Whenever civil unrest emerged in the Roman Empire or the emperor sought to pacify subjects amid internal political turmoil, two effective things were employed: bread and circuses.

In today’s world, there is no shortage of circuses but bread can be scarce. The Russo-Ukrainian war resurrected the role of grain supplies as a political instrument, exemplified by the Grain Deal, aimed at ensuring a steady supply of wheat in the face of disruptions

For Armenia, the production and import of wheat are critical security issues. As a landlocked country, Armenia has limited external transport links, and in terms of stability, the world — and, in particular, our region — resembles a powder keg.

According to the Law on Ensuring Food Security, the Armenian state is responsible to guarantee food security. But what measures are being taken to ensure Armenia’s food security, particularly in terms of increasing wheat self-sufficiency and safeguarding uninterrupted wheat imports?

The issue of “applying a temporary ban on the export of a number of goods from Armenia to countries that are not members of the Eurasian Economic Union” was discussed during the Government session of November 9, 2023.

Yerevan decided to temporarily prohibit the export of certain agricultural products, including wheat, meslin, barley, corn, buckwheat, sunflower seeds, and sunflower oil, for a period of six months.

The decision is based on ensuring Armenia’s food security and stabilizing its economy. The domestic production of these products does not meet the demand of Armenia’s market. According to the Ministry of Economy, Armenia is not self-sufficient in wheat production. Official data from 2021 shows that the wheat production index of total consumption was 26.4%.

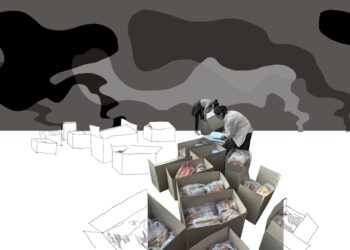

Domestic wheat and meslin production in 2022 was 138.6 thousand tons, while imports accounted for 364.6 thousand tons. Total consumption reached 503.2 thousand tons.

It is worth noting that Armenia imports 99.9% of its wheat from the Russian Federation.

“Our main supplier country is not reliable in terms of sustainability. We buy grain almost entirely from Russia, whose policy is obvious; political issues are at the core of its economy. Among other geopolitical issues, given the current condition of Armenian-Russian relations, Russia may one day declare that it can’t sell as much grain. What are we going to do?” asks Samvel Avetisyan, a professor in Economics and the Deputy Minister of Agriculture from 2002 to 2011. He underscores the importance of ensuring, at a minimum, the fulfillment of the country’s basic requirements through domestic production.

According to Avetisyan, wheat cultivation is currently not profitable for Armenian farmers due to the significantly cheaper wheat imported from Russia. Furthermore, the government’s policy is primarily oriented towards importing rather than striving for self-sufficiency. Although Armenia, as a member of the Eurasian Economic Union, can still import wheat from Russia, this alone does not provide a comprehensive solution to the problem.

Arman Khojoyan, Deputy Minister of Economy, acknowledges that the selling price of wheat in Armenia is relatively low; making it uncompetitive with wheat imported from Russia. However, the issue remains unresolved.

“It is a fundamental question that has persisted throughout time: should we aim for self-sufficiency in the production of crops that are not very profitable? In the case of wheat, for example, the size of the plot plays a significant role in reducing expenses and harvest losses during cultivation,” explains the deputy minister.

In 2022, the government launched a program aimed at increasing winter wheat acreage through the use of uncultivated land, as well as providing government support to farmers. For each hectare of cultivation, the government provides compensation of 70,000 AMD and 12,000 AMD for costs, if wheat cultivation is carried out using certified seed.

According to Khojoyan, the areas sown have increased as a result of the new program, but the question persists. “Maybe it would be more cost-effective to build the infrastructure, such as laying water pipes, utilizing water-saving technologies, and expanding irrigated areas, instead of spending a certain amount of money on expanding wheat sowing areas,” Khojoyan says. “This approach would encourage efficient cultivation and enable the production of crops that are better suited to Armenia’s climate.”

Armenia cultivated 69–70,000 hectares of durum wheat in 2023, which is an increase of 15,000 hectares compared to last year. The Deputy Minister of Economy estimates that the wheat harvest for 2023 will yield 200,000 tons.

“Last year, we harvested roughly 140,000 tons of wheat, but our typical annual consumption is around 385,000 tons,” he explains. “Thus if we produce 200,000 tons, then we will need to import the remaining 180,000–200,000 tons of grain.”

Private organizations import wheat from countries with the lowest logistical and procurement costs in order to receive a less expensive commodity. Each country in the Eurasian Economic Union, including Armenia, determines its own list of essential commodities and the required quantities. All member countries then agree on a general quantity and decide which country will not impose export restrictions. In other words, Armenia’s membership in the EAEU serves as a safety measure for food security, particularly in terms of wheat imports. However, it is possible that this safety measure may not work down the line due to political issues.

Therefore, Armenia requires a new, more realistic food security policy that takes into account geopolitical risks to the extent possible.

The 2023-26 Food Security Strategy and the Government’s decree of June 29, 2023, titled “On Approving the Strategy for the Development of the Food Security System and the Action Plan for 2023-2026”, are not feasible because they fail to accurately reflect the current economic situation. They lack the painful reality that Artsakh is no longer Armenian.

Apart from the unprecedented political and humanitarian crisis, the loss of Artsakh dealt a significant blow to Armenia’s food security, particularly in terms of wheat self-sufficiency.

Official figures indicate that in 2019, Armenia imported 40-50 thousand tons of grain and legumes from Artsakh. However, since the 2020 war, wheat imports from Artsakh have ceased.

Although there is no shortage of strategies, Samvel Avetisyan believes that creating a new food security strategy is necessary but not enough. The problem lies in how the government will implement the strategy. Ultimately, there is a lack of clarity on the most effective approach to meet the population’s demands: should it rely solely on domestic production or include imports? In other words, there hasn’t been a thorough analysis to determine the extent to which local production is justified.

“For instance, in Shirak region, people are unwilling to cultivate or sell the grain they grow because the price is so low that it does not cover their costs,” Avetisyan explains. “Yes, we have never been self-sufficient in wheat and grain, but what should a farmer grow if they don’t cultivate wheat?”

The government has yet devised a clear system to incentivize farmers to engage in grain cultivation. Specifically, 60% of Shirak region’s arable land is suitable for grain production.

“What should the farmer use those areas for? What should they occupy themselves with, if the costs, including state subsidies, are not compensated for?” asks the economist.

There are certain crops and foodstuffs that cannot be completely self-sufficient, and it is also not profitable to attempt to do so. However, while the problem of self-sufficiency can be solved by importing other crops, the government should make every effort to increase self-sufficiency for wheat in the face of political and economic challenges.

Currently, procurers pay farmers 65-70 AMD per kilogram of wheat. This price is justified by the fact that wheat from Russia to Armenia costs importers 65 AMD. As a result of the fluctuation in the dram-ruble exchange rate, bread producers find it profitable to import wheat from Russia.

However, there is still no clear answer to the question of what should be done to support our farmers and agriculture.

“Last year, farmers increased arable land, but they are not planning to plant wheat this year. In Shirak and Gegharkunik regions, where wheat cultivation is the primary focus, there is no alternative,” Avetisyan says. “However, in Shirak, a successful rotation system was established. After planting potatoes and fertilizing the soil, they planted wheat or barley on the same plot of land the following year and achieved good results.”

Despite this, the Deputy Minister of Economy is confident that Armenia has not seen such significant implementation of agricultural development initiatives in the past ten years. Since food and harvesting losses account for a significant portion of the total, the government is prioritizing the purchase of agricultural machinery and minimizing losses during harvesting.

“It is estimated that a third of the food produced globally is lost, which is intolerable considering the 800 million undernourished people in the world today,” says Khojoyan.

According to the deputy minister, food loss in developing and undeveloped countries primarily occurs at the harvest and post-harvest stages, while in industrialized countries it takes the form of wasted final food products. The government believes that a more effective use of its resources is to assist farmers in purchasing agricultural machinery to increase post-harvest capacity and establish cold storage facilities, among other measures.

According to the Statistical Committee, potatoes and wheat bread are the staple foods in Armenia.

In light of this, the deputy minister asked his British colleagues if bread products and potatoes are the most consumed food in Armenia, should the government policy focus on producing and reducing prices for these two food products, the answer was that the policy should prioritize production of higher-value foods, such as meat, vegetables, dairy products and fruit. They explained that this will not only lead to a decrease in prices, but also make these foods more accessible to everyone.

Armenia is a nation currently in a state of war. Given the ongoing geopolitical volatility, it is important for Armenia to adopt an austerity mode. Shouldn’t the government recognize the need to transition to an “emergency” mode of food consumption during emergency situations?

Arman Khojoyan does not see the need to switch to an austerity mode, and adds that the country did not implement austerity during the 2020 war.

We often look to Singapore and Israel as examples for various aspects of Armenian reality. Singapore currently has the highest level of food security, despite having no agriculture of its own. It relies heavily on imports to meet its food demand. According to the Samvel Avetisyan, implementing such a policy in Armenia would be challenging, even with significant financial resources.

“It is crucial to provide farmers with access to advanced technologies. Currently, farmers lack advisory and informational support,” Avetisyan says. “Israel has provided solutions in various areas, ranging from advanced machinery to water-saving systems and seed farming. They have solutions for every problem. Israel focuses on producing goods that are profitable for export.”

Law & Society

Resolving the Unresolved Issue of Garbage

Despite several legislative regulations, adopted strategies and promises, waste management continues to be unresolved in Armenia. Hasmik Baleyan explains.

Read moreNurturing a Culture of Giving Back: The New Law on Voluntary Work

Volunteering has become widespread in Armenia in recent years. However, it has only recently received legal regulation. The critical role of volunteers became especially evident after the Azerbaijani attack on Artsakh on September 19, 2023.

Read moreMission Incomplete: Armenian Police Reforms

The Pashinyan Government's reforms of the police and other institutions promised to bring long-awaited changes to Armenia. While some progress was registered, there have been setbacks and backsliding, particularly after the defeat in the 2020 Artsakh War. Police reform has been no exception.

Read moreA Fancy Resort, Protesting Villagers and Politics on Mount Aragats

Armenia’s newest ski resort, located on the slopes of Mount Aragats, partially opened last year. While Myler Mountain Resort is expected to become a hub for winter sports enthusiasts, complaints from villagers about the way it is being developed have gone unheeded.

Read moreWhen Untreated Sewage Is Dumped Into Water Resources

Most settlements in Armenia lack proper sewerage systems. Even when such systems exist, the scarcity of sewage treatment plants leads to untreated waste being dumped into water resources.

Read moreThe Rise of E-Scooters in Armenia: Creating Solutions or Problems?

E-scooters first appeared in the streets of Yerevan in 2021. With heavy traffic in the city center, they have become an ideal mode of transportation for short-distance commutes, however, not everyone agrees.

Read moreArmenia’s Plan for Universal Health Insurance

Access to quality healthcare is a fundamental human right, but remains an unattainable luxury for many in Armenia. As a result, some families find themselves in poverty because of the exorbitant costs of health treatments.

Read more