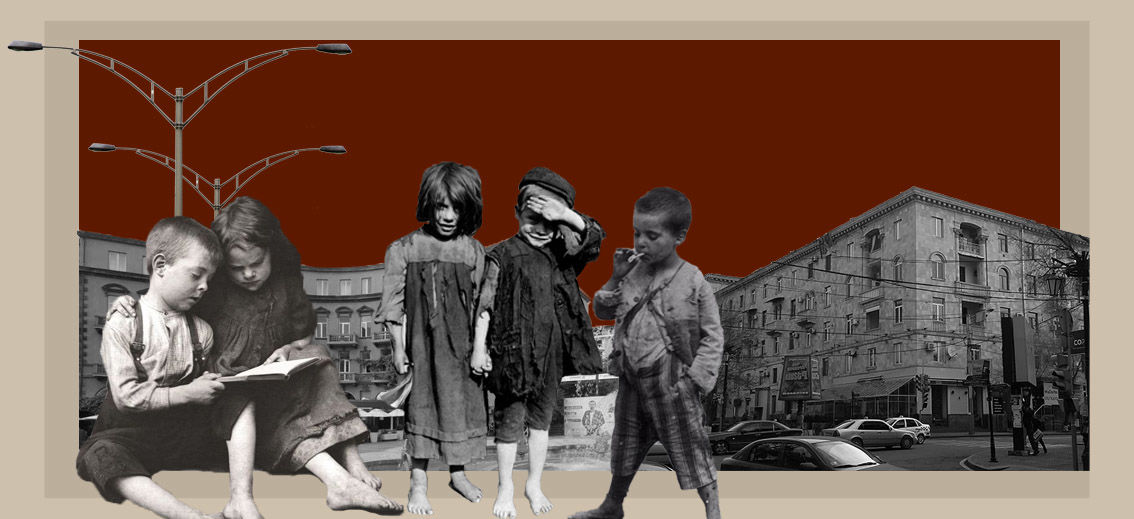

“I was very young when I started working at the Fund for Armenian Relief (FAR),” says Mira Antonyan, the director of FAR’s Children’s Support Center Foundation. At first, the Center, which was established in 1999, focused on finding and collecting children begging on the streets. For the past 20 years, Antonyan has borne witness to the fate of so many lives – hungry and lost children, abused women, abandoned men. Her stories are endless.

“Late, one cold winter night, the police had found a number of abandoned children and reached out to us,” Antonyan explains. She, along with her colleagues went to fetch them. “There were 10-15 children, hungry, with torn clothes, hugging each other so they wouldn’t freeze. Sometimes, I am surprised how I get through the night,” she says. Although Antonyan has been doing this for over two decades, she says nothing is ever normal: “The fate of these unfortunate children can never be normal.”

Located in the Zeytun district of Yerevan, FAR’s Children Support Center is perceived by many as an orphanage. However, the Center is not an orphanage nor has it ever been one. During the Soviet years, the building was used as a center for taking in and reallocating children, also known as a receiving-reallocation station, an unusual term.

“In 1937, these types of stations were created in all Soviet republics as a special kind of shelter for those children whose parents were exiled or were living on the streets due to poverty,” explains Antonyan. “There were many reasons. One of the buildings in the vicinity of the Children’s Support Center was built for this purpose.”

Police officers would bring children they found on the streets to this receiving-reallocation station. The social workers at the station would supervise the children until they were either sent to an orphanage or were returned to their families, if that was possible. The receiving-reallocation station operated until 1996, when it lost its state funding.

“There was a great number of children on the streets during those years,” recalls Antonyan. “They were everywhere – in front of the Armenia Hotel (since renamed as the Armenia Marriott Hotel), on Abovyan Street, in Gyumri and Vanadzor. There were nearly 3,000 children prowling the streets. Their stories were all different. Many parents started using their children as a way to ‘earn’ money. It was the parents who sent their kids to the streets.”

The police soon asked the Children Support Center to renovate the receiving-reallocation station. The Center invested in the project; however, it refused to hand the building back over to the police. During the opening of the Center, they told their donors that the building had to become a place that sheltered children, a support center, a new hope.

“At the time, I was working as a supervisor for social workers at the Vardashen School for Médecins Sans Frontières [Doctors Without Borders],” says Antonyan. “I was offered to join the project, and that’s how I ended up here as a social worker. We called the project the Building of a New Hope.” The Children’s Support Center came to an agreement with the police to use the building through a 99-year lease. “I have to point out that this cooperation was very successful because, at the time, we had a department within the police that supported us on different issues,” explains Antonyan. It wasn’t always easy working with the parents of abandoned children and the police were often forced to interfere because no other way was possible.

“There is a woman whose fifth child is at the Center now. She used to live in Jrvezh and had two boys. Then she had twins and then a girl,” says Antonyan. “In the beginning, she lived with her husband and two children in a studio apartment but because they couldn’t get along she would sleep in the kitchen with her children. The rest of the apartment was considered her husband’s. I don’t want to get into the details of the conditions there. It was awful. The woman would go to one administrative city district to another and collect money and then go home. That was her life. Her kids, in turn, would beg near the Opera.”

In February 2000, after a comprehensive training program, the Children’s Support Center accepted its first nine children, three of whom were siblings.

“I remember it as if it was yesterday,” says Antonyan. “The siblings were from Armavir marz. The police had found them in a pit near the Barekamutyun metro station. I don’t want to remember that case. There were 16 children who would sleep in that pit every night. We had one child, a wonderful boy. We brought him to our Center, but he had tuberculosis. They couldn’t save him.”

Antonyan says it’s one thing to see children that are being cared for in an institution, it’s another thing when you go and see abandoned children in the streets in terrifying conditions. The Children’s Support Center was accepting children from all over the country—all of them from cruel and difficult conditions.

“Street life has its own laws. It’s a terrifying ‘school,’” admits Antonyan. “There was a person called the ‘onlooker.’ Everyone had to answer to the onlooker and bring him the spoils they had collected that day. Woe to that person who tried to trick him.” Antonyan says there were many children for whom, unfortunately, begging had become a way of life. “Our attempts to bring them into a new phase in life fell short,” she says. “There was one young person – I won’t mention their name or where they lived – do you know how many times we brought this young person to our Center? It was all in vain. The street called out to them.”

At the time, there were many mothers who would have children for the sole purpose of using them for begging. Or they would take somebody else’s child and sit in a corner on the street with a hand reached out.

“It’s hard for me to recall all of this because, for my whole life, I’ve had to deal with the fate of many children. I’ve witnessed how, as a result of the hard work of my colleagues, lives have been saved,” explains Antonyan. “A child’s fate depends on the work we do, how we intervene in their lives and if a donor donates or not. What worried me the most was that there were children who enjoyed that lifestyle. There was no supervision, no mother to scold them. However when we sat down with these children and spoke with them, we understood how deep and mature they were,” says Antonyan.

Many parents opposed the work that the Support Center carried out. Antonyan says they were misunderstood by everyone. Someone would always find something they were displeased about. The atmosphere in which they worked wasn’t a happy one.

“I can recall people from neighboring buildings constantly complaining about us and our children, claiming that we made a lot of noise, or that the children had stolen things from their courtyards, etc. They brought a child to us from Vanadzor, who had run away from his orphanage several times. He was not one of the well-behaved children. He entered the kitchen and saw small baskets filled with bread on the dining tables. He was surprised. He picked one up and asked if this is what fresh bread smells like. He would take pieces of bread and keep them under his bed. Eventually, we got him to understand that the bread was his and no one was going to take it from him. It was his portion,” says Antonyan.

The most indescribable stories they witnessed were those involving abuse—of both girls and boys. During those years, there were many cases of abuse against boys. Both sexes are equally vulnerable.

“It’s possible that girls are naturally more vulnerable because, if they’re abused, they may never want to have a family life or be sexually active. There is pain you can’t get rid of. It gets stamped into you,” says Antonyan.

Until 2004, the Children’s Support Center focused all their work on putting an end to child begging. After 2004, the number of children begging decreased, thanks to the work done by the state and different organizations. Hence, the Children’s Support Center was able to focus their field of work on more inclusive issues. It was during this time that Antonyan decided to temporarily halt her work at the Center.

“I’m talking about this for the first time,” admits Antonyan. “Back then I needed to get away. I wanted to go and conceptualize everything I have been witness to. I admit now that I just couldn’t take it anymore. I had three children of my own. I would take all the stories home with me and I couldn’t let them go. I was very depressed. I started my academic work and started working at Yerevan State University full-time. I was also able to complete my Ph.D., but I couldn’t stay away for long. When the management invited me to join them again, I returned as the director.”

Antonyan went to New York City, where they were discussing the work of the Children’s Support Center: What kind of services should it provide? What needs did Armenia have? A former social worker herself, she developed a program. She believed that the abuse that children faced in the streets had moved into the family. Many children were facing physical and mental abuse from their own parents.

“It turns out that we were successful in returning the child to the family. However, was that the best environment for them? That was questionable. How can we talk about a child’s best interest if they are being abused?” asksAntonyan. “Children, even today, are not protected in our country, and this is a major issue. I proposed that we shift our focus to preventing abuse, as well as supporting those children who were being abused or witnessing the abuse of one parent by another. The latter is also important because this is another type of unfortunate circumstance that also affects a child’s mental state and future development.”

For Antonyan, it was imperative for experts to develop their skills further because social workers at different institutions are still lagging in terms of expertise. Antonyan is convinced of this. As a professor at YSU, she teaches her students that social work is closely connected to human lives. Hence, it should not be taken lightly. They have to be extremely dedicated and comprehend the full scope of their responsibility.

Soon, the Children’s Support Center started working with a new fervor. In 2006, Antonyan proposed to establish a child’s protection network that would include different NGOs. Several projects and proposals were developed under this framework and were presented to the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs. Their aim is to consolidate the experience and knowledge of NGOs with state institutions. All in the best interest of the children they serve.

“At our Center, the workers are often considered mothers and fathers to the children and that is how they refer to us,” explains Antonyan. “We are often forced to take on this role for them. I remember one case when a mother had left her four children and husband. Her excuse was that she didn’t marry for love. She had abandoned her children and moved in with her lover. The husband was in the military. He would be stationed for 15 days, and then come home for 15 days. He brought the children to our Center. I remember them well. We worked with that family for a long time, constantly worrying that the father would take them to an orphanage. Some time passed. One day, the father, who would visit often, came in with a woman. You should have seen our joy! The children were going to have someone who was ready to love them. I wish all my memories had a similar ending. However, alas, there were many unfortunate cases. These painful and bitter fates are what forces us who work at the Children’s Support Center to never, under any circumstances, lose our grip and close shop.”

The Children’s Support Center is still at full capacity today. Laughter and crying are often heard together. They still believe in miracles here, and hope that one day all the children will return home.

Future Prospects for Foster Care for Children with Disabilities in Armenia

A child’s right to family life is enshrined in Armenian and international legal documents and considered a priority in Armenia’s 2017-2021 Strategic Plan on the Protection of the Rights of the Child. Here is EVN Report's White Paper about specialized foster care for children with disabilities.

Read morealso read

The State and the Care of a Child

EVN Report discusses the policy of deinstitutionalizing orphanages and providing care for children with disabilities within the context of their right to family life with Deputy Minister of Labor and Social Affairs Zhanna Andreasyan.

Read moreThe Place Where Love Lives

No child should be abandoned and no child should live in an institution. This is a story of a group of mothers whose concern, love and compassion is changing the lives of children with disabilities and their families.

Read moreMy Big and Unusual Family: SOS Children’s Villages

The Kotayk SOS Children’s Village was established in 1988 following the Spitak earthquake to offer immediate aid to those children who had lost their parents. Today, over 30 years later, SOS Children’s Villages continue to support children and their families in three locations across Armenia.

Read moreThis project is funded by the UK Government’s Conflict, Stability and Security Fund.

The opinions expressed are those of the authors’ and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the UK Government.