Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

“We failed the exam,” said a 19-year-old Armenian young man to an American DMV agent specializing in undocumented immigrants’ driving privileges. This youngster is one of a great number of undocumented immigrants who have illegally crossed the U.S. border from Mexico, a pathway that gained huge popularity among the Armenian young men especially during and after the 2020 Artsakh War. “We failed the exam,” I promptly interpreted by phone. The American was audibly confused: “Wait… Who we?” Though grammatically correct, my translation had, however, been culturally wrong. And I had to give him a short superficial linguistic-cultural explanation as to why this individual attributes his personal failure to some incalculable and indefinable crowd, of which he considers himself a member. In other words, besides just translating from Armenian to English I had to also translate the message from the language of collectivism to that of individualism.

The replacement of I with We is characteristic of societies that have a high index of collectivism, such as Armenia, where it occurs not only ideologically, but also linguistically. This unique linguistic phenomenon is widespread in Armenia, yet it has no name. Perhaps the very popular Armenian slogan from the recent past — Ours is different — is the fruit of this phenomenon. But how different is it? How unique is it in the global panorama?

Even though a collectivist and masculine culture is predominant in Armenia, it’s often challenged by smaller segments of the society that are proponents of individualistic values and/or advocate gender equality. One of the manifestations of these antagonistic cultures that coexist in Armenia was the performance titled “ՀուԶԱՆՔ ու ԶԱՆԳ” (HuZANK u ZANG, Excitement and Call). It was during this performance that the paths of the futurists, conservatives (the we-minded), and the liberals crossed.

One day futurists Azat Vshtuni, Gevorg Abov, and Kara Darvish are finally invited to the future they worshiped, to the faraway November 2, 2019.

Tempestuous sounds are calling

They are calling toward the distance

Tempestuous sounds are calling

To the stormy and fiery existence[1]

They were called toward the distant future by a group of contemporary artists – choreographer Hasmik Tangyan, poet Lilit Petrosyan, the CoChoLab students, and graphic designer Nvard Yerkanyan. HuZANK u ZANG was conceptualized in collaboration with Linda Nadji, a German visual and performance artist. The meeting place was the gigantic steel frame petals of the open air fountain right outside the Hanrapetutyan Hraparak (Republic Square) subway station in Yerevan, Armenia. “May our mighty steel hammer ring,”[2] [2] exclaims Azat Vshtuni’s excited book that had inspired the title of this public performance, “Steam, – soul, steel.[3] Poet-steel-genius.”[4]

Everything promised a successful get-together. Finally, the obscure pages of Armenian literature would be back in the limelight. The meeting of the futurist poets with their coveted future was going to take place via the poetry of the future.

The get-together, however, did not go smoothly. Two years later, choreographer Hasmik Tangyan was to write about the public performance the following on her Facebook page:

Dear HuZANK u ZANG

Last year this time, Narek, who was part of your performance/part of you was killed in the war, and I didn’t have the heart to celebrate this day. But, to me, November 2 is your day.

You know, after you, some people were fired, some withdrew into themselves due to stress, some refused to create, yet others found strength in you, some lost their self-identity, some bolstered their self-esteem at your expense, others wrote articles about you, and French magazines covered your story.

We fear remembering you. But do believe me we do not forget. You will be surprised but over the past two years there hasn’t been a single day when you were not mentioned. Some cannot stomach you, some can’t get you out of their heads, others are trampling on you. You are yet to be spoken to, to be studied, to be protected.

Happy Birthday!

What happened on the day of the performance and thereafter exposed many issues and antagonisms within Armenian society, which demand detailed anthropological and culturological research. I agree with Hasmik that there is still a lot to dig into. I started drafting this article almost immediately after the attempts to disrupt the performance and attack the performers on November 2, 2019. What troubled me was not just the acts of violence but the level of support they had among the general public against the background of sporadic, feeble expressions of condemnation. But very soon the essay came to a halt when I embarked on my search for tools that would allow me to see the bigger picture of why the society in Armenia where I hail from acts the way it does, what the underlying driving engines could be.

After almost a year-long stagnation, I revisited the essay during my trip to Armenia, at the end of September 2020. A paragraph or two later, the 2020 Artsakh War started. And in the first hours of the shocking bloodshed, I ran into a video of one of the protagonists of this essay calling to take arms on his way to the nearest recruiting station. Throughout the war, as I was waiting for my turn to be drafted, I occasionally checked his Facebook profile, cherishing a hope that he would survive. Only weeks after the ceasefire, it became known that he had been killed in action.

It took more than a year before I had the heart to restart working on this essay with the realization that prevention of future hate violence requires open discussion of the causes rooted in the moral fabric of our society. And yet these concerns were accompanied by a nagging question. Today, only a year and a half after the war, is our society capable of putting its biases aside and hold an unconstrained discussion on the roots of aggressive intolerance, harassment, hate speech, and threats of grave physical violence if they were initiated by someone who, a year later, displayed exceptional bravery by volunteering to fight on the deadliest of the frontlines of the 2020 Artsakh War on the very first day. Especially that he never returned, his death becoming his wife and daughter’s unhealable wound.

The issue needs to be addressed from the perspective of the cultural values we have developed as a society, their perception, and the mechanisms of ensuring adherence thereto. I will try to scratch the surface of the complex problem with the six-dimensional model of national values developed by Dutch social psychologist Geert Hofstede in 1980 (updated in 2005):

1- Individualism vs collectivism – the extent to which people feel independent, as opposed to being interdependent as members of larger wholes;

2- Power distance – the level of the society’s authoritarianism or, in other words, the extent to which the less powerful members of organizations and institutions (like the family, school, workplace) accept and expect that power is distributed unequally;

3- Masculinity vs femininity – the extent to which the use of force is endorsed socially;

4- Uncertainty avoidance – the degree to which the members of a society feel threatened by uncertain, ambiguous or unpredictable situations;

5- Long-term vs short-term orientation – the extent to which a society prefers to maintain time-honored traditions and norms while viewing societal change with suspicion;

6- Indulgence vs restraint – free gratification of basic and natural human drives related to enjoying life vs suppression of gratification of needs by means of strict social norms.

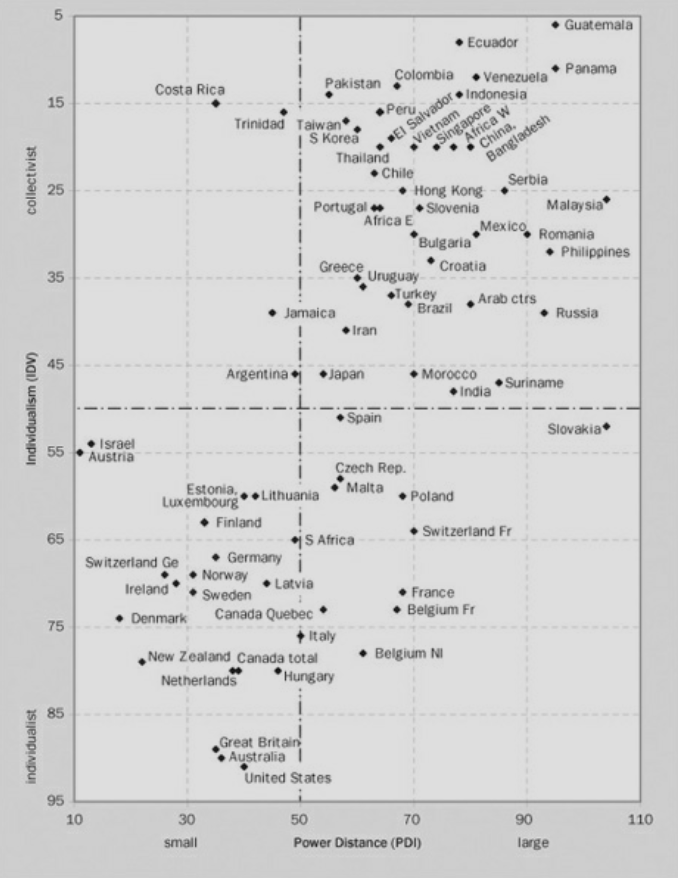

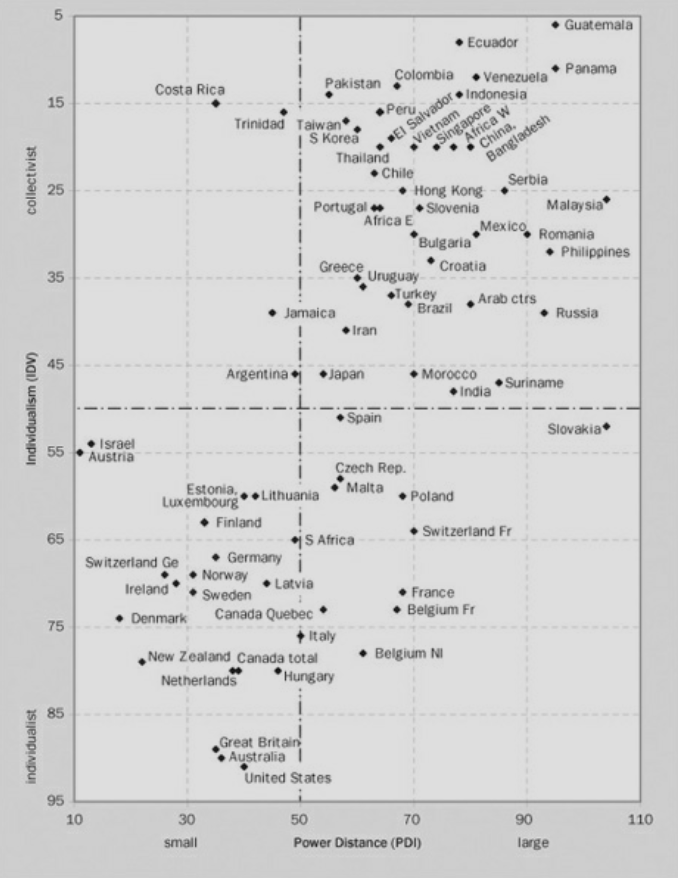

Figure 1. Power distance vs. Individualism in 50 countries

Through factor analysis, Hofstede has developed a framework of 100 points to measure cultural dimensions. Unfortunately, Armenia was not among the 50 countries selected for the study originally. However, an estimate was given by Hofstede Insight, a company that uses Hofstede’s 6-dimensional model to provide consultations for such multinational corporations and organizations, as Nike, Ikea, and UNDP, etc. According to Hofstede Insight, at 22 out of 100 the index of individualism in Armenia is, unsurprisingly, quite low, but very high on power distance (85) and uncertainty avoidance (88) (see fig. 1). Anyone born and raised in Armenia can attest, if not to the accuracy of the numbers, then at least to the general tendencies. For this essay, we will be focusing on the first four of the six dimensions, since they are more relevant to the issues at hand.

Figure 2. Hofstede Insight offers a tool to compare the indices of various countries on this page

Extended family, firm ties with blood relatives, a wide circle of friends who form a large support network; frequent, warm, and familiar communication; tradition of doing favors, reciprocal support; group interests are prioritized over individual ones; ensuring the well-being of all the other group members is vital. These characteristics are a furtive ground for establishing a society reflecting the views of anarcho-collectivism. And yet these anarchist dreams crumble the moment the society’s inequality comes forth with strict patriarchal hierarchy and gender inequality. When combined, these values may have the following manifestations: authoritarian familial and organizational hierarchy; high tendency to abuse power; importance of status symbols; perception of the woman’s role as support for a man to reach his goals; fear or skepticism toward the new; intolerance or aggression toward the unknown or ambiguous situations.

As for the status symbols, it is an important token of power or prestige in any society. However, in shame societies, like Armenia, it doesn’t always have to be backed by actual power. In this sense, the aforementioned young Armenian man who had failed the written test for driving is a typical example. One of the first things this undocumented, jobless, and financially vulnerable young immigrant had done after illegally crossing the U.S. border was to buy himself a vanity phone number. Ironically, Armenians have borrowed the English word “gold” to refer to these phone numbers, even though there is no such euphemism in America – phone numbers with repeating digits are referred to as vanity. Approximately every third undocumented Armenian immigrant I have interpreted for over the past year, had a vanity phone number.

HuZANK u ZANG was more than just performance art – it became a stage where the drama of these conflicting indices materialized. A day before the performance, a group of men approached the artists, disrupting their final rehearsal and demanding they not only stop rehearsing but cancel the show altogether. The men hadn’t liked the dancers’ unusual moves, which they declared to be “unwomanly”. All the participants of HuZANK u ZANG were young women.

Without introducing himself, one of them announced that whatever these young women were doing had nothing to do with art, was anti-national, anti-Christian, anti-state, and anti-human, filthy, and satanic without providing an argument to prove any of the accusations. At some point, it became clear that their hostile treatment of the girls was predetermined by their resentment toward the Ministry of Education, Science, Culture, and Sports, which had authorized and funded the performance. One of the reasons for the resentment, he emphasized, was the ministry’s decision to remove church history as a stand-alone subject from the school curriculum.

By addressing the artists with the patronizing erekhek (kids or guys), he assured the women they had been brainwashed; their brain had been replaced with bleach; they had been persuaded that it was OK for a woman to marry a woman, a donkey, a crocodile, etc. He reproached poet Lilit Petrosyan for the audacity of talking like men and using a vocabulary fit for men. The man also reminded all the young women that their primary mission was to give birth to children and raise them.

With his mansplaining, asserting his exclusive right to determine a woman’s place and role in the society, this man offered a masterclass portrayal of classic toxic masculinity. These men were upset by the failure of the women to comply with their roles. A man in such a society is expected to be assertive, tough, heroic, and ambitious, whereas women are supposed to be modest, submissive, caring, and their ambitions shall be confined to the goals set by men. Women shall not talk back to men. And homosexuality is a threat to the society, etc.

The masculine aspect of Armenian culture spills over to the language, its gender. Armenia has the reputation of one of the world’s rare gender-neutral languages. But is it? Linguistically – yes. Culturally – no. In reality, it is predominantly male – there have been attempts to establish a female third-person pronoun (né), but none for a male one.

The artists refused to give in to the pressure of the men who had disrupted their rehearsal. But that was just the tip of the iceberg. Despite the warnings and threats from the we-minded, the next day, the white-clothed performers appeared on top of the steel frame flower petals. The unrestrained meanderings of their body parts—as if invoking another futurist poet—recited:

And you

could you now

collect nectar

from the fountain of steel frame flowers?[5]

The performance had barely started when a large group of people in the audience made attempts to disrupt the show. One of them ripped the wires of the speakers before the eyes of indifferent policemen, after which poet Lilit Petrosyan had to yell out the intimate dialogue between her poetry and that of the futurists at the top of her lungs. It was, however, drowned out by a group of men chanting “Shame!” with megaphones. In spite of everything, the dancers willfully continued dancing as Lilit continued reciting.

The chanting of “shame” is a direct reference to one of the characteristics of collectivism: “Persons belonging to a group from which a member has infringed on the rules of society will feel ashamed, based on a sense of collective obligation.”[6] This obviously alludes to anthropologist Ruth Benedict’s proposal in 1934 to distinguish between shame and guilt societies. Within guilt society, the following question is fundamental: “Is my action just or unjust?” Law and punishment are important, the individual conscience is emphasized, and guilt is experienced whether or not others are aware of the act in question. Guilt is individual, whereas shame is social in nature. “Whether shame is felt depends on whether the infringement has become known by others.”[7] In a shame society, law and order are upheld through the indoctrination of shame and by the threat of ostracism (banishment, exile, isolation). In these kinds of societies an individual asks himself/herself: “What would they think? Will it be shameful if I did this?”

A zelyonka attack (a solution of brilliant green antiseptic dye) marked the peak of the attempts to abort the performance. A young man jumped into the heart of the performance and doused one of the dancers and then poet Lilit Petrosyan with the zelyonka. The policemen intervened and arrested him before he could splash the solution on the rest of the performers.

“There shall be no satanic manifestations in my country, as long as I’m alive,” yelled Narek Sargsyan, beside himself with rage in an increasingly scratchy voice as he was taken away from the scene.

In case of contact with the eyes, zelyonka can lead to corneal opacification and even bilateral blindness. It induces vomiting if swallowed and is toxic if ingested.

At 88 out of 100, the uncertainty avoidance is quite high in Armenia. The actions of the protestors that eventually garnered wide support both online and offline, back that evaluation to a certain extent. “The strong uncertainty-avoidance sentiment can be summarized by the credo of xenophobia: “What is different is dangerous.” The weak uncertainty-avoidance sentiment, on the contrary, is: “What is different is curious.”[8] Some of the characteristics of high uncertainty avoidance index are as follows: a) acceptance of familiar risks, fear of ambiguous situations and of unknown risks, b) aggression and emotions may at proper times and places be vented, c) high stress, high anxiety, higher neuroticism, d) hesitation toward new products and technologies, etc.[9]

And yet how could this small incident have caused some of the participants of the performance such serious and lasting psychological trauma as mentioned by Hasmik Tangyan in her retrospective letter?

The dominant conservative groups within Armenian society unleashed a wave of shaming and bullying after the incident was widely covered by the media. This is the toolset that shame society uses to ostracize its victim. The victim is someone who, having stemmed from a given society, inevitably asks himself/herself: “Would it be shameful if?” However, dares go against it by relying upon his/her own worldview, set of values and/or on the principle of “if it’s not prohibited by law then it’s allowed” characteristic of guilt societies.

The Ministry of Education was also lambasted, especially the members of the committee that had authorized this project with their signatures. The justifications by one of them, musician Gor Sujyan, particularly stood out. He swore in his Facebook posts and interviews, trying in every way to distance himself from the performance and its content in spite of his authorizing signature. At any rate, while Gor swore off with his excuses, Narek was stocking up on his supplies of zelyonka for the “future” (which Lilit recited repeatedly during the performance).

Narek Sargsyan was let go three hours after his arrest.

“So we got going and arrived. I’m telling you, I was treated so well that, as a result, I didn’t even consider calling my lawyer. These men are true Armenians,” said Sargsyan about what happened following his detention at the police station, during a press conference he organized two days later. He added that they didn’t even make him write an explanatory note. “That is to say, they treated me with respect, at a very professional level.”[10]

“In the individualist society, laws and rights are supposed to be the same for all members and to be applied indiscriminately to everybody (whether this standard is always met is another question). In the collectivist society, laws and rights may differ from one category of people to another—if not in theory, then in the way laws are administered—and this is not seen as wrong.”[11]

If we recall how easily the persons who blew up the DIY club out of homophobic views back in 2012 were released thanks to the Dashnak MPs paying the bail, then there’s nothing extraordinary about Narek Sargsyan’s quick release for a much milder wrongdoing, regardless of the fact that the former happened in pre-revolutionary and the latter in post-revolutionary Armenia. It’s a lot easier to change the undesirable people in power than the prevailing values that had brought them to power. Hofstede’s commentary on the effectiveness of revolutions in countries with high power distance index is as disheartening as it is sobering: “Most such revolutions fail even if they succeed, because the newly powerful people, after some time, repeat the behaviors of their predecessors, in which they are supported by the prevailing values regarding inequality.”[12] Though not ubiquitous and not as large-scale as under the previous authoritarian government, the few nepotist practices the media has uncovered in the past four years since the Armenian revolution back this statement.

In view of this grim picture, it no longer feels unfair that ten years later, just a few weeks ago, the European Court of Human Rights ordered the current Armenian government to pay Armine Oganezova, the owner of the DIY club, for the pre-revolutionary Armenia’s failure to protect her from homophobic abuse.

Couldn’t the impunity of the brothers who blew up the DIY have boosted the confidence of or even encourage those who harassed the performers of HuZANK u ZANG? During the same press conference, Narek Sargsyan not only showed no regret about his actions, but went even further. He seemed to have been enraged by the girls’ audacity to dismantle one of the tenets of a masculine society—“a girl must be obedient”—by refusing to give in to his demand that the performance be canceled the day before it was scheduled to take place. He expressed regret about not having gotten “bucketful of zelyonka.” He promised to seek even more brutal retribution for any similar occurrences.

Now let’s imagine the psychological state of the victims of his attack in this context, when their assailant is not only free, but, galvanized by impunity, publicly threatens to multiply and exacerbate the acts of harassment. What’s more worrying is when the society at large, with the exception of a few individuals and organizations dealing with human rights, doesn’t condemn or hold him accountable, doesn’t force him to at least substantiate the fairness of his actions with weighty arguments. He holds a press conference where he boasts about his actions with patchy sentences.

In response to a question why that performance should not have taken place, Narek chose to resort to ad populum fallacy: “Dear girls, or unidentified girl-like things that you are, just don’t do all that stuff, because society does not accept it.” His response is a suitable illustration of one of the features of collectivist societies as described by Hofstede – high-context communication, when little has to be said because most of the information is supposed to be known by persons involved, employing fewer words in communication with you-know-what-I-mean type of assumptions. This is contrasted by low-context communication characteristic of individualistic societies where everything should be specified and itemized explicitly, resulting in usage of greater number of words.

This dichotomy sheds light on the origin of the Armenian parasitic word “բան” (thing), the Joker of the Armenian vocabulary. In collectivist societies, the presumption of predetermined opinions about various phenomena and the assumption that all the members of the given society are familiar with them brings forth lingual sloth and verbal poverty in everyday communication. As a result, the daily vocabulary tends to shrink and many words are often replaced by the parasitic thing – “բան.” Sometimes this laziness reaches such levels of absurdity that a sentence becomes something like a solution of an equation with nothing but unknowns. There’s a popular self-critical joke about this in Armenia: «Բան անենք, բան ըլնի» (“Let’s do the thing to get the thing”).

When Narek was asked to prove what was Satanic about the performance, which had been declared to be the main reason behind his attack, he said: “The movements of the girls… kinda irregular words… like, the thing (բան), to me, remained confusing… which was explained by an expert (I’ll make a reference on my page), who doesn’t say 100% it was their intention or not, but he says these movements, these actions and words are mainly used by people who open portals.”

An entire creative group was publicly shamed, harassed, and racked because of this argument. One of the group’s leaders, Hasmik, designated Narek a participant of the performance. At first glance, it is bewildering, but when Narek, during his press conference, proudly refers to himself as “my rebellious Armenian soul,” everything falls into place. Rebellion is the very point where all three sides of the performance intersect. The targets of these three rebellions, however, are different, if not opposite. On the one side we have the advocates for rebellious denial of the old, the past – Azat Vshtuni and his futurist friends. On the other side is the rebellious Armenian soul that protects the old and the traditional – Narek Sargsyan and his fellow protestors. The third side is the creative group of HuZANK u ZANG that rebels against toxic masculinity and aspires for gender equality and treats the poetics of futurism with a mixture of admiration and sarcasm.

This antagonism probably dates back to the beginning of the 20th Century. While some imported elements of the Russian Gopnik culture into Armenia and had it crossbreed with the idiosyncrasies of the ethnic cultural traditions, people from another stratum of the society were doing their best to import the opposite thereof by localizing the Russian-Italian futurism and thus laying the foundations for a leftist culture. In that sense, the cultural clash that took place during HuZANK u ZANG could be viewed as a battle that had been brewing for decades between these antagonistic forces coexisting in Armenia, which is commonly regarded a cultural crossroad between the East and the West.

Let’s start with Azat Vshtuni. Azat Vshtuni rebels against traditional culture, independence of Armenia, and capitalism. He hails the Red Revolution and the establishment of Soviet Armenia.

In the song of yours,

rebellious denial of the old…

in the country of yours,

roar and joy right now.[13]

Would Azat find himself in his coveted future had Lilit and Hasmik stayed true to the letter of his commandment by making their song a ‘rebellious denial of the old,’ which is what futurist poetry inevitably is today? The futurists are here because the grounds for these rebellious girls’ denial of the old is not of chronological nature. Vshtuni’s soul rebels, for instance, in the following context:

Beethoven is but a weak shadow

against our gigantic songs of tomorrow.[14]

Or

Are you a Dante or

A Pushkin?

No, my comrade,

You are mightier.[15]

Or

Old Masis – an evil and trivial myth[16]

Are the girls in total agreement with these propositions? The creators of the performance are concerned with other ills, at least according to their public statements: “HuZANK u ZANG questions the public perception of women’s conduct, speech, and movements.”[17] The poetic component of the performance seems to target the triumphant march of capitalism and neoliberalism, while appearing to bemoan the failure or delay of the unification of the proletarians of all countries. As for much older issues, the poem tackles toxic elements of patriarchy and masculinity in contemporary Republic of Armenia, which has risen out of the ashes of “bold, titan-like, strong-willed” Soviet Armenia.

Had Narek Sargsyan chosen to read Vshtuni’s book in a quest to understand the theme of the performance, he would have bumped into the futurist’s malevolence about Mount Masis (the taller peak of Mount Ararat). It would still not justify the attack, but it would make his indignation understandable considering the undying symbolic significance of the sacred mountain for the Armenian identity. It would have been harmonious with his nationalist image and might even attract a larger number of supporters with stronger solidarity. However, instead of reading Vshtuni’s thin booklet, he preferred to resort to unsubstantiated and inarticulate accusations, such as this: “I qualify them directly as Satanists.” Thereafter employing incomprehensible syllogistic transitions, he ended up linking the girls’ actions to the popularization of “LGBT morality.”

When in “Pause, Passerby, Pause,” a documentary by Hovhannes Ishkhanyan, Hasmik Tangyan phoned Narek Sargsyan to offer a meeting, he replied at some point in the conversation, “Zelyonka can turn into petrol if I see that you guys are violating my national values. Tomorrow I don’t want my child to see a man in a skirt and ask: ‘Sorry, dad, but what is this?’ What am I going to explain to him? This is what you’re preparing the society for.”

And so it turns out that if this man does not know how to respond to his child’s curiosity about the peculiarities of people representing the LGBTQ community, they have no right to exist. Just because someone is reluctant to make a little effort to read an article or a book to be able to explain to a child in an accessible way about the biological particularities of homo sapiens or the wide-ranging diversity of their lifestyles, then they should be doused in zelyonka or petrol.

During the Occupy Wall Street movement in 2008, a photo became viral, where a cop was pepper-spraying the faces of any protestor he came across. Shortly after, the photo exploded into a viral meme. The cop was edited to pepper spray all kinds of cartoon characters, statues, characters in famous paintings from various historical periods.

When I heard Narek’s threats, I imagined a whole series of memes where the image of his zelyonka attack would be cut out of context and edited to splash the antiseptic brilliant green on various outstanding gay public figures. I imagined zelyonka being splashed on the world’s most quoted scholar, homosexual Michel Foucault; Oscar Wilde to prevent him from writing one of his masterpieces, De Profundis, while imprisoned because of his homosexuality. I imagined Sergey Paradjanov who had been imprisoned for similar reasons being blinded with zelyonka before he could make a single collage now displayed in Armenia’s most popular museum, before he would make The Legend of Suram Fortress or Ashugh Gharib. I imagined him splashing zelyonka onto Yeghishe Charents “lying on the round hips of a boy dressed in cowboy attire and sucking off his blazing cuddles.” Gay Pyotr Tchaikovsky’s ears should have probably been filled with so much zelyonka at birth so that he would never be able to write a single note, including The Nutcracker, which is among the Armenian children’s most beloved New Year performances.

Today, even though the situation is slowly getting better, still many in Armenia who openly embrace their non-traditional sexual orientation, especially transgender persons, are often subjected to discrimination, abuse, and humiliation, as testified in Nazik Armenakyan’s photobook The Stamp of Loneliness.

Narek Sargsyan eventually agrees to meet with Hasmik Tangyan at a café. During the conversation, both assure each other that they do love and care about Armenia and hold its cultural traditions dear. Symbolically, it was an important dialogue and manifestation of good will. But the devil is in the details. And there was, unfortunately, little substantive discussion to figure out those peculiarities of our national culture that set them apart, placing them in opposite camps. Even though Narek refused to apologize for any of his actions, he did nonetheless find strength to let bygones be bygones and give Hasmik a hug, when she gestured for it.

Lilit Petrosyan had refused to meet with Narek Sargsyan and had provided no particular substantiation about her decision. It has to be more than the fact that she was the direct physical target of the attack. Since the vocal layer of the performance failed due to the damaged wires of the speakers, I was able to familiarize myself with the poetry thanks to an audio file on her blog.

Was there Satanism? I don’t know. Being an atheist, I wouldn’t take it seriously anyway. However, I did not miss the following striking line: “Half-jokingly, half-seriously, half-God.” This line was the closest her poetry came to religious themes, then immediately left it behind.

The following lines from Vshtuni’s “We,” is quite impressively remade in Lilit Petrosyan’s contemporary presentation:

We are new! We, the young poets,

Our muse is the electricity, the steam![18]

Lilit Petrosyan managed to synthesize the futurist’s electric poetry with the currents of electronic music. At some point, however, the futurist’s excited words, charged with contagious optimism and strong belief in a bright future, are cut short by the poet of the future—our contemporary— not with pleasantries but withdrawal symptoms.

The following conclusion of one of the futurists (Abov or Kara Darvish), “The world has no borders now / It is new, infinite,”[19] is followed by “It’s all, It’s all, It’s all, It’s all / Withdrawal, withdrawal.”[20] Is this the voice of the future praised and longed for by the futurists? It sounds more like the despair, the withdrawal symptoms of the children of the progress propelled by their praised industrial boom of the 20th century. The children stuck in the everyday tedium, lost in the spaces between the scraps of the industrial revolution, with the aborted dreams of the working class.

It soon becomes obvious that Petrosyan has been enchanted by Vshtuni’s skillfully woven alliterations. And she, too, has succeeded in mesmerizing the listener with her own torrents of alliterations that put one in a trance. This is one of the successful attempts of translating Armenian poetry into electronic music. Among the successful texts are “you’re crazy like a beam of light” («խենթ ես դու մի լուսե») and “hot dog” («նուրբ երշիկ») by Gemafin Gasparyan (from his «Չկա՝ չկա», 2017), and Tigran Aleksanyan’s “Repetitive Technique” («Ռեպետիտիվ տեխնիկա», 2017). I am as excited about this poetic style as I am, certainly, biased owing to “House Sweet House,” (a poem from «Գրողի ծոցը» (Doomed to Spell), 2010).

The Armenian futurists use the word “genius” quite often. However, this honest genius roaming in the Armenian futurists’ texts, becomes a postmodern irony, a subject of mockery in Lilit’s post-futurist texts. Let’s compare:

And we, all of us as one!—

Poet-steel-genius…[21]

And Lilit Petrosyan’s text (the alliterations and puns are, unfortunately, mostly lost in this translation, where ‘seeking a way out’ in Armenian sounds like the word ‘genius’):

Have you become a derivative of a laying hen?

Are you an imaginary genius?

Or just seeking a way out?

Are you a genius, or just seeking a way out?

Are you eloquent?

Well then speechify

To find your way out[22]

From time to time, Lilit’s text deviates not only from the norms of the literary Armenian, but also penetrates the realm of the masculine thuggish argot with slang phrases, which is viewed as contemptible unwomanly behavior by the thuggish circles.

And from the distributor of miracles

Get me some green stuff.

I wonder what you give a shit about, bro.[23]

Afterward, Lilit unexpectedly switches to English. Surprisingly, irony and mockery now morph into an angry and frank rant swarming with furious foreign-language swearwords like “my fucking freedom,” “the fucking truth,” etc. She starts off touching on class conflict: “Only foolish, wretched profiteers are sitting now in their private luxurious rooms talking on behalf of real working class heroes. You know why? It’s cool to be a rebel when you are only a label.” What’s interesting is that by switching from Armenian to English, Petrosyan seems to also switch camps by shifting her target from the collectivist cultural elements to individualistic ones. In certain parts of her poetry, she mocks and cusses at privacy, a bastion of predominantly individualistic societies, in stark contrast with collectivist societies “where it is seen as normal and right that one’s in-group can at any time invade one’s private life.”[24] But why does Lilit Petrosyan switch from Armenian to English the moment she unleashes a torrent of swear words.

To better understand bilinguals’ physiological response to swearwords in their native (L1) and the second languages (L2), cognitive psychologist Cathy Caldwell-Harris and her colleagues, used lie-detector technologies in 2003 for investigating the skin conductance responses of Turkish-English bilinguals. They concluded: “Physiological reactions to taboo words presented auditorily in the L1 Turkish were found to be much stronger than their translation equivalents in the L2 English.”[25] It is due to this strength that bilinguals or multilinguals generally choose to swear in their native language to achieve the intended effect. This is corroborated by applied linguist Jean-Marc Dewaele’s study entitled “‘Christ fucking shit merde! Language preferences for swearing among maximally proficient multilinguals.”

But what Dewaele also revealed during his interviews explains Lilit’s seemingly counterintuitive choice: “A minority of participants went against this general trend, namely those of Asian and Arab origin who reported code-switching towards the foreign language, typically to express an emotion that was considered inappropriate in their L1 culture.”[26] As far as swear words are concerned, Armenia’s culture does impose constraints akin to those of its immediate neighbors. But unlike with men, women’s access to offensive vocabulary is significantly more restricted. Therefore the foreign language, which usually has lower emotional resonance, becomes the pathway for escaping social constraints.

Since foul language is generally perceived undesirable, inappropriate, or disgusting, few women tend to regard this one-sided stigmatization principally unfair. If anything they tend to believe they are just more well-mannered than men. And men do their utmost to make sure the women are not exposed to obscenities (like little children), and that is done as a sign of deep respect toward them.

Loading her poem with a grotesque amount of fucks appears to be Lilit’s way of protesting against such infantilization of women, against the society’s hypocrisy. At any rate, her protestation is somewhat cautious—by virtue of being in English.

Another reason for Lilit Petrosyan’s linguistic trip abroad is the way Violet Grigoryan, one of Armenia’s well-known poets, was treated for publishing the unprintable back in 2001. In the history of newly independent Armenia, she became the pioneer, among women, in crashing the taboo of using obscenities in literature, when she (or the speaker) wished she could be like Nayiri[27] and “shoot the motherfucker in the heart” in a poem. She had used the word gandon (a vulgarism borrowed from the Russian, which also means condom (quoting from memory)) in Grakan Tert, the official newspaper of the Writers’ Union. Predominantly female reporters subjected her to widespread harassment in the Armenian media. She was also castigated in university auditoriums including one at the Yerevan State Linguistic University after Bryusov, where the author of these lines heard her name for the first time from his pedagogy professor foaming at the mouth as he lambasted her waving the pertinent newspaper rolled into a cylinder. He let a few curious students read the segment. I was one of them. None of the girls asked to have a read.

Armenian society believes foul language ought to be not only age-restricted, but also gender-restricted. Tabooization of swear words solely for women is like an imposition of linguistic hijab. Often it just makes Armenian women import the Russian or English equivalents that have lower emotional resonance to use as stress relief during extreme frustration.

Even though I am not fond of cuss-ridden speech and don’t find this English-language fragment of Lilit Petrosyan’s fascinating poem very powerful, I think her temporary linguistic emigration points at a problem with the language, rather than poetry itself. I believe that the Armenian language should welcome any text with open arms, heart, and mind. The language should be hospitable regardless of gender, sexual orientation, or state of mind. Considering the diminishing number of its speakers, what the Armenian language needs for survival and endurance is not sanctification or purification, but the freedom of its male, female or gender fluid speakers to express as many hues of the human emotional palette as linguistically possible. It is with these considerations that I undertook the translation of the following excerpts from the English section:

|

Fuck privacy, man / Քունեմ գաղտնիությունը, արա Fuck your privacy / Գաղտնիությունդ քունեմ (կամ` փաթթած ունեմ) If the price is your fake democracy / Եթե դրա գինը կեղծ ժողովրդավարությունն ա Cause at the end of the day / Որտև վերջ ի վերջո Better be who you wanna be / Ավելի լավ ա լինել էն ինչ ուզում ես Than who is better to be / Քան էն ինչ ավելի լավ կլիներ լինել <…> Only foolish wretched profiteers are sitting now / Մենակ հիմար, թշվառ չարաշահորդներն են նստած In their private luxurious rooms / Իրանց մասնավոր շքեղ առանձնասենյակներում Talking on behalf of real working class heroes / Ու խոսում բանվորական դասի իսկական հերոսների անունից: You know why? / Գիտե՞ս խի: It’s cool to be a rebel / Ըմբոստ լինելը զիլ ա When you are only a label / Երբ ոչ այլ ինչ ես, քան պիտակ So be a profiteer / Նենց որ չարաշահորդ եղի Labels / Պիտակներ Stop projecting your insecurity on dreamers / Հերիք ա քո բարդույթները երազողների վրա պրոյեկտես When all you care is to protect your privacy / Երբ ուշք ու միտքդ մենակ սեփական գաղտնիությունդ And some pocket money / Ու գրպանիդ փողը պաշտպանելն ա So once again fuck privacy / Եվս մեկ անգամ քունած ունեմ գաղտնիությունդ Motherfucker fuck your privacy / Այ մերաքուն, քունեմ գաղտնիությունդ Your price is the fake democracy / Քո գինը կեղծ ժողովրդավարությունն ա Better later than never / Ավելի լավ ա ուշ քան երբեք To accept that / Ընդունել ա պետք, որ Your father is your motherfucker / Քո հերը քո մերաքունն ա Your mother is / Քո մերը… Free your mother / Ազատիր մորդ Free your father / Ազատիր հորդ Free your mother-fucking tongue from your… / Եվ ազատիր քո մերը քունած լեզուն քո… |

After this short trip across the linguistic border, Lilit’s poem repatriates to the Armenian language and once again becomes culturally acceptable, but also trance-like, and lyrical. Staring at the group of men yelling at her, Lilit read recited:

You moved people,

I want to sing you.[28]

<…>

Pause, passerby,

So I can hug you,

Write you.[29]

No one responded to her calls. A few months later, the woman who sang “pause, passerby, pause” and was ready to hug her adversaries, refuses to join Hasmik Tangyan and meet with Narek Sargsyan. In the documentary, Lilit revealed her wound and the transformation she went through after the conflict:

I sobered up a bit. I understood the possibility of social fear, that it can exist, that it can change your everyday desires, the style of your clothing. And it changed my poetry in a more important place. I mean, my poetry became more soothing for me. I mean, I want to find the place where those men can’t politicize my poetry or that speech. I grew cautious. Words are like action now. And with those words you create your own reality.

The actions of a group of men instilled enough anxiety in this rebellious spirit to transform her world, her poetry. Petrosyan’s post-HuZANK poetry is as layered and phonetically engaging, even though the blades are no longer as sharp. Here’s an excerpt from her post-HuZANK poetry:

You thought I am a special one.

But the truth is I’m just no one

And my unique strength is that

I know I am no one.

I have friends who are also no one.

And we often remind each other

That we are no one.[30]

In the context of the cataclysmic conflict, thoughts of self-depreciation and self-destruction come forth in these lines. Perhaps it’s a covert reference to Odysseus’ ingenious idea to introduce himself as No One to Polyphemus who was eating his friends one after the other. This trick eventually helped him save himself and his remaining friends escape the island, after blinding Polyphemus, without the other cyclops chasing after them, because Polyphemus had told them that No One attacked him, No one blinded him.

Footnotes:

1- «Կանչում են մրրկող ձայներ, / կանչում են դեպի հեռուն. / կաչում են մրրկող ձայներ, / դեպ կյանքը հորդ և յեռուն» Vshtuni, Azat. Excitement and Call, Alexandropol, 1923 (digital edition by Yavruhrat, 2019), p. 14 (in Armenian).

2- Թող զնգա՛ ուժգին պողպատ մո՛ւրճը մեր: Ibid. p. 16.

3- Շոքի,— հոգի, պողպատ: Ibid. p. 19.

4- Պոետ֊-պողպատ-հանճար: Ibid. p. 20.

5- My improvisation based on a stanza from “But Could You?” by Vladimir Mayakovsky (1913): «A вы / нектар собрать / смогли бы / из фонтана железобетонных цветов» (But could you / now / perform a nocturne / Just playing on a drainpipe flute? (tr. Dmitri Smirnov))

6- Hofstede, Geert. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind, Third Edition. McGraw Hill LLC. Kindle Edtion, 2010, p. 109.

7- Ibid

8- Ibid. 201

9- Ibid. 202

10- Following detention, a detainee is obligated to provide a written explanation of whatever became the cause of detention.

11- Ibid. p. 126.

12- Hofstede, Geert. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind, Third Edition. McGraw Hill LLC. Kindle Edtion, 2010, p. 77.

13- «Քո երգո՛ւմ` / ըմբոստ հերքո՛ւմ հնի… / քո յերկրո՛ւմ` / ճիչ ու բերկրում հիմի»: Vshtuni, Azat. Excitement and Call, Alexandropol, 1923 (digital edition by Yavruhrat, 2019), p. 8.

14- «Բեթհովեն մի ստվեր ե անուժ / մեր վաղվա յերգերի դեմ հսկա». Ibid. p. 50.

15- «Մի Դանթե՞, կամ թե / Պուշկի՞ն ես դու.— / չե՛, ի՛մ ընկեր, / ավելի ուժգի՛ն ես դու…». Ibid. p. 8.

16- «Մասիսը հին՝ առասպել չար ու չնչին». Ibid. p. 41.

17- «ՀուԶԱՆՔ ու ԶԱՆԳ» նախագծի ահազանգը (The alarm of Excitement and Call), online essay at https://hetq.am/hy/article/109409.

18- «Մենք նո՛ր ենք, մենք պոետներ ջահել, / մեր մուսան ելեքտրիկն ե, շոքի՛ն» from Vshtuni, Azat. Excitement and Call, Alexandropol, 1923 (digital edition by Yavruhrat, 2019), p. 50.

19- «Սահմաններ չունի հիմա աշխարհը / Նոր է, անծիր»: (The author is unknown. It’s either Kara Darvish or Gevorg Abov)

20- «Կա, կա, կա, կա / Լոմկա, լոմկա (կամ միգուցե` լոմ կա) from https://anchor.fm/lilit-petrosyan9/episodes/huzanq-u-zang-ed9cn8

21- «Ու մե՛նք, ամենքս մե՛կ,— / պոետ-պողպատ-հանճար…» from Vshtuni, Azat. Excitement and Call, Alexandropol, 1923 (digital edition by Yavruhrat, 2019), p. 50.

22- «Ածող հավերի ածանցյալ ե՞ս դարձել / Մտացածին հանճար ե՞ս, / Թե՞ ճար գտնես / Հանճար ե՞ս, թե՞ ճար գտնես: / Ճարտար ե՞ս: / Դե ճառ ասա, / Որ ճար գտնես» from https://anchor.fm/lilit-petrosyan9/episodes/huzanq-u-zang-ed9cn8

23- «Հրաշքներ բաժանողից էլ մի քիչ կանաչ նվեր բեր / Տեսնեմ` ի՞նչ նպատակ ա քեզ քոր տալի, ապե» from https://anchor.fm/lilit-petrosyan9/episodes/huzanq-u-zang-ed9cn8

24- Hofstede, Geert. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind, Third Edition. McGraw Hill LLC. Kindle Edtion, 2010, p. 126.

25- Dewaele, Jean-Marc, “‘Christ fucking shit merde!’ Language preferences for swearing among maximally proficient multilinguals”, see here.

26- Ibid.

27- Nayiri Hunanyan led an armed attack on the Armenian Parliament in 1999, assassinating seven members of the parliament, including the Speaker and the Prime Minister.

28- Մարդ հուզեցիր, / ուզեցի երգեմ քեզ

29- Կաց անցորդ, / Որ գրկեմ քեզ / Գրեմ քեզ

30- Դուք կարծեցիք` ես հատուկ մեկն եմ: / Իսկ ճշմարտությունն այն է, / Որ ես պարզապես ոչ մեկն եմ / Եվ իմ յուրահատուկ ուժն այն է, / Որ ես գիտեմ, որ ոչ մեկն եմ: / Եվ ունեմ ընկերներ, / Ովքեր նույնպես ոչ մեկն են: / Եվ մենք հաճախ իրար հիշացնում ենք, / Որ մենք ոչ մեկն ենք: