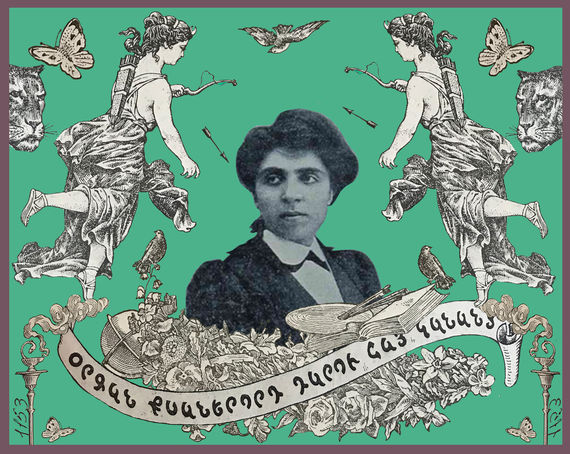

Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

More than a century ago, when the Armenian nation was experiencing one of the darkest times of its history, Armenian women stood up and undertook the mission of educators and caretakers. Once silenced and controlled by men, they courageously raised their voices and spoke boldly about women’s issues, established magazines and journals, educated girls, made calls for action and took care of thousands of orphans… They acted.

Writer, poet, essayist and public figure Zaruhi Kalemkearian was among them. Once a beloved writer widely known in Armenian communities around the world, Kalemkearian today, is remembered by only a few.

As one of the first Armenian feminist writers, Zaruhi left a rich legacy including articles, essays, memoirs and poems. Today, more than ever before, as the Armenian nation is trying to reconcile with its past, it is time to rediscover voices like Zaruhi and embrace her ideas while building a better future.

Zaruhi Kalemkearian (nee Seferian) was born on July 18, 1874, in Constantinople, to the family of Ashot Seferian and Beruze Temirjipashean. As a daughter of a wealthy merchant, she grew up in comfort on the shores of the Sea of Marmara in the Kadıköy neighborhood of Constantinople.

At the age of seven, Zaruhi entered Agha Taii’s school and later continued her education at the Aramean College in Constantinople which played a crucial role in her development. In her memoir “From the Road of My Life,”[1] Zaruhi writes that Aramean College was her second home. While there, she started to show a certain interest in literature and wrote her very first short poems.

Kalemkearian grew up in an intellectual environment. She was the niece of famous Armenian writer Yeghia Temirjipashean who had a significant impact on her growth as a writer and an intellectual/public figure. At the beginning of the 1890s, Zaruhi published her poems in a number of newspapers, including the “Manzume Etkyar”[2] and “Byzandion” [3] under the pseudonym of Euterpe (the muse of poems and music in Greek mythology). Moreover, between 1892 and 1894, she published three books of poems entitled “Nvagn Yevterpya” (Euterpe’s Song), “Mrmunj” (Whisper), and “Zartonk” (Awakening).

Zaruhi was greatly inspired by French literature of the time, therefore it is no surprise that the main themes of her poems were love, the tragedy of people, and social injustice. However, these topics were not greatly welcomed by the male-dominated intellectuals. In her article “Armenian Women’s Writing in the Ottoman Empire, Late 19th to Early 20th Centuries,”[4] Dr. Hasmik Khalapyan explains that during the late 19th century, national identity, culture, family as well as education were the most important issues being discussed within Armenian society. In this regard, Armenian female authors had a special mission and “they were called on to participate in the public debates both as reformed and reformer women.”

Zaruhi was not an exception. After publishing her first book of poems, Byuzand Kechean, editor of Byzandion told her to concentrate on the most important aspects of a woman’s life – family and children – instead of writing about flowers, sea, sunlight and birds.

He told me to write especially about a woman’s role within the household, and the immediate aspects that inspire familial happiness – a woman’s smile, charm, kindness, sacrifice, love. Kechean told me to get into family circles. Terrified of the relentless criticism of society, a young girl couldn’t sing the song of her heart.

In the beginning of the 20th century, women’s sections in different magazines and women’s journals emerged in Constantinople, providing a new and independent platform for women writers to freely express their ideas. Emerging Armenian women writers started to actively talk about feminism, women’s rights and demanded independence. Along with writers Haykanush Mark (1884–1966) and Anayis (1872-1950), Zaruhi was one of the most active female voices. She launched the first women’s section in one of the most popular daily newspapers, becoming the first-ever woman in Constantinople to do so.

Nonetheless, the career of a writer was not an easy path for a woman: because of the conservative views and prejudices within society, Zaruhi constantly faced difficulties. As a regular contributor to periodicals, she was earning a decent salary which was quite rare for women of that time. However, Zaruhi’s family was not particularly happy about it: earning money for their expenses was considered to be quite humiliating for women.

Since I was a girl from a wealthy family, my parents could not reconcile themselves with the fact that I was earning money. My mother, who was a trustee of the National Hospital, would spend my salary buying candies and sweets for people who were there.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Constantinople was a vibrant intellectual hub and as an emerging writer, Zaruhi was at the heart of it. Many Armenians, who had the opportunity to travel outside the Ottoman Empire and became familiarized with European customs and manners, used to hold Parisian-style intellectual gatherings, salons, where young people would exchange ideas and discuss literature, music and politics. According to Zaruhi, those salons provided a platform for intellectual discussions and debates, welcomed, and encouraged women to speak publicly on different topics.

In those salons, conversations around national topics were being held, ideas about literary and artistic texts were being exchanged, poetry was recited, there was music and high intellectual pleasures, dance.

Later, those gatherings played a notable role in shaping Zaruhi’s views about women and their role. As she recalls, many of the women attending salons were not keen on marriage and would rather concentrate on the socio-cultural life of their community and have their input in educating girls.

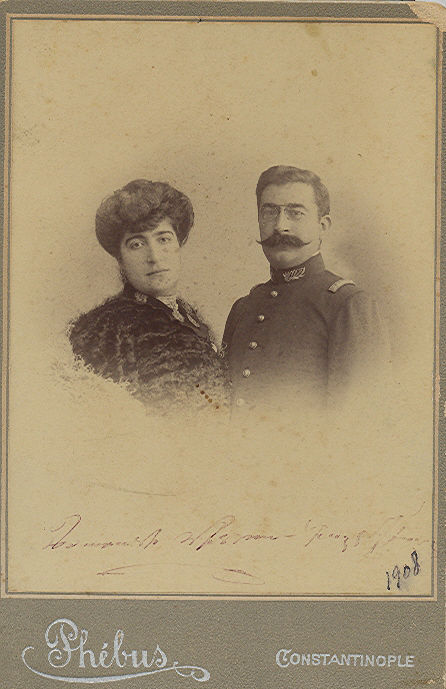

In 1898, during one of those gatherings, Zaruhi met Turkish army Colonel Mihran Kalemkearian and soon they got married. Interestingly, despite the conservative views in society, the Kalemkearians, who were quite progressive, welcomed Zaruhi’s career as a writer and encouraged her to be publicly active and contribute to community life.

During the early 1900s, Zaruhi continued writing and was a regular contributor in a number of magazines including “Ardemis,” the first Armenian women’s periodical founded by writer and journalist Mari Beylerian. Her writings explored Armenian women’s role in society and within a family, motherhood, and Armenian women’s history. However, within several years, events began to unfold that would completely change Zaruhi’s life…

When the Armenian Genocide started, Zaruhi, along with her family, remained in Constantinople despite all the threats of the Turkish government. Because she was friends with many Armenian intellectuals, Zaruhi was constantly under Turkish police surveillance. As she recalled in her memoir, she had to destroy all the letters she had exchanged with them. Zaruhi even resorted to burning the writings of Yeghia Temirjipashean and disposing of books espousing patriotism to ensure her safety.

Despite the difficulties, Zaruhi did not sit idly by. As a patriot, she devoted herself to her nation and spared no effort to help those in need. In 1919, she became the head of the Armenian Red Cross branch hospital in Shishli and started taking care of orphans who had lost their families during the Armenian Genocide. While dedicating herself to humanitarian work, Zaruhi experienced the horrific reality of the massacres and did everything to provide comfort and love to many orphans.

I saw them with my eyes. And you, Armenian mothers, who have not seen this, go and touch that cruel reality, that painful and big wave of children who arrive and gather in the yards of churches. Go, mothers, and see this orphanhood. See their depressed faces, see their eyes frozen from the horror of the crime, look at them and let your soul rebel with a furious delirium….

No, we shall not abandon our orphans. We shall caress them like our children.

We shall speak to them.

-Where is your father, son?

-They slaughtered him…

-Where is your mother?

-She died on the road…

The next one answers the same and so you pass the lines of orphans who look at you broken-hearted.

In 1919, the Armenian Women’s Association (League) was established, which aimed to awaken the consciousness of Armenian women to their civil, political, and educational rights. [5] Zaruhi, one of the founding members, soon started to contribute to the association’s biweekly magazine “Hay Gin,” and wrote articles about feminism and Armenian women’s issues within society and called on women to act and help to revive the nation.

Zaruhi believed that education was key for young girls and for the future development of the Armenian nation. She was well aware of the feminist movements around the world and would educate her readers by bringing examples of Western women. In one of her articles, Zaruhi noted that there were women architects, doctors and lawyers in different parts of the world while the feminist concepts had just reached Armenian girls. She praised Armenian women and acknowledged the difficulties and hardships they endured emphasizing that it’s time for them to equally stand next to men and have their important role within society.

At the beginning of the 1920s, Zaruhi moved to the U.S. with her family, where she lived until her death. As she recalled, moving to the States liberated her from Turkish censorship and Turkish officers because of whom she lost many beloved friends and colleagues.

While in New York, Zaruhi started to engage in the life of the American-Armenian community and devoted herself to promoting Armenian culture. In the late 1920s, Zaruhi became the first female board member of the Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU) and later led the New York branch of the organization. During those years, Zaruhi also led the Constantinople Armenian Union.

Besides these activities, Kalemkerian traveled throughout the U.S, gave lectures about the Armenian women writers of Constantinople, talked about Armenian women’s role in society, and presented her research on writers Srbuhi Dussap and Raffi. From time to time, Zaruhi wrote articles for American-Armenian periodicals “Paikar,” “Hayastani Kochnak,” and “Lraber”.

Zaruhi Kalemkearian was a beloved member of the Armenian-American community. In 1943, AGBU organized a special event celebrating the 50th anniversary of her literary career and activities.

During her life in the U.S., Zaruhi published three books – “My Grandchild’s Book” in 1936, an account of her journey from Constantinople to New York, “From the Path of My Life,” in 1952, memoirs about her life and several short stories and “Days and Portraits,” in 1965, a memoir dedicated to writers Daniel Varujan, Avetik Isahakyan, Arshag Chopanian, and painter Panos Terlemezyan. Kalemkearian’s memoirs are an exceptional documentation of life in Constantinople during the first decades of the 20th century and give an insight into the Armenian intellectual circles of the times.

Zaruhi never traveled to Armenia. However, she always welcomed socialism and was well-known among the literary circles of Soviet Armenia. Zaruhi believed that being part of the Soviet Union was crucial for Armenia’s rebirth and development and highlighted its importance in some of her articles. In 1965, Haypethrat, the state publishing organization of Soviet Armenia published a book dedicated to Zaruhi’s life and work. The book “Zaruhi Kalemkearian: Selected Works” included a number of her poems, short stories, and some of her memoirs.

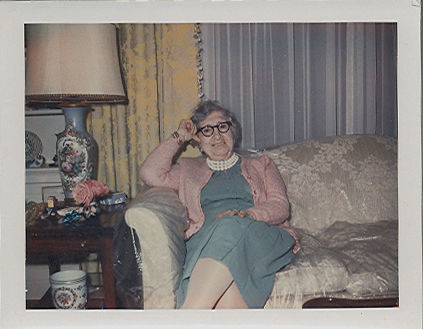

Zaruhi Kalemkearian died at the age of 97 in New York City. Today, her name is known to narrow groups of people, namely academics and literary critics. However, Zaruhi was an important public figure and educator whose legacy should hold a special place in textbooks and literary circles in Armenia and the Armenian Diaspora.

————————————-

1- “From the Road of My Life,” Zaruhi Kalemkerian, 1952, Antilias

2- Manzume Etkyar, a Turkish-language newspaper published in Armenian letters in Constantinople between 1866 to 1896

3- Byzandion, daily Armenian newspaper published in Constantinople between 1896-1918

4- “Armenian Women’s Writing in the Ottoman Empire, Late 19th to Early 20th Centuries,” Hasmik Khalapyan, 2019, EVN Report

5- Armenian Feminists: Hayganush Mark and Hay Gin, Lerna Ekmekcioglu