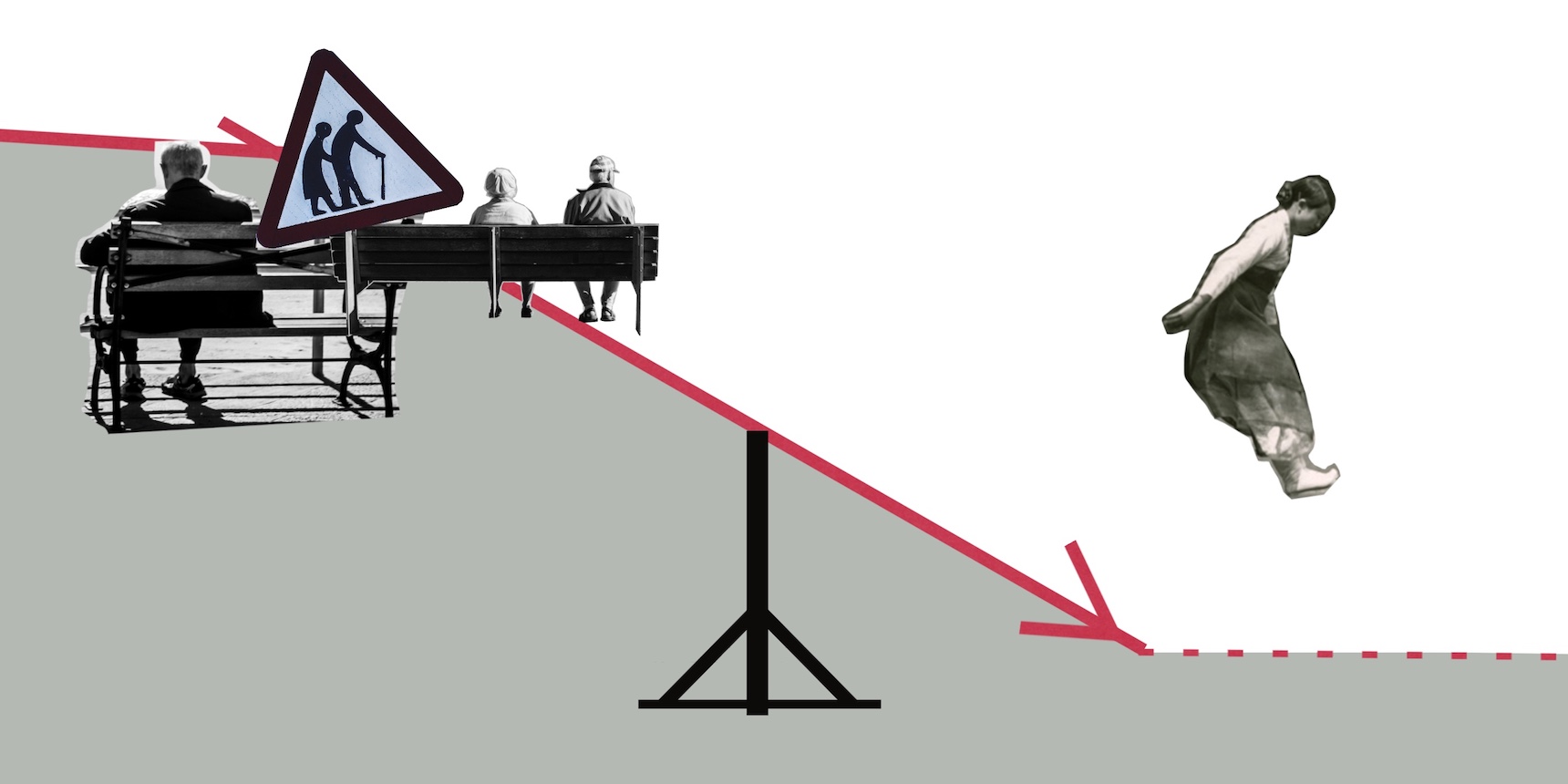

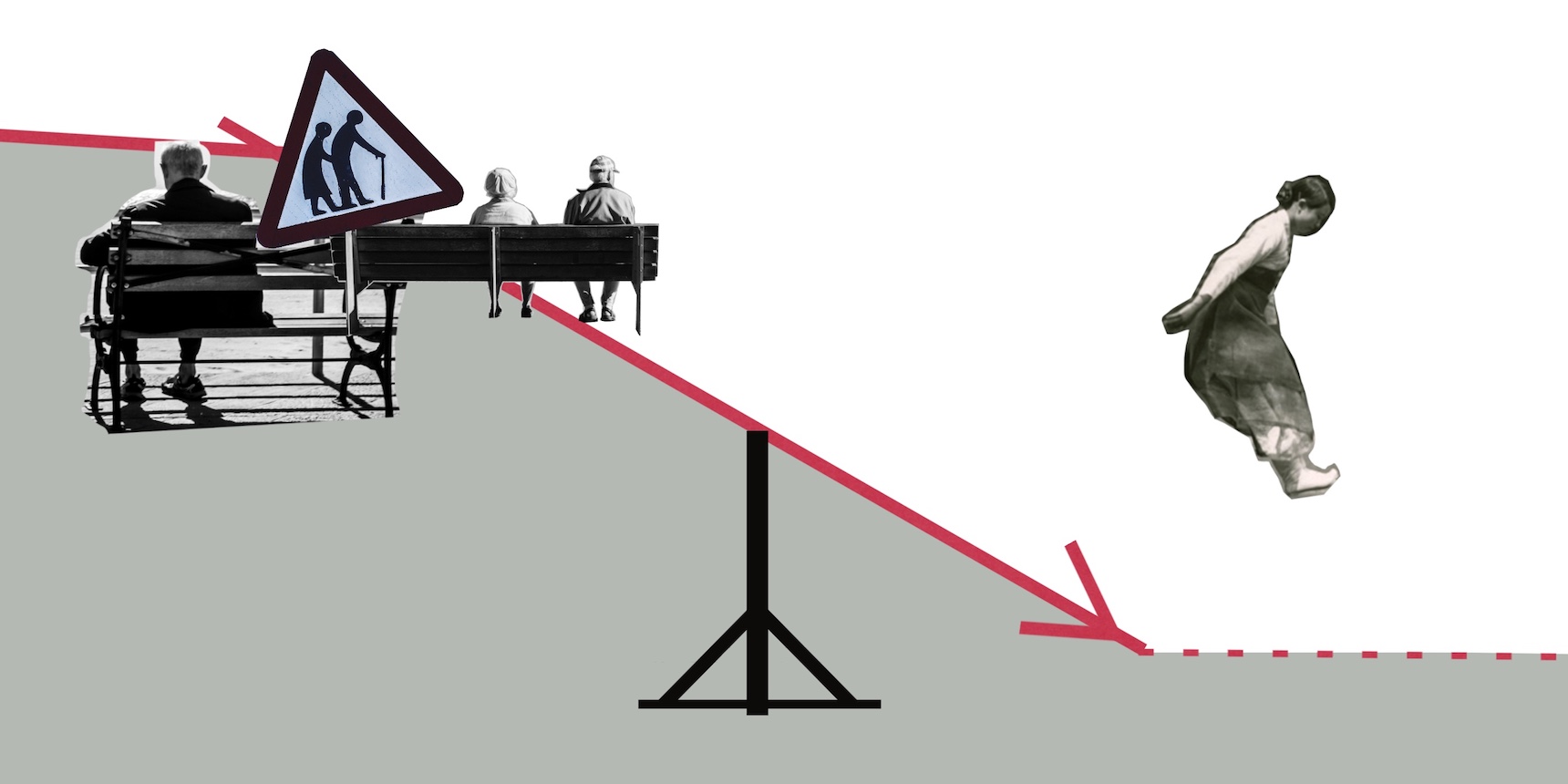

Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

We Live in a Region Where We Cannot Decrease in Numbers

After having her second child, Ani Nahapetyan, a teacher, returned to work right after her maternity leave ended in the hopes of easing her family’s financial burdens. She postponed future plans to have another child.

“First, we have a mortgage, and, second, life has become difficult, everything has become more expensive, it’s become difficult to live,” says Nahapetyan, 32. “Children are a huge responsibility. If you have them, you have to be able to take care of their every need. Meanwhile, today in Armenia this is not that easy. And I don’t blame those who are content with having only one child.” Nahapetyan says that they have many acquaintances who want to have three or more children, however, financial fears constrain this wish.

Although Armenia’s government has been carrying out programs to increase the birth rate and support young families and families with children, Nahapetyan believes that money alone cannot serve as a motivating factor.

“The first five years are the easiest. The difficulties start in the following years,” Nahapetyan explains. “Other types of incentives and conditions are necessary for parents, such as medical insurance. The health care system in Armenia is quite expensive. Only state employees have privileges and access to social benefits. But what about those parents who don’t work for the state?”

There are serious concerns that Armenia is on the path to depopulation and in order to mitigate this and increase the birth rate, Armenia’s government increased the one-time benefit given to families for having a child. That number increased six-fold on July 1, 2020 from 50,000 AMD to 300,000 AMD. The benefit given for a second child doubled from 150,000 AMD to 300,000 AMD. The monthly amount given to parents for the care of their child until the age of two has significantly increased – from 18,000 AMD to 26,500 AMD. Back in 2014, a government decision was adopted to allocate 1,000,000 AMD for a third and fourth child and 1,500,000 AMD for the fifth and every subsequent child. At the beginning of 2022, a new program was announced to encourage families to have a third child or more. For this, a monthly payment of 50,000 AMD is provided to families for their third or subsequent child born after January 1, 2022 until the child turns six years old.

Moreover, the government decision on “Approving State Housing Support Programs for Families with Children for 2020-2023” was passed on May 14, 2020 to support families.

During a June 10, 2022, session of the Council on Improving the Demographic Situation, led by Deputy Prime Minister Hambardzum Matevosyan, strategy development plans were presented to ensure a stable increase of the birth rate in the coming years and, in the long term, create preconditions to ensure a stable increase in the country’s population.

During the session it was announced that the budget for programs aimed at improving Armenia’s birth rate rose from approximately 14.5 billion AMD in 2019, to 31.4 billion AMD in 2022.

However, according to demographer Artak Markosyan, an associate member at the Armenian Institute of International and Security Affairs (AIISA), while the birth rate increased in the 2000s, it did so without any systematic policy to support it.

“In those years, the birth rate was growing, however, we didn’t take advantage of it,” says Markosyan. “This is because there was no incentive policy.” He recalls that when former President Robert Kocharyan was in power, the monthly stipend for child care was 2,000 AMD. “Back then, the birthrate was high because those born in the 1980s were reaching marriage age,” explains Markosyan. “Until 2008, the one-time sum per child was 35,000 AMD. I’m not even mentioning those residing in villages––unemployed mothers received no money, but today they receive 26,500 AMD monthly.”

In evaluating the effectiveness of the state’s support programs, Markosyan says that after 2014, the 1 million AMD and 1.5 million AMD monetary allocations have contributed to families having a third child.

“Currently, it is because of this that we are staying afloat, that there is no decline, because since 2012 the number of first child births is declining,” says Markosyan. “The decline will continue because the number of marriages will decline.” He emphasizes that soon those born in the 1990s will reach childbearing age. They are already relatively less in number and that is a fact that cannot change. “There is a fixed number of those getting married, we can’t add or reduce it. We can only influence those people to have lots of children,” he explains. “The number of births has not increased since 2014; it has decreased across the board except for numbers of third children being born, which have increased.”

According to Markosyan, in 2020, a 5% increase of births was registered compared to the previous year: the number of births of a third child or more compensated for the number of first borns.

In 2021, 36,585 children were born in Armenia. According to Markosyan, if the state is able to maintain 36,000 births annually until 2030, then this can be considered a great achievement.

“Efforts need to be taken to maintain this as well. If not, our numbers will decrease,” Markosyan explains. “One such policy could be legislation to support families with three or more children. This has to be the foundation for a population policy. Demographic policy has the following logic: you can improve the situation through financial tools, however, it is necessary to present alternatives to people that will help them decide whether they want to have more children or not.” Those alternatives or suggestions could include assistance with education or health insurance for parents, he says.

Markosyan notes that although international experience should be taken into account, that experience must be contextualized for Armenia considering its resources.

“States spend a great amount of money on this issue,” he explains. “A child born today is not for the present; demography is not for the present, it is based on the past and the future.” Markosyan emphasizes that this science has no “present”: it works based on data from 20-30 years ago for 20-30 years down the line. “If we were in Europe, I would say that everything is normal, a birth rate of 1.7 is great,” he says, adding that with declining numbers, the threat of depopulation in Armenia is very real. “We live in a region where we don’t have the right to decrease in numbers. Today, our fertility rate is below two children per family. We have to at least strive toward this. If we can ensure a fertility rate of two per woman, there would be an increase in the number of births. This would lead to a stabilization of the situation.”

Deaths Are Exceeding Births: Armenia on the Path to Depopulation

According to data from the Statistical Committee of Armenia, in the past several years, Armenia’s population is declining.

The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) carries out population projections every two years. Analyzing this data, Anna Hovhannisyan, Program Coordinator of the UNFPA’s Population and Development project, states that the number of births decreased in January and February 2022, while the number of deaths increased.

“In February 2022, 2,476 births* were registered and 3,241 deaths,” Hovhannisyan says. “However, professional circles believe that by the end of the year, this picture will change. Of course, we still have time before the end of the year, but if this trend continues we will find ourselves in a situation of depopulation.”

Demographer Ruben Yeganyan states that this situation was expected because already last year, depopulation was registered in Lori marz.

“For the first time since the Soviet era, we had a decrease in population,” says Yeganyan. “The majority of Armenia’s regions are experiencing similar numbers as well. The pandemic and the war sped up the process.”

According to Artak Markosyan, there is another problem: for three years Armenia registered a high number of deaths.

“Even in this quarter, when the number of deaths from COVID-19 has decreased, the percentage of deaths from other diseases remains high,” explains Markosyan. “As a professional, I am more interested in deaths than in births.” He says that in the first quarter, natural growth was less than 609 people; in the previous year for the same quarter, it was 240.

According to Markosyan, even though the issue is serious, it will only be possible to get a complete picture at the end of the year. “Usually the number of births is higher at the end of the year than at the beginning. The numbers are still going to change,” he says.

In Armenia in 2021, 36,585 children were born and 34,658 people died; births exceeded deaths by 1,927. In 2020, births exceeded deaths by only 183. Meanwhile, in 2019, births exceeded deaths by 9,855. Thus, the number of deaths in 2021, compared to previous years, decreased by 1,500. Compared to 2019, this is a 35% increase. The last year that deaths surpassed births was in 1988 when the Spitak earthquake claimed more than 25,000 lives. During the 2020 Artsakh War, Armenia had nearly 4,000 combat related deaths. In 2021, 5,450 people died due to COVID-19 compared to the 3,540 that died in 2020.

“The deterioration of the socio-economic situation in Armenia is also a serious problem. We’re not taking that into consideration: inflation, the devaluation of the Armenian dram, all of this has its effects,” explains Markosyan. “Prices are rising, but in the meantime, people’s income is not increasing. All of this cannot but have a specific impact on demographic processes.”

Armenia Is an Aging Country

Armenia’s aging rate has demographers concerned. According to the UN, if the percentage of the elderly is more than 7% of the population, then that country is considered an aging country. Armenia’s elderly is double that.

“In Armenia, the percentage of the elderly is about 14% which means that Armenia is a country with an aging population,” explains Anna Hovhannisyan. “Such phenomena are typical to all those countries where the aggregated birth ratio is low and has a tendency to decrease.”

According to demographic projections, this indicator will reach 22-24% in 2050. This means that one in five people will be elderly, or retired.

“I don’t want to observe this as a strictly negative phenomenon,” says Hovhannisyan. “The elderly should be seen not as a burden but as an opportunity. It’s like this all around the world because people have started to live longer. We have to use this opportunity, we have to take advantage of their resources and potential.”

Ruben Yeganyan agrees, especially with regards to those who retire but continue to remain active and creative. However, he acknowledges that the elderly will reach an age when they will become dependent on society in order to survive. “In essence, we’re not aging, we are an already aged country. Even based on UN standards, we’re already an aged country. Of course, there are older countries than ours. For example, it’s difficult to compare ourselves to developed European countries that have already passed the 25% threshold. We still have a long way to go. But these countries have accumulated experience and economic opportunities.”

Artak Markosyan also states that Armenia is already an aged country. He brings the example of Japan, considered a “super-aged” society with 28.7% of the population 65 or older.

“But they have been able to keep those at retirement age in the labor market with incentives, they’ve created special mechanisms,” he explains. “We don’t have such programs, unfortunately, because employment rates are lagging. Our programs don’t correspond to the reality we have at this time. This is a serious shortcoming. We have to start thinking about this today because our life spans are going to get longer. People aged 60 and older are still able to work. We just have to understand how and where to use these people and it’s necessary to have a clear policy.”

Numbers of Young People and Marriages Decreasing While Age of Motherhood Is Increasing

During the last decade, the number of youth (0-18 years of age) in Armenia decreased by 240,000. Anna Hovhannisyan says this indicator is very worrisome and notes that people in that age group are about to start working. According to the UNFPA’s biennial population forecast, the youth unemployment rate in Armenia is high: 34.5% among young women, and about 27% among young men.

In 2020, the lowest number of marriages was registered in Armenia, approximately 12,000. In 2021, there were 17,000 marriages, a 40% increase. In demographics this is called “postponed marriages,” when due to special circumstances, in this case due to the pandemic and the war, marriages were postponed. In 2021, the number of divorces also increased by 33%.

“The average age for motherhood increased from 24 to 29 in the last decade,” says Hovhannisyan. “The later a person initiates the reproductive process, the less time they have to realize their reproductive potential. According to our predictions, in 2050 the average age for first-time mothers will become 30.”

Artak Markosyan also states that if marriages weren’t postponed in 2020, it’s quite possible that a decrease would have been registered in 2021.

“We are now entering a declining phase of marriages. This phase will pass, but in several years, we’ll see a serious drop in the number of births,” he explains. “At first, the number of marriages will decline, then three to four years later this will affect the number of births. In the first quarter of this year, this number dropped because, based on certain calculations, the generation born in the second half of the 1990s are entering marriageable age. We are on that dropping curve.”

Do Births Increase After Wars and Natural Disasters?

Ruben Yeganyan states that after war and natural disasters an increase in births is called compensatory birth rate, but is not inevitable in all cases.

“This was especially true after the 1988 earthquake when we had 84,000 births in 1990,” Yeganyan says. “The natural disaster that took place affected all genders and age groups; families were split and lost children, and new families were formed by those who had lost loved ones and wanted to reconstitute what they had lost. But what took place with us in the past two years will not likely lead to something similar.” He explains that the war losses were mainly those who had reached reproductive age but who had not yet begun to get married or have children. Meanwhile, their parents had already passed the age of the so-called compensatory opportunity. “I don’t think we will have a similar situation as after the earthquake,” he states.

Evaluating Armenia’s demographic situation overall, Artak Markosyan states that the country has been in this crisis for thirty years and that the crisis had an artificial component. After 1991, population growth was constantly artificially interrupted because of situations which did not occur naturally.

“The number of births was going to decrease after 1986 and independence had nothing to do with it; the birth rate was going to drop and that was a natural process,” he says. “We had an increase in births in the 1990s but there are several illusive factors here. In 1988 the earthquake happened. Before the earthquake, 81,191 children were born in 1986. That number dropped to 74,000 in 1988 which was a natural process because the generation born during the second half of the 1960s entered marriageable age. After the earthquake a recovery phase took place in 1989, 1990 and 1991 and that increase was not natural because people were trying to restore the losses of their families.”

Markosyan says that in 1992, 70,000 children were born in Armenia. Ten years later, in 2002, that number dropped to 32,380, a 60% decrease. “This is connected to Armenia’s socio-economic conditions and ensuing emigration, war, and the deterioration of the security environment,” he says.

*Correction: An earlier version of this article said that 2476 births were registered during the first two months of 2022. It should have read for the month of February.

Also read

Ill and in Anticipation of a Miracle in Germany, Part 1

Refugees have been living in a Düsseldorf's shelter for years, receiving treatment and waiting to either fully recover or be deported. In this series of articles, Armenians reveal how they arrived in Germany in anticipation of a miracle.

Read more200 Years of Armenia As a Refuge for Russian Emigres

While the recent wave of Russians moving to Armenia following the invasion of Ukraine has been surprising to some, it’s worth pointing out that Yerevan has hosted successions of Russian emigre communities for quite a long time now.

Read moreCatching Cancer in Time

The case for early detection of cancer and shifting cultural attitudes toward seeking medical treatment in Armenia.

Read moreObstetric Violence: Hidden in Silence

Many women are subjected to obstetric violence, which not only violates their right to receive dignified and respectful health care but can also seriously threaten their life and health.

Read moreKeeping Fireplaces Lit on the Syunik Border

Social assistance to Syunik’s border villages includes subsidizing natural gas bills, but that’s no use to residents when the pipes don’t reach their homes. They don’t want to leave, but are enduring unprecedented hardship.

Read moreArmenia’s Fight Against Human Trafficking

Human trafficking is among the world's fastest-growing criminal enterprises and is estimated to be a $150 billion-a-year global industry. Since 2002, Armenia’s government has demonstrated increasing efforts to combat trafficking.

Read moreWhen the “Urban” Meets the “Political”

Following the events at Yerevan City Hall and now-former-Mayor Hayk Marutyan, the complicated relationship between the “urban” and the “political” in post-revolutionary contexts comes to light.

Read moreSocial Responsibility and the Limits of Social Norms

Is it acceptable to throw your cigarette butt on the street? Is it understandable to be a draft dodger? Mikayel Yalanuzyan looks at how social responsibility is understood in Armenia.

Read moreWho Benefits From Comfortable Workplace Environments for Mothers and Babies?

Having a designated nursing room at the workplace and flexible working conditions help working mothers to continue breastfeeding after returning to work, keeping the emotional bond between mother and baby uninterrupted․

Read more

The article claims that during the first two months of 2022, 2476 births were registered. This makes on average 42 registered births per day which is well below the daily registered figures of well over 100 per day seen on state television. I wonder if you could shed some light on this discrepancy.

Perhaps the Diaspora can establish a fund to reward Armenian families to have more children.

Good idea!

An important issue that needs to be tackled sooner rather than later.

@Daron, the issue isn’t just one of money. The Armenian government is already giving large one-time payments. The issue is long-term support. Some of that is financial, e.g. paying for healthcare, but a lot of it comes to developing good policies. For example, in Germany, parents can take their children on the train for free up to the age of 14.