The Security Context

In July the security configurations for the Republic of Armenia remained consistent, while the situation in Stepanakert exceedingly deteriorated, as the international community and the West’s stabilization efforts insulated Armenia-proper from any egregious actions by Azerbaijan, with Baku subsequently turning its attention to the complete strangulation of Nagorno-Karabakh. The negotiation process was restructured into two tracks, the continuation of the Armenia-Azerbaijan track and attempts at the formulation of a new Stepanakert-Baku track. While the West and Yerevan separated the two tracks, Baku and Russia attempted to amalgamate the two in a continuous and orchestrated process of obstructionism. In this context, the former grouping supports the introduction of international instruments to accommodate the Stepanakert-Baku track, while the latter grouping remains opposed. Thus, initial secret negotiations that were to take place in Bulgaria collapsed when Stepanakert backed out under intense Russian pressure, while the second meeting that was to be held in Bratislava fell through because Baku refused to show up, instead agreeing to the Russian proposal of holding the negotiations in Azerbaijan, an untenable proposal for the Armenians.

Consequently, whereas Armenia and the West sought to give Stepanakert agency through the introduction of a new negotiating track, Baku and Moscow sought to deny this development. Supplementing this denial was the complete blockade of the Lachin Corridor, the attempted discrediting of the International Committee of the Red Cross, and the growing humanitarian crisis in Nagorno-Karabakh. To remedy the pending humanitarian catastrophe, Armenia dispatched 400 tons of aid to the Lachin Corridor, with the objective of negotiating with the Russian contingent to accompany the humanitarian aid to the Armenian population. Azerbaijan’s refusal to allow for the passage of the convoy has been reinforced by the refusal of the Russian peacekeepers to meet with the Armenian side. Conceptually, the Russian presence in the theater of conflict simply acquiesces Azerbaijan’s suffocation of Nagorno-Karabakh, and in more practical terms, Russia maintains access to airlifting supplies to its own troops, but refrains from airlifting basic necessities to the Armenian population. Observing these developments in its totality, and anticipating the congruence of Russo-Azerbaijani interests to amplify the crisis and selectively destabilize the security situation, Armenia must develop and adopt a concept known as “strategic intelligence” into its decision-making and operationalizational capacities.

The pending humanitarian crisis in Nagorno-Karabakh represents a potential security dilemma for Armenia, further amplifying an already-intense security environment that has been somewhat stabilized through diplomacy, the presence of the EU Civilian Mission, and the active engagement of the United States and the European Union in the negotiation process. The deteriorating situation in Nagorno-Karabakh, however, can substantively negate the relative stabilization that has been achieved. Baku’s calculus is to force Yerevan’s hand by creating such an untenable situation in Nagorno-Karabakh that Armenia would have no choice but to use force, thus falling into Azerbaijan’s trap and initiating hostilities. Fully aware of this entrapment, Yerevan has opted to rely on international instruments, intense diplomacy, and reshaping of the broader narrative on the vulnerable Armenian population. While this has produced wide-ranging condemnations from countries such as the Netherlands, Spain, France, Lithuania, Czechia, Slovenia, Cyprus, United Kingdom, the United States, and the European Union, Baku has not only tightened the blockade, but has proceeded to illegally detain and kidnap ethnic Armenians being transported by the ICRC. Finding an alignment of interest in discrediting international organizations, Russia is tacitly abetting Baku’s objectives and thus further deepening the crisis: the policeman in the room is turning a blind eye while the perpetrator keeps torturing the victim. As the security environment that Armenia finds itself in has become exceedingly complex and multi-layered, rearticulation of Armenia’s new security architecture must integrate an important instrument into its national security strategy: strategic intelligence.

Strategic Intelligence

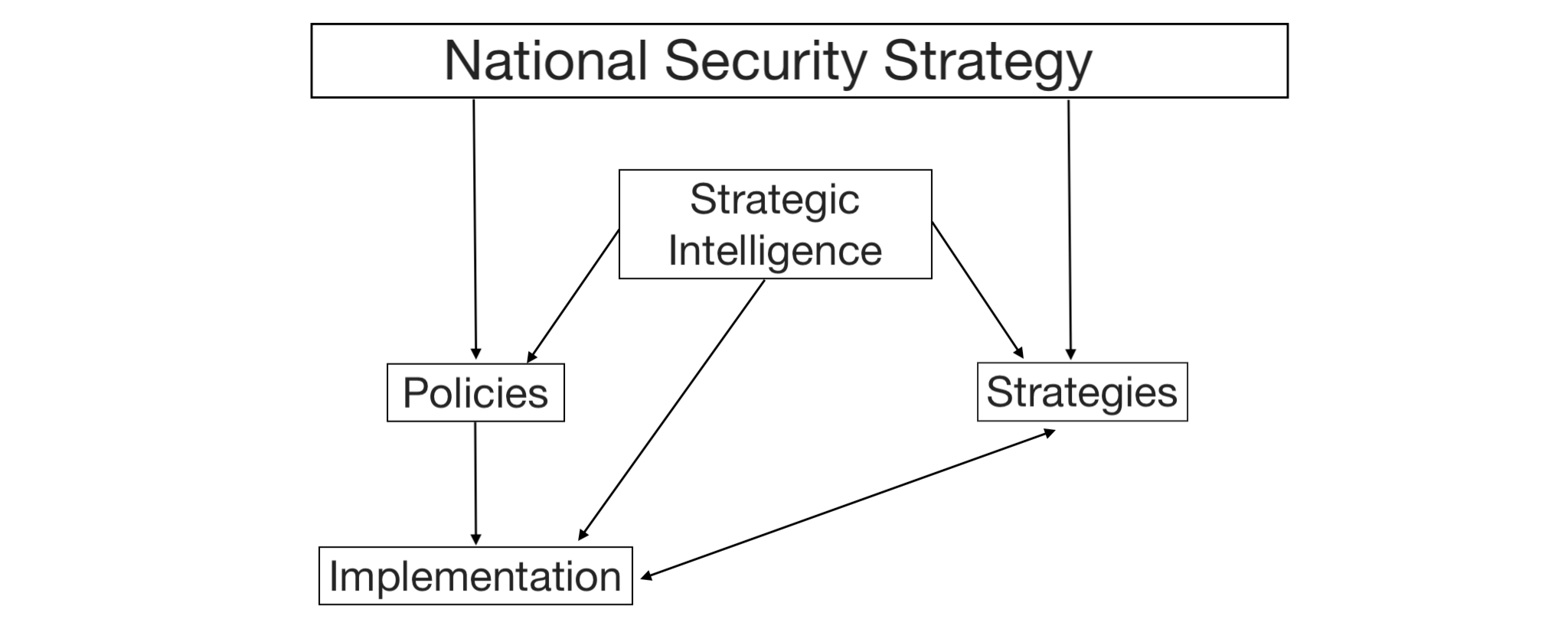

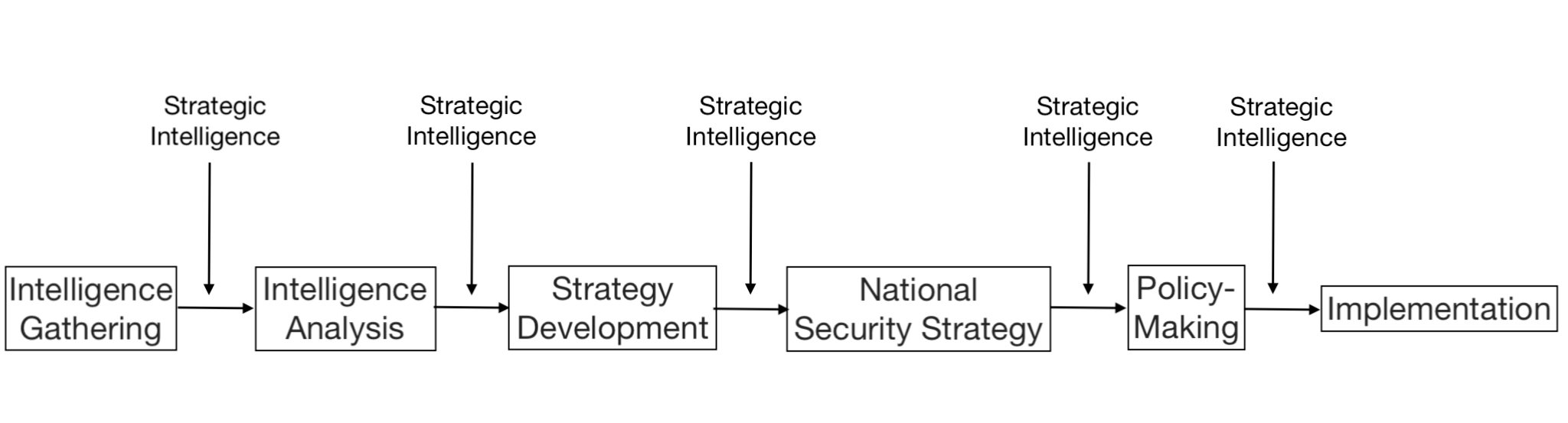

The field of strategic intelligence (STRATINT) is built upon classic intelligence theory, utilizing both academic scholarship and the work of practitioners from the intelligence community to develop a more nuanced and operationalizable instrument in formulating policies specific to national security. Strategic intelligence is primarily defined as intelligence that is required for the formulation of strategy, policy, and the operationalization of military plans at the national and theater of conflict level. In more layman terms, strategic intelligence is qualified as the intelligence needed to create and implement strategy, and more specifically, national security strategy. Conceptually, strategy is not so much a plan but the broader logic driving the plan, and as such, strategy advances a nation’s goals by suggesting methods of organizing and accommodating a wide variety of variables. The complex and multifaceted nature of such variables requires in-depth, surgical knowledge of the phenomenon at hand: hence the necessity of strategic intelligence. Without strategic intelligence, and the systemic orchestration of the variety of variables that shape national strategy, strategy becomes nothing more than an abstract theory. Thus, for national strategy to be concrete, substantive and operationalizable, it requires strategic intelligence.

In Armenia, the term “strategic” has been understood and used interchangeably with the concept of “strategic intelligence,” which suggests a fundamental flaw and misunderstanding of strategy-development. Consequently, the strategic product that has been produced has resulted in enormously detrimental consequences. In this context, not only is Armenia unable to develop a coherent national security strategy, but it also cannot advance the implementation of such a strategy without the application of strategic intelligence. Sadly, Armenian “policy-makers” or “strategists” have never known nor had the training in how to utilize strategic intelligence in the formulation of national security strategy. Rather, intelligence in Armenia’s security apparatus has been viewed as tactical or tangential, as opposed to being strategic and surgical in the development and implementation of policy. In essence, the tactical has been confused and conflated with the strategic, as clearly elucidated by 30 years of Armenia not having a grand strategy nor a vision of a comprehensive national security strategy.

Intelligence, for the most part, has been simply qualified as a necessary resource for the development of military tactics for immediate or specific needs. The notion of using the multitude of complex variables that are inherent to intelligence as an instrument of grand strategy-development has been nonexistent in the thinking and training of Armenia’s security community. The reasons for this are many, ranging from lack of indigenous domestic training, to overreliance on outside partner(s), to the dearth of scholarship or research on intelligence. In essence, since strategic intelligence requires the fusion of both academic scholarship and the knowledge of intelligence operatives, Armenia has a severe deficiency in both. The former is fundamentally nonexistent, while the latter is inherently underdeveloped and has, until recently, been subjected to the informational dominance of a regional hegemon. Relying primarily on open source intelligence, or what the Russians have been willing to share, Armenia’s capacity for developing strategic intelligence has not only been methodically hampered since independence, but it has also been designed to fail. The fact that Armenia has very little capacity for human intelligence (HUMINT) speaks for itself.

Concentrated Surprises and Intelligence Failures

It is an open secret that Armenia had almost no intelligence, or intelligence that was either systematized or operationalizable, during the 2016 Four Day War when Azerbaijan initiated a full-scale attack across the entire Line of Contact with Nagorno-Karabakh, or the 2020 44-Day War, where Azerbaijan fully invaded Nagorno-Karabakh. The complete absence of strategic intelligence left Armenia both relatively blind-sided and fundamentally unprepared with respect to the designs, operational capacities, and strategic objectives of the enemy. In essence, the entirety of the intelligence framework, whatever of it that Armenia had, not only proved to be useless, but even counterproductive, as it gave both incorrect and false predictions and capability assessments. More so, Azerbaijan had far more intelligence and information on Armenia than Armenia had on Azerbaijan. Thus, aside from the hard power asymmetry, there were profound disparities in intelligence capacity, and more specifically, in strategic intelligence. This disadvantage has created severe problems for Armenia in instances of “concentrated” surprises.

Concentrated surprise is the product of a directed effort on the part of an actor determined to prevent an adversary from knowing the scope of its designs and real capabilities by concealment and stratagem in order to gain an advantage. The 2016 Four Day War is a clear example of a concentrated surprise, where strategic intelligence failures on behalf of Armenia failed to anticipate nor cogently foresee an operation of the scale that Azerbaijan undertook. Intelligence failures, in this context, do not happen in a vacuum, but rather, are the byproduct of a small number of strategic intelligence failures culminating in a severe intelligence breakdown, one that catches the entire system off-guard, resulting in detrimental consequences. In this context, a crucial advantage of developing strategic intelligence capabilities, and as such, formulating strategic outputs that can account or, to a large extent, prepare for concentrated surprises, remains crucial to the national security strategy of any country, especially one as vulnerable as Armenia. In this context, the 2020 44-Day War is no different, for as a clear case of concentrated surprise, Azerbaijan unleashed a full-scale invasion of Nagorno-Karabakh, the scope of which Armenia’s intelligence community had very little substantive knowledge. The assumption that an attack by Azerbaijan may happen at any time is not exactly the same as strategic intelligence; rather, did Armenia know that Azerbaijan’s main thrust will be from the south, did Armenia anticipate the scope of aerial dominance that Azerbaijan may potentially establish, did Armenian intelligence know that drones were a fundamental part of Azerbaijan’s strategy, and did knowledge in any of these areas translate into policy shifts, tactical corrections, and strengthening of defensive positions?

Conceptually, each of these questions are attempts at orchestrating the variety of variables into concrete, substantive, and operationalizable strategies. This is the essence of strategic intelligence. That the answer to all of these questions is a hard negative is a crucial indicator that Armenia did not really have much strategic intelligence. Compounding the problem of concentrated surprises and absence of strategic intelligence was Azerbaijan’s incursions and expansion of hybrid warfare tactics into Armenia proper, with the culmination of the Jermuk invasion in September of 2022. That Armenia was relatively better prepared in relation to the previous incursions cannot be denied, but at the same time, this relative increase in strategic intelligence still remained marginal in relation to the problem at hand.

The literature on strategic intelligence failures offers five general explanations, which remain robustly consistent with Armenia’s disastrous intelligence outputs.

1) Failure in the area of intelligence gathering capabilities: Armenia’s lack of sufficient human intelligence, absence of technological espionage capabilities, inadequate utilization of open source intelligence, and three decades of reliance on an external actor for selective intelligence.

2) Noisy information environment: deficiencies in sorting and absorbing data, inability to accurately disentangle complex or ambiguous data, failure to decipher misleading body of information, and systemic limitations in reconciling the large body of contradictions in the information absorbed.

3) Human factor failures: collective failure of intelligence professionals (both analysts and field operatives), failure to correctly identify intelligence targets, and a systemic failure to predict or anticipate scope of concentrated surprise.

4) Organizational difficulties and deficient cooperation: inter-organizational failures in information sharing and coordination; breakdown in communication between structures within the security apparatus as well as between institutions of government; distrust between institutions and institutional inability to collect, process, and operationalize vital intelligence from the theater of conflict.

5) Intelligence-policy relationship: dysfunctional relationship between intelligence structure and policy-makers; disconnect between strategy-development and intelligence capabilities; and absence of a professionalized, capable intelligence community.

Conclusion

That Armenia needs and is in the process of overhauling its intelligence infrastructure should no longer be a subject of contention, but at the same time, important conversations must be interjected into the discourse on security, strategy, and strategic intelligence. A crucial part of strategic intelligence and national security strategy is the development of a comprehensive security doctrine, which is defined by resilience, broad ranging reforms in the security apparatus, and an expansive treatment of the state’s ability to develop threat assessment capabilities. Intelligence has always been a very sensitive subject of conversation, a byproduct of the Soviet security culture and the institutions that were inherited. But sensitivity is not a substitute for indifference, and critical self-reflection is necessary to allow for a rebuilding of the country’s intelligence capabilities.

Examining the Context

As the security environment in Armenia and Artsakh (Nagorno-Karabakh) continues to be critical, Dr. Nerses Kopalyan (UNLV) speaks to EVN Report’s Maria Titizian about the July 2023 Security Report and explains why any rearticulation of Armenia’s new security architecture must integrate strategic intelligence.

EVN Security Report

Strategic Obstructionism and a Potemkin Hegemon

EVN Security Report: June 2023

In this security report, scenario planning is fused with contingency planning to prepare courses of actions and outcomes that may address unexpected situations and mitigate significant impact to Armenia due to the ongoing Russia-Ukraine conflict and its effect upon Russia’s domestic political order.

Read moreMining for Security

EVN Security Report: May 2023

Armenia’s vast mines have never been part of its security architecture, nor has the potential securitization of this sector ever been considered a fundamental cornerstone of building alliances or strategic partnerships. Mining-for-security should not be qualified as a political act, but rather, a fundamental security act, Nerses Kopalyan writes.

Read moreFrozen Conflict Persistence and Strategic Negligence

EVN Security Report: April 2023

Russia’s refusal to either enforce or impartially implement the terms of the November 9 tripartite statement that ended the 2020 Artsakh War has generated a growing cleavage between Armenia and Russia, revealing Moscow’s preference for frozen conflict persistence.

Read moreThe Geopoliticization of Democracy and the Problem of Illiberal Peace

EVN Security Report: March 2023

The region’s security arrangement remains in flux as Azerbaijan amplified its rhetorical aggression and engaged in expansive troop movements and build-up in border areas. Greater Western involvement has deepened the alliance between Azerbaijan and Russia. While Moscow and Baku have established a united front against the West’s presence in the region, Armenia has proceeded to reconfigure its strategic interests, advancing its democracy narrative, while aligning its preferences to the resolution of the conflict with the Western-led stabilization efforts.

Read moreResilience

EVN Security Report: February 2023

Armenia's precarious security situation is compounded by its underdeveloped institutions and infirm infrastructure. For the February security briefing, Nerses Kopalyan writes that in this context, the entirety of Armenia’s social and governmental approach must revolve around building resilience.

Read moreSee all EVN Security Reports here