Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

Crossing borders legally and illegally, overcoming ordeals to get to Europe, and applying for refugee status just to be given the opportunity to receive life saving medical care – this is what Armenians with terminal illnesses often do to try to survive and prolong their life.

In the Düsseldorf refugee shelter, there are Armenians who have been undergoing treatment for years, awaiting to either fully recover or be deported. Days, months and years pass like this.

They are provided with medical care and the basic amenities at the shelter: a bed, medication, and equipment for physiotherapy. Most of those staying here applied for refugee status anywhere from three to seven years earlier. There are people who still do not have a temporary residence permit and are at risk of being deported at any given time.

Alone and Ill: From One Corner of the Map to the Other

“I went to Ukraine from Yerevan, then to the Czech Republic, and from there to Germany,” says Mane, when recounting her journey to find treatment. She was willing to share her story, but did not want to be identified by her real name.

Due to the lack of medical specialization and the high price for medication in Armenia, doctors advised her to go to Germany or Israel for treatment. Mane, however, did not have the money to cover the cost of treatment.

“I had lived, studied and worked in Artashat for 26 years. I rarely needed to go to Yerevan, and if I ever did, my brother accompanied me. Then suddenly one day they told me, ‘You are sick. You have to go to Germany all by yourself,’” Mane recalls, reliving the emotions she experienced four years ago. “There was a lot of panic and sobbing involved, as I didn’t want to go. Facing the big world alone, with just a suitcase in your hand, you go to save your life and get treatment.”

Filing an application for asylum was a very difficult moment, Mane explains. “They told me to go and say (asylum in German) and that’s it. I was stressed out for a few days, thinking what if they ask me something else? I do not know the language. What will I answer? What if they send me back? I have traveled so far, spent so much money. There were personnel in uniform at that refugee reception point whom I approached and fearfully said asyl. They said ‘OK’ and took me inside,” she says.

Mane, who had been to a camp as a school girl, had a rough idea of what to expect; much like camp, the building was located in a forest, with a canteen and a doctor. Everything was structured according to a schedule, with strict rules and regulations.

Later they transferred her to the refugee shelter.

“I got there and thought ‘this is the end of the world…I am returning to Armenia,’” says Mane, remembering how dirty the rooms were and how she had to adapt to the living conditions.

However this was just the beginning.

“Then letters started coming in, urging me to leave the country. They did not believe that I was seriously ill, until the letter from Armenia’s Minister of Health came, stating that my heart condition could not be treated in Armenia. I also had seizures and that was when they realized I was not lying and they saved my life,” says Mane, noting that a lot of money was spent on her treatment by the German government, money that she would not have been able to able to secure in Armenia, “What kind of job do you have to have in Armenia to make 5,000 euro a month to buy two drugs, not counting all the tests that are free? I have been here for exactly four years,” Mane says. “How can I not be grateful to the German government for saving my life?”

Although she currently holds a temporary residence permit for three years and the risk of deportation is small, she faces other challenges: she has to learn German and find a job, otherwise she will face deportation.

It is a bit challenging for someone with health problems to work. According to Mane’s doctors, she can only work three to four hours a day.

“I want to work as a hairdresser, but the work schedule is eight hours,” Mane says. “I will probably study to become a manicurist just so I can begin working.”

Mane notes that the notion of a prosperous life in Germany is sometimes exaggerated.

“When I am asked for advice on whether or not someone should come to Germany, I say if you have the possibility, do not sell your house, do not take out loans, just come and try it. God willing, everything will go well, but if not, do not lose what you have back home. Nobody knows for sure whether they can stay here or not. It’s a shame to leave all that you have, come here and then go back again,” Mane says, adding that often, Armenians misrepresent their lifestyle in Germany. While you are provided with medical treatment and money for living, it is often barely sufficient for food. “This country is not obligated to do everything for you either. But the most difficult part is the longing for family and friends, overcoming difficulties all alone is really not easy.”

Humanitarian Aid in Numbers and Facts

The 1951 United Nations Convention on the status of refugees, defines a refugee as “someone who is unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion.”

Health issues cannot be grounds on which to grant refugee status under the Geneva Convention, but for centuries, the medical component of migration has been a cause for concern. Since countries accept their responsibility, and conditioned on this humanitarian factor, the EU—with its well-developed healthcare system—helps refugees who have different problems.

Ani Smith-Dagesyan, a member of the German Pan-Armenian Council board, has been living in Düsseldorf since she was 18, initially on a student visa and then for work. She knows a lot about how Armenians come to Germany and the problems they face.

According to Smith-Dagesyan, before the 2020 Artsakh War, the majority of Armenian migrants to Germany were cancer patients and those diagnosed with kidney failure. After the war, however, the number of people with combat-related wounds that need rehabilitation and prosthetics has increased.

“We have three different groups of people who come to Germany: people who come and receive treatment financed entirely by themselves, or through fundraisers organized in advance, [such as through] social networks or by applying to various foundations; people who think they can cover the expenses, but after a while are forced to apply for refugee status to continue their treatment; and those who are ill, and come and immediately apply for refugee status to receive humanitarian medical care,” says Smith-Dagesyan.

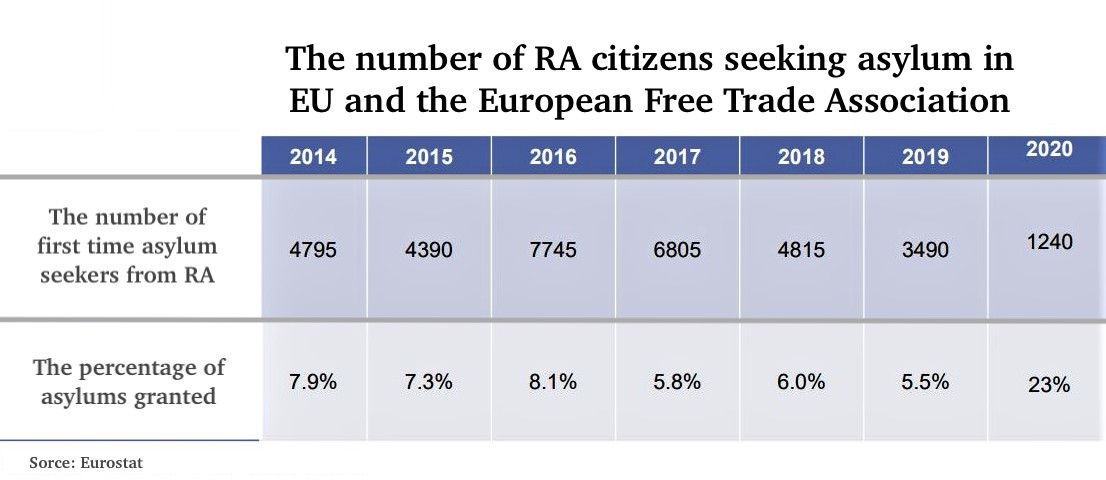

According to Eurostat statistics, from 2014 to 2020, the largest number of Armenian citizens seeking asylum in the European Union and the European Free Trade Association was in 2016 with 7745 people, and the lowest was in 2020 with 1240 people.

Armen Ghazaryan, head of Armenia’s Migration Service notes that in the early 2000s the number of Armenian asylum seekers to the EU reached 8000 annually, but in recent years that number has declined to 2000-3000, and continues to fall year after year. This is due to a number of reasons. First, the migration policy of the EU member states has been tightened, especially after the 2015-16 migration crisis but also Armenia has been recognized as a safe country, and most Armenian citizens do not meet the requirements of several EU countries and of the Geneva Convention for obtaining refugee status.

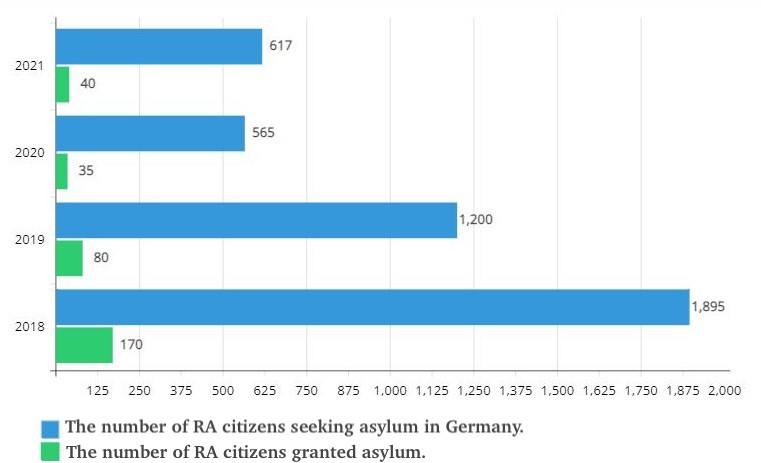

If we look at the data provided by the German Federal Office for Migrants and Refugees, most applications from Armenian citizens were rejected.

Referring to recent statistics on rejections and deportations, Ani Smith-Dagesyan notes that in the past, the German Migration Service was overloaded and understaffed with only about 3,000 employees Today, however, the number of its personnel is triple that. Previously, reviewing the application of a refugee could take up to one to two years, during which time the applicant would receive all the necessary medical treatments. Currently, applicants receive an answer within three months. This is not enough time to receive medical treatment.

According to Smith-Dagesyan, there are also people who continue to take advantage of these applicants’ helplessness.

“They are mainly criminal organizations that work in all the South Caucasus countries, and have quite good relations with some embassies where officials are involved, receiving up to 20,000 euros to forge paperwork. This sum includes both obtaining a visa and transportation costs,” says Smith-Dagesyan, presenting her research done over the years. She adds that transportation is organized in different ways: legally, with a tourist visa after which they apply for refugee status once in Germany, illegally, crossing the border through Belarus or Turkey, or semi-legally through obtaining a visa from another European country, for example, Greece or Poland, and then coming to Germany.

The majority of people with medical conditions sell everything they own in Armenia just to be able to pay up to 20,000 euros to get to Germany with their family. But Germany does not always turn out to be the lifeline they were anticipating.

Elisabeth Petermichl, a social worker at the Berlin-based organization Xenion, says that their organization provides social and psychological support to asylum seekers and helps with translation.

“Refugees arrive here and do not receive help, because they have to prove that there is no treatment for that medical condition in their home country. Some migrants do not even have documents on the medical condition, while others bring pages of history relating to it. Our doctors are overburdened and do not have the time to quickly examine people or study those documents,” says Petermichel, explaining that all this is done on a voluntary basis, sometimes resulting in mistakes leading to appeals. However, if it is discovered that treatment of the medical condition is possible in the applicant’s country, the migrant is subject to deportation. The only exceptions are those who are on the brink of death and whose deportation can lead to loss of life.

Lies Lead to Deportation

“Many people lie; if in the past it was possible to deceive, to invent stories, today it is much more difficult to do so. Developing digital technologies also assist in discovering the lie and immediately deporting the perpetrator,” says Artak Kirakosyan, 44, a soloist at the Alexander Spendiaryan National Academic Opera and Ballet Theater. Kirakosyan has been receiving treatment in Germany for more than ten years and clearly remembers the day he arrived.

In May 2008, during a concert rehearsal for the 90th anniversary of Armenia’s independence at the Sardarapat Memorial, a sudden gust of wind toppled a 3.5 ton light fixture onto the stage where about 120 people were. While saving the lives of several schoolchildren, Kirakosyan was also seriously injured that day.

“The stage collapsed; it took the life of a small child and I found myself in this wheelchair. The weather and the poorly secured stage were the reason for this tragedy. I had an operation in Yerevan, but I needed a second one to be done in Germany,” Kirakosyan recalls. Fundraising managed to collect 21,000 out of 100,000 euros needed for his treatment; the rest was covered by Beirut-Armenian philanthropist, Harutyun Khachatryan.

Once in Germany, it became apparent that the operation done in Armenia was below par: there were bone fragments left in the spinal cord which would cause Kirakosyan constant pain․

“I asked the professor who had operated on me in Armenia why they hadn’t removed the bone fragments, he replied that the technologies they had were not adequate, and that he had done his best with what was available,” Kirakosyan explains. “I realized that if the equipment was unavailable, then we could not expect anything better. But then I developed a problem with my bladder, and was told by doctors in Yerevan that the only solution was to remove my bladder and recreate a new one using my intestine.”

Meanwhile, doctors in Germany came up with another solution; the bladder was not removed, instead, it is injected with Botox once every six months, as a result of which bladder contractions are restored. This treatment costs about 2000 euros. Kirakosyan mentions that his treatment expenses are not small: the wheelchair alone costs 2700 euros. There is also a special pillow on the wheelchair that allows him to sit for 24 hours without causing pressure ulcers. This pillow costs 700 euros. Add to that the cost of medicine and treatment which amount to 3000-5000 euros.

Kirakosyan says that every migrant moving to Europe must be prepared to go through hardships that can take years. There are people who, even without enduring those difficulties, return or are deported. There are people who have been in Germany for 15 years but still do not have a resident’s permit, and there are those who get that permit within five years of applying for it.

“I have been living here for over 10 years. I have all the necessary documents. During this time I was not idle; my family started working and paying taxes. I opened a cultural center, I teach children, I sing in different choirs; after all, you are in someone else’s house and you should not become a burden,” Kirakosyan says. “There are refugees that don’t do anything and sometimes even make demands. As the landlord, Germany has the right to ask ‘How long should I feed you, maintain you, tidy up your bed, and buy new clothes for you?’ That is why many migrants are told to leave.

“Yes, I am living in someone else’s home now. I wish my home had a similar health care system so that I could return.”

In Part II, the author presents stories of people who left for Germany for treatment, but in some cases found themselves empty-handed.

New on EVN Report

Politics

The Divergent International Approaches to Secessionist Inter-Ethnic Armed Conflicts

The global response to secessionist inter-ethnic conflicts is shaped by a number of factors, from the extent of the threat of ethnic cleansing, to possession and instrumentalization of energy sources and more. Sossi Tatikyan explains.

Read moreOpinion

Armenia: What Role to Play in an Increasingly Multipolar World?

Entering the post-Western world, the strategic debate is shifting from a world of alliances toward a world of partnerships. How will Armenia seize this shift of geopolitical tectonic plates?

Read moreCan the EU Influence Baku’s Behavior and What Does This Mean for Their Mediation Efforts?

Instead of making Yerevan step back every time there is a deadlock in the negotiation process, the mediators should instead develop the tools to pressure Baku. If they do not, another war in the South Caucasus is likely.

Read moreWhy Armenia Needs Realpolitik, Now

For over 30 years, there has been a constant refrain on the righteousness of Armenia’s national aims and precious little about the means towards those ends, and the feasibility of those chosen goals.

Read moreRaw & Unfiltered

Diaspora Models, Part 2: Portugal

In this article, journalist Tigran Yegavian looks at how Portugal has developed effective tools to strengthen its relationship with its diaspora and assert its international presence.

Read moreDiaspora Models, Part 1: Switzerland

As prosperous as Switzerland is, it has long been and remains a country of emigration, however, there are a number of structures available to Swiss communities abroad to ensure an optimal relationship with the country of origin.

Read moreEt cetera

When Futurists Met Their Coveted Future

Even though a collectivist and masculine culture is predominant in Armenia, it’s often challenged by smaller segments of the society that are proponents of individualistic values and/or advocate gender equality.

Read moreGlobal and Local Art Wars

The inclusion of two conflicting Armenian artists from different eras on a prestigious platform of global contemporary art reveals the need to fundamentally reconsider and rethink the Armenian artistic heritage of the recent past.

Read more