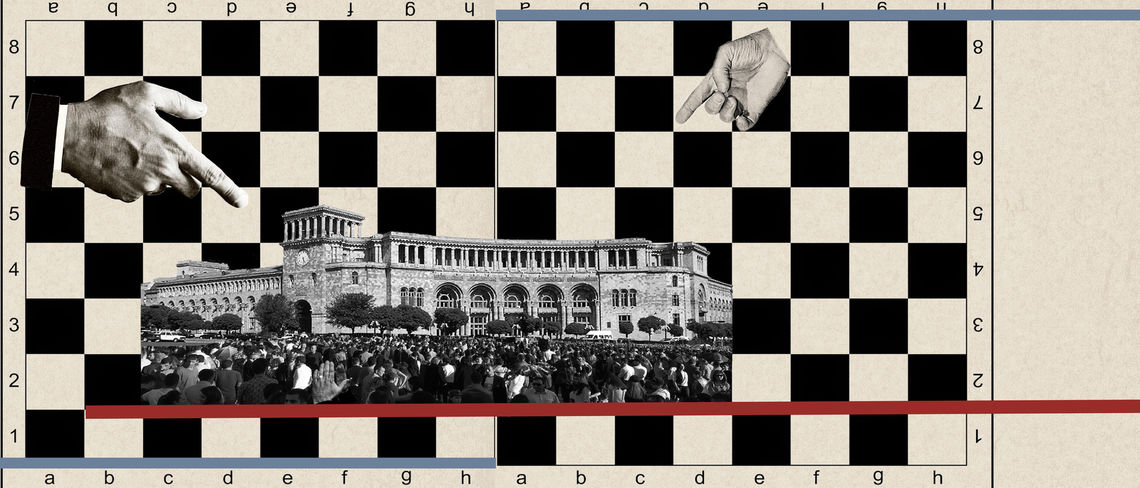

Opponents and critics of Armenia’s post-Velvet Revolution political establishment have relied on three main arguments in their attempts to question the legitimacy and broad mandate of the Pashinyan Administration. The first argument is hinged on the populism narrative, the second argument promotes the “democratic backsliding” narrative, and the third argument advances the polarization narrative. The underlying presupposition of these arguments not only question the will and character of the Armenian people, but also suggests a condescending and dismissive attitude towards Armenian political society. Collectively, these arguments assume that the Armenian electorate is composed of a naive, ill-informed citizenry that was easily duped by a dishonest demagogue. After all, this is the only way that these critics can justify Prime Minister Pashinyan’s electoral dominance and continuous, unprecedented popularity. More so, this is the only way that these critics can explain society’s “support” for Armenia’s “democratic backsliding.” When these narratives are deconstructed, however, the arguments of these critics are reduced to a singular premise: The Armenian public is fundamentally ignorant and must be rescued from itself. The democratic ethos and political will of Armenian society is marginalized: Armenian society is too unenlightened to understand the ethics of democracy or properly express its political will. Simply put, for these critics, the Armenian citizen is a tool.

Cloistering their arguments in generic claims of populism, or frivolous interpretations of legality and constitutionality, they seek to delegitimize the democratically-elected political leadership by normatively questioning the very ethics of legitimacy: the Armenian people do not know what is good for them. By denying the Armenian citizen agency, they are attempting to superimpose a culture of apathy. Needless to say, not only is this insulting to the dignity of the Armenian citizen, but it also entails an anti-democratic axiom. Consumed by their innate autocratic tendencies, these critics qualify the Armenian voter as a gullible simpleton, a blind cheerleader that must be saved from the clutches of Pashinyan’s manipulative rhetoric. That these critics, both in Armenia and in parts of the Diaspora, have been profoundly rejected by Armenian society speaks for itself. Confined to the fringes of Armenia’s polity, they immensely struggle to find a foothold in the marketplace of democracy. Spurned by the voters, and detested for their brazen support of Armenia’s previous undemocratic regimes, they hover on the precipice of political irrelevance. Their state of political desperation leads them to only one avenue: implicitly questioning the political will of the people.

But merely qualifying these remnants of the previous regime, or their sympathizers and apologists, as politically irrelevant, does not, in of itself, make their claims any less true. Yes, they have become politically irrelevant and they do lurk at the fringes of political society. Society’s rejection of them, however, is not the same as an intellectual refutation of their claims. What refutes their claims are the two broad developments observed in Armenia after the Velvet Revolution: 1) the burgeoning of democratic political culture,[1] and 2) growth of institutional trust.[2] For societies that experience populism, democratic backsliding, and polarization, the opposite is the case: democratic political culture decays, while institutional trust declines and is replaced by tribalism and cult-of-personality attributes. Considering how the trajectory of Armenia’s political culture is moving, empirical findings categorically reject the arguments posited by opponents and critics of the post-Velvet Revolution political establishment.

Burgeoning Democratic Political Culture

The recent Caucus Barometer survey provides a trove of data offering empirical findings that robustly support the democratization of Armenia’s political culture. Analytical considerations have denoted the sturdy civic culture of Armenian society that brought about the Velvet Revolution. This was the seed that grew the country’s democratic culture. My initial scope of analysis begins with public expectations after the Velvet Revolution, where survey findings show that 84% of society expressed positive expectations, with only 3% holding a negative view. This immense vote of confidence in the democratization process is supplemented by a subsequent question asking if the said expectations were met, with a resounding 74% noting confirmation, while 20% recording expectations were met “a bit,” and only 6% responding “not at all.” This substantial endorsement of a democratizing culture is aligned with society’s positive outlook for the future of the country: 80% of Armenian society holds that the situation in the country will improve, while only 15% is pessimistic. When compared to the same results from 2017, only 47% were optimistic, while 46% remained pessimistic about the country’s outlook under the then-undemocratic Sargsyan Government. This overall qualitative positivity is further confirmed when citizens gauge the direction in which the country’s domestic politics are going: 68% confirmed it is going in the right direction, with only 9% voicing the opposite. Compared to the pre-Velvet Revolution results from 2017, only 9% of society thought domestic politics was going in the right direction. That society’s outlook can change from an abysmal 9% to an emphatic 68% is quite telling and further confirmation of a political cultural shift. Reifying this embrace of democratic political culture is the general perception on democracy: 63% of society considers democracy “preferable to any other government,” with 14% suggesting uncertainty, and 15% displaying indifference.

Further findings demonstrate that this burgeoning democratic culture is not simply temporary or euphoric. While a resounding 85% affirms that Armenia is a democratic society, this affirmation is tempered by a set of pragmatic observations: 37% concede that while Armenia is a democracy, it does have “major problems,” 30% hold it is a democracy with “minor” problems, and only 18% hold that Armenia is a “full democracy.” Society’s healthy and diverse perceptions of its democracy, and the realization that it is a work in progress, further solidifies the democratic ethos of Armenia’s growing political culture. Individual indicators also confirm this assumption. With respect to freedom of speech, 89% of society confirms that “people have the right to openly say what they think,” an extraordinarily important indicator of democratic culture. A more important individual indicator, and one less abstract, is the sense of fairness in one’s treatment by the government. Asked if one considers one’s self “treated fairly by the government,” 67% of society confirms fair treatment, a healthy indicator of democratic governance. In comparison to the 2017 results, only 18% confirmed fair treatment, while 74% of society confirmed unfair treatment under the Sargsyan Government. Contextually, when qualitative and numerical indicators demonstrate a positive directional trajectory, the very discussion of “democratic backsliding” suffers from factual and empirical deficiencies.

Collectively, whereas societies that undergo democratic backsliding observe a decline in democratic political culture, Armenia demonstrates the very opposite. Since the Velvet Revolution, Armenia is experiencing a burgeoning democratic culture, as its society’s political values are being aligned with democratic principles. Further noting the positive correlation between these findings and society’s support for the post-Velvet Revolution Government, the reinforcement of Armenia’s democratic political culture is intertwined with the Pashinyan Administration’s democratic governance.

Growth of Institutional Trust

A healthy democratic political culture cannot develop without the formation of strong citizen trust in the political system and the institutions of that system. In the democratization literature, one of the most important indicators that distinguishes democratized societies from democratizing or non-democratic societies is the magnitude of institutional trust. The higher the interpersonal trust citizens have of their political institutions, the more democratic the given society remains. The lower the interpersonal trust that citizens have of their political institutions, less democratic, or non-democratic, those given societies remain. Furthermore, in societies where institutional trust is high, accusations of populism become inherently problematic, for populist leaders consistently seek to dismantle institutions. As such, populists do not and cannot promote the strengthening of democratic institutions, and for this reason, they devalue institutional trust. In this context, the prevalence of populism or democratic backsliding is best gauged by observing declines in democratic political culture as well as low-levels of institutional trust. As has been demonstrated, Armenia’s democratic political culture is acutely on the rise, displaying a robust positive trajectory. Similarly, the data unequivocally demonstrates enhanced trust by citizens towards Armenia’s political institutions. Collectively, empirical findings counteract any claims of democratic backsliding or populist, “mob rule.” The results are quite conclusive: increase in institutional trust highly correlates with perceptions of legitimacy that Armenian society has towards its political leadership.

Survey data shows that Armenians hold high levels of trust for both political institutions as well as the state’s security apparatus.[3] This is inherently important because prior to the Velvet Revolution, both the country’s political institutions as well as its security apparatus suffered from severe citizen distrust. The current Government, for example, enjoys a 71% level of trust, exceedingly high by any democratic standards. This is corroborated by the recent European Commission’s EU Neighbors Annual Survey of Armenia, where citizen trust toward the Government is 76%,[4] higher than the Caucasus Barometer. The pre-Velvet Revolution Government, on the other hand, suffered from abysmal levels of distrust: President Sargsyan was distrusted by 65% (trust 17%) of society,while his Government was distrusted by 59% (trust 20%). For a society to go from trust levels in the low 20 percentile to one exceeding 70% is a strong measure of citizen confidence in its political leadership. Levels of trust for the legislature have also shown an immense improvement, going from 12% in 2017 to 39% in 2020. But more telling is the decline in the levels of distrust: the pre-Velvet Revolution Parliament was distrusted by 66% of society, while the current Parliament’s level of distrust is less than half of that at 30%. This demonstrates a qualitative improvement in institutional trust, as society went from having a negative 66% distrust level to a positive 39% trust level. The EU Commission’s survey finds even higher levels of trust for the current Parliament, recording a citizen trust level of 59%.

Perhaps the most profound measure of enhanced citizen trust in Armenia’s state institutions is the sizable change of trust towards the Police. Along with the judiciary, the Police remained one of the most despised and distrusted state institutions. Tracing the data back by a decade, the public’s distrust of the police averaged around 40%, while distrust levels in 2017 alone stood at 46%. Trust levels, on the other hand, stood at the upper 20 percentile, with the trust level in 2017 at 29%. Such low levels of trust in Armenia were consistent with findings in most non-democratic societies, as police were distrusted for being servants of the political elite. The recent results, however, have profoundly transformed this trend, demonstrating a large shift in public trust towards the institution of the Police. Citizen distrust of the Police stands at 22%, the lowest level in the polling history of the Caucasus Barometer, while trust of Police stands at 51%, the highest level of trust recorded since Armenia’s Independence. The findings, to this end, are quite conclusive: that one of the most detested and distrusted institutions in recent history now enjoys majority public trust is a powerful indicator of how impressive the growth of institutional trust has become under the post-Velvet Revolution Government.

The False Polarization Narrative and Political Noise

One of the broader misconceptions concerning the political situation in Armenia has been the application of the term polarization. Misused and misunderstood, the concept has been incorrectly utilized to explain developments and dynamics in Armenia’s political field. In political science, polarization fundamentally entails a relatively balanced split within society, where each pole, or side, holds profoundly different and uncompromising political and cultural views. The concept, therefore, presupposes relatively equal portions of the population polarized into diverging sides. As the data clearly shows, Armenia is not a polarized society. When over 70% of society supports the political leadership, while a trivial 11% does not, it becomes incoherent to speak of polarization. Armenian society is neither polarized nor split—rather, Armenian society, for the first time since the Karabakh Movement, is overwhelmingly united. Consequently, falsely advancing the polarization narrative not only suggests a misunderstanding of the concept, but it also suggests a false equivalency: it qualifies the fringe 11% as a pole. Thus, politically marginalized and electorally irrelevant forces, through the narrative of polarization, inflate and hyperbolize their socio-political relevance. The fringe 11% frames itself as the polar equal of the 70%. Needless to say, such framing borders the nonsensical; however, through this framing, these fringe forces are able to make a great deal of political noise. This noise has been quite evident in their opposition to institutional reforms as well as their vehement opposition to holding the corrupt elite accountable.

Such opposition, however, contradicts the political will of the Armenian people. As survey findings demonstrate, this distorted political noise runs counter to the demands of Armenian society. Armenia society, for example, is adamant in its demand for judicial reforms, as it fundamentally lacks trust in this institution. Yet anti-Government forces qualify any attempts at reform as populist and unconstitutional. But the empirical findings are quite damning. 48% of society has no trust in the court system, with only a mere quarter of the public displaying some trust. 61% of society deems the court system as unfair and arbitrarily biased, with only 21% gauging some level of fairness. This distrust of the judicial system is further reified by public demand for reforms: 66% supported the proposed Constitutional referendum to remove seven of the Constitutional Court judges that were remnants of the previous regimes. Similarly, 66% favor the vetting of judges, an important transitional justice mechanism that will cleanse the judiciary of systemic corruption. Collectively, not only is there an incommensurability between the demands of Armenia society and the positions of anti-Government forces, there is also the fundamental problem of constructing false narratives that undermine the will of Armenian society.

The disconnect between the narratives of anti-Government forces and the stipulations of Armenian society clearly discredit the former. There is no empirical support for claims of polarization, populism, or democratic backsliding. As the survey results demonstrate, the demands of the Armenian people are overwhelmingly aligned with the policies of the Armenian Government, or to put it more succinctly, the Armenian Government conforms and serves the will and expectations of the Armenian people. This, to a large extent, better explains why the political noise created by these fringe groups fails to resonate with society: they simply run counter to the interests of the public. A case in point is the fervent defense that these forces mount in support of the previous political elite whose system of corruption and impunity suppressed Armenian society. As the current government proceeds to investigate and hold such culprits accountable, anti-Government forces reproduce the narrative that these criminal investigations are politicized acts of persecution. Such political noise, again, runs counter to the demands of Armenian society: a massive 78% approve the Government’s prosecution “of the representatives and leaders” of the previous regime, while only 13% disapproves of such measures. In this context, seeking to construct false narratives and forcefully deliver them through amplified political noise has simply become counter-productive.

A Futile Endgame

What are the configurations of these anti-Government forces? At the present, anti-Government forces are primarily comprised of far-right groups, illiberal NGOs, and three visible political parties: Republican Party of Armenia (RPA), Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF), and Prosperous Armenia Party (PAP). PAP joined the anti-Government forces only recently, while the remaining groupings have been important amplifiers of anti-Government narratives. I use the phrase anti-Government forces as an umbrella term, meaning that all of these groups are not aligned with one another, nor do they all coordinate their anti-Government activities. The right-wing groups, for example, deemed rather extreme in their racism and sexism, do not openly collaborate with the political parties, while the illiberal NGOs, being funded by resourceful proponents of the previous regimes, selectively align with either of these groups on an ad-hoc basis. The three political parties, however, having formed the dominant coalition during the previous regime, are in fact tacitly aligned together to advance their anti-Government initiatives. The problem with these groups, of course, is that they have very little public support. Both the ARF and the RPA barely garner 1% support, respectively, while PAP secures 10% popularity.[5] To this end, even when aggregating the electoral strength of the three anti-Government parties, they barely garner 12% public support. This is what substantiates their relegation to the fringes of political society.

Even when operating from the fringes, these opponents and critics have every right to express their objections and to challenge the policies of the Government, for a healthy discourse on societal issues is inherent to a democratic project. But the general discourse from these opponents has neither been honest nor intellectually sustainable—facts and empirical trends are ignored in favor of perfidious verbosity. The false narratives of polarization, populism, “mob rule,” or democratic backsliding are easily falsified by the empirical realities: Armenia’s democratic political culture and enhanced institutional trust. Thus, detached from reality, these attacks have been primarily visceral and resentful, for their objective has never been to promote constructive social discourse; to the contrary, the objective has been the toppling of the current Government. In this context, there is a difference between disagreeing and challenging the Government’s policies as opposed to seeking to depose (legally or extralegally) a democratically-elected government. This latter desire is clearly indicative of the complete lack of respect that anti-Government forces have for the will of the Armenian people. And as the large body of empirical findings demonstrate, Armenian society categorically rejects both the narratives and the aspirations of these forces.

It is really difficult for Armenian society to swallow the faux morality and artificial democratic ethos of these critics, especially when these were the same operatives that propped up, supported, and reinforced the undemocratic system that suppressed Armenian society for more than two decades. That closet proponents of authoritarianism are now demonstrating “concerns” for Armenia’s democracy, and that the same people who made a mockery of democracy are now lamenting an imaginary backsliding, is intellectually insulting to the Armenian citizen. In this light, I would like to note that this refutation of the Government’s opponents should not be qualified as a defense of the Pashinyan Government. This Government is here today, but it may not be here tomorrow, proverbially speaking. This refutation, unequivocally, is a defense of the will of the Armenian citizen: political society must respect and abide by this sacred will. It is this utter disdain for the people’s will that has hurled these opponents and critics to the fringes of political society. The people have spoken, yet listening to the people is an alien concept to these forces. Be that as it may, but they must come to one final realization: the era of disenfranchising Armenian society is long gone.

also read

A Pre-Pandemic Survey Reveals a Generally Optimistic Population

The Caucasus Barometer survey conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic gripped the country, reveals that the overall mood of the Armenian public was optimistic.

Read morePolice as Public Servants: A New Armenian Model?

Armenia’s Government approved the Strategy on Armenian Police Reform and its accompanying action plan back in April. Will the implementation of this new strategy help to heal decades of mistrust?

Read moreNegating the Honeymoon Discourse

The International Republican Institute recently published its fourth public opinion survey since the Velvet Revolution. The survey found that a healthy majority of Armenians believe the country is heading in the right direction.

Read moreFrom Protecting the Corrupt to Punishing the Corrupt (or It Seems)

Can the popularity of the National Security Service be sustained after the dismissal of Artur Vanetsyan? It can, but only through one mechanism: rigid institutionalization and the complete alleviation of the personalization of politics in Armenia.

Read moreby the same author

Resolving the Constitutional Court’s Crisis of Legitimacy

During an extraordinary session, Armenia’s National Assembly initiated and unanimously approved a set of Constitutional amendments to address the crisis of political and institutional legitimacy of the Constitutional Court.

Read moreThick as Thieves: Bringing Armenia’s Robber Barons to Justice

The Armenian government has initiated a broad set of cases against the oligarchs and Robber Barons of the former regime composed of the upper echelon of the previous-pyramid hierarchy. Nerses Kopalyan looks at a number of high-profile cases.

Read moreArmenia Gets Serious About Reforms: Making Sense Out of Vetting

As an instrument of transitional justice, vetting is designed to “cleanse” state institutions that are tainted by systemic corruption, nepotism, and incompetence. Vetting of personnel is the first step toward the broader goal of institutional reform, writes Dr. Nerses Kopalyan.

Read more