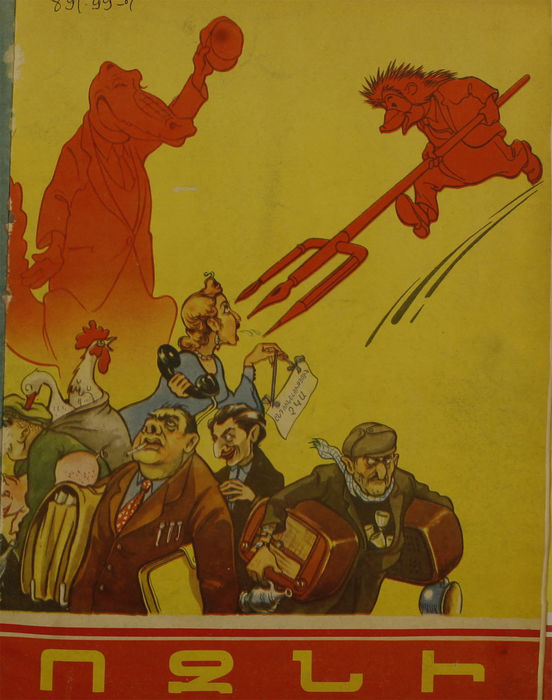

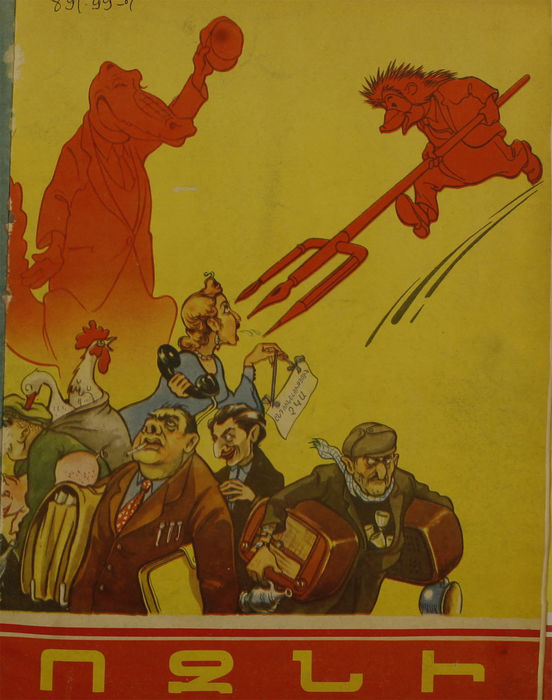

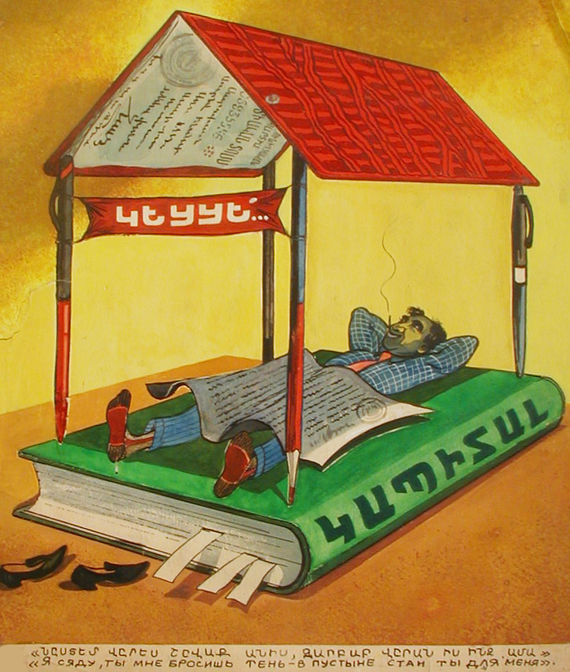

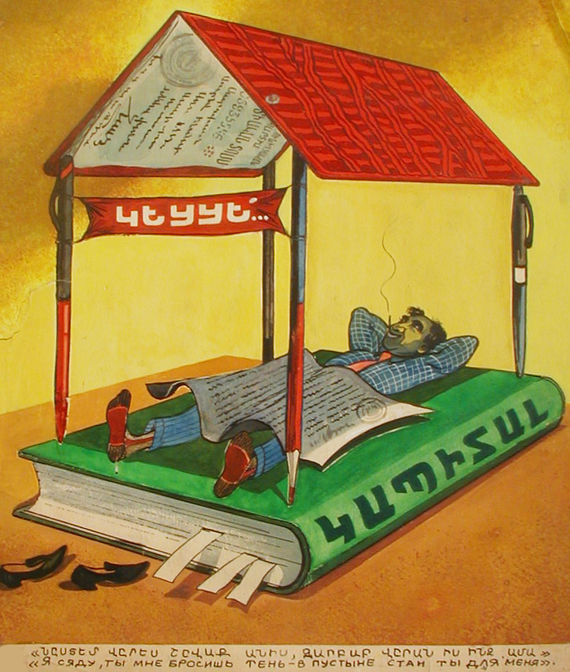

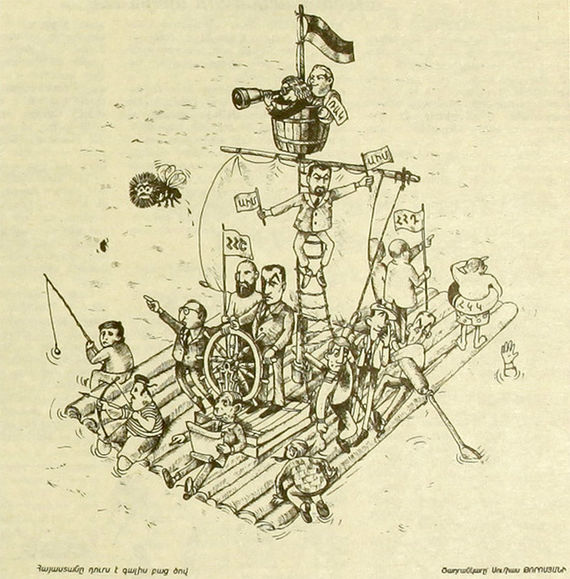

Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

The history of political caricature can be traced back more than 250 years. Transforming from its early days of artistic explorations to a significant medium of commentary, political caricature takes serious issues and presents them in a humorous and satirical manner. Starting from the mid-18th century, political events, figures and monarchs were often portrayed in caricatures, making the cartoons socially acceptable and thereby effective. The Armenian press also has traditions of caricature. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Armenian satirical newspapers such as Meghu, Tsakhavel, Mimos, Kiko, Makhlas, Sev Katu, Leplepichi and others were published in different corners of the world. In addition to satirical magazines, newspapers and magazines were rich in caricatures.

It is impossible to talk about the political caricature of the Armenian press during the first years of Armenia’s independence in the early 1990s without delving into the satire and humor of the Soviet times. People do not like criticism, whether it is in the spoken word, an article or a hint. More often, they are insulted and offended by a caricature and its author.

Architect, artist and Honorary Artist of the Republic of Armenia Ruben Arutchyan says it’s difficult to define or understand the limits of humor, satire and ridicule. “Humor, like satire, seems to exacerbate a situation,” Arutchyan says. He goes on to explain how in the Soviet era many people would buy Literaturnaya Gazeta[1] specifically for page 16, the last page of the publication. “The caricatures of Peskov, Slatskovsky and Tesler were published there… They were wonderful caricaturists…they were known for their style and they received awards abroad. Why? At that time, in the 1960s, people talked in their kitchens; they wanted to do something, and they wanted to ‘get rid of something,’ to come out, at least verbally,” Arutchyan explains adding that the caricatures had hidden meanings and all those who were intuitive were able to “read between the lines.”

There was a second, hidden thought in Soviet caricature, often difficult to understand. The authors knew that they had to draw in such a way as to ensure that the powerful censorship of the USSR would not create an obstacle.

Krokodil,[2] a famous Soviet satirical magazine, which first began publishing in 1922 featured works by Mikhail Zoshchenko, Ilya Ilf, Yevgeny Petrov, Alexander Mayakovsky and other famous writers during different times. “Krokodil…was official, where you could not do much. But the 16th page of Literaturka[3] was freer,” Arutchyan says. “For example, Zhvanetsky[4] was published there. And it seemed like we were being offered satire and humor, but in reality there was a hidden message that people like us noticed. It seems the authors were defending themselves by saying that this is humor and does not carry anything unwarranted. And the inspector probably thought that it was humor…”

Do Not Argue With a Humorless Person

Arutchyan says his father would often say that if you meet a humorless person, don’t argue with them: “Turn around and go. One day they will do something to you.” He says humor is the pinnacle of human thought: “I have categorized my friends; I have left those who do not have humor. If they do not understand humor, then, frankly speaking, they are not smart.”

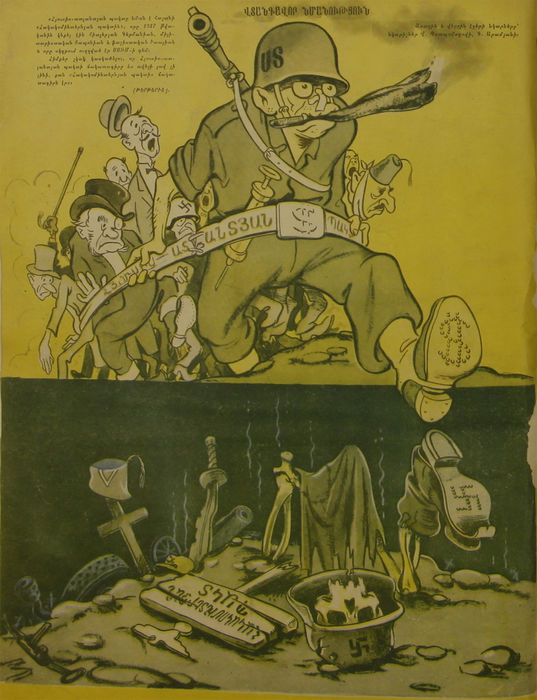

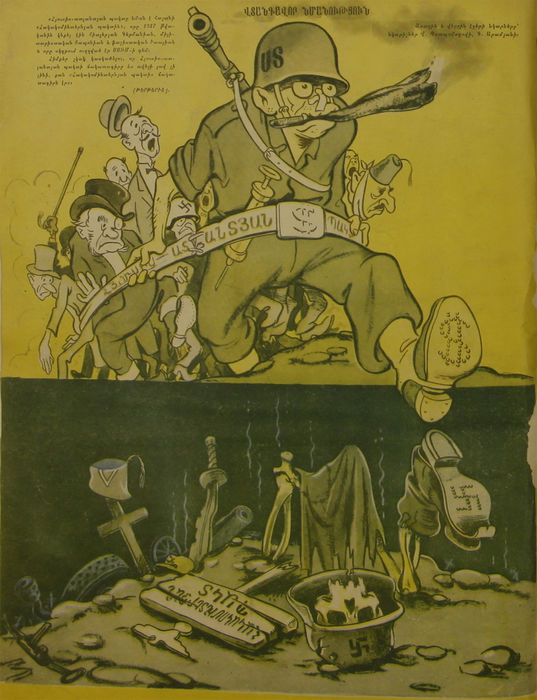

The Soviet Union was a closed, ideological system, where everything or almost everything was controlled, but at the same time, Krokodil and Litgazeta were being published under that very system. Why did the Soviet leaders allow that satire? Were they letting the steam out? Arutchyan says it was to maintain power by proving to the whole world that the socialist system was the best. “Therefore, we would look west and criticize everything that was going on there, for example writing ‘Pepsi-Colitis’ instead of ‘Pepsi- Cola.’”[5]

There were social practices that were criticized, such as bribery, but only in the lower echelons: the shopkeeper was inaccurately weighing or selling a product “under the table,”[6] construction materials were being stolen from a warehouse or workshop, etc. However, high-ranking officials were never mentioned.

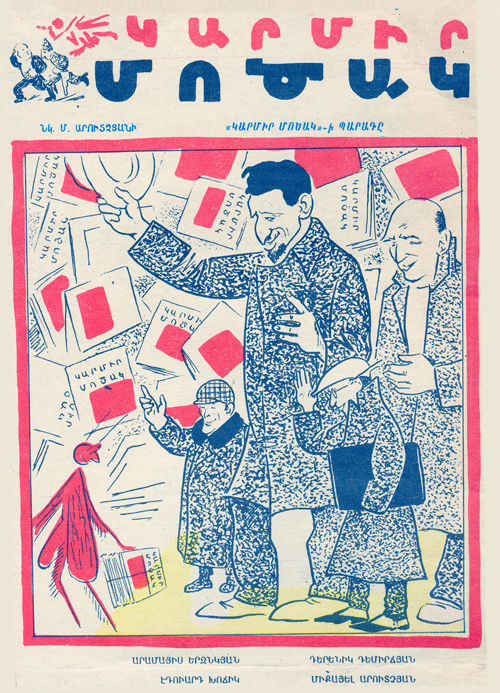

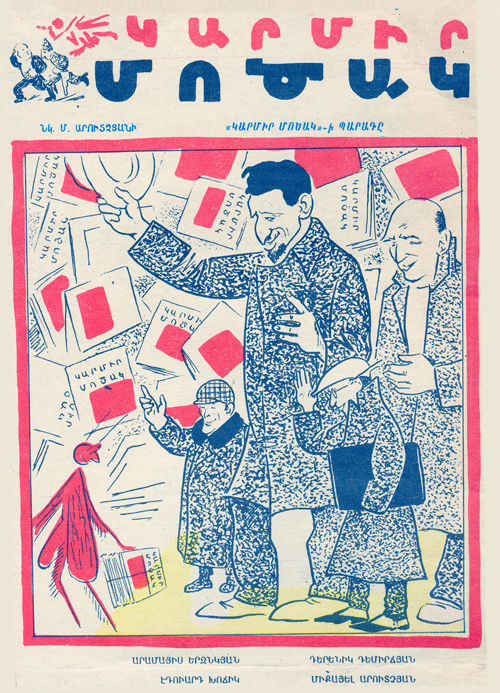

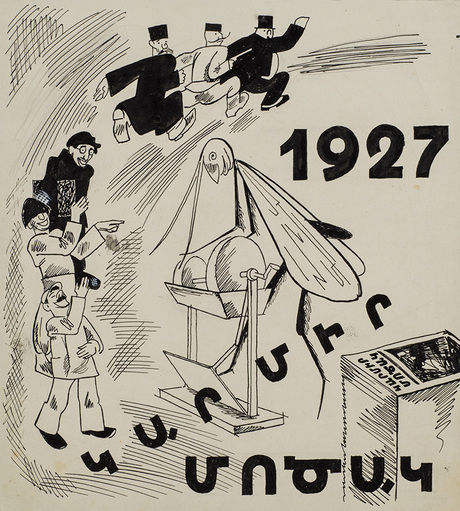

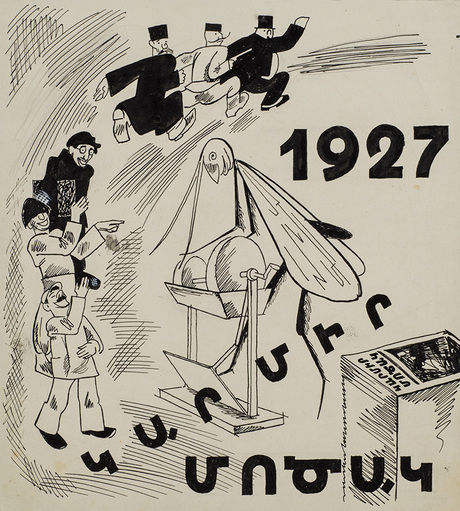

Ruben Arutchyan’s father, Sergey Arutchyan, was for many years the chief illustrator of the Armenian satirical magazine called Vozni,[7] and his uncle, Mikayel Arutchyan, was the illustrator of Karmir Motsak.[8]

Arutchyan says that after Armenia was sovietized, it was divided up and what was left, was left. “Who were we supposed to write against? Against whom were we to draw? The Dashnaks,” he says.

International Humor Competitions

International competitions and festivals were an opportunity for Armenian artists and caricaturists to share their work. “An example is Gabrovo[9] – a famous city of laughter and humor, where biennials have been held since 1972,” Arutchyan says. “I have participated several times and have even received a certificate for my work. It was interesting; you were free there.”

However, there was a nuance: in order to send pictures to international festivals, the editors had to approve the content. “I was not entirely free,” Arutchyan admits. “They were always checking. Eastern Europe was freer; there were many famous Polish and Bulgarian caricaturists. Humor and satire must have freedom. If they do not have freedom, they become meaningless.”

Independence

After the declaration of independence in 1991, the Armenian press seemed to become freer. Many newspapers were established that began publishing caricatures and the caricatures published in the free press of Armenia were more edgy, sometimes even insulting. Arutchyan believes the artist must sometimes censor himself.

“You must not insult. For example, I do not accept Charlie Hebdo. I think they are a little too harsh. Parallel to gaining freedom, self-censorship began to disappear. There was some silence following independence, there were almost no cartoons. What was there to ridicule? People were fighting for independence, and 99% were in favor of independence. We broke away, we were building our country. We had no topics – yet… until the leaders of the country started giving us those topics. They are the ones who give us the topics; we do not invent them,” he explains.

A Caricature Must Have Its Unique Style

Caricaturists of the Soviet period could be recognized by their style, Arutchyan says. “The style of Levon Abrahamyan, one of our cartoonists, is recognizable, as well as those of Harutyun Samuelyan, Sukias Torosyan. I liked to make meaningful, philosophical caricatures, not specific ones, say, like drawing the authorities of the day, criticizing and ridiculing them. Others think differently, and this difference gives birth to the mosaic,” he says, adding that it is important for the artist to have “their own handwriting.”

The Armenian School of Caricature

There have been individual Armenian caricaturists, but not a school of caricature as such according to Arutchyan: “We have had long breaks, from Karmir Motsak until the appearance of Vozni. Our [school of] painting did not have a break – from the Hovnatanyans to Saryan, and we are still painting… There is a school.”

Vozni published many socially oriented cartoons mocking alcoholism, laziness, adultery and other human weaknesses. Did caricatures help solve those issues? Arutchyan doesn’t believe they did: “These were systemic problems. We were concerned only with the consequences and would criticize, but we all knew what the reason was: the country. That is why the more menial issues were left – the problem of garbage, the abuse of small shopkeepers and the pot-bellied capitalists drawn with a bomb in hand. We were not allowed to understand the causes.”

The Honorarium

Newspapers paid five to nine rubles for caricatures, magazines paid 10-15. “When I was a student, cartoons helped me a lot. Add my student stipend to this, and I was a rich student,” Arutchyan says laughing.

When the Karabakh Movement began in the late 1980s, Arutchyan started making posters. “A poster is not far from satire; it is just a different style, more general in terms of performance and more concise,” he explains. “If you draw the poster sharply, it is no less worthy than a cartoon. If you do not have humor, you cannot make a poster.”

He says that in those days, everyone was helping the movement: “The posters were distributed, not sold. They were printed in the Tseka Printing House.[10] It was a big wave of posters. I’m proud to have participated in it.”

* * *

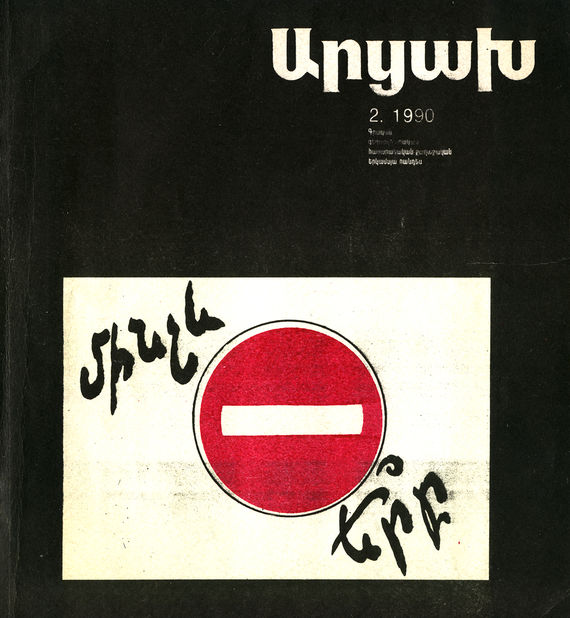

Caricature was an inseparable companion of the newspapers that were being formed under the new freedoms of speech and the press of independent Armenia. While the caricatures and posters of 1988-1990 were mainly directed against the Soviet power, the Center, the political and social content of the caricature gradually appeared in the independent Republic of Armenia.

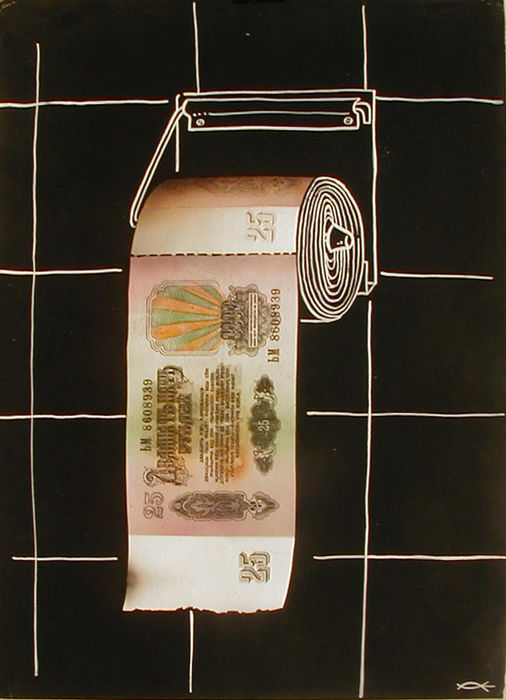

The caricatures published in the Armenian press in 1990-1991 can be conditionally classified as having internal and external directions. The anti-Soviet tendency continued to prevail in the external. At that time, although the collapse of the USSR was already being signalled, it was still a powerful country. The caricatures dealt with occurring events and demonstrated the problems and difficulties, as well as public expectations that existed in society, in a more acute and vivid manner.

The deterioration of social conditions was also apparent in the caricatures. In the USSR, many essential goods could only be acquired by people through ration coupons. In the final period of the collapse, the deficit of goods became one of the main themes for caricatures.

* * *

In February-March 1991, the central government of the Soviet Union initiated a referendum on the formation of a new union. It was called the “Renewed Union,” which would give greater powers to the constituent republics of the Union. However, some Soviet republics, including Armenia, had already begun the process of declaring independence. The Baltic States, Georgia, Moldova and Armenia refused to participate in the union’s referendum. At the same time, however, there was concern that the USSR might toughen its stance on the Soviet republics and use force. Time has shown that this concern was not unfounded.

The caricatures in the Azg newspaper addressed social-political issues. In the beginning of March 1991, Armenian intellectuals met with the leadership of the republic in the Supreme Council of Armenia. The newspaper quotes excerpts from the speeches of the meeting’s participants without any commentary and a few sentences from the speech of the Chairman of the Supreme Council Levon Ter-Petrosyan at the end which read: “It is a difficult process. We want to turn the fake, phony, distorted, twisted world into a real, natural world.” Khoren Abrahamyan, Vardges Petrosyan, Sos Sargsyan, Victor Hambardzumyan, Khachik Stamboltsyan and others can be seen in Sukias Torosyan’s caricature.

It is noteworthy that Khachik Stamboltsyan is depicted in the same way as in the caricature entitled “Who are they?” printed in the 3rd issue of the newspaper (February 23, 1991, No. 3). The artist was Sukias Torosyan, known by the pseudonym Toto. However, at that time, he was known by the pseudonym Toros.

The caricature “Who are they?” has no accompanying text. Famous politicians of that period – Levon Ter-Petrosyan (Chairman of the Supreme Council), Vazgen Manukyan (the first Prime Minister of Armenia), David Vardanyan, Igor Muradyan and Khachik Stamboltsyan – are depicted sitting on children’s wooden horses. The author took the title of the caricature from a very popular folk song of the late 1980s and early 1990s:

“Who are they? Hooray, what daredevils they are,

As Masis is our witness, they are the Armenian heroes.”

With the development of the Internet, the number of caricatures, like that of newspapers, gradually decreased. Some digital media continued to publish caricatures, but not in large numbers and not regularly.

After the final victory of digital media in the 2010s, the only satirical newspaper of that period, Tsets, was published in Armenia for some time, with most of its content consisting of caricatures.

Satirical magazines were also gradually being pushed out after the 1990s. It’s true that Vozni was still being published for some time, but it did not have the popularity of the past. During those years, a number of humorous-satirical newspapers were also published in Armenia, which did not have a long life. Simultaneously, there was already a noticeable decline in the quality of humor, which was alien especially to readers familiar with Soviet satire.

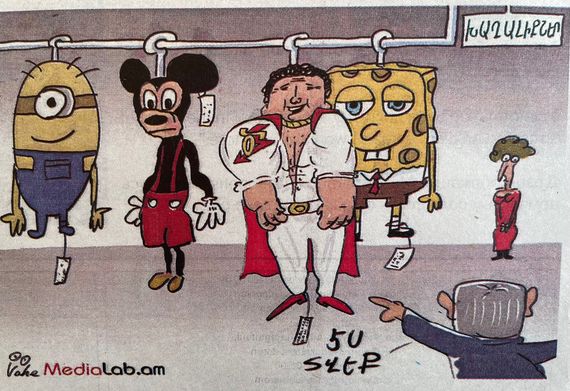

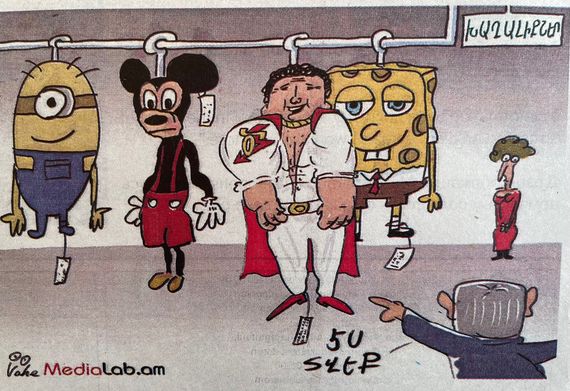

Marianna Grigoryan and illustrator Vahe Nersesyan are the founders of Tsets and the Medialab online project.

Grigoryan thinks that, in the post-Soviet period, almost everything has, in general, become more primitive. “Humor, satire, and feuilleton are among the most difficult genres. On the other hand, if we take television, can we compare it with the seriousness and intellectuality of Soviet-era programs? I think there is a big gap in the field of humor now, and there is a lack of quality humor,” she says.

Nersesyan believes that humor, of course, should be free, but to understand the humor of the Soviet period, a certain level of intelligence is necessary: “Nothing is required now; in this respect, the unprepared spectator will nevertheless perceive it!”

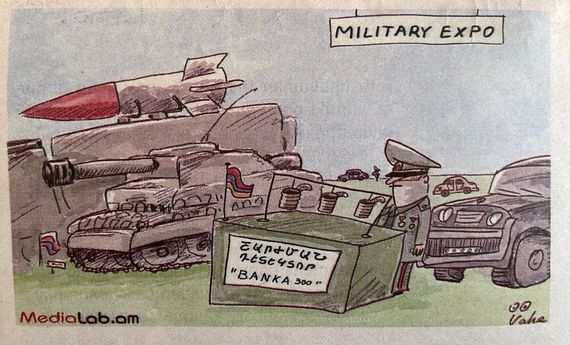

The Armenian Charlie Hebdo

Medialab has a rich selection of political caricatures – ruling and opposition figures, MPs, clerics, public figures – almost all of them appear in the Caricatures section of the website. “If the caricature is not sharp, is not painful, it will not have an effect and will not contribute to change. When we started, a politician wrote on Facebook: ‘The only thing missing was Charlie Hebdo, and now we have that too,’” says Grigoryan. She explains their success by combining journalism and political caricature, and also notes that they stay within their limits and do not reflect on everything with humor.

On the USSR and Independence

Marianna Grigoryan believes the situation changed in the 1990s when newspapers began having a certain political orientation or supporting a particular political figure and this new reality impacted caricatures. “In addition, the caricatures of the 1990s were not editorial cartoons, but were drawn for the articles,” Grigoryan says. “Later, I worked for the Armenianweek and Armenianow newspapers, where we had American and British editors who appreciated the genre of caricature, and we published caricatures once a week.”

Vahe Nersesyan says that his work is greatly influenced by Georgi Yaralyan, whose style was not necessarily political; they were about everyday life, about couples, although they were very Armenian. As for the limits of permissibility, Nersesyan says there are two dimensions.

The first depends on the country where you live. “For example, in France, Charlie Hebdo can write insults for which, in our reality, we could be stabbed. In France, it is published, and the Frenchman does not jump up and exclaim ‘What is this?’ when he reads it. This is not acceptable here; you cannot publish such a caricature. There are other barriers: family, sex life. There are places where the caricaturist has no right to set foot. I mean, you can, but there will be consequences, and you will not be accepted,” Nersesyan says.

The second dimension is the personal. “Unlike an article, the caricature is subjective and depends on the artist’s personal point of view, position and political preferences, where the artist’s personal attitude toward the subject of the drawing plays a big role,” Nersesyan explains. “For example, I treat some politicians more leniently; I do not say I like or accept them, no. There are characters I cannot stand. This is apparent in my caricatures, maybe it’s unfair…”

* * *

No matter how attractive or stinging the caricature may be, nevertheless, a question arises as to how much it contributes to the solution of real and potential problems. Maybe by addressing the issue with humor, we reduce its importance. Grigoryan and Nersesyan believe quite the opposite: the issue receives more attention through caricature. Maybe, however, not everything is so unequivocal in the endless world of media.

—————————–

[1] Literaturnaya Gazeta is a well-known literary weekly, published since 1929. The founder was writer Maxim Gorky. The newspaper’s header featured portraits of Alexander Pushkin and Maxim Gorky. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the image of Gorky was removed from the header, which was later reintroduced in 2004. The newspaper is still published today.

[2] A famous Soviet satirical magazine, published since 1922. The magazine has published works by Mikhail Zoshchenko, Ilya Ilf and Yevgeny Petrov, Alexander Mayakovsky and other famous writers during different times. In 1933, the People’s Committee of the Ministry of Internal Affairs “discovers a counter-revolutionary group” in the editorial staff of Krokodil and arrests several people.

[3] The informal name of the newspaper Literaturnaya Gazeta.

[4] Mikhail Zhvanetsky (1934-2020), famous Soviet writer, satirist.

[5] Colitis is an inflammatory disease of the bowels. It has many varieties.

[6] There was a severe shortage of basic necessities in the Soviet Union, with shopkeepers often selling the goods that were in demand at higher prices. These transactions were “under the table.” For example, “I bought this shoe under the table” meant that the shoe was not available in the store; it was not displayed, but it was bought, of course, at a higher price.

[7] Vozni was an Armenian satirical magazine, published since 1954. The editors-in-chief were Hrachya Kochar, Grigor Ter-Grigoryan and Aramayis Sahakyan. Ler Kamsar, Ashot Palanjyan, Derenik Demirchyan, Suren Vahuni, Valentin Potpomogov, Ara Bekaryan and others were correspondents of the magazine.

[8] Karmir Motzak was an Armenian satirical biweekly, published in 1926-1927. The editors were Aramayis Yerznkyan and Eduard Khochik (Khochikyan).

[9] Gabrovo is in Bulgaria. It is considered to be Bulgaria’s city of humor. The people of Gabrovo not only created humorous short stories on various topics, but also themselves became the heroes of these anecdotes. During the Soviet years, anecdotes about the people of Gabrovo were also translated into Armenian.

[10] Publishing house of the Central Committee (CC) of the Communist Party of Armenia. After independence, it was renamed to Tigran Mets Printing House. In the colloquial language, it was called Tseka Printing House, from the Russian pronunciation of “Central Committee.”