Listen to the article.

Some of our compatriots, especially those who live outside Armenia, are not very clear about what is happening in the Tavush region of the country and the opposition is offering half-truths and even false information about the situation.

First of all, let us establish a few international rules.

- If one country occupies another’s settlements or villages, this act is governed by specific rules. Occupation itself is not illegal under international law, but it must adhere to certain conditions, including that it must be temporary in nature and entail the protection of civilians and their properties. Even if these areas are devoid of population, the occupation can still infringe upon human rights if it prevents the displaced population from returning to their homes or violates their rights in other ways.

- But if the initial act of occupation occurs without a valid justification under international law (such as unprovoked aggression rather than self-defense or a sanctioned international intervention), the occupation is considered illegal from the outset. In such a case, the occupation of a neighbouring country’s territories, even if these areas lack settlements, is considered under international law as an act of aggression and can be illegal. Although direct implications for human rights may not be as immediate or apparent as in the first scenario, such acts impact the rights of the occupied state and its people, potentially leading to long-term human rights consequences indirectly related to the occupation.

The Situation of the 1991 Soviet Maps

The Soviet borders between Armenia and Azerbaijan in Tavush region, and the Armenian highway, existed until independence. These borders were delineated by the Soviet General Staff and detailed maps, which are entitled Secret, were accessible only to a few politicians and individuals who had the necessary security clearance.

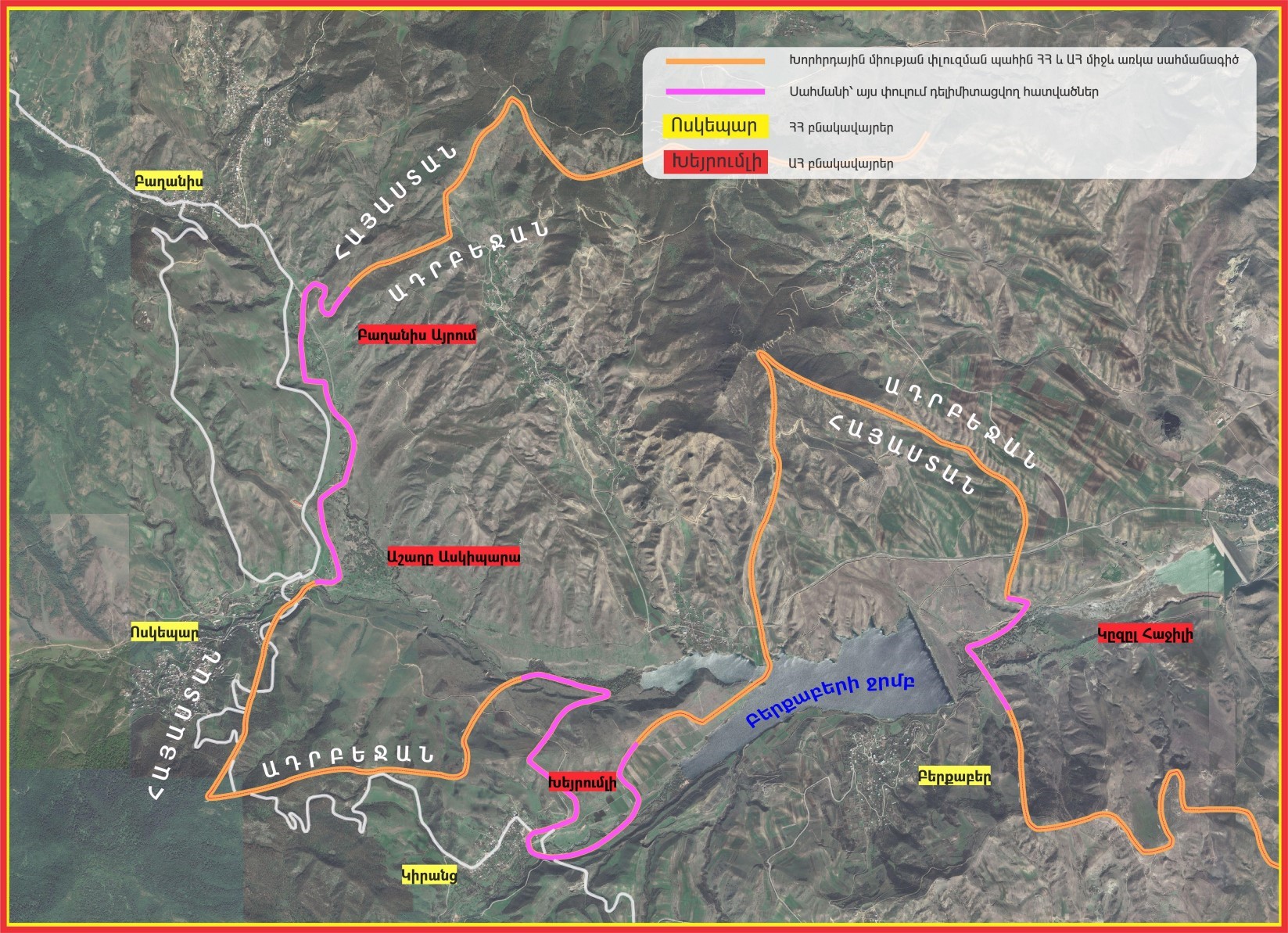

Map N1 can be seen on Google Maps. It depicts the actual borders and roads in recent years. It shows the Soviet era-delineated borders, which are of unusually irregular construction and route, thus causing the Armenian highway connecting Ijevan to Noyemberyan to cross the border four times, passing over into Azerbaijani territory and returning to Armenia. For long stretches the Armenian highway was running very close to the border or next to the Azerbaijani villages of Ashaghi Askipara and Baghanis-Ayrum. In fact, even according to the Soviet Military maps, the western strip of the village of Ashaghi Askipara and half of Baghanis-Ayrum belonged to Armenia.

In some short stretches the border is actually the road between the two republics, a situation which contradicts all sorts of international regulations and logic, which the USSR had been using in many locations, especially on the road from Goris to Kapan in Syunik region.

Map N1: The map of Tavush region, as shown in the media in April 2024.

As can be seen on Map N2 (a simplified version of Map N1), the road connecting Ijevan to Tbilisi, before entering the Armenian village of Voskepar, at four points crosses over into the Azerbaijani territory and comes back to Armenia. Furthermore, north of the Ashagi Askipara village, for a few kilometres the main road runs next to and parallel to the border.

It is abundantly clear that during hostilities, Azerbaijani forces could and did target all local and international trucks and other vehicles on the Armenian highway, resulting in casualties.

If we return to the Soviet period, this presented no problem, since these republics were both part of the USSR’s “brotherly” countries. After the initial period of independence, Armenian forces took control of these lands and the question of ownership was still not properly addressed.

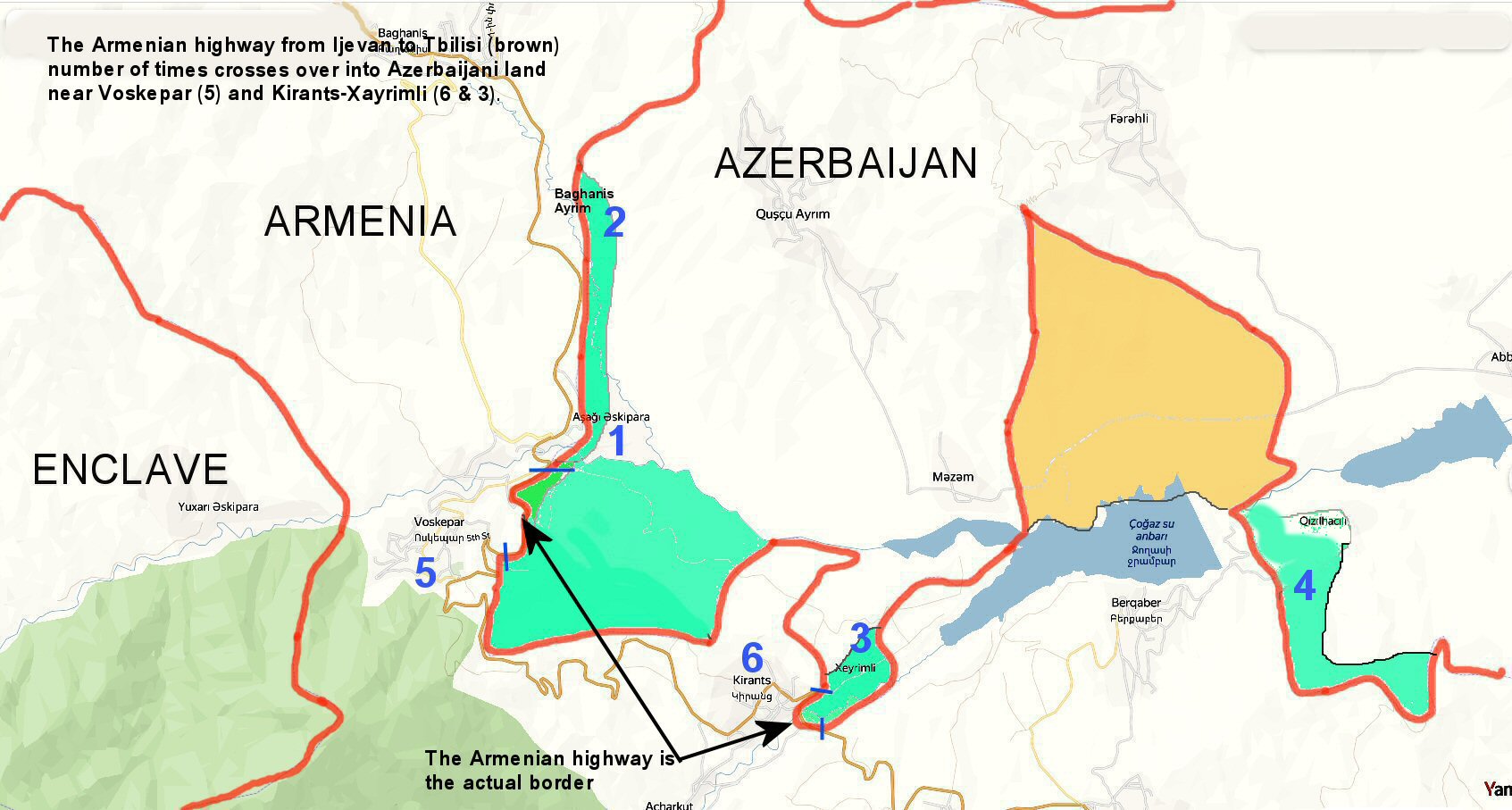

Map N2 is a simple one, showing the borders, roads and the points where the road crosses over into Azerbaijani territory with red dots.

Developments in 1992

As previously mentioned, at the start of hostilities, Azerbaijani forces positioned beyond the border began shooting at drivers of cars, tankers, and lorries traveling along the Armenian highway.

These lorries and tankers included many international transporters traveling through Armenia. Therefore, to ensure safe passage near the Azerbaijani border and where the road crosses into Azerbaijani territory, a solution needed to be found. After the first year of the war, because of continued sporadic shooting by Azerbaijani forces in these regions, it was decided to take the minimum measures necessary to ensure the safe passage of the transport over Armenian roads, by taking control of some of the lands adjacent to the borders.

In order to have a secure highway, the Armenian side took a strip of Azerbaijani land east of the highway under their control, so that the traffic on the Armenian road would have some sort of safety. Therefore, in order to secure the safety of the passage, strips of land between points 1 and 2, as well as the plot south of point 2, where the roads repeatedly cross over to Azerbaijani territory, had to be brought under Armenian control. Additionally, for the security of the road, between points 1 and 2, east of the green strip, the Armenian army built a strong defense line.

On Map N3, these strips of lands taken over by the Armenians are shown in green. This also applied to the lands near the Azerbaijani villages of Kheyrmli next to the Armenian village of Kirants, as well as Kizilhacilli, near Berkaber, where Azerbaijan had occupied Armenian lands colored yellow. The Kirants bridge was taken over by Armenia as the bridge and a small piece of land around it had been given to Azerbaijan by the Soviet authorities. An illogical decision, as the road and the bridge were only connecting the Armenian village of Kirants with the highway.

The population of the two Azerbaijani-Armenian villages of Ashaghi-Askpara and Baghanis-Ayrum were derelict, and the two Azerbaijani villages of Kheyrmili and Kizilhacilli had left their villages and at present there are no standing buildings. Therefore, the four villages had been devoid of population. The buildings of the small village of Kheyrmli had been left to the elements, and the makeshift buildings had disappeared, so much so that today Google Maps does not even show a trace of this village on their maps, only pointing to where it had been located.

This was the status of the Tavush region from 1992 until March of 2024.

Map N3 shows the regions, which Armenian forces had taken under their control to ensure the safety of the Armenian highway.

Aliyev’s Change of Mind

Until 2024, Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev was strongly opposed to accepting the border stipulated by the Alma-Ata Protocol, saying that they may decide to fall back to the borders drawn at other times. In such a case, Armenia could also have proposed to accept the 1926 borders, whereby the area of Armenia was almost 31,000 km2.

Early in 2024, President Aliyev announced that he was accepting the borders mentioned in the 1991 Alma Ata protocol. This was shortly followed by his demand that Armenia should immediately return the four Azerbaijani villages of Ashaghi Askipara (in fact over 10% Armenian), Baghanis-Ayrum (in fact half Armenian), Kheyrimili and Kizilhacilli.

The truth is that Azerbaijan was not at all interested in getting back those abandoned and empty villages, where in the small ones there was not even a building intact. His main reason was the neutralization of the Armenian defense lines built just east of the green strip on Map N3.

In case Armenia does not agree to return the villages, Azerbaijan might have contemplated initiating a case against Armenia before the European Court of Human Rights, to allege that Armenia disregarded the human rights of the population of those four villages.

In return, Armenia could not complain in a similar manner, since although Azerbaijan has occupied over 200 km2 of Armenian territory, they contained no settlements to be occupied by Azerbaijan. Nevertheless, Armenia could contemplate a countercase. Although there may be a case against Azerbaijan, claiming that from these occupied heights, Azerbaijan effectively controls the fields, orchards and lands of the Armenian villagers, who they keep under constant threat by sniper fire and indirect harassment.

These are the villages that Armenia’s Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan referred to, when talking about the 31 village lands.

In Tavush, having agreed to the Azerbaijani proposal to demarcate the border with the maps delineated by the Soviet Military Staff ruling at the time of the Protocol, Armenia abides by the Alma-Ata Protocol and expects Azerbaijan to do so in the following regions, as officially agreed.

1 – Return to Armenia the 8.5 km2 lands north of the Berkaber reservoir, marked yellow on Map N3.

2 – Return to Armenia all the territories forcibly taken from Armenia during the incursions of May 2021 and September 2022 shown on Map N4. This has been agreed to by Aliyev as part of the agreed deal.

Map N4: Regions of Armenia occupied by Azerbaijan between May 2021 and September 2022, coloured violet and orange.

The Problem of Kirants and Its Bridge

Map N5 is a detail taken from the Soviet Military Staff map dated 1990. On this map the border between Armenia and Azerbaijan is the one agreed to during the 1970s and also referred to in the maps in the 1991 Alma-Ata Protocol, through which Armenia and Azerbaijan became independent republics.

As described in Map N3, the border is intentionally extended southwest to give Azerbaijan a short section of the Armenian highway, including the bridge, thereby allowing them to control access to the village.

Handing over the road and the bridge to Azerbaijan could not be accepted, as it would make the road unusable for the Armenians. There could only be two solutions. Through negotiations with Azerbaijan, their territory surrounding the road and village were handed over to Armenia, in exchange for similarly sized Armenian land to be given to Azerbaijan. However, it is unlikely that Azerbaijan would accept such a solution as their actions and announcements illustrate that they are mainly interested in creating problems for Armenia.

Map N5: Detail from Soviet Military Staff map of 1990,

showing the border and the Armenian highway.

The alternative would be to reroute the road and bridge, ensuring highway access to Kirants via a new road that avoids the Azerbaijani border. This is the solution implemented by the Armenian authorities.

This solution would resolve the access to Kirants, but the psychological problem for the Armenians of this village, having to live 200 meters from the Azerbaijanis could not be deemed as an agreeable one. Of course it would possibly be the same for the Azerbaijanis, who are to be settled in, or near the site of the old village of Kheyrmli.