Introduction

A child’s right to family life is enshrined in Armenian and international legal documents and is considered a priority in Armenia’s 2017-2021 Strategic Plan on the Protection of the Rights of the Child. The Armenian Government is taking steps to organize care for a child within his/her biological family, and if not possible, by administering family-based and other types of alternative care. Armenia’s deinstitutionalization policy was developed for this purpose. Its aim is to close down or restructure residential care institutions for children and in its stead organize childcare and education within a family- and community-based environment.

International experience, as well as research on child development, has shown that 24-hour care institutions do not provide favorable conditions for the complete development of a child. Hence, a family environment is the most favorable environment for a child’s care and protection.

According to data from the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs of Armenia, as of June 2019, 835 children continue to be cared for in state and private orphanages. This number has decreased over the years (from 975 children in 2008 to 835 children in 2018). However, the decrease in the number of children in orphanages is due to children without disabilities being removed from orphanages. Meanwhile, the number of children with disabilities continues to remain the same. According to the same source, 468 of the 835 children have disabilities. Based on an ad hoc public report by the Human Rights Defender of Armenia, from 2015 to 2018, 97 of the 181 children moved from maternity wards to orphanages had health issues. Steps taken by the state till now were aimed at restructuring general orphanages and boarding institutions. This has created unequal and discriminatory conditions for children with disabilities since it’s delaying the realization of their right to family life.

In the case when, as a result of deinstitutionalization, it is not possible to return the child to their biological family and guardianship (care by a close relative) and adoption are also not viable options, institute of foster care is a state-sponsored alternative option which aims to ensure a child’s right to family life. Despite the fact that foster care was legally established in 2008, as of 2018, only 75 children have received care in foster families, five of which have disabilities.

As a result of legal reforms that have taken place during the past two years, foster care as an institution was given a more comprehensive legal definition allowing this type of alternative care to be implemented in wider capacities. On the other hand, public perceptions of people with disabilities are still discriminatory which creates a supportive environment for many children with disabilities to end up in institutions.

Research carried out on child development has shown that the ideal environment for child development is the family. An institution can be beautifully equipped and have qualified staff, however, it can never replace the environment necessary for a child’s development. Within an institution, a child is more dependent, indecisive, unaware of his/her rights and is isolated from society. This is more apparent with children with disabilities.

Taking all of this into consideration, it is necessary to develop a targeted approach on the deinstitutionalization of institutions providing care for children with disabilities and on specialized foster care as an alternative method to organizing family-based care for children with disabilities.

This white paper aims to explore the legal and practical possibilities of organizing foster care for children with disabilities, the international experience in this regard, factors causing obstacles and to provide recommendations to further develop the institute of foster care in Armenia.

1. Why Institutions Should be Abandoned in Favor of Family-Based Care

Deinstitutionalization, the process of resettling children into family- and community-based environments from institutions started in the West in the mid-20th century. Large campaigns for the protection of human rights, as well as the expansion of scientific research on child development further solidified the idea of deinstitutionalization. This wave spread throughout Europe and into other parts of the world.

Why is family-based care more favorable than institutions?

- A child’s right to family life. Every child, no matter his/her characteristics, has the right to family life. Article 41.2 of the Family Code of Armenia states, “Every child has the right to live and be nurtured within his/her family, to know his/her parent, to receive care by them (however possible), to live with them, with the exception of cases that are not in the child’s best interest.”

Within a family environment, a child can attain his/her other rights.

- The favorable impact family has on a child’s development. Children in institutional care are disconnected from their families and communities. In terms of age and type of disability, they reside within homogeneous groups; in conditions of group identity they lose their selves, they don’t feel affection and love from their care providers, there is no individual approach and they follow a set daily schedule. Research shows that children from care institutions that return to a family environment, including adoptive and foster care families, become more successful later on in life.

- Cost-effectiveness from the perspective of the state. When observing the issue in the long-term, family and community-based care are more cost-effective for the state, than even the most valuable and well-furnished institutions.

Financial analysis carried out by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) confirms that organizing a child’s care within a family and investing in community services are more cost-effective. This makes it possible to invest in the expansion of a network of community-based social services for more children, thus, creating a favorable environment to take advantage of these services for every child residing in the community from a young age. By providing accessible services, children can stay with the family and community, thus, fostering a child’s natural development.

With deinstitutionalization, the most favorable method for childcare is within his/her biological family. If a child’s future care within his/her biological family is impossible, then care is organized through alternative methods.

The Armenian Government’s Decision N 551[1] states the following as different types of alternative childcare:

1. Adoption

2. Guardianship

3. Foster care (organizing a child’s care through some type of foster family)

4. A child’s care in social daycare centers

5. A child’s care in child support centers

6. A child’s care in boarding schools

EVN Report’s the Reader’s Forum section is meant to create a space and platform for readers to be co-creators of engaged, credible journalism, to have a voice in driving policy development and to collaborate in bringing about a more informed public discourse. We want you, our reader, to be part of the conversation and that is why we are inviting you to read our White Papers, leave a comment, ask a question, make a recommendation and be part of the conversation.

Table of Contents

Main Concepts

Introduction

Methodology

1. Why Institutions Should be Abandoned in Favor of Family-Based Care

2. History of Foster Care Development in Armenia

3. Main Factors Hindering Foster Care for Children with Disabilities

3.1. Discrepancies in State Data and the Shortcomings in Information Systems on the Organization of Care for Children with Disabilities

3.2. Legal Issues on Regulating Foster Care for Children with Disabilities

3.2.1. International Reaction

3.2.2. Legal Regulations in Armenia

3.3. Public Perceptions on Disabilities and Foster Care for Children with Disabilities

3.4. The Limitations of Social Service Networks

4. What does International Experience Suggest? Lessons Learned

5. Recommendations

Reference List

Methodology

This study is based on the analysis of the following:

a) Legal documents regulating the field

b) International documents related to the field and corresponding recommendations

c) Armenian and international studies and reports

d) Official statistics

For this analysis, the Armenian and international experiences were compared to identify problems that can hinder the development of foster care for children with disabilities.

Legal documents and official statistics were analyzed and issues related to legislation regulating the field and gaps in data systems were identified.

Based on the results of this analysis, suggestions have been made regarding the development of foster care for children with disabilities.

7. A child’s care in a general and special (specialized) institution providing social protection to the population, by giving priority to family type institutions, and for children with special needs to specialized family type institutions.

The first three types of alternative care mentioned above are considered family-based care and are prioritized based on the order stated: adoption, guardianship/trusteeship and, in case the two are impossible, foster care.

According to Article 137 of the RA Family Code, foster care is the temporary care and education of a child in a difficult life situation within another family environment that has been chosen by qualified authorities and has been registered, trained and certified until the situation due to which the child has ended up in foster care has been eradicated.

The main principles of any type of alternative care, including foster care are:

1. To keep the child close to his/her familiar community as much as possible

2. Removing them from the family as a temporary and extreme mean

3. Continuous guarantee of care

4. Protection from abuse, neglect, and exploitation

5. To organize care for siblings together [2].

2. History of Foster Care Development in Armenia

The foster care system was first initiated in Armenia in 1999 when an agreement was signed between France and Armenia. This agreement launched the program titled Organizing the Care of Children Aged 3-12 from Orphanages in Foster Families. Through this program, nine children were moved to foster families. [3] However, not until 2008 did foster care receive official status through the RA Government Decision N 459. [4]

In terms of strategy 2014 was an important year. In that year the Armenian Government made changes to the country’s 2013-2016 Strategic Plan on the Protection of the Rights of the Child [5] in order to comply with the UN’s Guidelines for the Alternative Care of Children. Through this strategic plan, the process of dismantling large institutions that provided care and protection for children was given priority, hence, bringing the foster family as a method of alternative care for children left without parental care to the forefront.

In 2016, the Armenian Government approved a concept paper and action plan in regards to providing alternative care services to children in difficult living situations. [6] On July 13, 2017, the Government approved the 2017-2021 National Strategy and Action Plan on the Protection of the Rights of the Child. [7] The latter includes several programs aimed at the protection of the fundamental rights and freedoms of the child by recognizing the child’s best interest and the right of the child to be cared for in a family setting.

The foster family was given a more comprehensive definition in the revised version of the RA Family Code which was approved in 2017. Article 137 of the Family Code states that foster care is the temporary care and education of a child in difficult living situations within another family environment that has been chosen by qualified authorities and has been registered, trained and certified until the situation due to which the child has ended up in foster care has been eradicated.

The clauses in the RA Family Code identify and define what foster care is, its relevant agreements, the rights of the parent and foster child, types of care and time periods, foster care supervision/oversight and paid financial compensation.

The most recent changes to foster care which were aimed at completing and defining the general clauses established by the RA Family Code took place on June 13, 2019[8] when the Armenian Government decided to revoke Decision N 459 made in 2008.

However, throughout the history of institutional restructuring and development of care, there has almost never been any acknowledgment of children with disabilities.

Children with disabilities are housed in three specialized orphanages – the Mary Izmirlyan Orphanage, the Kharberd Specialized Children’s Home and the Children’s Home of Gyumri. In the decision made by the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs on restructuring institutions, not once were these three orphanages ever mentioned.

Children with disabilities have the same and equal rights to be part of the deinstitutionalization process and to attain their right to family life.

It is for this purpose, as well as for organizing future care of children within biological, foster care or adoptive families, it is necessary to observe specialized care as a type of alternative care as well that will be guaranteed by the Government. This will allow children with disabilities to receive care in a family setting.

3. Main Factors Hindering Foster Care for Children with Disabilities

In this section, the main factors hindering foster care for children with disabilities will be examined.

3.1. Discrepancies in State Data and the Shortcomings in Data Systems on the Organization of Care for Children with Disabilities.

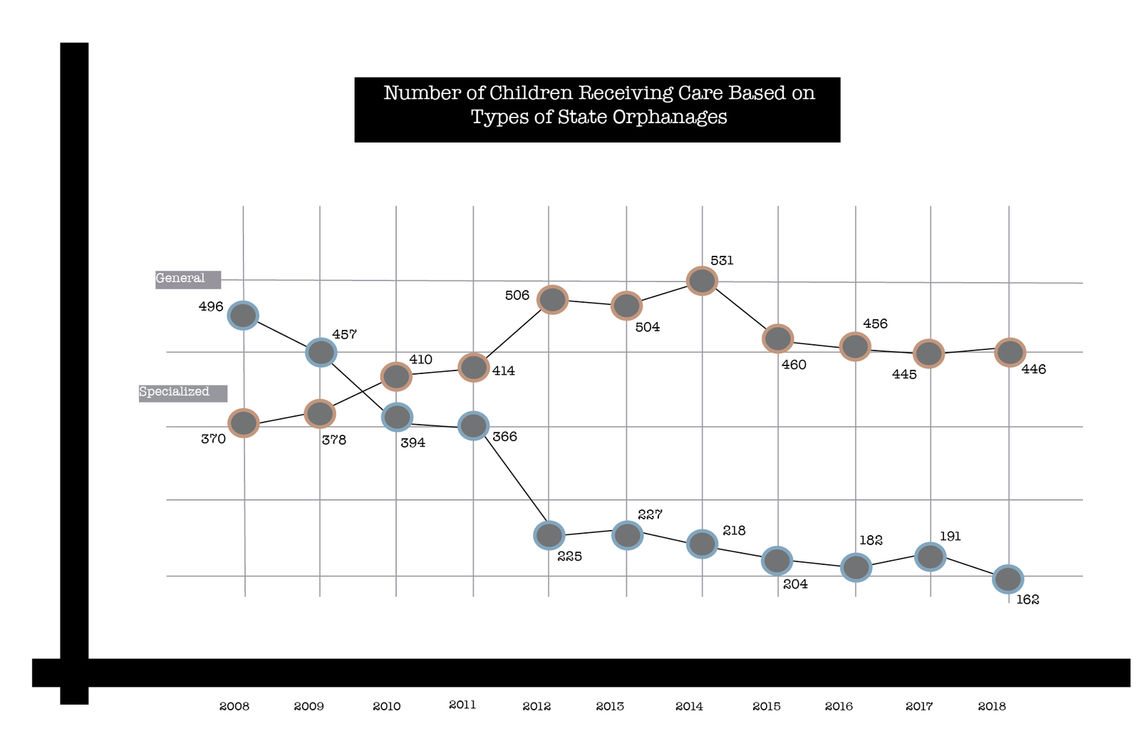

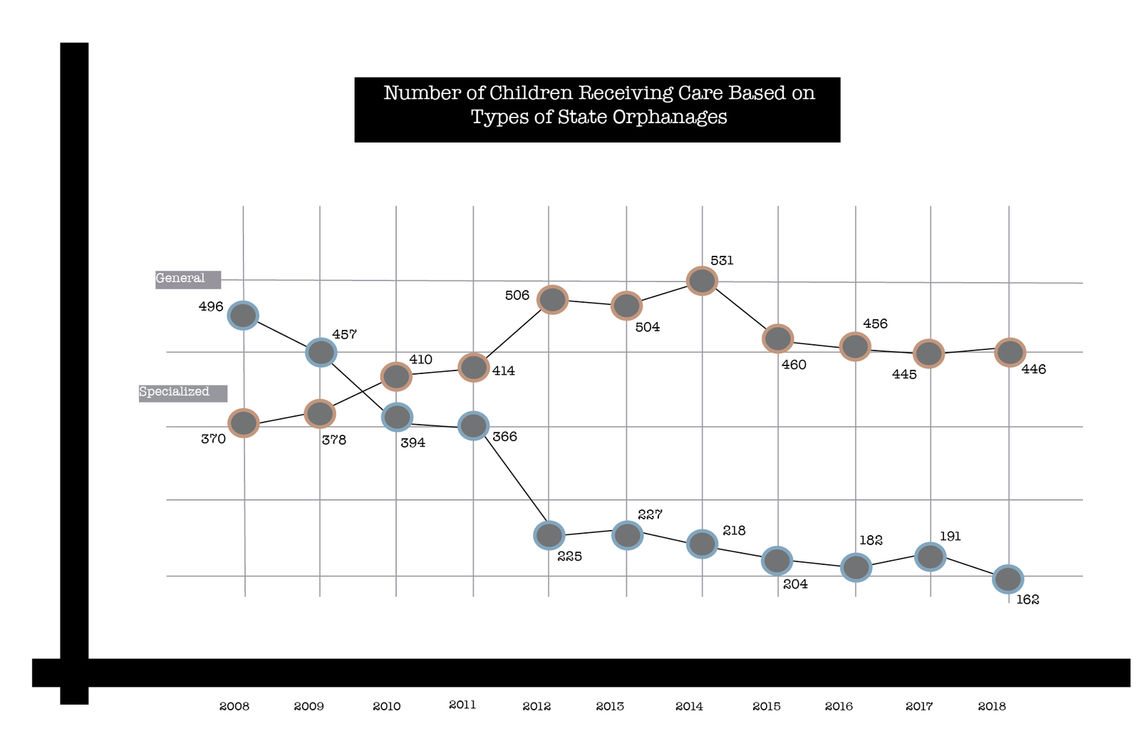

Over the years the number of children living in orphanages has decreased. However, official statistics have shown that the number of children with disabilities who receive care in specialized orphanages throughout the years has almost never changed (the green line in the graph below). According to the “Food Security and Poverty” yearly reports published by the Statistical Committee of Armenia, the number of children residing in general orphanages from 2008 to 2018 decreased from 496 to 162. However, according to the same report, the number of children with disabilities residing in specialized orphanages was 370 in 2008 and 446 in 2018: instead of decreasing, the number only increased.

Source: ArmStat Bank, Statistical Committee of Armenia

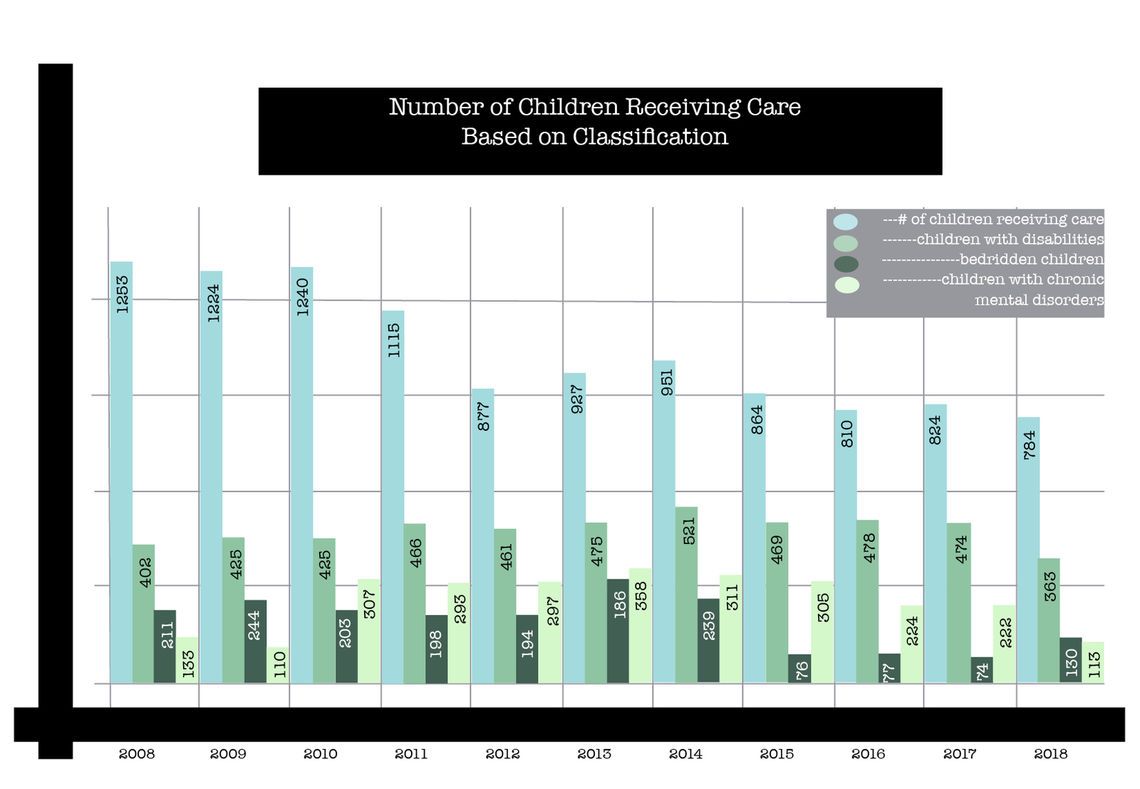

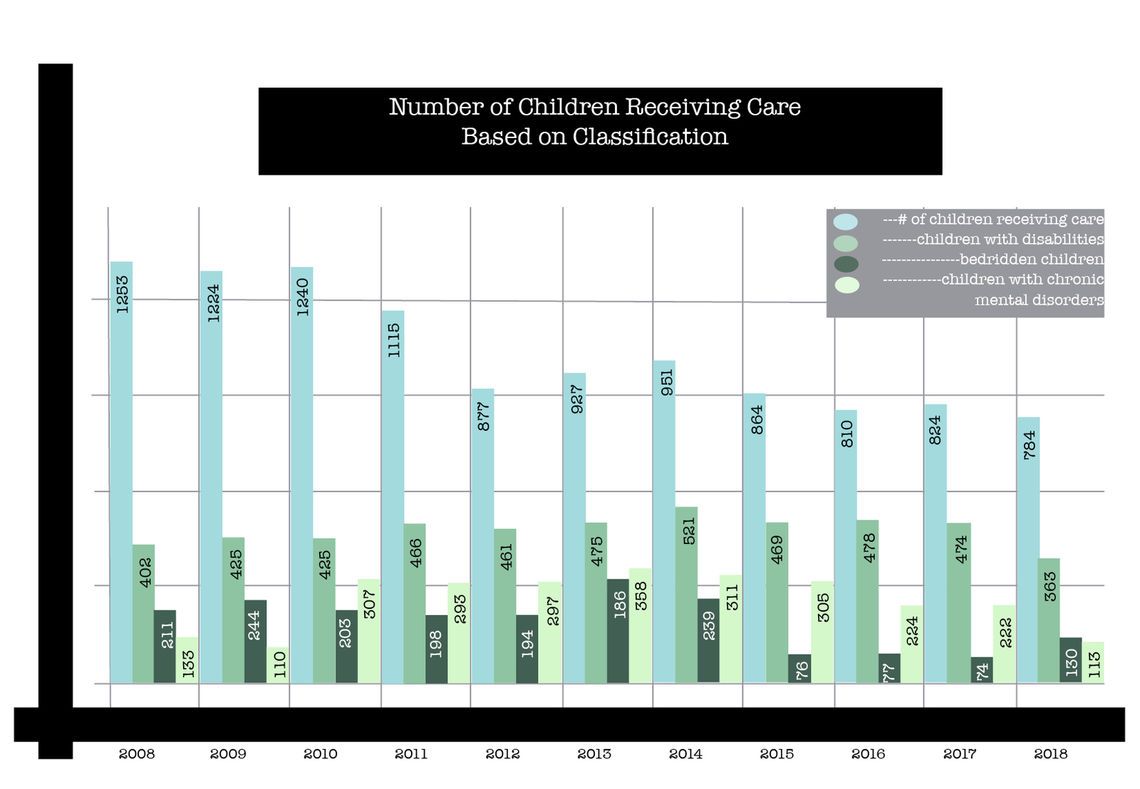

Based on another data modulation by the Statistical Committee of Armenia, despite the decrease in the number of children in orphanages (state and specialized), the change in the number of children with disabilities is quite small. This data allow us to observe not only the number of children with disabilities residing in orphanages but also children that are bedridden and have chronic mental disorders. The number of children receiving care for chronic mental disorders has increased in the past ten years: in 2013 the number reached its peak at 358, whereas in 2008 the number was 113. The number of bedridden children has increased and decreased: from 2015-2017 the number was at its lowest with 74-44 children, however, based on data from 2018, that number increased to 130.

Source: ArmStat Bank, Statistical Committee of the Republic of Armenia

More detailed and desirable data such as the above allows us to better understand where patterns, conditions, and policy should be focused on in the most vulnerable directions.

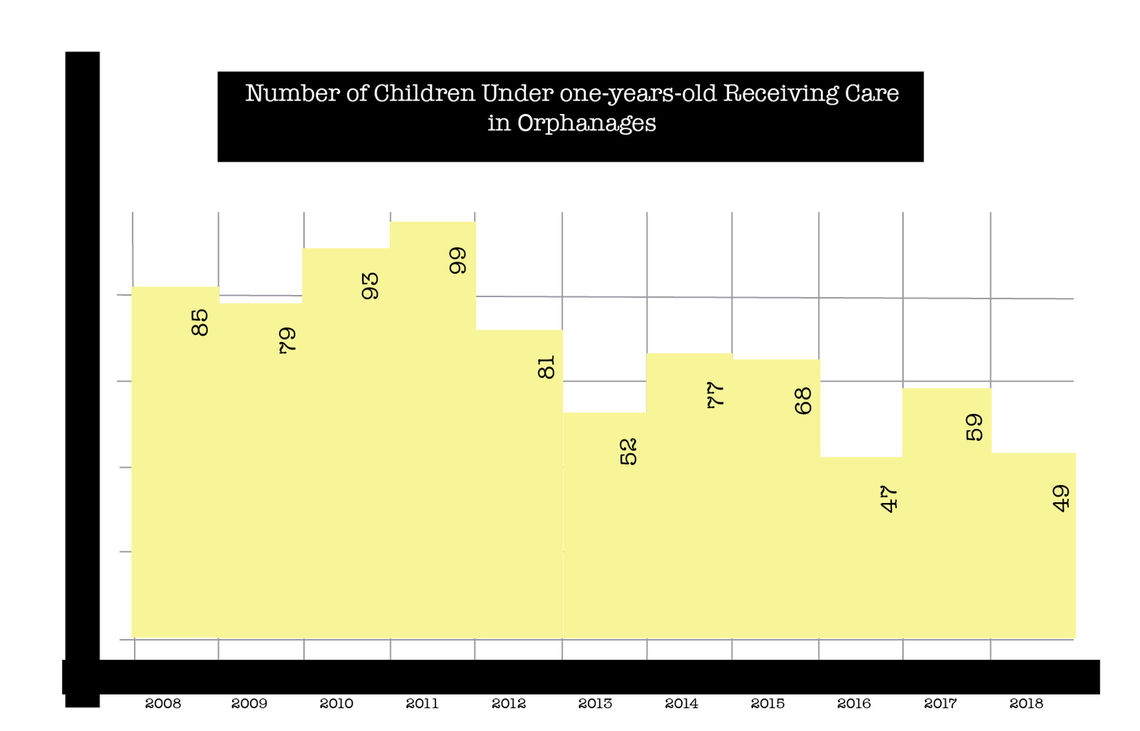

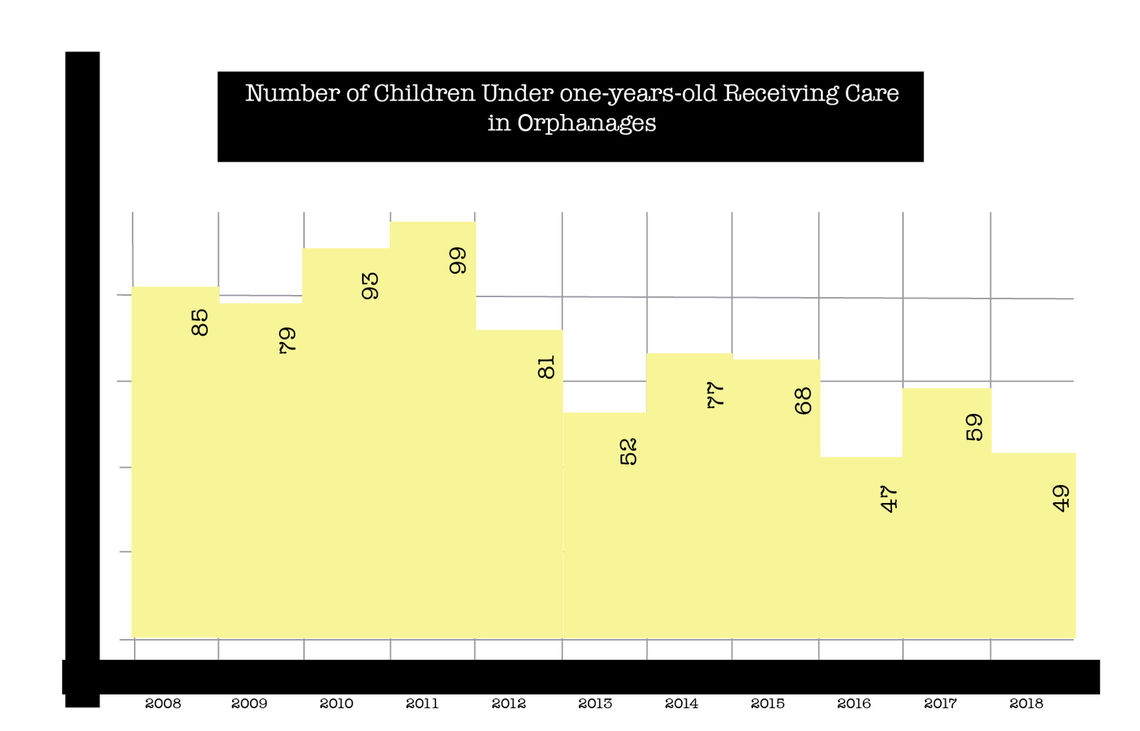

It’s alarming that the number of children until the age of one has remained almost the same throughout the years. This means that the wave of children being sent to orphanages has not decreased. In the past five years, that number has fluctuated between 47-77 children. In 2018, the number of children under age one residing in orphanages was 49.

Source: Armstat Bank, Statistical Committee of Armenia

Moreover, according to the ad hoc public report by the Human Rights Defender, in the past three years, 97 of the 181 children moved from maternity wards to orphanages have health issues.

These numbers indicate that policies on childcare and child protection should prioritize on immediately taking action in preventing children (specifically those with disabilities) from entering orphanages.

In terms of prevention, primary attention should be given to organizing care for children outside of institutions.

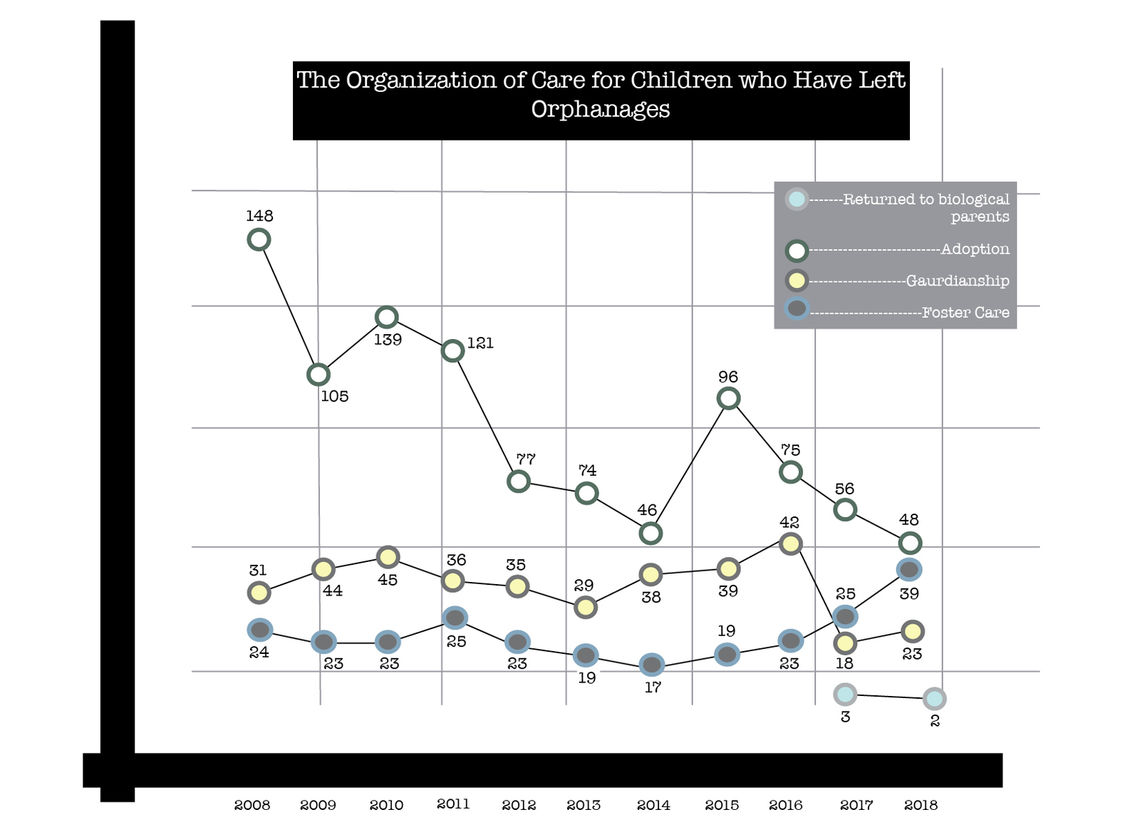

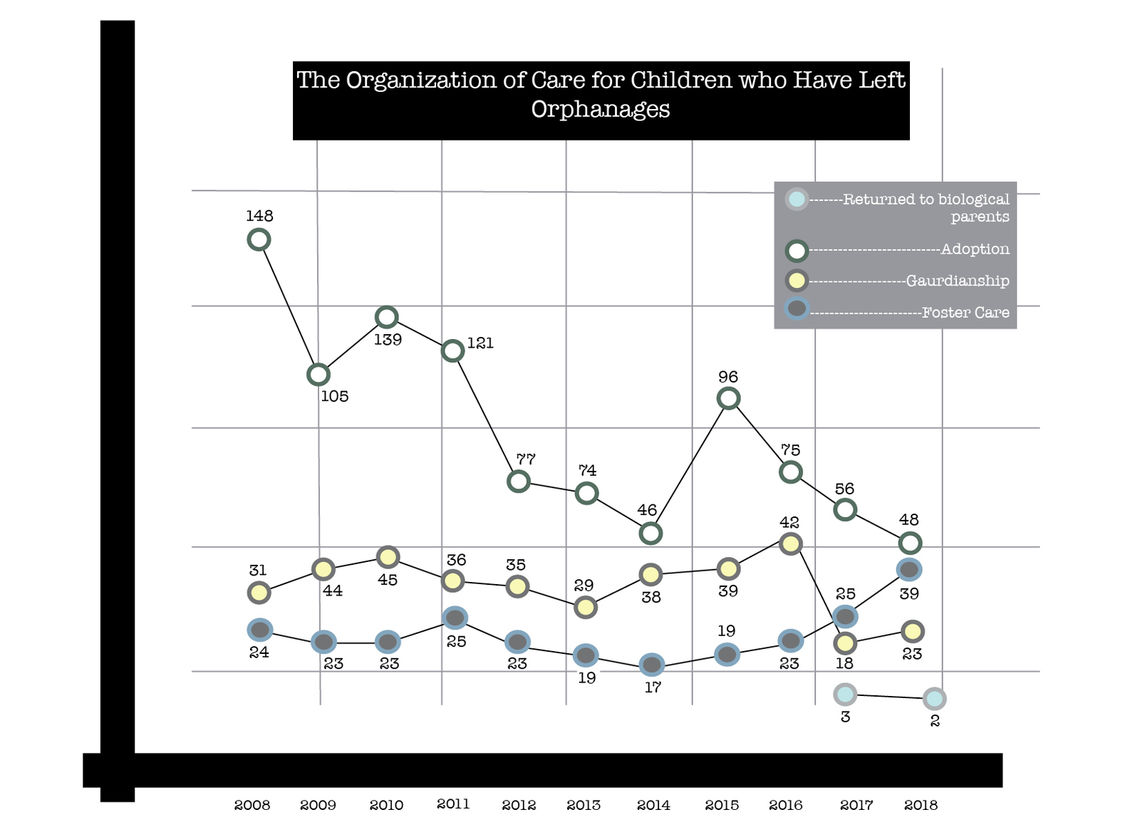

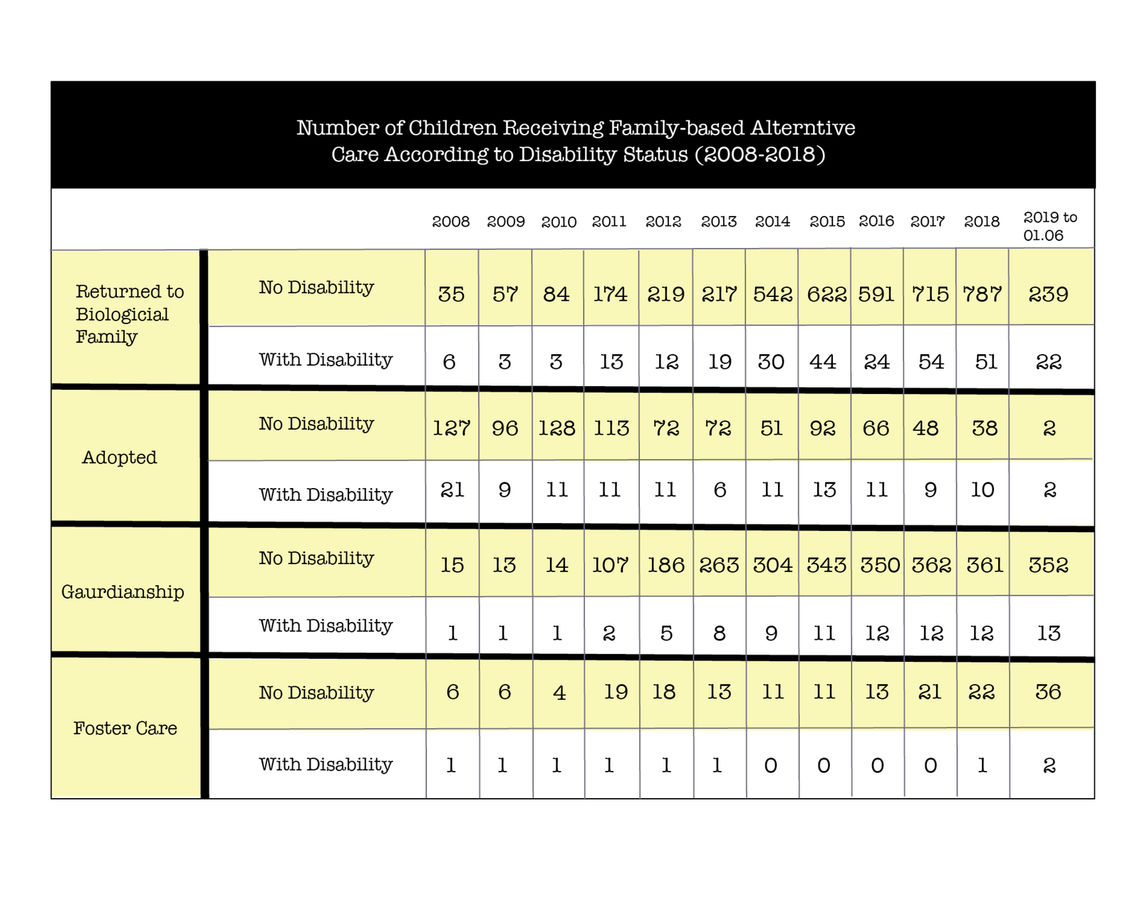

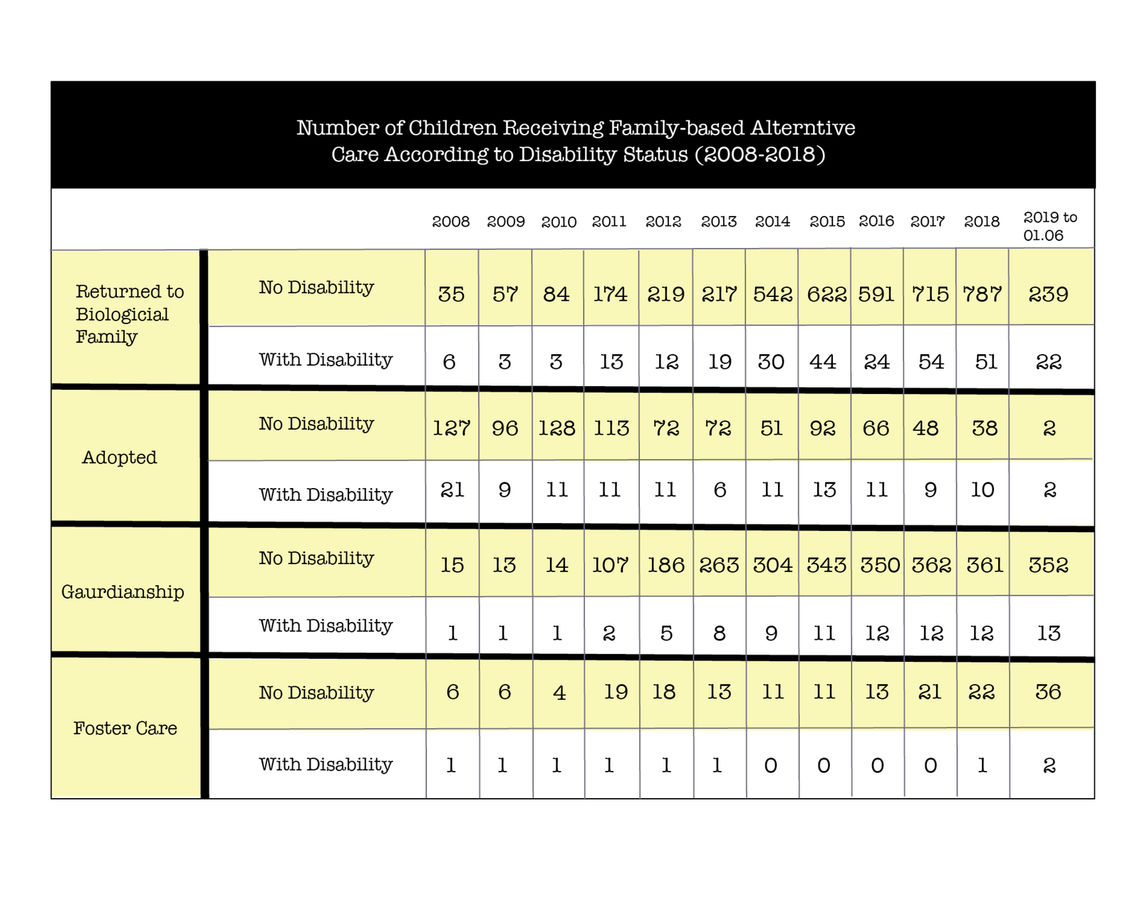

In the past ten years, care for children who have left orphanages has played out as follows: compared to 2008, the number of children adopted from orphanages dropped sharply to 48 children in 2018. The number of children that have returned to their biological families or were placed in foster families has not changed: the number of children that returned to their biological families in 2008 was 31 and 23 in 2018. The number of children placed in foster families increased from 24 in 2008 and 39 in 2018.

Data on the number of children placed in guardian families from orphanages have only been registered for 2010, 2017 and 2018.

Source: Food Security and Poverty Report, Statistical Committee of Armenia

Data from the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs provides more details on how children were moved out of institutions and how much children with disabilities were included in this process. This latter significantly differs from the above-mentioned data because it includes the number of children that have been resettled into family-based care from boarding schools.

Nevertheless, the number of children with disabilities is quite low. However, when comparatively observing the increase in the number of children that have returned to their biological families or have been placed within guardian families, the number of children with disabilities increases as well. For example, from 2008 to 2018, the number of children with disabilities that returned to their biological families increased from six to 51. Similarly, the number of children with disabilities placed within guardian families increased from one to 12. This shows that there is a positive shift toward organizing a child’s care within his/her family or within a familiar environment for him/her.

These positive changes have been proven through several qualitative research as well, that have shown that families are willing to care for children with disabilities if the necessary social and specialized services and education are available.

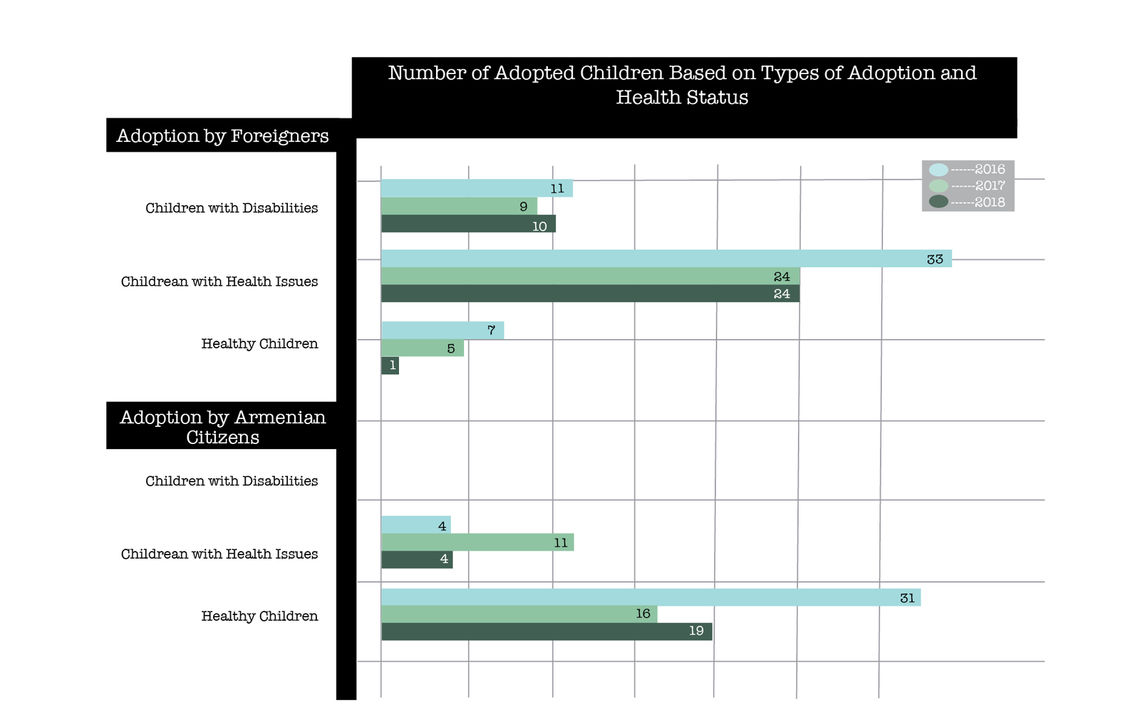

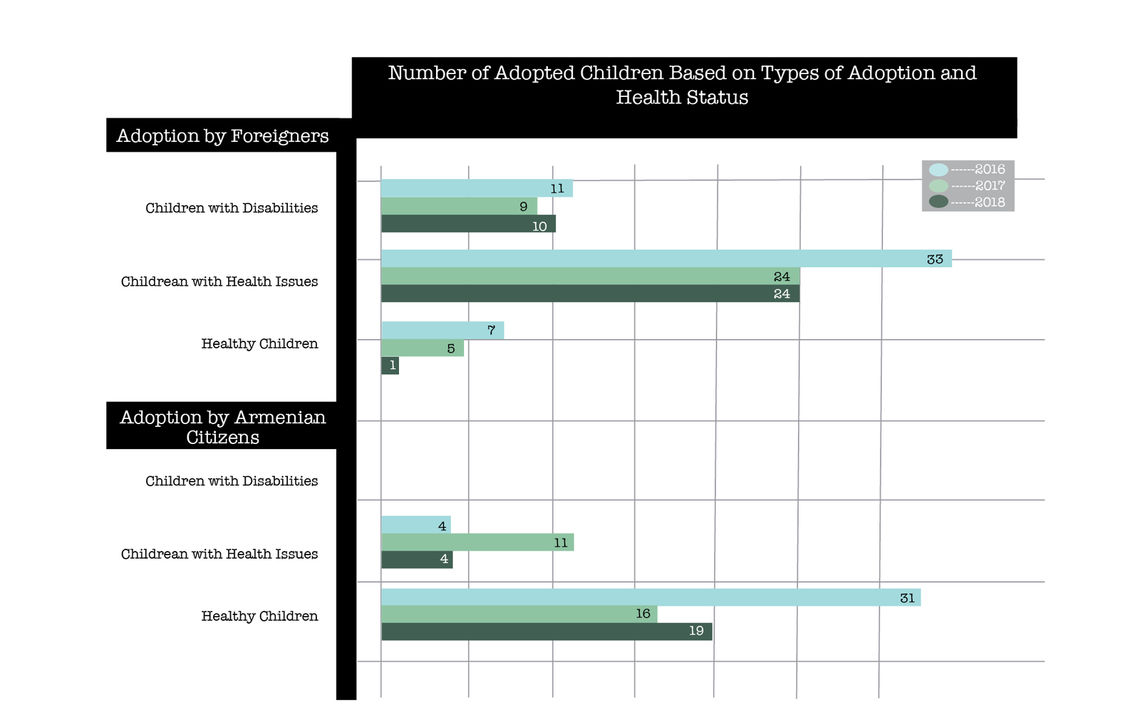

When it comes to adoption, 15-20 percent of adopted children have disabilities. Despite the fact that the number of adoptions has decreased over the years, the number of children with disabilities has not significantly changed. The majority of children who have disabilities are adopted by non-Armenian citizens (9-11 children). According to data from 2016-2018, no child with disabilities was adopted by an Armenian citizen. As for non-Armenian citizens who have adopted children with disabilities, the majority has adopted children aged one to six.

Source: RA Socio-economics Status Report, Statistical Committee of Armenia

In terms of foster care, the number of children with disabilities being resettled in foster families is the lowest. Despite the fact that the number of foster families taking in children have increased, specialized foster care is still not visible. There can be different reasons for this. However, it should be noted that legal regulations regarding foster care, and, specifically, specialized foster care was only developed in the past two years.

Unfortunately, data on deinstitutionalization and the organization of children’s care is limited. This vague picture makes it difficult to conduct a more versatile analysis and to better understand the situation and key issues. Moreover, numerical data from different sources on this topic often differ, indicating a flawed data system. The first steps that should be taken are to collect more comprehensive data to better understand the real essence of the problem (including tendencies and patterns).

The issue with data systems and data integrity is not only about the accessibility of public data, but about comprehensive individual data that would thoroughly represent the situation of a child. This incomplete data system on children is an issue often raised by specialists in the field, including the issue of separating data on a child based on appropriate fields (health, education, social, etc.), the issues of data sharing between different specialists working in child protection, etc.

A joint assessment by MEASURE Evaluation titled “Assessing Alternative Care for Children in Armenia” states that the monitoring and evaluation of care and protection of children are the weakest. It’s essential to establish one unified system for the collection, exchange, and use of data on alternative care. The Manuk Data System established by the Norq Social Services Technology and Awareness Center is a data repository on children that can serve as a foundation for multifaceted data collection and further analysis. However, this system does not contain regulated and comprehensive data. Quite the opposite, it is completely inaccessible outside the state system of child protection.

A unified and multifaceted data system fulfills several important functions and is necessary for every stage of policy development and realization. This type of data system is imperative because:

- It ensures a child-centered approach by the state where the policy’s foundation is not centered on the child having to comply or adapt to the demands of separate spheres, but rather focuses on the child with all of his/her characteristics, needs, and rights. Field-specific support stems from the latter.

- It contains comprehensive data on a child and his/her social, health, education and any other kind of status. For any specialist working with children, the latter serves as a foundation to plan further action.

- It serves as a foundation for policymakers to follow trends and patterns in child protection, to identify the problems and to initiate policy changes based on these statistics. Budgeting in the field, as well as state action prioritization are based on this data.

The abovementioned statistics confirm that organizing care for children with disabilities outside of institutions requires immediate and targeted solutions.

3.2. Legal Issues on Regulating Foster Care for Children With Disabilities

3.2.1. International Response

By ratifying several international conventions, Armenia has taken on responsibilities in regards to the protection of human rights. Armenia has ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, thus, is obligated to create an atmosphere of complete protection of the rights of children and people with disabilities. These documents on the care and social protection of children with disabilities state:

Convention on the Rights of the Child (ratified by Armenia in 1993)

Article 20

1. A child temporarily or permanently deprived of his or her family environment, or in whose own best interests cannot be allowed to remain in that environment, shall be entitled to special protection and assistance provided by the State.

2. States Parties shall in accordance with their national laws ensure alternative care for such a child.

3. Such care could include, inter alia, foster placement, kafalah of Islamic law, adoption or if necessary placement in suitable institutions for the care of children. When considering solutions, due regard shall be paid to the desirability of continuity in a child’s upbringing and to the child’s ethnic, religious, cultural and linguistic background.

Article 23

1. States Parties recognize that a mentally or physically disabled child should enjoy a full and decent life, in conditions which ensure dignity, promote self-reliance and facilitate the child’s active participation in the community.

UN Convention on the Rights of Person with Disabilities (ratified by Armenia in 2010)

Article 23

Respect for home and the family

2. States Parties shall ensure the rights and responsibilities of persons with disabilities, with regard to guardianship, wardship, trusteeship, adoption of children or similar institutions, where these concepts exist in national legislation; in all cases, the best interests of the child shall be paramount. States Parties shall render appropriate assistance to persons with disabilities in the performance of their child-rearing responsibilities.

3. States Parties shall ensure that children with disabilities have equal rights with respect to family life. With a view to realizing these rights, and to prevent concealment, abandonment, neglect, and segregation of children with disabilities, States Parties shall undertake to provide early and comprehensive information, services and support to children with disabilities and their families.

4. States Parties shall ensure that a child shall not be separated from his or her parents against their will, except when competent authorities subject to judicial review determine, in accordance with applicable law and procedures, that such separation is necessary for the best interests of the child. In no case shall a child be separated from parents on the basis of a disability of either the child or one or both of the parents.

5. States Parties shall, where the immediate family is unable to care for a child with disabilities, undertake every effort to provide alternative care within the wider family, and failing that, within the community in a family setting.

The UN General Assembly’s Guidelines for the Alternative Care of Children (ratified by Armenia in 2010, from now on Guideline) suggests specific and targeted steps to realize the clauses in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child by focusing on ensuring the protection and well-being of children left without parental care or are under risk of being left without parental care.

In addition to other international documents, the Guideline reinstates the facts that there is a need for special measures to exclude discrimination on the basis of mental and physical disabilities as well. The Guidelines propose a list of steps that should be taken for the child to receive care within the family, to prevent the need for alternative care, for the reunification of the family, in case of the need for alternative care, determining what kind of alternative care, how to administer, oversee and monitor it.

The following provisions are noteworthy:

52. In order to meet the specific psycho-emotional, social and other needs of each child without parental care, States should take all necessary measures to ensure that the legislative, policy and financial conditions exist to provide for adequate alternative care options, with priority to family- and community-based solutions.

54. States should ensure that all entities and individuals engaged in the provision of alternative care for children receive due authorization to do so from a competent authority and be subject to the latter’s regular monitoring and review in keeping with the present Guidelines. To this end, these authorities should develop appropriate criteria for assessing the professional and ethical fitness of care providers and for their accreditation, monitoring, and supervision.

57. Assessment should be carried out expeditiously, thoroughly and carefully. It should take into account the child’s immediate safety and well-being, as well as his/her longer-term care and development, and should cover the child’s personal and developmental characteristics, ethnic, cultural, linguistic and religious background, family and social environment, medical history and any special needs.

113. Conditions of work, including remuneration, for carers employed by agencies and facilities, should be such as to maximize motivation, job satisfaction, and continuity, and hence their disposition to fulfill their role in the most appropriate and effective manner.

116. Agencies and facilities should ensure that, wherever appropriate, carers are prepared to respond to children with special needs, notably those living with HIV/AIDS or other chronic physical or mental illnesses, and children with physical or mental disabilities.

During the Armenian Government session held on March 10, 2016, the Minutes N 9 was passed on Approving the Concept of Renewing the Procedures for Transferring Children in Difficult Life Situations into Foster Care which was based on the suggestions made in the Guidelines. As a result, the latter’s clauses were taken into consideration in the 2017 reviewed version of the RA Family Code and the Government’s 2019 Decision N 751 on foster care processes.

International organizations regularly raise the issue of organizing continuous care for children with disabilities in care and educational institutions.

In the UN’s concluding observations on the initial report of Armenia, adopted by the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities at its 17th session, raised concern on what kind of care large numbers of children with disabilities receive in institutions by mentioning suggestions made by the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child.

Specifically, it is stated that the Committee is concerned with:

a) Reports on the institutionalization of a high number of children with disabilities in orphanages and residential special schools, including their transinstitutionalization from one institution to another under the guise of deinstitutionalization, and the continuing investment in such institutions;

b) The lack of State support, including early intervention, for children with disabilities and their families, and the high poverty rate among children with disabilities and their families, especially in rural and remote areas;

c) The insufficiency of measures to promote and encourage the adoption of children with disabilities;

d) Various forms of neglect, violence, and abuse against children with disabilities, including in domestic and institutional settings;

e) Stigmatizing attitudes towards children with disabilities

The Committee recommends that the State party:

a) Prioritize the deinstitutionalization of all children with disabilities and their resettlement in family settings, including by promoting foster care and providing appropriate community-based support to parents;

b) Provide children with disabilities and their families with adequate assistance, including early intervention, and implement specific measures to reduce poverty among them;

c) Promote and appropriately support the adoption of children with disabilities;

d) Prohibit and criminalize all forms of violence and abuse against children with disabilities in all settings, including in the home and residential institutions;

e) Promote a positive image of children with disabilities;

f) Implement the recommendations contained in the concluding observations of the Committee on the Rights of the Child concerning children with disabilities.

The Human Rights Watch report titled, “‘When Will I Get to Go Home?’ Abuse and Discrimination against Children in Institutions and Lack of Access to Quality Inclusive Education in Armenia” also mentions this issue and includes the following points in its suggestions:

- Deter any new placements of children in residential institutions;

- Ensure children are not separated from birth families on grounds of poverty, other material deprivations or disability;

- End discrimination in the deinstitutionalization process, including by guaranteeing that the national deinstitutionalization policy includes children with disabilities, and does not discriminate against children on the basis of disability, on the type of disability or high support needs;

- Ensure that financial and other resources allocated to institutions are truly decentralized and redirected to the establishment of community-based services, and do not remain exclusively in transformed institutions;

- Support and strengthen birth families of all children currently in institutions with the aim of reuniting the child with her or his birth family. When identifying and working with families, to include families of children with disabilities on an equally;

- Develop individual plans for each child’s removement from residential institutions, including a plan for community-based support and services. Individual plans should be timely and acted upon in a reasonable timeframe, lest they become obsolete, as family circumstances may change. Ensure long-term caseworker involvement and regular monitoring of the implementation of individual plans;

- Ensure that foster care and adoption systems are fully functional by the time children are moved out of residential institutions. Ensure that systems promoting and implementing foster care and adoption take specific measures to ensure children with disabilities are placed in foster and adoptive families on an equal basis with children without disabilities;

- Potential caregivers should be carefully screened, trained, and monitored to ensure that placement is in the best interest of each child;

This issue was also touched upon by the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights, Dunja Mijatovic’s report on Armenia. In her report, the Commissioner urges the authorities to pursue measures aimed at deinstitutionalization. First and foremost, sufficient resources should be allocated for community support to parents resuming care over their children, including children with disabilities. Should care within the family not be possible, family-type solutions such as foster care – which in principle offer a better solution from the point of view of a child’s best interest – should be implemented.

The above mentioned international documents which have been ratified by Armenia or are prioritized by the Government, unequivocally consider the equal rights of children with disabilities very important. This is why children are the focus of the deinstitutionalization policy. Moreover, it’s necessary to initiate additional measures to support their rights with respect to family life. Foster care, as a family-based alternative care model, has to be observed as an opportunity to settle children with disabilities within a family as a result of deinstitutionalization.

3.2.2. Legal Regulations in Armenia

In the Republic of Armenia children’s rights are defined in the Armenian Constitution, international agreements signed by Armenia, Armenian laws, and other normative legislation.

Legislative regulations on foster care are defined in:

- Family Code of Armenia,

- RA Government Decision N 751 passed June 13, 2019, on Establishing Choosing and Registering People who Wish to Become Foster Parents, Organizing a Child’s Care and Education within a Foster Family, Teaching and Training Those who Wish to Become Foster Parents, Ways of Overseeing the Care of a Foster Child in a Foster Family, Monthly Financial Payment Terms and the Amount for Foster Families, and the Exemplary Forms for Foster Care Agreements and on Revoking the Government’s N 459 Decision passed May 8, 2008,

- RA Law HO-231-N on Social Support passed December 17, 2014,

- RA Law HO-59 on the Rights of the Child passed May 29, 1996,

- RA Government Decision N 631 passed June 2, 2016, Establishing a Charter for the Guardianship and Trusteeship Bodies and Revoking the RA Government N 164 Decision passed February 24, 2011,

- RA Government Decision N 551 passed May 26, 2016, on Establishing Referral Procedures and Standards on Providing Alternative Care for Children in Difficult Life Situations and Changing and Making Additions to the RA Government N 1112 Decision passed September 25, 2015,

- RA Government Decision N 1112 passed September 25, 2015, on Setting Up the Procedures and Conditions of Providing Care for Children, Elderly and (or) Persons with Disabilities, Setting Up the List of Illnesses Based on which Care can be Denied to Children, Elderly and (or) Persons with Disabilities and Revoking Several RA Government Decisions,

- Extract from the RA Government Session Minutes N 30 passed July 13, 2017, on Approving the Timetable of Events for the Realization of the 2017-2021 Strategic Plan on the Protection of Children in Armenia and the 2017-2021 Strategic Plan on the Protection of the Rights of the Child,

- Extract from the RA Government Session Minutes N 36 passed September 15, 2016, on Approving The Event Program for Realizing the Development Concept for Alternative Care Services for Children in Difficult Life Situations,

- Several other decisions and legislative acts.

The above-mentioned legislative acts define methods and procedures for childcare, and how children can attain their other rights. These acts also define the role of a three-stage system of child protection (national, regional, community) and the role of other institutions as well in identifying children in difficult life situations and how to organize their future care within care institutions or outside of them. Specifically, they target procedures for foster care and how to give a child up to foster care, its oversight, as well as community services and how to organize them.

The main two documents legally defining foster care are the Family Code of Armenia and the 2019 Decision N 751. The 2017 reviewed version of the Family Code and the latter Decision clarified the legal procedures for foster care. Several discrepancies were corrected in different legal documents.

By approving the RA Law HO-10-N on Making Changes and Additions to Armenia’s Family Code on December 21, 2017, provisions fostering the procedures establishing the foster family institute were established. Specifically, the types of foster families and the bases for resettling children, their characteristics, the length of foster care, the main principles and direction for overseeing foster families were established. The rights of the child’s birth parents were also defined regarding their right to visit their child, appeal through judicial procedures against the foster family caring for their child and when other issues pertaining to the child are resolved.

The Family Code defines foster care as the organization of the temporary care and education of a child in difficult life situations within another family environment that has been chosen by qualified authorities and has been registered, trained and certified until the situation due to which the child has ended up in foster care has been eradicated. [9]

Article 139 of the Armenian Family Code defines the following types of foster families:

1) Specialized foster family: a foster family that takes in children with disabilities or serious mental issues, learning difficulties, mental or behavioral disorders, children that have gone through mental trauma, as well as mothers that are minors and their children,

2) Crisis foster family: a foster family where the care and education of the child are organized

a) If the child’s parent (or legal representative) is ill;

b) If the child’s parent (or legal representative) is incarcerated or imprisoned, and a decision has not been made on suspending the sentence or release on parole;

c) If a child has to be removed immediately from the parent (or legal representative) when as a result of the latter’s actions or inaction the child’s life or health are threatened;

d) If due to a natural or man-made disaster the child’s parent (or legal guardian) cannot realize and ensure a child’s care and education;

e) If the parent (or legal guardian) neglects the child including not providing proper care and education;

f) If a child’s parents live separately and they cannot agree on where the child should reside or on visitation rights.

3) Vacational foster care family: a foster family where the child’s care and education can be organized continuously or several times a week, including non-working days (holiday, memorials or vacation/days off). Vacation care realizes care and education for children with learning difficulties, health issues or with disabilities that require special care or for supporting parents (or legal guardians) that have other issues pertaining to care and education of their own children.

4) A general foster family: a foster family where the child’s care and education can be organized if the bases for choosing foster families (first three paragraphs of Article 1 of the Family Code) are not available.

Paragraph 4 of Article 137 of the Family Code states that the care and education of children with acute and chronic infectious diseases within a foster family can be organized if the foster parents have gone through relevant training for the care and education of children with disabilities or other special needs or learning difficulties, as well as if the foster parents have the necessary household conditions that meet the child’s needs.

In 2008, the procedures of transferring a child to foster care families, monthly financial payments to foster families for taking in a child and monthly salaries for the foster parents for the care and education of a child and the agreement form for transferring a child to a foster family was approved [10]. This was revoked with the 2019 Government Decision N 751 which defined:

a) The procedures for choosing and registering people who wish to become foster parents, and the organization of a child’s care and education within a foster family;

b) The procedures for teaching, certifying and training people who wish to become foster parents;

c) The oversight procedures for the care of a foster child within a foster family;

d) The procedures and the amount of monthly payment for foster families;

e) Exemplary forms for foster care agreements.

Based on this Decision, regional governing bodies (from now on marzpetarans), and in the case of Yerevan, the city municipality, are to assume the role of the authorized bodies responsible for care. Compared to the former decision based on which the Foster Care and the Trusteeship and Guardianship Bodies were a party in the foster care agreement and were responsible for overseeing foster care, this new decision reduces their functions. Foster Care and the Trusteeship and Guardianship Bodies are still responsible for organizing meetings between those who wish to become foster parents and the child, as well as providing documents regarding the child to the marzpetaran. However, the marzpetarans are now responsible for organizing and overseeing foster care and being a party in the agreement representing the state in addition to its former role of approving foster care.

Many NGOs, foster families, and other concerned parties have often raised concern over the shortcomings of the Foster Care and Trusteeship and Guardianship Bodies in carrying out their responsibilities. Compared to these bodies, the marzpetarans have more resources (including human and professional resources) and can carry out the above-mentioned procedures more competently.

In 2016, the concept of renewing the procedures of transferring children left in difficult life situations into foster care was approved [11], as well as referral procedures and standards on providing alternative care of children in difficult life situations. [12]

Despite the fact that certain legislative reforms have taken place in Armenia, there are still some regulatory issues in the field of alternative care. As a result of the shortcomings in relevant legal foundations and conditions in the protection of the rights of children with disabilities in difficult life situations, the protection of the rights and interests of these children are not carried out properly. Specifically, components of organizing foster care for children with disabilities are not defined in Armenian laws and legislative acts. As a result, specific approaches on how to properly carry out the care of these children in foster families are not defined as well.

In foster care legislation in Armenia, there is almost no separate mention of children with disabilities. In the revised version of the Family Code, specialized and vacation types of foster care are the only types that refer to the organization of alternative care for children with disabilities.

Based on the 2019 Government Decision N 751, changes were made in the financial monthly payments for the care and education of children with disabilities. This payment amounted to the minimum monthly salary set forth in Article1 of the Armenian Law on Minimum Monthly Salary, plus a 30 percent premium.

This new amendment in payment can motivate/promote the institute of specialized foster care. However, it must be noted that since children with disabilities have additional special needs it is necessary to establish an extra dividend for care, taking into consideration that additional care requires more financial investments. For example, caring for children that constantly need diapers requires additional money.

Disabilities are also mentioned in the clauses pertaining to the teaching and training of those who wish to become foster parents [13]. These clauses specifically state that with regard to care, “After completing their training, those wishing to be foster parents to a child with disabilities or health issues can take part in trainings that take place every three years during which the potential foster parents are considered specialized foster parents. The child’s close relatives can opt out of these trainings, except in cases of crisis and specialized foster care.”

Despite the fact that specialized care qualification courses are included in foster care training, it would be preferable if these courses were taught from the start for those who wish to be foster parents of children with disabilities.

Statistics mentioned earlier and warnings raised by international organizations show that it’s necessary to develop appropriate alternative care mechanisms for children with disabilities and include these mechanisms in legal documents. In regards to children with disabilities and their special needs, there is a need to include additional measures stemming from those special needs that would ensure the equal protection of a child. For example, there is a need for specific mechanisms to oversee the care of children with hearing impairments living in foster care. To be able to communicate with a child with hearing impairments additional means need to be taken. If special needs such as the latter are not taken into consideration, implementing unified mechanisms for supervision becomes risky because, for example, by not being able to communicate with the child with hearing impairments, his/her opinion will be neglected.

Field relevant strategic plans and timetables for appropriate action plans also don’t specify children with disabilities when it comes to care. A program of events adopted on September 15, 2016, in the Government Session Minutes N 36, which establishes a development concept for an alternative care service system for children in difficult life situations in Armenia, is the only plan that mentions steps aimed at developing care. This plan includes the identification, training, and creation of data registration of foster care families, placement and periodic updates on data on foster families in the data system of children in difficult living situations. This document also does not specify any steps on organizing the care of children with disabilities outside of institutions and, specifically, on organizing their foster care.

Armenia’s 2017-2021 Strategic Plan on the Protection of the Rights of the Child [14] also mentions foster care. It includes the registration of those wishing to become foster parents in the data system of children in difficult life situations and the development and realization of programs aimed at preventing those children from entering around the clock care institutions. However, there is no mention of children with disabilities in this plan.

The next document that includes children with disabilities is the 2019 Annual Plan on Social Inclusion for Persons with Disabilities and List of Events [15]. This plan specifically states in Article 1.5 the steps to “creating legal foundations for the support of care for children with disabilities within foster care” with the end-result hoping to be, “establishing support mechanisms for the education/rearing of a child with disabilities within a foster family.”

Hence, despite the fact that Armenia has the international obligation to ensure equal protection of rights, legal analysis shows that current regulations have not taken into consideration the peculiarities of the protection of the rights of a child in difficult life situations.

There is a need to promote more measures for foster care for children with disabilities. Even though the new system establishes additional financial compensation for care and education, there is a need to revise the amount foreseen for the care provided depending on the child’s needs and characteristics. Care for children with disabilities, compared to children without disabilities, requires additional financial means.

There are no defined mechanisms for overseeing foster care for children with disabilities. It is necessary to take into consideration all possible circumstances for initiating additional means to properly realize oversight, based on a child’s characteristics.

It’s necessary to initiate programs aimed at organizing care for children with disabilities and supporting foster care. Within the present programs, which are approaching their deadlines and do not have individual components that can be separated, this paper suggests realizing separate targeted action plans aimed at organizing the care of children with disabilities. For example, during awareness campaigns for alternative care, components of specialized and vacation care should be included.

Additionally, it is necessary to review and make appropriate changes to the Family Code and in several legal provisions preceding the Government’s Decision N 751. For example, making changes in the RA Law on Social Support and in the Charter of Guardianship Bodies.

3.3. Public Perceptions on Disabilities and Foster Care for Children with Disabilities

The next factor hindering foster care for children with disabilities is the present public perceptions on disabilities and foster care.

For years, people with disabilities were alienated from societal relations. They were practically “invisible’ in public places. Their social, political and economic participation is very low. As a result of mythicisation of people with disabilities an environment of ignorance and inequality emerged. Within this environment, the lack of public consciousness on disabilities has led people who had children with disabilities abandon them or hide them within the walls of their homes in order to avoid any type of pity, alienation or persecution. As a result, steps toward the inclusion of people with disabilities, including children, have met some obstacles. Local NGOs and international organizations, as well as state bodies, have organized programs which have not been accepted by the public.

A survey [16] conducted by Save the Children NGO on public perceptions on disabilities in Yerevan, Armavir, and Ararat shows that 34 percent of those surveyed has compassion for children with disabilities, 14.1 percent were indifferent and 13.6 percent refrained from answering. Thirty percent of those questioned respected people who had children with disabilities. The majority of the participants, 74.5 expressed willingness to support children with disabilities.

Attitudes toward disabilities differ when it comes to physical and mental disabilities. Citizens are more accepting of people with physical disabilities in public than those with mental disabilities. Based on a survey conducted by the Civilitas Foundation, 95 percent of respondents agreed that children with physical disabilities should be included in society. However, for children with mental disabilities, only 63 percent of those surveyed agreed that they should be included in society. Moreover, 23 percent found it acceptable to give a child up to an orphanage if they had mental disabilities, and 11 percent found it acceptable for children with physical disabilities.

Another survey conducted three years after the Civilitas survey found that only 12.9 percent agreed to the idea of giving up children with mental disabilities to orphanages or specialized educational institutions. There is a sharp contrast in attitudes when it comes to general education. According to the same survey, 40 percent agreed that children with mental disabilities can attend a general elementary school, while 71 percent agreed for children with physical disabilities. Twenty-five percent of the respondents agreed that children with mental disabilities can study in the same classroom with their children, while 40 percent agreed for children with physical disabilities.

In general, social attitudes toward disabilities are more inclusive. However, when it came to questions regarding personal approaches, the responses were more cautious. When asked about becoming foster parents, 5.1 percent were willing. Of those willing, 3.2 percent were willing to foster children with physical disabilities, while 2.5 percent were willing to foster children with mental disabilities. Of the remaining 94.9 percent that was not willing to become foster parents, eight percent agreed that they would be willing to become foster parents if their communities provided supportive/specialized, rehabilitation services and were paid more than what is established by the law.

The root of these attitudes may lie in the mythologization of mental disabilities, equating learning difficulties with mental health problems, and low levels of awareness about learning difficulties.

In regards to the social inclusion of persons with disabilities, the obstacles people with physical disabilities face are more technical, while those with mental disabilities find obstacles within social attitudes. Work needs to be put in toward changing social perceptions.

One of the many reasons children are abandoned in orphanages is due to low awareness of different types of disabilities. The report by the Human Rights Watch includes many individual cases regarding this issue. It should be taken into account that high levels of social awareness are also a guarantee for equality and mutual respect.

On the other hand, this issue becomes difficult to resolve when disabilities are viewed by comparing the physical with the mental. In reality, special needs are diverse and are often connected. When differentiating mental and physical disabilities, the fact that their needs are diverse is left out of the equation and public attitudes are more rigid.

When initiating steps towards raising awareness and conducting research on disabilities, it is necessary to view disabilities as diverse and avoid comparing the physical with the mental. This will allow us to observe how sensitive society is toward different types of disabilities.

Based on research and facts, it can be assumed that there is a serious gap in the awareness of foster care. According to experts, Armenian society has to first perceive foster care positively, and only then organize foster care for children with disabilities.

In conclusion, low levels of awareness on foster care and disabilities creates an atmosphere of inequality which can lead to objections to the idea of foster care for children with disabilities. It is necessary to organize large awareness campaigns to inform society about foster care and to raise awareness of people with disabilities as equal members of society.

High levels of awareness of disabilities will raise the number of people willing to become foster parents.

3.4. The Limitations of Social Service Networks

In Armenia, social service networks, including specialized services, cover little space – focusing only on Yerevan and on those communities that have NGOs and restructured support centers. However, these resources are not enough to completely cover the needs of children with different physical disabilities. Different international and local studies emphasize the need to create social service networks as one of the primary steps for effectively carrying out deinstitutionalization and providing family-based care to children. As a result of current deinstitutionalization processes, children that have returned to their biological families are faced with the inaccessibility of relevant services within their communities [17]. One of the first steps that need to be taken to ensure the right to family life for children with disabilities is to make social services attainable. To make this possible an environment supportive of the special needs and development of these children needs to be ensured.

To make these steps possible, it’s necessary to comprehensively evaluate, on the one hand, the attainability of social services in the communities where the child is placed as a result of deinstitutionalization, and on the other hand, the child’s needs. The next step would be to focus all relevant resources within these communities in order to ensure necessary services.

4. What Does International Experience Suggest?

Deinstitutionalization started in the early 20th century in the Western world. The experiences of the U.S., Great Britain, Spain, and later on of Central and Eastern European countries serve as a great example for assessment and analysis. Based on these analyses, several issues have been identified, which should be avoided during the preliminary stages of the deinstitutionalization process:

Ideology and language

- Human-centered: Policies on social protection are often based on the interests of the state. Hence, priorities are set based on the discretion of the state. This approach does not allow for the issue at hand to be viewed comprehensively and the effectiveness of the solutions set for these problems is low. It is necessary to structure social policies with a human-centered approach. This means to view the person as the focus of the policy, to view the person’s needs in its entirety. The steps the state makes should be taken based on a person’s needs and lead to collaborative solutions. For example, Spain considers the reason their protection policies for children are successful is that they have a holistic/comprehensive approach to every aspect of a child’s development, thus, transitioning from viewing the child as a policy object to the focus of the policy [18]. Legal foundations for such an approach already exist in Armenia with inter-agency social partnership regulations [19].

- Transitioning from the language of assistance to the language of equality: Legal documents on social support and disability are based on approaches on support – a person with disabilities is viewed as someone who uses services and expects support. However, the language of equality views people with disabilities as equal citizens, that require certain support to participate in public life equally. The Human Rights Defender of Armenia mentions this in his report as well: “Children are presented more as subjects of protection than individuals with rights. Meanwhile, by recognizing children as independent and autonomous individuals with rights will make state authorities and private institutions focus their attention on the best interests of these children.” This is especially important for changing social perceptions because at the foundation of these perceptions is language and how we think.

- Participation: “Nothing for us without our participation.” As is during the development, realization and monitoring stages of policies, it is necessary to ensure the participation policy subjects and NGOs advocating for their rights. For example, Hungary is presented negatively in several reports due to non-participatory approach and as a result, delay in deinstitutionalization processes [20].

Oversight

- Absence of a systemic approach by responsible state bodies in the realization of a child’s right to family life – education, healthcare, specialized support, etc.: As a result of this, a child may be left out of educational processes or not be completely included, may not be able to use available health services or not use it completely, specialized support may be flawed, etc. Consequences such as these may be a result of unclear functions and roles of different players and flawed communications between them. As a result, support for children and their families and its oversight are not properly organized.

- Lack of sensitivity of oversight mechanisms during the process of organizing foster care for children in difficult life situations, specifically with disabilities: During the development and revision of oversight mechanisms, it is necessary to pay the utmost attention to their sensitivities in order to address different situations properly. These have to be clearly formulated to avoid personal interpretations and subjective approaches by supervisors.

- Shortcomings in overseeing communication between the child and their biological family and family reunification: Foster families are an opportunity for temporary care with the final aim of organizing a child’s care within their biological family through adoption or guardianship. Keeping constant communication with the biological family and the oversight of this process is of important significance for the quick reunification between child and family.

- Realizing the right to an independent life as an adult: Developing mechanisms and providing relevant support.

Qualification and Training

- Competence and awareness of care providers are one of the most important factors when it comes to organizing care for children with disabilities. Experiences of different countries (Great Britain, U.S., Sweden [21]) show that educating foster families in parenting, human rights, disabilities, childcare characteristics, necessary services, as well as education for these children and healthcare interventions is very important. This has to be personalized, depending on the child’s needs and the environment in which the child is in. The foster family is not only the guarantor of the child’s care but essentially is also the protector of the child’s interest and an advocate for foster care. Hence, it is necessary to give that family relevant skills to be able to carry out its responsibilities properly. Training for foster families has to take place regularly and be based on their own needs.

Information Systems

- Fragmented information and incomplete data present a challenge for child protection. This is because, in the absence of information exchange, collaboration and solid communication systems the support given to the child and their family can be incomplete, including the support given in healthcare, judicial, educational and other systems. These gaps can have negative consequences, specifically for children in foster care families [22].

Social Services

- The right to family life for children should not be realized at the expense of violations of other rights. The state should focus a lot of attention on the accessibility of social service networks before moving the child from an institution to family-based care. Implementing family-based models of childcare should not be a foundation for violating other rights of the child. If a child with disabilities is returning to their biological family or being given to guardianship care or foster care, the child’s right to education, health, and other spheres have to be guaranteed. Such an environment has to be created in which the child will be able to realize, at least, their fundamental rights. Guaranteeing a child’s right to family life is not enough to restrict or ignore that child’s other rights.

5. Recommendations

A precondition for implementing any kind of rights is the creation of an appropriate environment. Hence, for realizing family-based care for children with disabilities, it is necessary to ensure a supportive environment. To create such an environment it is necessary to:

a) Change public perceptions on disabilities: when society is supportive of families with children with disabilities and accepts them on equal principles,

b) Make accessible those services that children with disabilities can use without being isolated from their family environment.

In the past several years, policies aimed at guaranteeing the right to family life for children promise positive trends for the development of foster care for children with disabilities. As a result of this analysis, the following recommendations have been identified to carry out this process more effectively:

Government

1. To develop deinstitutionalization policies within the framework of interdepartmental collaboration by including civil society, NGOs, community service providers, people with disabilities and parents/care providers of children with disabilities. This process requires strong interdepartmental collaboration. International experience has shown that interdepartmental collaboration has made it possible to effectively carry out deinstitutionalization policies.

2. To specifically target children with disabilities in the deinstitutionalization strategy and develop relevant actions and mechanisms to organize their deinstitutionalization. To focus special attention on specialized care institutions as a way to organize family-based care for children with disabilities.

3. To synchronize legal documents regulating the sphere. To initiate action on the deinstitutionalization process of institutions carrying out childcare and take steps toward the development of specialized foster care institutes in strategy plans, specifically in programs on the protection of children’s rights and the social inclusion of children with disabilities.

4. To include on the agenda of the Council on Managing Revisions on Evaluation Systems of the Needs of People with Disabilities the issue of institutions carrying out care for children with disabilities.

5. To realize an in-depth individualized evaluation of the needs of children with disabilities residing in special institutions providing care and social protection and develop an individual care plan for every child as a result of deinstitutionalization.

6. To carry out causative case studies on types of disabilities, channels of placement of these children into institutions, age at which they end up in institutions and by researching other factors. Thus, developing strategies and targeting action plans on preventing the abandonment of children.

7. To expand community-based services, specifically the geography of specialized services, by prioritizing those communities where more children have to be placed due to deinstitutionalization. The biggest lesson from international experience is that the creation of family-based and community-based service networks has to take place before institutions are closed so that the child’s needs receive targeted solutions as soon as they leave these institutions. If not, reinstitutionalization would become a real threat.

8. To set special supervision mechanisms based on the special needs of children with disabilities. Be more sensitive when it comes to supervision, taking into account the presence of the disability, its type, and needs. International experience has shown that the rights of children with disabilities in foster care families are violated more than children without disabilities.

9. To establish qualification and training courses for specialized foster care. This has to be done with special sensitivity and detail by giving them more time in addition to general foster care courses.

10. To reassess the financial compensation given for specialized foster care for children. The amount should be set based on the child’s specific needs and how much is needed to fulfill those needs.

11. To view crisis foster care as an opportunity for childcare while the parents contemplate about abandoning the child at the hospital.

12. To carry out a large awareness campaign on foster care and disabilities, specifically targeting:

- Potential foster parents,

- Youth as potential parents,

- The public: a) to understand the essence and meaning of foster care, to differentiate it from other types of care, b) to be informed about different types of disabilities.

Based on an in-depth evaluation of needs, carry out targeted campaigns on recruiting foster parents for children with special needs (for example, the need for palliative care).

NGOs

- Mobilize resources in those communities where children will end up living as a result of deinstitutionalization.

- In order to provide targeted support to specialized foster families, merge the child’s personal priorities with state policies.

- To raise the level of awareness on specialized foster families in the beneficiary community.

- To support establishing communication between state bodies and those who wish to become foster parents.

Media

- To cover specialized foster care more often, organize educational programs, inform the public about the aim and realization of foster care.

- To maintain a code of ethics on covering children, to portray the utmost sensitivity when covering topics on them in order to not harm the child and other members of the family, taking into account short-term as well as long-term possible consequences.

Donors and other supportive structures and individuals

- In order to organize targeted support, integrate strategies/priorities on the support given to the state and civil society with the deinstitutionalization strategy being developed by the Government.

Thanks to Ani Avetisyan and Susanna Gevorgyan for the research they assisted with for this policy analysis.

This project is funded by the UK Government’s Conflict, Stability and Security Fund.

The opinions expressed are those of the authors’ and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the UK Government.