Listen to the article.

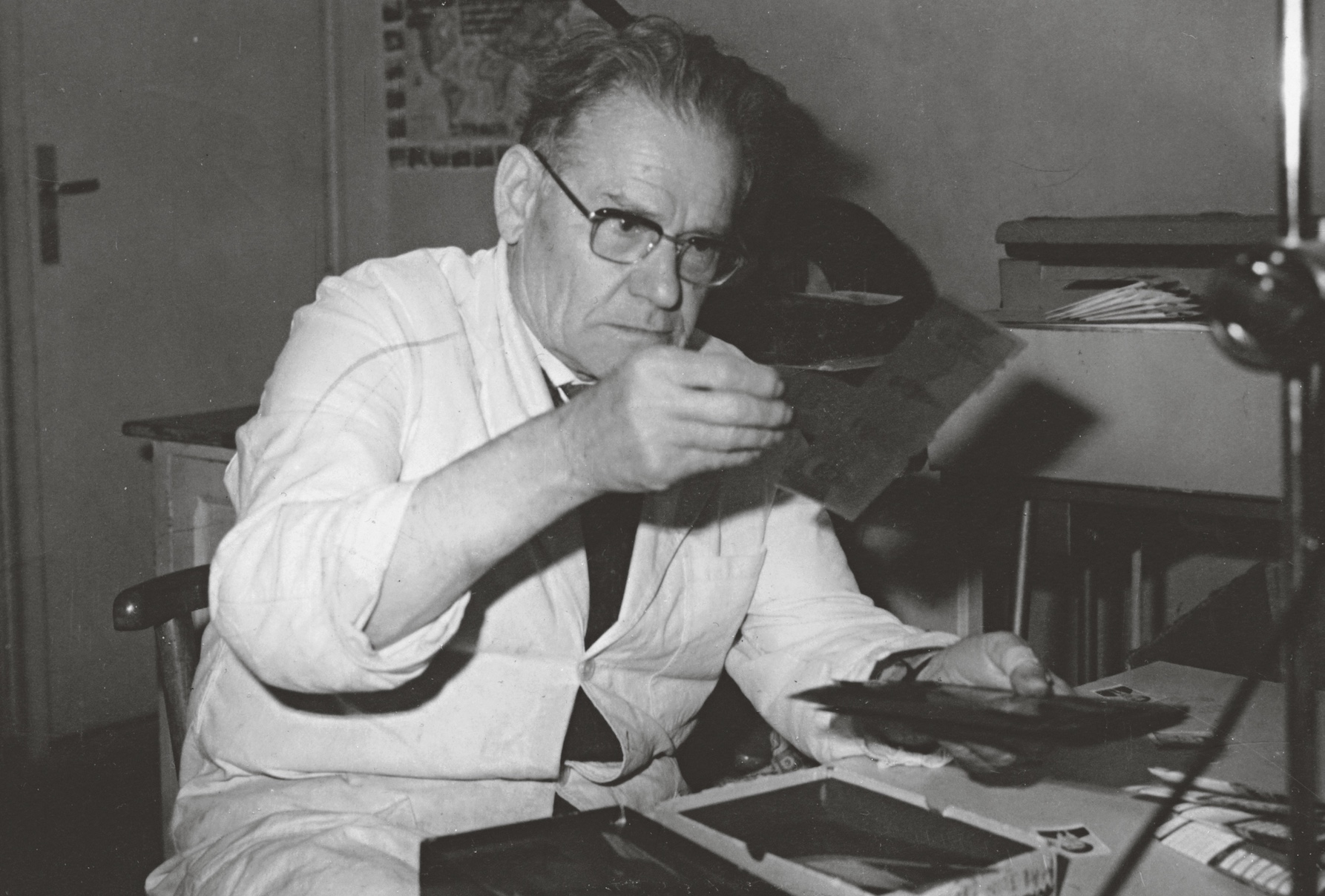

The archives of Studio Rex bear witness to the massive waves of migration that transformed the port city of Marseille—and, by extension, the face of Europe—throughout the mid-to-late 20th century. Founded by Armenian Genocide survivor Assadour Keussayan, today the photo studio’s legacy endures through Jean-Marie Donat, the archive’s last custodian and living voice.

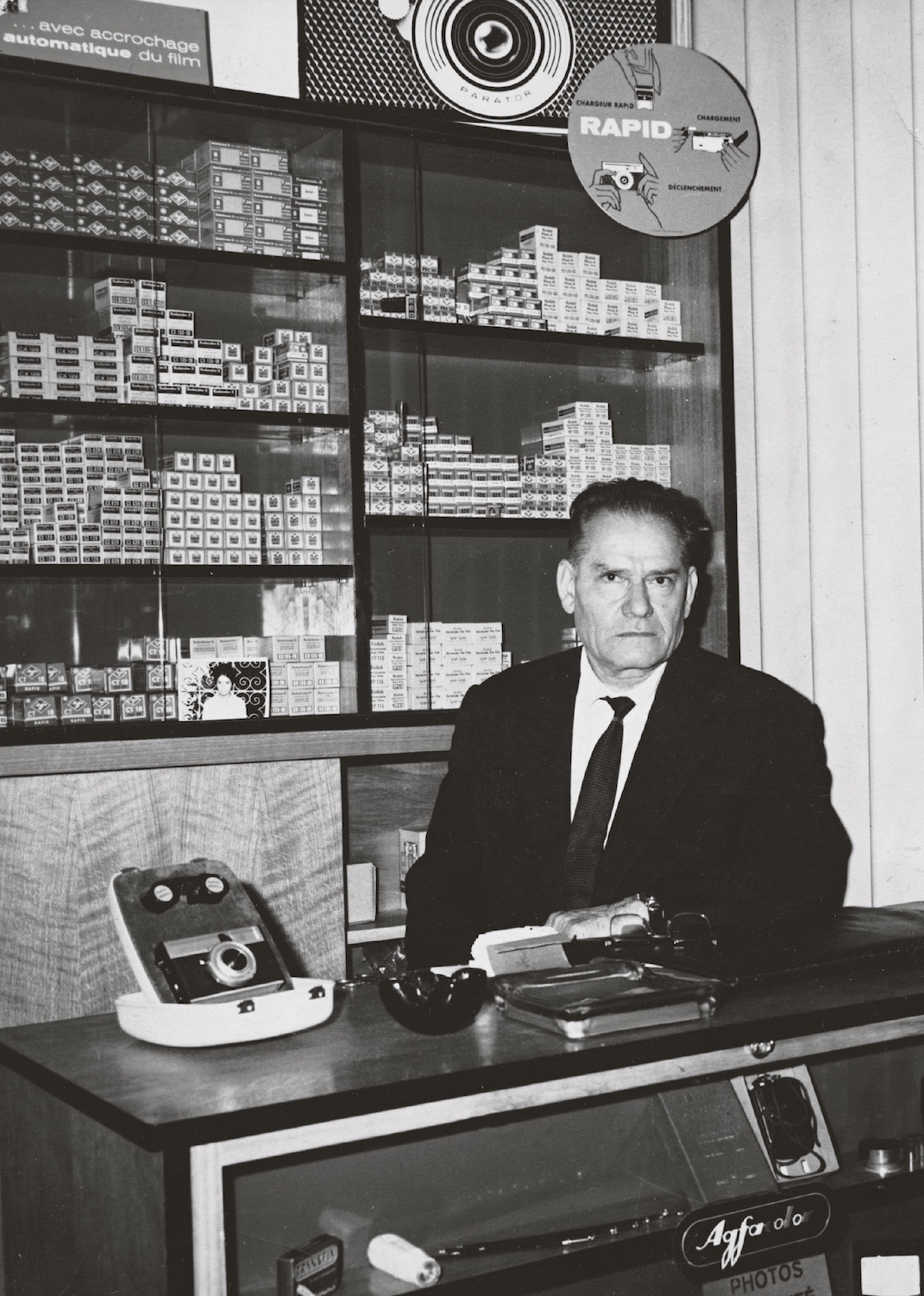

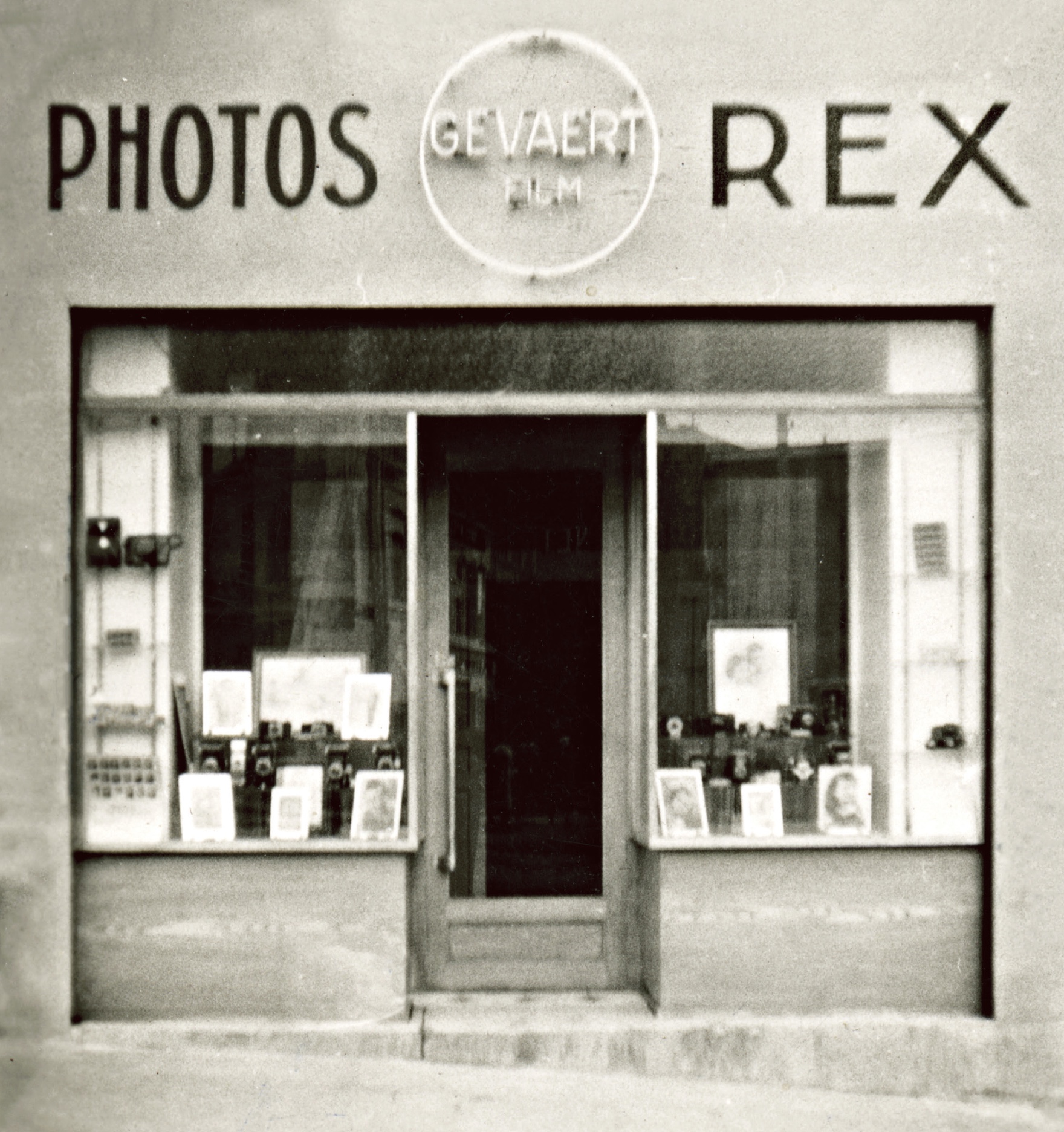

When Assadour Keussayan opened a modest photo studio in Marseille’s Belsunce neighborhood in the 1930s, he was making a pragmatic business decision. “Money is money. The prices were written on the door,” says Jean-Marie Donat in an interview with EVN Report. A survivor of the Armenian Genocide, Assadour arrived with little more than the clothes on his back. His initial affinity to photography could be traced to the Ottoman Empire, which had embraced the medium early and was home to many pioneering studios by the mid-19th century.

But Assadour was far more than a photographer. “He was an Armenian activist,” says Donat, “regularly attending meetings and taking part in Armenian clubs and associations in Belsunce, some of which still exist today.” Donat, who now owns the Studio Rex archive, has brought its legacy to new life through a book, Ne M’oublie Pas (with texts by Souâd Belhaddad), and a major exhibition simply entitled, Studio Rex. The exhibition premiered at Les Rencontres d’Arles, one of the world’s most prestigious photography festivals, before traveling to the historic C/O Berlin photography museum in 2024. A special showing was also held for the Belsunce community.

“It was very touching,” Donat recalls. “People really loved it.”

Assadour saw himself first and foremost as a craftsman, no different from the cobblers or jewelers who worked alongside him in Belsunce. What mattered most was offering good service. “He was proud that people returned to him, satisfied with the work he was doing,” Donat explains. Yet the medium he worked in—photography—was on its way to becoming one of the defining tools of modern life. As photography became more accessible, weaving into the fabric of daily life, media culture, and the bureaucracy, his studio quietly became a fixture of this transformation.

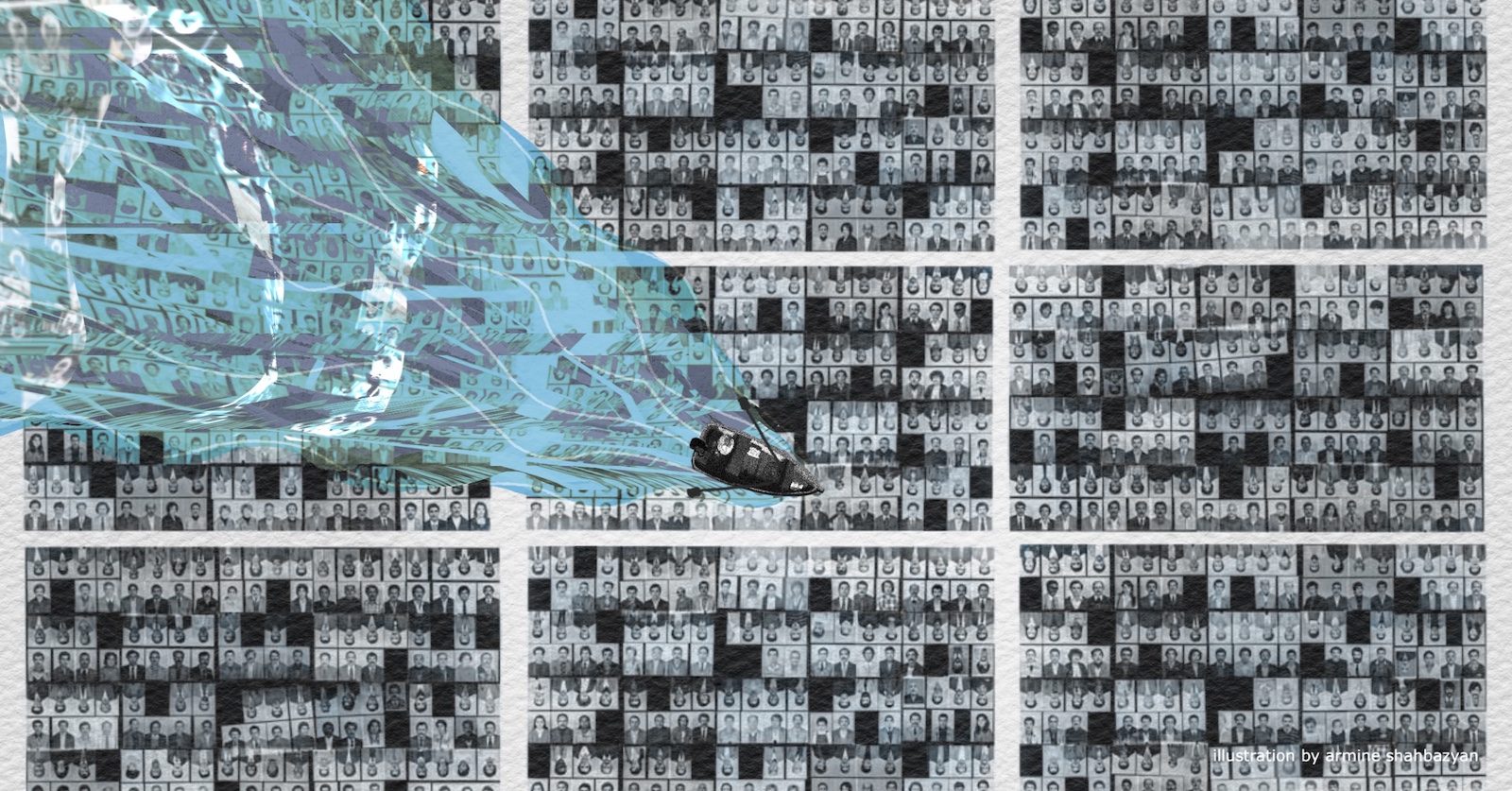

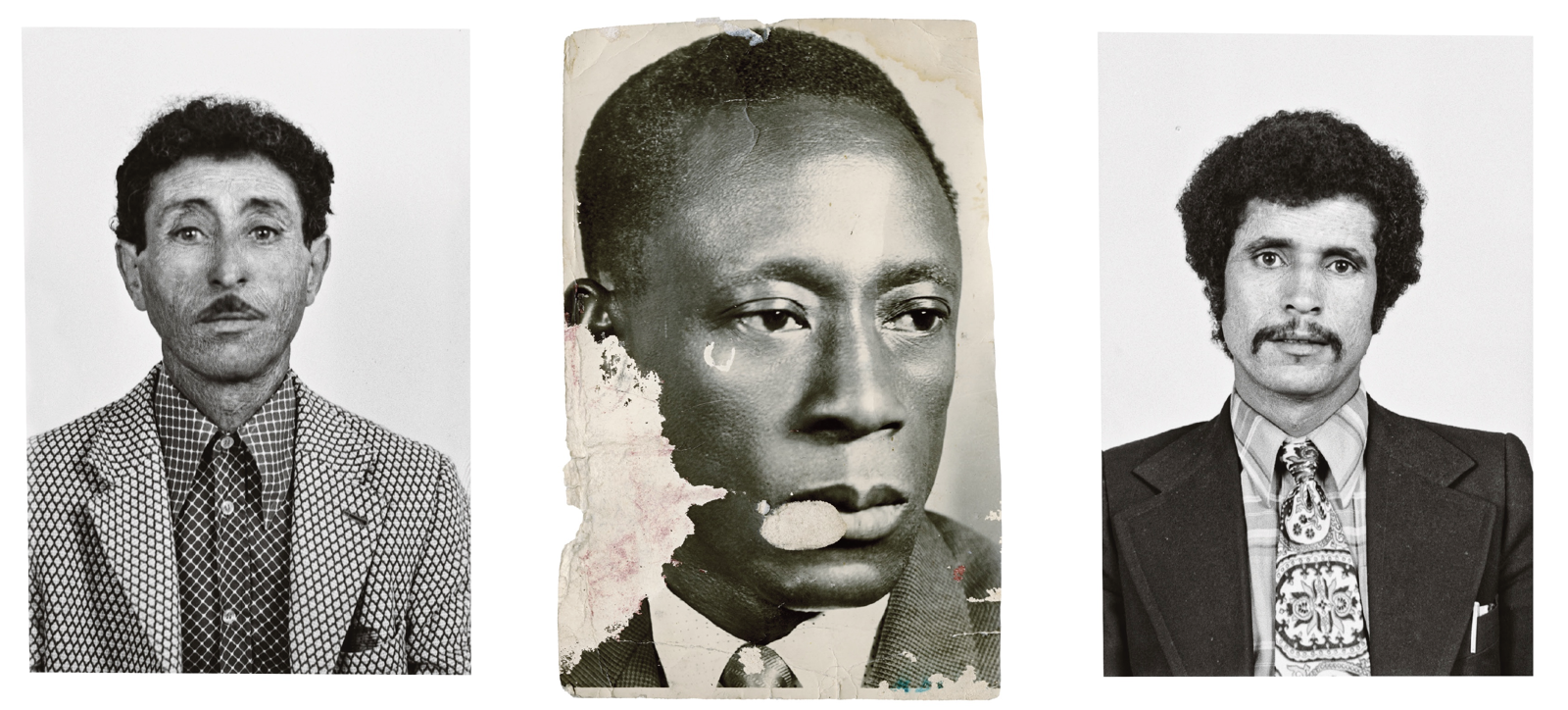

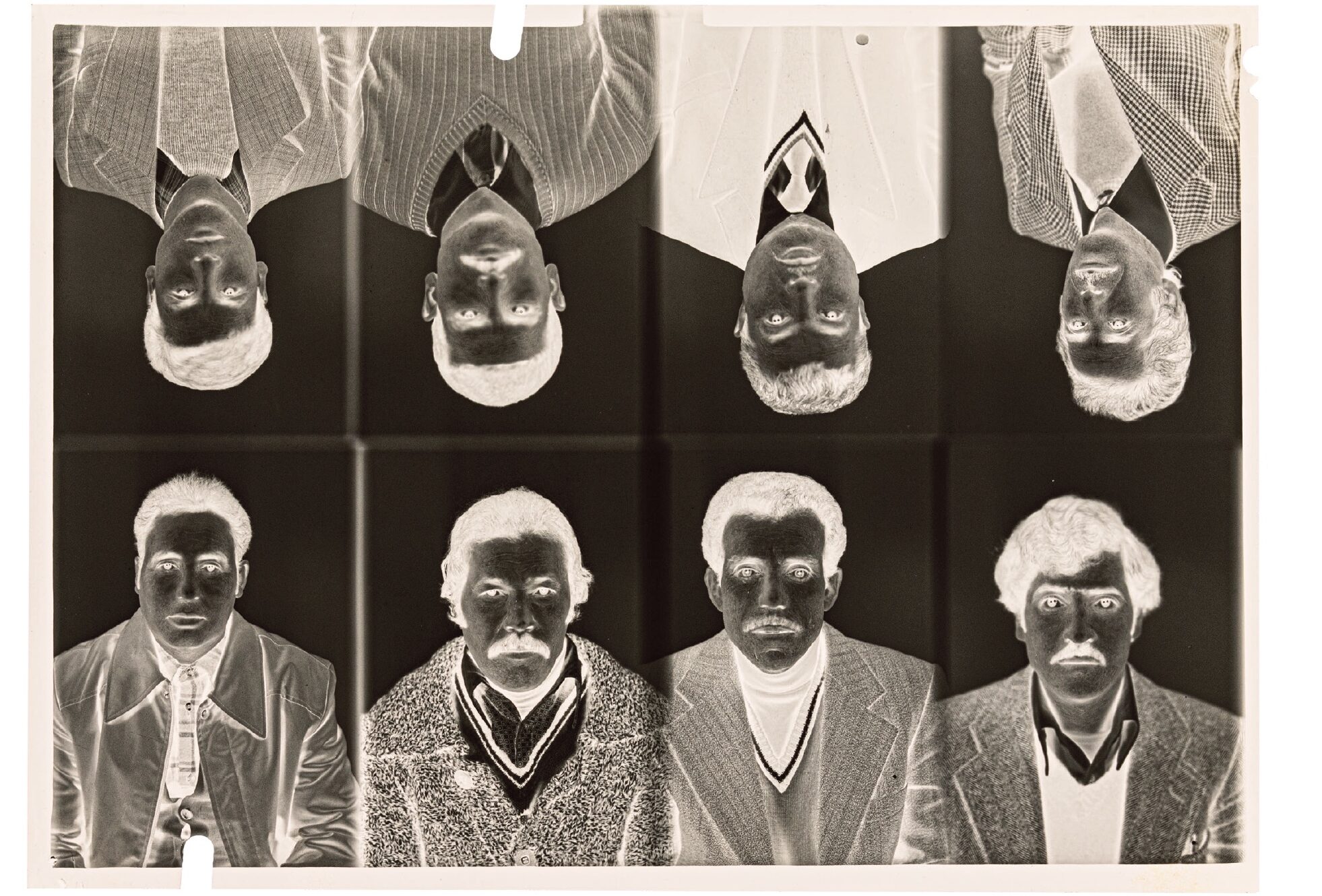

Perhaps without even realizing it, the Keusseyans, by opening a small, cramped photo studio nestled perfectly in the predominantly migrant neighborhood between the Vieux Port and the St. Charles train station became quiet witnesses to thousands of lives. The portraits, composed in the neutral, austere style typical of studio and administrative photography, have taken on new resonance today. In a Europe still wrestling with questions of identity, migration, and belonging, these images carry a renewed poignancy and power.

Studio Rex, with its wide array of services, from passport and wedding photos, to studio portraits to send back home, and reproductions of personal family photos, single handedly documented the lives of a population whose legacy still reverberates across Europe. At a time when Marseille was emerging as the epicenter in the Euro-Mediterranean merchant network, it was migrant entrepreneurs like Assadour who kept the engine running.

“During the Algerian War [1954–1962], there were waves of immigration from Algeria, the Comoros, sub-Saharan Africa, and the French departments of West Africa,” Donat explains. “Most of them settled in Belsunce, and they became the main clientele of the studio.” In 1962 alone, more than half a million newcomers arrived in Marseille, many fleeing the turbulence of decolonization. Their arrival sparked tension, as France struggled to absorb and support the influx. That strain reshaped the city’s social fabric, adding layers of complexity to its evolving identity. Even today, Marseille remains a city rife with cultural contradictions, a cacophony of struggles and coexistence.

In an excerpt by Souâd Belhaddad in Ne m’oublie Pas [translated from French], she writes of the significance of Marseille’s ever-present role in Europe’s cultural landscape: “Through successive waves, the events of economic and political history have scattered a rosary of migrants, refugees, activists, survivors, repatriates… Italians, Armenians, Eastern European exiles, North African Arabs, repatriates and pieds-noirs, Comorians… Marseille represents the plurality of political and social tragedies, transformed into a port-city of hope. Arriving, departing, staying, waiting, settling, leaving again, passing through… the city, embracing the Mediterranean and opening pathways to five continents, responds to every dream and every promise.”

Studio Rex became a symbolic bridge between waves of migrants arriving in Europe and the homes they had left behind. It served as a small but vital hub, helping newcomers finalize immigration documents and navigate their new lives. More than that, it stood as a quiet testament to a genocide survivor who welcomed everyone equally, even as anti-immigrant sentiment grew in France with the rise of the far-right Front National party in the 1970s. Even after the studio ceased operations, Donat recalls that its doors remained open, continuing to serve as a gathering place for the neighborhood. In the early 2000s, Assadour’s son, Gregoire Keussayan, could often be found sitting outside, playing cards and drinking coffee.

Spanning almost seven decades, the photo studio was, by default, a witness to the history unfolding around it. But of course, the photos were never meant to hang on a gallery wall. “[The Studio] was very pragmatic. They were photographers, they were artisans. They took their photos without asking themselves any questions,” says Donat.

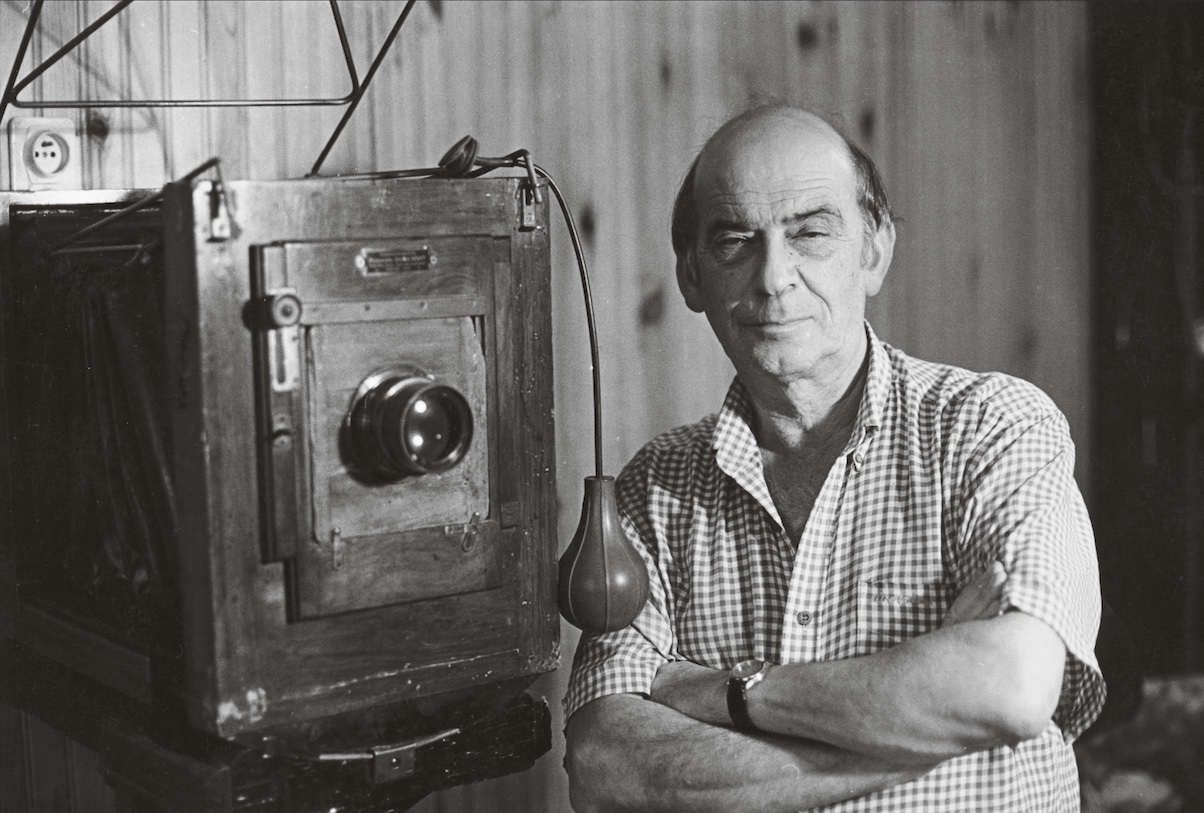

Similar to Assadour’s blind intuition at the time, it was also a stroke of happenstance which lead Donat to acquire the archives of Studio Rex. Originally approached by a photographer with a proposition to buy some negatives, he dismissed the idea at first but decided to give the follow-up email a chance. After skimming through the attached PDF-file, Donat was drawn by the array of striking, anonymous faces from all over the world. By then, Assadour’s son Gregoire, had long since taken over the studio and he needed to make sure their life’s work would not disappear into the abyss.

Slowly but steadily, Donat started receiving boxes of negatives in Paris and eventually was able to get a hold of Gregoire himself—not the easiest person to find. For about a decade, Donat and Gregoire’s peculiar friendship and comradery was bound by the stories in those archives and their newfound value. According to Donat, Gregoire at first would pack boxes on the train in Marseille St. Charles station which Donat would pick up off the train in Paris.

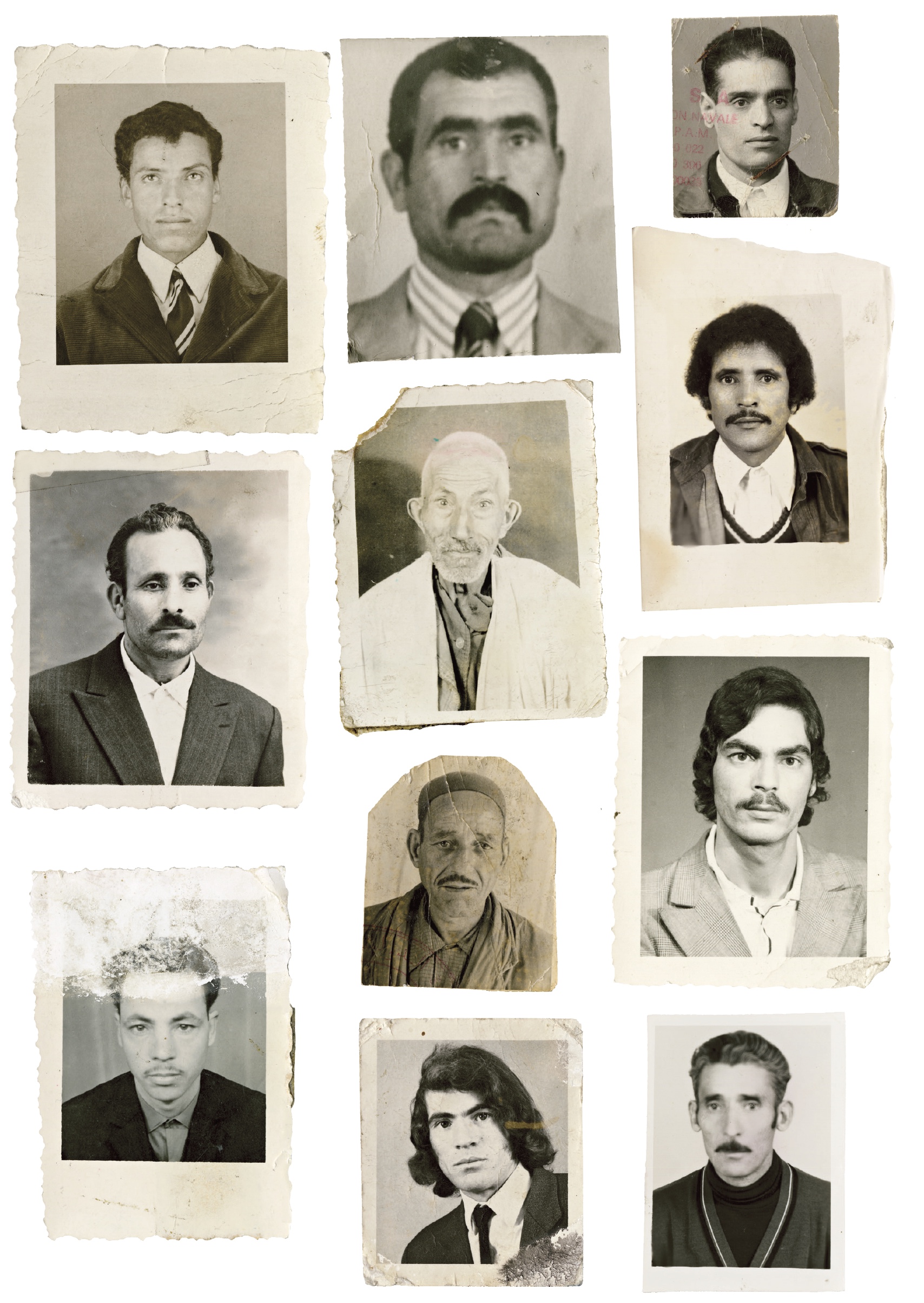

Overwhelmed by the sheer size of the archive, Donat finally went down to Marseille himself to finish the job. One day, Gregoire handed him a suitcase containing reproductions of wallet photos—small family photos from home that had accompanied the customers on their journey to France. Donat had now found the missing link, he now had a story.

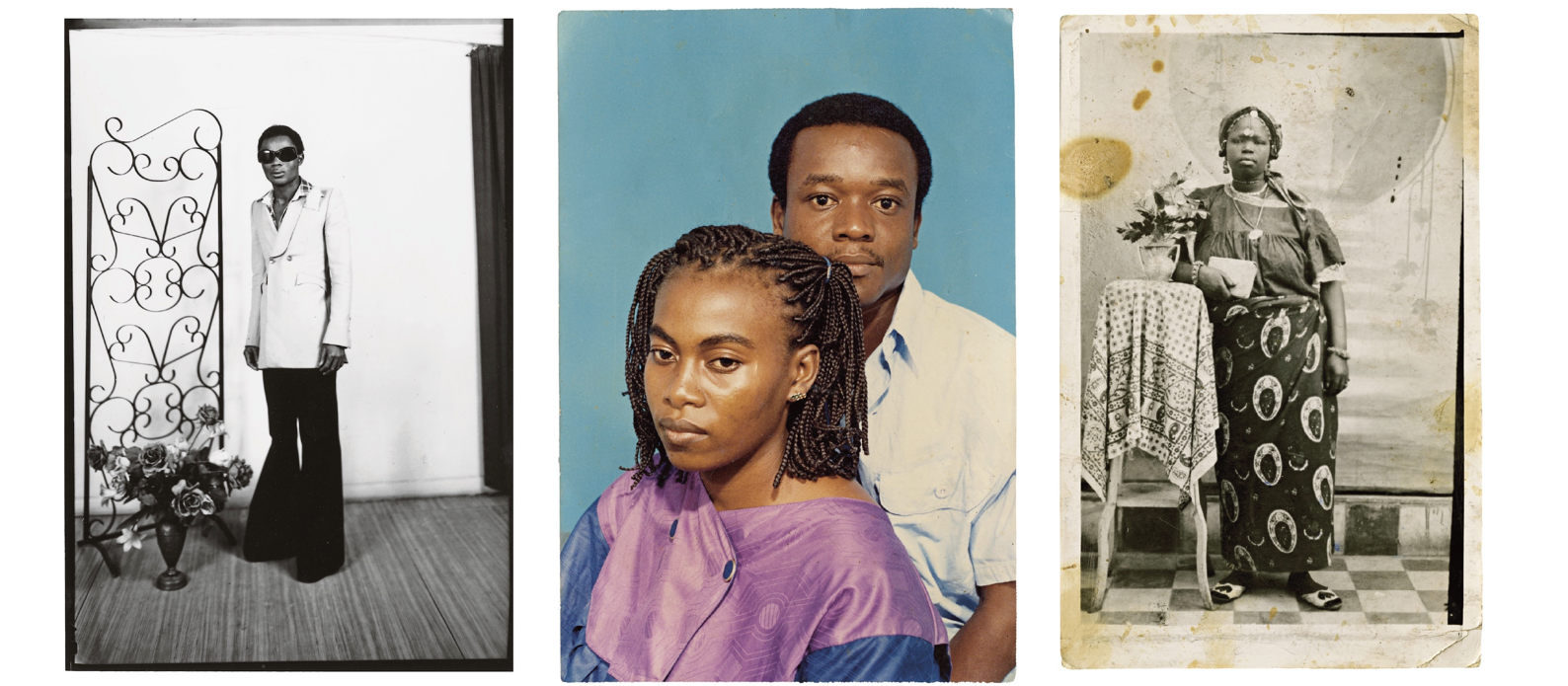

The archive turned out to be a 360 degree blueprint of the migrant experience: the wallet photos told of their homelands, administrative portraits became a testament to their new immigration status, while the studio images, with their idyllic backgrounds and finest attire, told of the illusive “European Dream” his clients wanted to convince their families of.

“Gregoire told me that Assadour had a lot of compassion for these people because he had made the same trip,” Donat recalls. “And he hadn’t forgotten that.” Assadour fled Turkey as a child during the Armenian Genocide and “followed the caravans in the desert to arrive in Lebanon. There, he was taken to a French orphanage.” Eventually, he arrived in Marseille around his teenage years and began working in the sugar refineries until he began to work as a photographic apprentice.

“So he works, [Gregoire] tells me, for a great Marseillais photographer. The only great Marseillais photographer I know is Nadar’s son,” says Donat. Nadar, pseudonym for Gaspard-Félix Tournachon, was one of the most important French studio photographers at the turn of the 20th century. Donat speculates that Assadour could have assisted Paul Nadar [Nadar’s son], which would have meant that Assadour was trained by one of the best in the industry.

Donat says that as the 1930s came around, Assadour opened the studio in Belsunce. “And until the end of his life, he worked as a photographer in this studio. At the beginning, there was not yet a lot of immigration in Belsunce, which was still pretty bourgeois,” says Donat. As history evolved, he started photographing colonial troops, Moroccan rubber tappers, Senegalese snipers and those in the surrounding neighborhood; at the time, the negatives were still on glass plates. “From this archive, there is nothing left,” says Donat, because Assadour would destroy the plates to avoid the tax inspectors and to make space in the small studio.

After shutting down during World War II, Assadour reopened the studio’s doors with the help of his Cypriot wife Varsenik, his son Gregoire and his daughter Germaine as the war came to an end and the glass-plate negatives were out of style. Gregoire would assist his father in taking the photos, developing and making the prints, while Germaine, who passed away quite young, would take care of the retouching and editing.

By the 1960s, the Armenians had been in Marseille for over 30 years and had taken their place in French society. Studio Rex, alongside their business-as-usual photos, began photographing weddings of affluent Armenian families, always advertising the classic wedding-photography in the window displays. “One day, an Algerian man came in and asked Gregoire to take a beautiful Armenian wedding photo and to insert his and his fiancée’s faces into the photo…The client wanted to be in the photo and send it to his family. He wanted to have a beautiful wedding photo, even though he was in France and his wife was in Algeria,” says Donat.

“Assadour, according to his son, was very honest,” Donat goes on. “For many clients, including Senegalese riflemen, the studio functioned as an informal bank. They entrusted their money to Assadour, who meticulously recorded their finances in a small notebook—a service he offered out of profound respect.”

Donat shares richer stories from the studio: Iranian women who would transform themselves at nearby boutiques before posing draped in gold accessories. The studio provided elaborate props, elegant clothing, and scenic backgrounds to project an image of prosperity. “Some clients from sub-Saharan Africa would showcase currency bills in their portraits,” Donat notes. “Some even affixed bills to their foreheads to demonstrate their financial success.”

These anonymous photographs make space for narratives that are both true but also imagined, presenting questions about all the forgotten stories of migrant families: Did they ever reunite? Do their surviving relatives still have a copy of these images tucked away somewhere? What was the last thing they said to their families before leaving? Who did they leave behind? Were they happy in Europe? What was their journey like? What did they go on to do in Europe, and where? Did the immigration documents go through? Who do the photos belong to—the collector, photographer or subject, or to history’s collective memory?

“I can show very personal things, historical things, things with a sociological relationship. A photographer has a style, he has a way of working. He takes his photos. I’m a bit like a chameleon. I dress up with the archive on which I work…My work is the book or the exhibition. And my equipment, my camera, is the photos of amateurs,” Donat says about his approach. His artistic practice is centered around photography collection and iconography, alongside editing and publishing with several major exhibitions in his repertoire.

The book and exhibition present the archive much as Donat received it—stripped of names, dates and context. Rather than selecting images based on artistic merit, Donat deliberately preserved their vernacular quality, honoring their origins as practical, everyday photography. “Today, it’s up to us to project onto them what we imagine, based on our own journeys, perspectives and histories. Photography here leaves us no other choice,” writes Belhaddad in Ne M’oublie Pas.

With the backing of editorial director Julien Friedman and Les Rencontres d’Arles director Christoph Wiesner, the legacy of Studio Rex made its way to the prestigious Arles festival. The exhibition featured a selection drawn from 700 wallet-sized photos, 10,000 passport negatives, and more than 100 studio portraits taken between 1966 and 1985. Tragically, Grégoire passed away just one month before the opening. The exhibition debut carried profound emotional weight for Donat, now the unexpected final guardian of this visual heritage. During their last meeting before the vernissage, Donat asked, “Don’t you think your father would be proud of the work you did?” Gregoire responded with characteristic humility: “Yes, I do.”

Photos courtesy of Jean-Marie Donat.

Also see

Mariam Shahinian: Out of the Shadows

With the recent discovery of Turkey's first female professional studio photographer Mariam Shahinian, a group of women are inspired to work together to try to decipher this page of her story left in the shadows.

Read moreArchive Fever: Vanadzor’s Bucolic Past in Hamo Kharatyan’s Photographs

How a tightly rolled bundle of negatives taken by Hamo Kharatyan in the 1930s slowly began to reveal astonishing, quite unfamiliar aspects of Vanadzor's life that were already on the verge of disappearing.

Read moreStudio Belle: Armenian Photo Studios and the Changing Standards of Female Beauty

The first Armenian-owned photo studios in Constantinople and Tbilisi at the end of the 1850s not only immortalized people’s lives, they were an effective shortcut to modernity and a powerful symbol of cultural emancipation.

Read moreBehind the Magic: Rudolf Vatinyan’s On-Set Photographs From “Khatabala”

When cinematographer Rudolf Vatinyan passed away from COVID-related complications in 2020, people eulogized about an exacting professional who had filmed a number of iconic films. No one remembered, however, that Vatinyan had a parallel creative passion.

Read more