it’s already been lived and completed, there’s nothing to be upset about. Just listen.

*All names, locations, and characters are real, only the name of the main character has been changed

Also see

Armenian Attitudes Toward Science and the Soviet Legacy

Armenia’s scientific sector was decimated in the 1990s. Many in the country have been talking about its former glory for 30 years with pride, anger and longing. What were the priorities of Armenian science during the Soviet years and what is its potential today?

Read moreArmenian Attitudes Toward Work and the Soviet Legacy

The popular opinion about the hardworking nature of Armenians changed after independence, when Armenia was left to become the master of its own destiny. Mikayel Yalanuzyan examines the Armenian work ethic.

Read moreCaricature: From the Soviet Era to Independence

Political caricature was an inseparable companion of the newspapers that were being formed under the new freedoms of speech and the press of independent Armenia.

Read moreRediscovering the Body: The Painful Birth of Post-Soviet Performance Art

Although performance art has practically disappeared from the contemporary art scene as an autonomous medium, early practitioners had a profound impact in changing perceptions of the body in Armenia’s post-independence culture.

Read moreBack to the Future: The Evolution of Post-Soviet Aesthetic in Armenian Fashion

The Armenian love for following trends is something that is a part of the collective cultural and political history. And that tendency became stronger after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Read moreFrom Censorship to State Sponsorship: The Fate of Jazz in the Soviet Union and Armenia

Jazz and Armenia have a complicated history. From its early beginnings under Soviet rule to contemporary interpretations of jazz, the genre is part of the fabric of Armenian cultural life.

Read moreNotes From a Future Museum: Bagging Up Ideologies

How a black evening handbag found among countless items in Yerevan’s largest flea market revealed a paradigmatic shift from the egalitarian criteria of Soviet ideology, which accorded functional objects with purely practical properties.

Read moreNotes From a Future Museum: The Aesthetic Politics of Armenian “Chekanka” Art

Hybridizing fine art and mass culture, Soviet-era “chekanka” art generated an unconventional visual world in which ancient and modern mythologies, as well as sexual and political desires could be blended into a patently local cultural narrative.

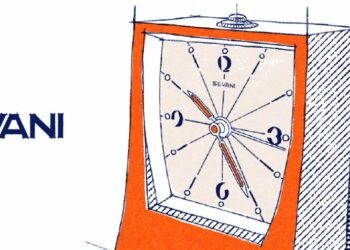

Read moreNotes From a Future Museum: Time-Keepers

Vigen Galstyan explores the humble charm of Soviet Armenian mechanical clocks in this first instalment of a series of articles about Armenia’s not-too-distant past as a major producer of everyday consumer goods and a hot spot for industrial design in the USSR.

Read more