Domestic violence continues to be a serious issue not only in Armenia but around the world. According to a recent United Nations report, in 2021, more than 81,100 women were killed worldwide –– 45,000 of them by their partners or family members. In 2022, 16 women were killed in Armenia.

According to the Investigative Committee of Armenia, during the first half of 2022, 391 domestic violence criminal cases were examined, eight of which were murders, one of which was death due to negligence, 183 were assault cases, 11 were cases of committing severe physical pain or severe mental abuse, 51 were cases of threats to murder or causing serious harm to health or destruction of property.

From January to August 2022, domestic violence hotlines at the Coalition To Stop Violence Against Women received 4,808 calls. According to the organization, over the past several years, they have been receiving 4,000-5,000 calls throughout the year.

Irreversible

The latest case of femicide in Armenia in 2022 was reported on December 26. A day earlier, on December 25, a 38-year-old man in Vanadzor, shouting accusations at his wife, killed her with a kitchen knife. The man was arrested. On December 24, a 37-year-old woman was strangled to death in Gyumri; her 20-year-old boyfriend was arrested. On December 22, it was reported that a woman discovered the body of her 73-year-old mother with multiple injuries in Hrazdan. The daughter’s 49-year-old husband had gone to his mother-in-law’s apartment, argued with her about household issues, and then killed her by hitting her several times. On December 12, a 78-year-old woman was strangled to death by her sister’s 25-year-old grandson in the city of Abovyan.

On November 2, a resident of Vanadzor reported to the police that he had found the body of an 82-year-old woman who had allegedly taken her life in her apartment. It was soon revealed that the woman’s 18-year-old grandson had killed her. On October 6, a man killed his 37-year-old wife in Nubarashen. On August 27, police found the body of a 35-year-old woman with her head partially cut off in a house in the village of Arzakan (Kotayk region). A few days later, a 46-year-old resident of Arzakan admitted to killing his wife. On August 18, a man killed his 71-year-old wife by stabbing her several times in the village of Nor Geghi (Kotayk region), then committed suicide by jumping off a bridge. On August 12, a 55-year-old woman was found killed in her apartment on Komitas Avenue in Yerevan. After an investigation, her 17-year-old son was arrested on suspicion of killing her by strangling her with a rope. On August 11, three men strangled a 46-year-old woman from Yerevan’s Davtashen neighborhood. On June 21, in the village of Kharberd (Ararat region), a woman tried to intervene in a dispute between her son and husband, during which the husband deliberately struck his wife on the head, killing her. On May 22, a man killed his 42-year-old wife in the city of Gyumri. On May 5, a husband killed his 35-year-old wife in Yerevan. On April 22, a man killed his wife’s father and mother in Armavir region. Another case of murder took place on March 11 when a husband blew up his wife and himself with a grenade in the courtyard of their children’s school. On January 26, in Vanadzor, a 76-year-old husband killed his 70-year-old wife with sharp instruments and then dismembered her body.

Researching Domestic Violence

In 2022, the Statistical Committee of Armenia published the “Domestic Violence Against Women” Study. The study showed that 31.8% of the respondents were subjected to psychological abuse by their husbands/partners, 6.6% were victims of sexual abuse, and 14.8% of physical abuse.

A study conducted in 2021 that looked at women aged 15-59 in 2,872 households identified two types of physical abuse: moderate (slapping, throwing an object at a woman, pushing, pulling her hair) and severe (kicking, dragging, beating, strangling, and using weapons). Based on these markers, moderate abuse is more common at 13.1%, while cases of severe physical abuse are at 5.5%.

Defining sexual abuse is more difficult than physical abuse. The study notes that women had difficulty assessing whether they were sexually assaulted or not. In response to the question, “Have you ever had sexual relations when you didn’t want to, but agreed because you were afraid of what your partner might do if you refused?” women responded yes. Yet, they also stated that having sexual intercourse is part of their “marital duty” and cannot be considered abuse.

Among the respondents, 62.5% of the women who were subjected to sexual abuse were also physically abused, and 27.8% of those who were subjected to physical abuse were also sexually abused. A study that looked at women who have been in relationships and were physically and sexually abused shows that women in urban areas experience more sexual and physical abuse than those in rural areas.

“This may be due to the fact that women living in rural areas don’t really perceive such behavior from men to be abusive, or are more uncomfortable speaking about abuse,” the study explains.

Among those subjected to physical and sexual abuse, the highest percentage –– 22.4% –– includes those who have completed primary and elementary school or are still receiving an education.

The study also notes that despite the fact that 20.6% of women who at some point in their lives were sexually or physically abused by a partner or suffered some sort of injury, only 1% had injuries that required medical attention.

According to the study, only 12% of women who have been physically or sexually abused by their partner have sought help from a responsible institution. And 76.5% of women who have been physically or sexually abused by their partner continue to live with their abuser.

The study also states that 67% of women do nothing to protect themselves from abuse. Only 33% of women have ever fought back against abusive partners and 43.3% of abused women simply keep silent about the abuse.

The handbook “On Preventing and Combating Violence Against Women and Domestic Violence in Armenia” cites several reasons for this silence.

“Some women may perceive a cycle of abuse as something normal, especially if they grew up in a family where abuse took place,” the handbook explains. “Or, simply, they may not want to accept the reality in which they find themselves. Some women feel so helpless and humiliated by their inability to predict or control the abuse that they experience psychological crises.”

Some women often find it difficult to leave an abusive relationship due to social and economic factors such as lack of financial resources and because of social stigma and public perceptions.

Additionally, women who want to end an abusive relationship are usually reluctant to talk to friends and family members or to go to the police because they feel ashamed and humiliated. They also fear they would be pressured by their husbands, or that no one would believe them.

Those Who Speak Up

Even when survivors of abuse make the difficult decision to go to law enforcement, their cases are often not seen all the way through. In 2018, the Investigative Committee examined 519 criminal cases of domestic abuse, of which only 82 were sent to court with an indictment; 635 cases were examined in 2019, of which 326 were dismissed, while 128 were sent to court with an indictment. In 2020, 730 cases were examined of which 356 cases were dismissed, while 129 were sent to court with an indictment. This trend shows that most domestic violence cases are dismissed.

The report “Challenges and Gaps in the Response to Domestic Violence in the Republic of Armenia” published by the Coalition to Stop Violence Against Women in 2020 states, “When abusers are not brought to justice, that phenomenon is perceived as acceptable and tolerated within society. Such an approach can lead to more serious violence and victims will refrain from reporting abuse and seeking help in the future.”

The report “The Right of Access to Justice for Abused Women in the Republic of Armenia” states that domestic violence cases are unique in that the abuse has usually lasted for years and that it sometimes continues even during court hearings, especially when the defendant is still free.

According to the report, it is common for women who are survivors of domestic abuse to withdraw their lawsuit. Although legislation allows the investigation of a case to continue even in the absence of a claim, in most cases law enforcement agencies stop preparing materials or halt the preliminary investigation.

Women who have been interviewed by investigators state that the detectives in the police department are insensitive. For example, women are often asked “Why did you leave and then go back to him?”or “Both of you need to get yourselves together, or I’ll contact the Trusteeship and Custodianship Commission and I will take your child from you.” or “You’re testifying against your own husband.” The police’s approach has left women feeling helpless instead of protected.

“All the abused women participating in interviews stated that the police did not explain their rights, did not explain the different types of domestic abuse, and were not willing to hear about ongoing violence,” the report states.

The report “Challenges and Gaps in the Response to Domestic Violence in the Republic of Armenia” states: “There was a case when the abused person arrived at the police station with a social worker and a lawyer and she was addressed as ‘the wife of police officer X.’ Meanwhile, the police officer who had committed the abuse was drinking coffee and making jokes with his colleagues.”

The Women’s Support Center has encountered cases where the perpetrator was a police officer, and his colleagues not only showed a biased approach to the person subjected to violence but even threatened her.

Anna, 37, whose name has been changed, is faced with a similar problem. She separated from her husband after years of abuse but is currently denied access to her children because her husband and his family refuse them contact.

“My ex-husband works in the military and he has repeatedly threatened that if I come near our children, I will be found killed in the street,” says Anna. She also says that despite missing her children, at least now she is not subjected to abuse, that she has found herself, is working, and trying to do everything she can to have her children returned to her.

Crime and Punishment

In Armenia, the first mechanisms for preventing domestic violence and protecting survivors of abuse were introduced in 2017 after a long struggle with the Law “On Prevention of Domestic Violence in the Family, Protection of Victims of Violence in the Family, and Restoration of Harmony in the Family.” However, experts in the field have repeatedly spoken about flaws in this law. In 2022, members of the ruling Civil Contract Faction of the National Assembly Zaruhi Batoyan, Tsovinar Vardanyan, and Sona Ghazaryan presented a package of legislative amendments to address the flaws in the law for public discussion. According to Batoyan, the changes are aimed at solving the problems that arose after the law’s adoption.

“With the package, we are trying to clarify the definitions related to domestic violence, for example, defining stalking as a crime,” explains Batoyan. “We also propose to limit the use of giving warnings for cases that refer to physical or sexual violence.” She notes that the aim of the new changes, however, is not so much to punish the abuser but to prevent cases of violence and to provide adequate support to the survivors of violence.

According to Hayk Mkrtchyan, Deputy Head of the Department of Prevention of Juvenile Crime and Family Violence of the Police and Head of the Department of Domestic Violence Prevention, the law had a positive effect.

“The number of registered cases of violence has increased,” says Mkrtchyan. “This means that people trust and turn to the police. Importantly, the increase in recidivism is not high. For example, during the first six months of 2022, we’ve had 296 cases where warnings were registered and 306 cases where urgent intervention was registered.”

Batoyan also emphasizes the fact that people are informed and want to protect their rights.

“This does not mean that the number of abuse cases has increased since the law was passed,” she says. “On the contrary, we have started to recognize violence and call it for what it is: not as just violence, but domestic violence.”

The Coalition to Stop Violence Against Women has sent its proposals for changes to the law. Zaruhi Hovhannisyan, a human rights defender responsible for the organization’s public relations, says that if the law enforcement system is not sensitive to women’s rights and is not knowledgeable of the law, then the protection of survivors of violence will not be effective either. Hovhannisyan also notes that criminalizing domestic violence is not included in the proposed package.

The package of amendments to the law also proposes the provision of free medical care to survivors of domestic violence, clarify and define the duties of police officers when moving an abused person to a shelter, and set higher fines if an officer purposefully fails to comply with a decision for urgent intervention or protection.

Innovative Support

Since 2020, state structures providing support centers and shelters for persons exposed to domestic violence began to operate in Yerevan and throughout Armenia’s regions.

In 2021, the Coalition to Stop Violence Against Women and the United Nations Children’s Fund presented an updated version of the SafeYOU online application which was created along with the Impact Innovation Institute LLC. The application creates a safe online environment for women and girls where they can get information, receive professional advice, and in cases of abuse, alert institutions that provide professional support. The app is free and includes information from a network of organizations that provide specialized services for preventing and protecting gender-based violence.

The app can be downloaded from Play Store or the App Store.

You can call the following hotlines for psychological, social and legal support:

In case of domestic violence:

(099) 887 808

(010) 54 28 28

In case of sexual violence:

(080) 001280

(077) 991280

Also see

When the Diagnosis Is an Infectious Disease, Discrimination Ensues

People living with infectious diseases such as HIV/AIDS often face discrimination not only by society, but by medical staff. This causes challenges with the care these patients desperately need.

Read moreUnwanted: Why Is Abortion Still the Main Form of Family Planning in Armenia?

Abortion continues to be the primary measure of fertility regulation in Armenia and despite efforts to decrease the number of sex-selective abortions, these issues remain prevalent in the country. Sona Martirosyan explains.

Read more“Let Me Take Your Pain”: Palliative Care in Armenia

The Palliative Care Center steps in when conventional medicine stops working and the body does not respond to therapy. Gayane Mkrtchyan looks at the state of palliative care in Armenia, its challenges and prospects.

Read moreUnderstanding Postpartum Depression

Having a baby is the most joyous time in a woman’s life. The experience triggers powerful emotions and in some cases, can lead to postpartum depression. Gohar Abrahamyan provides valuable insights through her own personal journey.

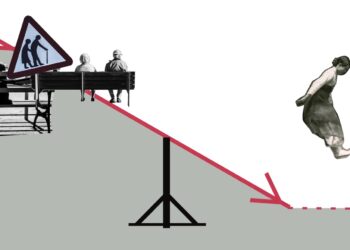

Read moreArmenia in Demographic Crisis

Recent data warns of a demographic crisis in Armenia. In a country with a high rate of aging, programs are being implemented to boost birth rates. But are they effective?

Read moreCatching Cancer in Time

The case for early detection of cancer and shifting cultural attitudes toward seeking medical treatment in Armenia.

Read moreObstetric Violence: Hidden in Silence

Many women are subjected to obstetric violence, which not only violates their right to receive dignified and respectful health care but can also seriously threaten their life and health.

Read moreSocial Responsibility and the Limits of Social Norms

Is it acceptable to throw your cigarette butt on the street? Is it understandable to be a draft dodger? Mikayel Yalanuzyan looks at how social responsibility is understood in Armenia.

Read moreCombating Child Sexual Abuse

Although norms prohibiting violence against, and sexual exploitation of, children have been enshrined in international and domestic legal mechanisms, violence against children remains one of the most serious challenges in the modern world.

Read more