The evolving situation of Armenia’s security context continues to demonstrate high risk propensity, but relative to the month of September, this risk has marginally diminished. The diplomatization of security, as a stopgap doctrine, has temporarily contributed to the diminishing threat metric, as active diplomatic involvement by the United States and concrete and substantive involvement by the European Union have robustly contributed to current developments. The country’s security dilemma, however, continues to persist, as Azerbaijan’s superior military capacity, the disparity in hard power, and Baku’s capacity to operate from a position of strength mitigate the extent to which Armenia can continue to rely on the doctrine of diplomacy-as-security. The presence of the 40-strong EU Observer Mission, along with America’s direct and indirect involvement in enhancing it’s diplomatization of security doctrine, have created guardrails against the degree of freedom that Azerbaijan has had in initiating interstate militarized disputes. However, these guardrails remain ephemeral, and generally speaking, substantively ineffective in curtailing Azerbaijan’s broader and long-term hybrid warfare strategy. In this context, the security context for the month of October can be better understood as the growing doctrinal competition between Armenia’s implementation of its diplomatization-of-security doctrine against Azerbaijan’s multi-tiered hybrid warfare doctrine. Further, whereas Azerbaijan reserves the capacity to transition from hybrid warfare to actual wide-scale incursions, Armenia’s security architecture remains, for the moment, highly reliant on diplomatic triangulation.

Armenia’s Security Context

The security context for October 2022 was defined by the continued diminishing of Russia’s role as the dominant security actor in the region, with Armenia recognizing the collapse of the Russian-led security architecture, Azerbaijan attempting to establish a reciprocal balance between Russian and Western involvement, and the active presence of the European monitoring mission in Armenia. This has been supplemented by the inclusion of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) into the process, with the OSCE sending a “needs assessment” team to Armenia. These developments remain congruent with two main factors: the continuous attempt by Europe to facilitate a diplomatic solution to the security dilemma and the West’s broader response to Azerbaijan’s tacitly obstructionist behavior. The trigger for the latter was the release of footage showing the extrajudicial execution of unarmed Armenian soldiers by Azerbaijani forces, which is a microcosm and yet a methodical component of Azerbaijan’s implementation of its hybrid warfare strategy. The general response was shock and condemnation by the West, insouciance from Russia, and general indifference from Baku. The collective condemnation of the West remained indicative of a general consensus of understanding vis-a-vis Baku’s overarching objectives, while Russia’s bothsideism dovetailed Azerbaijan’s indifference, reifying the tacit understanding that Russia has abdicated its role as Armenia’s security guarantor.

The growing role of the United States as a contributing actor to Armenia’s security dilemma, and by extension, filling the vacuum left by Russia’s relative marginalization, has been on display on two fronts: securing the release of 17 POWs and deepening of inter-bureaucratic relations between Armenia’s Ministry of Defense and America’s Department of Defense. Since military reforms remain one of the inherent strategic interests with respect to Armenia’s new security architecture, the enhancement of relations between Armenia’s Ministry of Defense and America’s military educational institutions, such as West Point, Army War College, and National Defense University, are crucial to enhancing military science and training for Armenia’s underdeveloped military system. The development of inter-institutional relations continue to be supplemented by the active diplomatic pressure placed by the United States upon Azerbaijan since the wide-scale invasion on September 13, with U.S. Secretary of State Blinken initiating calls with both PM Nikol Pashinyan and President Ilham Aliyev to reconfirm America’s stipulation that Azerbaijan’s attempt to de-diplomatize the process in favor of intensified coercive diplomacy contradicts America’s interests. This position was reaffirmed by Ambassador Michael Carpenter, with further confirmation that the United States supported Armenia’s demands of an OSCE fact-finding mission

America’s pivot towards Armenia has also aligned with the amplification of France’s robust support for Armenia, as the U.S.-France tandem has become the dominant guiding force in rearticulating Europe’s approach to Armenia’s security dilemma. France’s initiation of a European civilian observer mission during the quadrilateral Prague meeting of Macron, Pashinyan, Michel and Aliyev on October 6 was subsequently supported by all 27 EU member states. This was followed by the visit of Isabelle Dumont, the Adviser of the President of France to Armenia, where she met not only the Foreign Minister and the Prime Minister, but also the Defense Minister, where matters specific to Franco-Armenian defense cooperation was discussed. Subsequently, Head of the NATO Liaison Office in Georgia, Alexander Vinnikov, also visited Armenia, meeting First Deputy Foreign Minister Paruyr Hovhannisyan and Secretary of the Security Council Armen Grigoryan to enhance and deepen cooperation with NATO on military reforms in Armenia. This was topped off by a U.S. Congressional delegation comprised of the House Democracy Partnership, a bipartisan group of House Members whose visit was designed to both highlight and enhance Armenia’s democratization, while also displaying robust criticism against Azerbaijan’s behavior since September. Further confirming America’s pivot towards Armenia, Chair of the delegation noted the willingness of the U.S. to engage in bilateral and multilateral arrangements in diplomatic support of Armenia’s security architecture.

The support of the United States and Europe, and specifically of France, in the enhancement of Armenia’s diplomatization-of-security doctrine has faced intense criticism from Russia, as Moscow has viewed the American pivot and the U.S.-France tandem to be an infringement into its traditional sphere of influence. At the doctrinal level, the collapse of Armenia’s security architecture is secondary for Russia, for its alignment with Azerbaijan mitigates its loss of soft power in Armenia, while Armenia’s inherent state of weakness reconfirms Russia’s assumption that Armenia has nowhere else to go. The West’s newfound support for Armenia’s security dilemma has punctured Russia’s new South Caucasus policy, for it has not only led to the diminishing of Russian influence in Armenia, but has also weakened Russia’s position with Azerbaijan, while also inviting America and Europe to fill the Russian vacuum. In essence, the collapse of Armenia’s Russian-led security architecture also led to the collapse of Armenia’s dependency structure, which Russia had designed to consolidate Armenia’s status as a satellite. The puncturing of the dependency structure has reconfigured Russia’s status as a weakened regional hegemon, for it has resulted in the disintegration of its regional sphere of influence. Its influence over Azerbaijan has become conditional and even reciprocal, while its influence over Armenia has become incoherent and dysfunctional. The result has been the physical presence of European observers within Armenia proper, the absence of a Russian voice to the process, and the methodical seclusion of Russia from the negotiating process.

Russia’s response to these developments have confirmed three things for Armenia: 1) Russia continues to be indifferent to Armenia’s security dilemma, thus reifying the collapse of the Russo-Armenian security arrangement; 2) Russia has realigned its interests with Azerbaijan, as Baku has joined Russia in criticizing France, refusing to allow European observers into its territory, and crediting Russia, not the United States, for securing the September ceasefire; and 3) Russia has mirrored European activities by suggesting a CSTO observer mission, reinitiating meeting of foreign ministers, and hosting a meeting between the three heads of state at the end of the month. From the lens of Armenia’s security architecture, none of the initiatives proposed by Russia contribute to the strengthening of Armenia’s capabilities, but rather, designate more agency to Baku, while attempting to reestablish, at Armenia’s detriment, the fractured dependency structure.

Iran’s Conditional Posturing

Iran’s geopolitical posturing and its concerns specific to Armenia’s security situation is driven primarily by Iran’s fear of physical isolation. In the wide set of official statements released by Tehran, they have been adamant that the alteration of regional borders remains a red line, a presupposition that entails any threats to Iran’s access to its north, or any such access being controlled by Azerbaijan, will elicit a militarized response. Iran’s more acute concern remains the North-South transit route through Armenia, and the fear that any disruption to this route will be extremely harmful to Tehran’s strategic and commercial interests. Contextually, Iran is not so much concerned about Armenia’s security architecture, but rather, its access through Armenia being an extension of Iran’s own security architecture. Noting the state of relations between Iran and Azerbaijan, Baku’s control over Iran’s access to its north will exponentially decrease Tehran’s regional influence, while also enhancing Baku’s leverage over Iran. Such a development remains a non-negotiable red line for Tehran.

Prioritizing the factors that define Iran’s strategic interests, Tehran has formulated a set of mechanisms to mitigate and delimit the possibility of its red lines being violated by Azerbaijan. First, it opened a consulate in the city of Kapan in Armenia’s Syunik region as both a symbolic move as well as a concrete form of action that demonstrates Iran’s commitment to deterring any violations of its set red lines. Further, this was led by a large delegation headed by its Foreign Minister, a move designed to demonstrate Iran’s unequivocal support for Armenia’s territorial integrity. Second, it initiated large scale military exercises on the border with Azerbaijan, engaging in both a massive show of force as well as undertaking behavior that bordered on brinkmanship. The nature of these activities, however, should be qualified more within the configurations of Iran-Azerbaijan relations, as opposed to pressupposing such developments as an enhancement of Armenia’s security architecture. Namely, Iran’s security concerns are not so much defined by Armenia’s security concerns, but rather, by Iran’s objective of limiting the expansion of Azerbaijan’s regional power projection. In this context, Iran cannot, at this point, be considered a contributing factor to Armenia’s security architecture. Iran’s posture remains conditional: as long as its northern route remains untouched, Armenia’s security dilemma remains outside of Iran’s purview.

Armenia’s security policies, and the multilayered processes that inform and compose the overarching doctrines that shape the country’s defense architecture, remain one of the most vital, yet under-reported and under-studied areas of social, political and institutional importance. Limited public information on security policies and expert-driven inquiries into the development, implementation and implications of such policies, has contributed to a culture of confusion and uncertainty. To this end, EVN Report has launched a monthly security briefing, providing data-driven, in-depth analysis of the country’s monthly security situation by Dr. Nerses Kopalyan.

Examining the Context: EVN Security Report, October 2022

EVN Report’s Editor-in-Chief Maria Titizian speaks with political scientist and international security expert Dr. Nerses Kopalyan, author of the monthly series “EVN Security Report”.

EVN Security Report: September 2022

Armenia’s security situation remains precarious, as Azerbaijan has exponentially increased its use of interstate conflict mechanisms, undertaking both large-scale invasions as well as incrementally utilizing hybrid warfare to justify violations of the ceasefire.

Read moreAbout the author

Dr. Nerses Kopalyan is an Associate Professor-in-Residence of Political Science at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. His fields of specialization include international security, geopolitics, political theory, and philosophy of science. He has conducted extensive research on polarity, superpower relations, and security studies. He is the author of “World Political Systems After Polarity” (Routledge, 2017), the co-author of “Sex, Power, and Politics” (Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), and co-author of “Latinos in Nevada: A Political, Social, and Economic Profile” (2021, Nevada University Press). His current research and academic publication concentrate on geopolitical and great power relations within Eurasia, with specific emphasis on democratic breakthroughs within authoritarian orbits. He has conducted extensive field work in Armenia on the country’s security architecture and its democratization process. He has authored several policy papers for the Government of Armenia and served as voluntary advisor to various state institutions. Dr. Kopalyan is also a regular contributor to EVN Report.

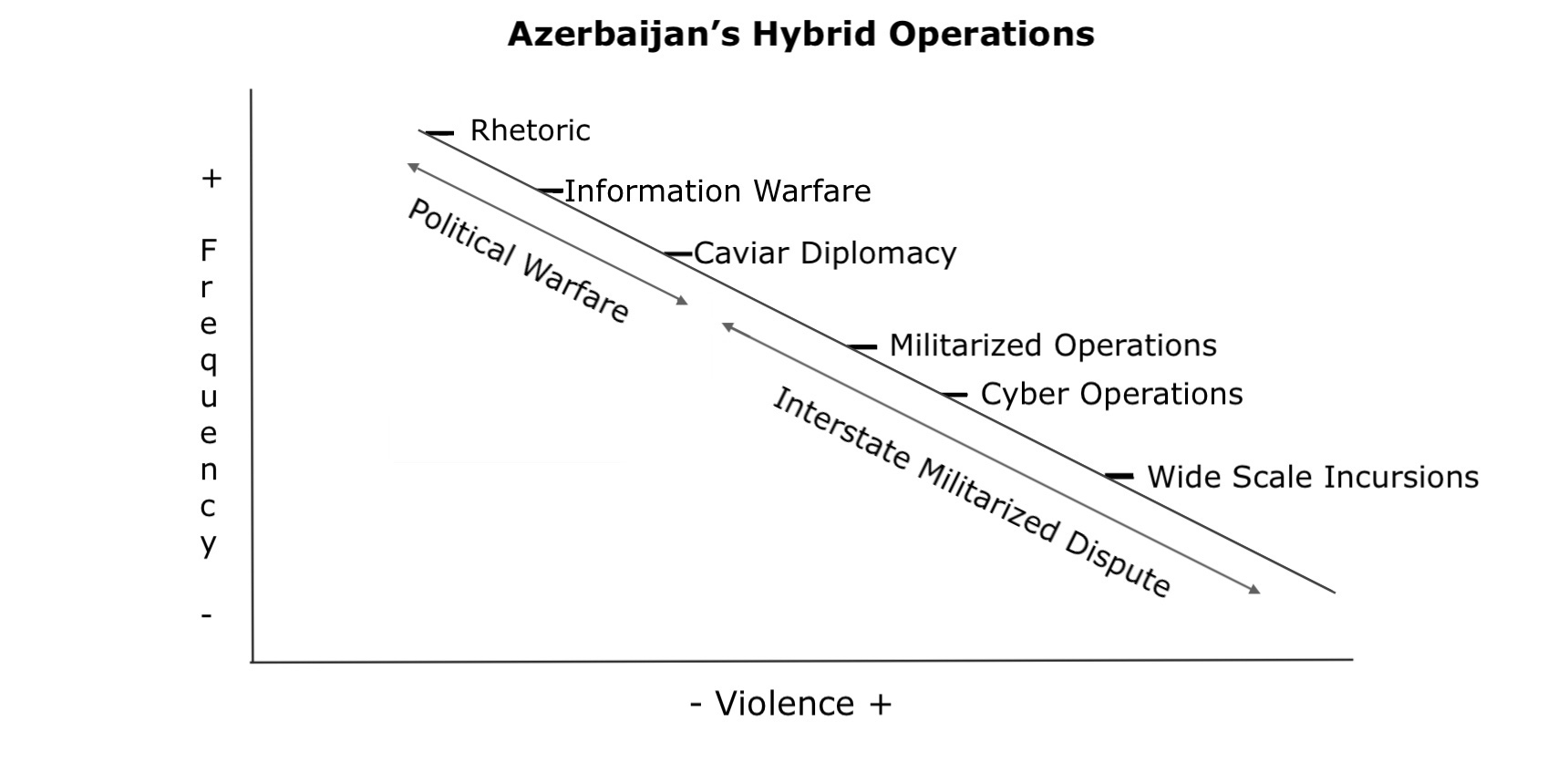

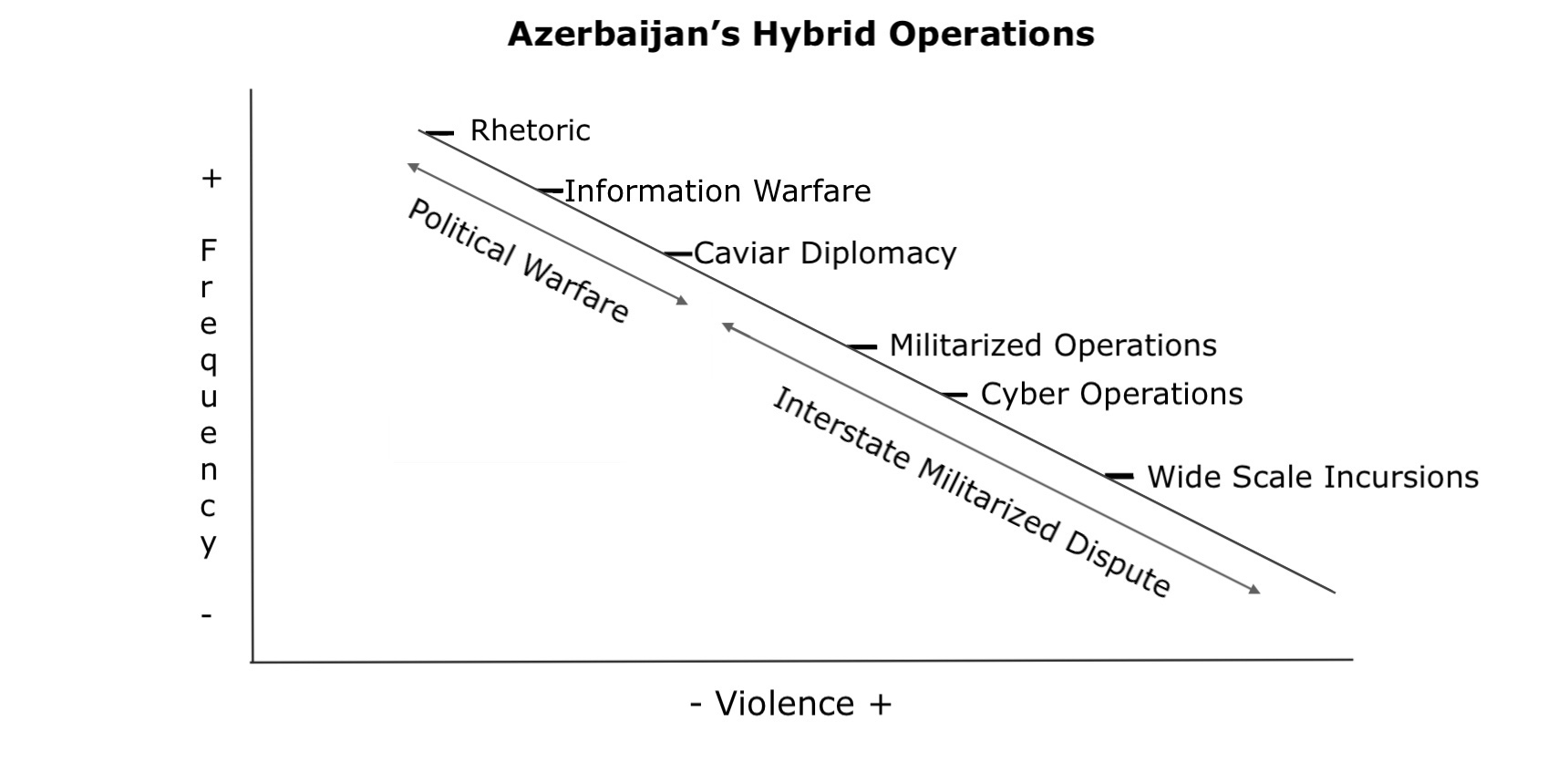

Hybrid Warfare and the Asymmetrical Phenomenon

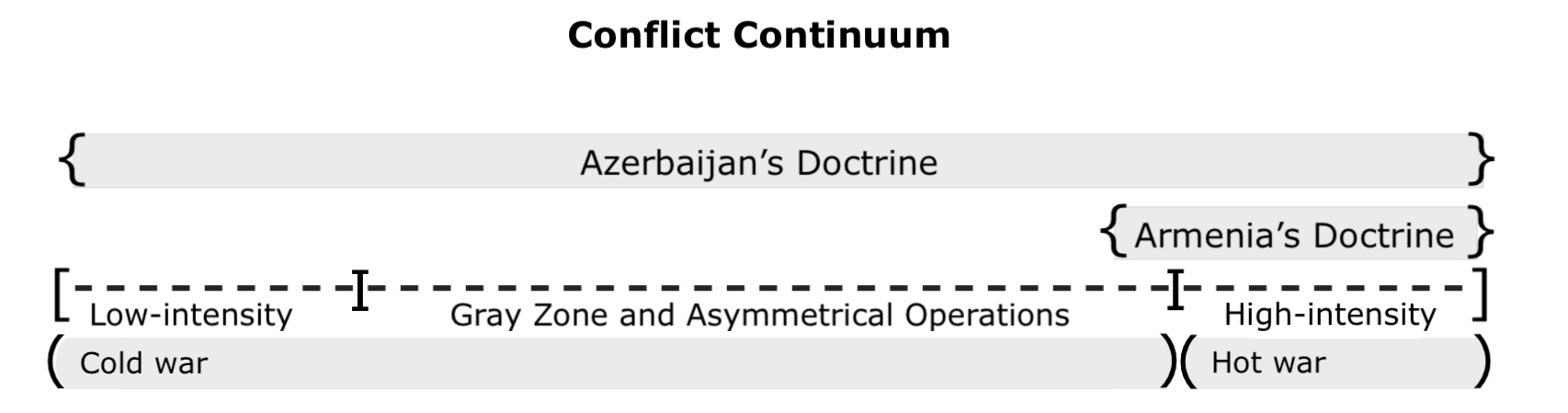

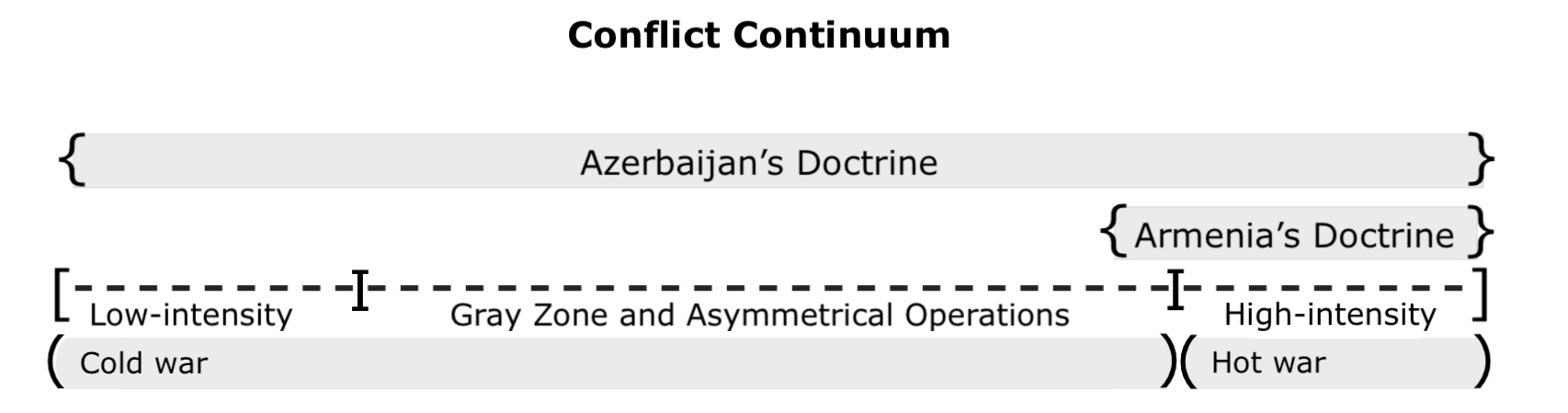

The conceptual dichotomy between peace and war, as far as Armenia’s security situation is concerned, rests on a general misunderstanding of what constitutes peace and what constitutes war. As the prevailing body of literature on hybrid warfare denotes, asymmetrical operations, and gray zone tactics demonstrate, peace, definitionally, has become a relative concept and binary thinking about peace is no longer applicable. In essence, unless peace is qualified as the absence of large-scale, traditional warfare, the concept remains elusive and inapplicable to the security arrangement of the South Caucasus. Considering the 10 year trajectory of Azerbaijan’s grand strategy leading up to the 2020 Artsakh War, a continuity of hybrid warfare and gray zone tactics defined a period falsely assumed as peaceful. In the realm of the asymmetrical phenomena that defines modern warfare, the notion of peace has no substantive meaning. Rather, developments and contextual understanding of security situations must be understood on a continuum: low-intensity hybrid warfare to high-intensity interstate militarized disputes. To use the outdated lexicon, Armenia is and in the near future will be in a perpetual state of “cold” war with Azerbaijan, regardless of formal peace arrangements, with the fluctuating probability of cold war configurations flaring up into “hot” war and full-scale conflict.

Since 1994, Armenia’s security architecture was designed to address the dynamics of full-scale conflict, with exaggerated reliance of Russia, absence of asymmetrical or hybrid capabilities, and a fundamental misunderstanding of Azerbaijan’s well-developed grand strategy. From 2010 to 2020, Azerbaijan diversified its military doctrine by methodically enhancing its hybrid and asymmetrical warfare capabilities, while Armenia doubled-down on an outdated military stratagem: dependence on a guarantor and preserving the Sovietized status quo of its military system. The post-2020 period has not only observed the further enhancement of Azerbaijan’s hybrid capabilities, but also a very well-developed synergy between transitioning from low-intensity hybrid warfare to high-intensity milatized activity. In essence, Azerbaijan has mastered the continuum, while Armenia is still in the process of understanding the continuum. Armenia’s security architecture, at this current point, seeks to mitigate Azerbaijan’s ability of easily and robustly navigating the continuum. This entails two developing, yet nascent, approaches: developing deterrence capabilities (both diplomatic and hard power) to mitigate Azerbaijan’s capacity for high-intensity militarized activities, and de-hybridization. The diplomatization of security has been utilized to temporarily address the former. But in the case of the latter, Armenia’s security architecture faces a severe deficiency.

Perpetrators of hybrid warfare, qualified in the literature as an “antagonistic state,” is typically an authoritarian government or dictatorship that has little inhibition against aggressive behavior and that possesses highly centralized, rapid and coordinated decision-making structures. Through hybrid warfare antagonistic states aim to achieve outcomes without a full-scale war, as they aim to disrupt, undermine, and damage a target country’s political system, defensive capabilities, and social cohesion through a combination of violence, subversion, manipulation, and dissemination of misinformation. In this context, Azerbaijan does not only target Armenian combatants, but also targets Armenia’s political system and its broader society. In the conflict continuum, Azerbaijan utilizes a multitude of instruments of power, with an emphasis on threats, orchestrated misinformation, and militarized operations. Yet these instruments operate below the threshold of open war, thus fluctuating between false flag operations, intermittent use of small arms for cross-border clashes, to actual incursions and localized violence. The intensity of these activities, and the fluctuations in the magnitude of violence, remains commensurate with the broader hybrid doctrine: achievement of objectives without passing the threshold of open war. Contextually, from 2010 to the present, Azerbaijan’s security doctrine has relied more on asymmetrical warfare and enhancement of hybrid capabilities than open warfare: the open war threshold was only met in 2020. In essence, the synergy between hybrid capabilities and open war, the methodical transition from low-intensity to high-intensity conflict, are precisely the qualifiers that better explain Baku’s military doctrine. As such, diplomatization of security, for example, has functional coherence if Azerbaijan seeks to engage in high-intensity operations. But the doctrine has no effect upon the rest of the activities that Azerbaijan undertakes within the continuum.

The central features of Azerbaijan’s hybrid warfare strategy that Armenia’s security architecture must account for are as follows:

- Multidimensionalism

- Coordination and Synchronization

- Integration and Strategic Objectives

- Orchestrated Policy of Deception

- Exploitation of the Boundary Between War and Peace

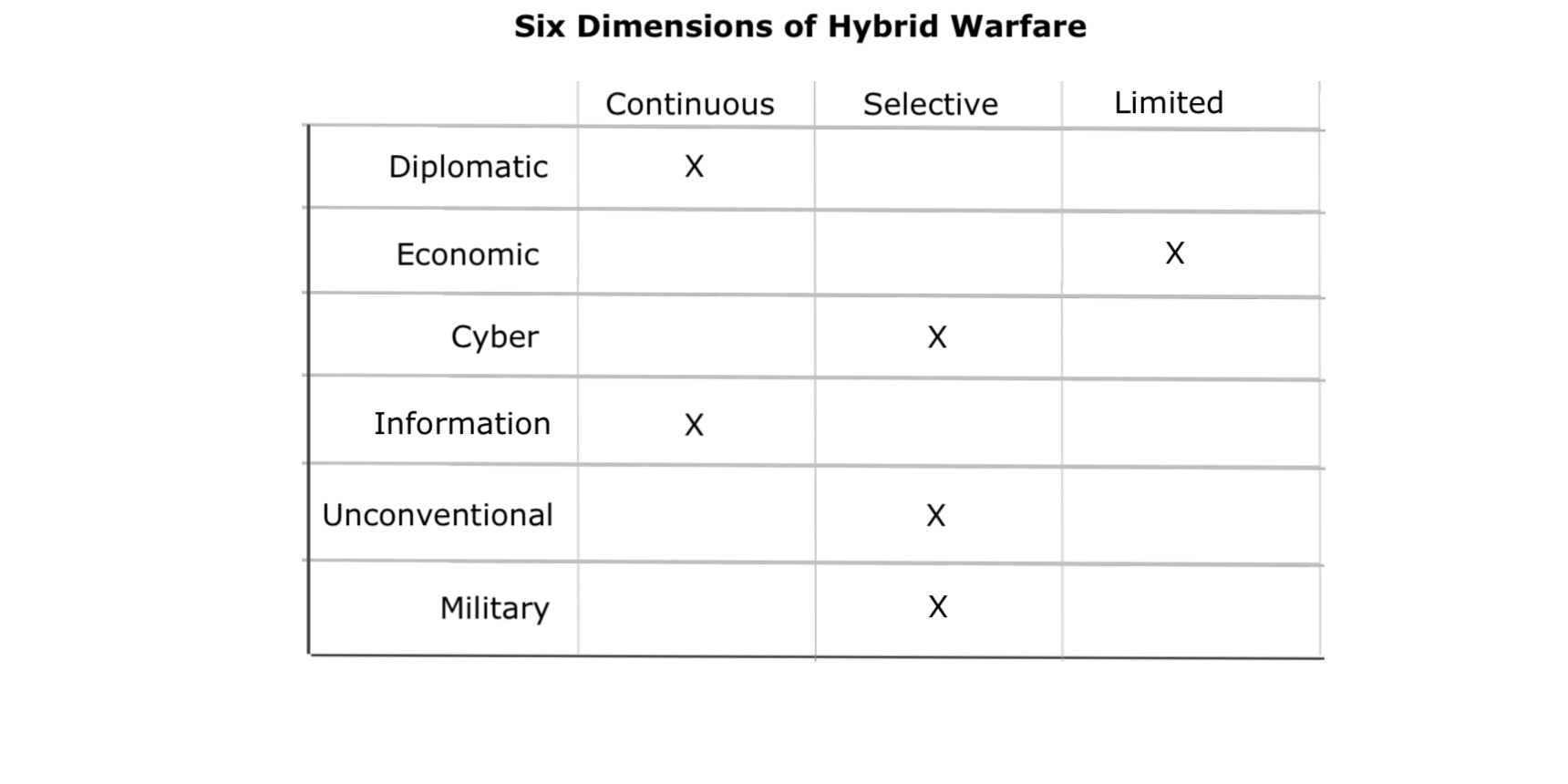

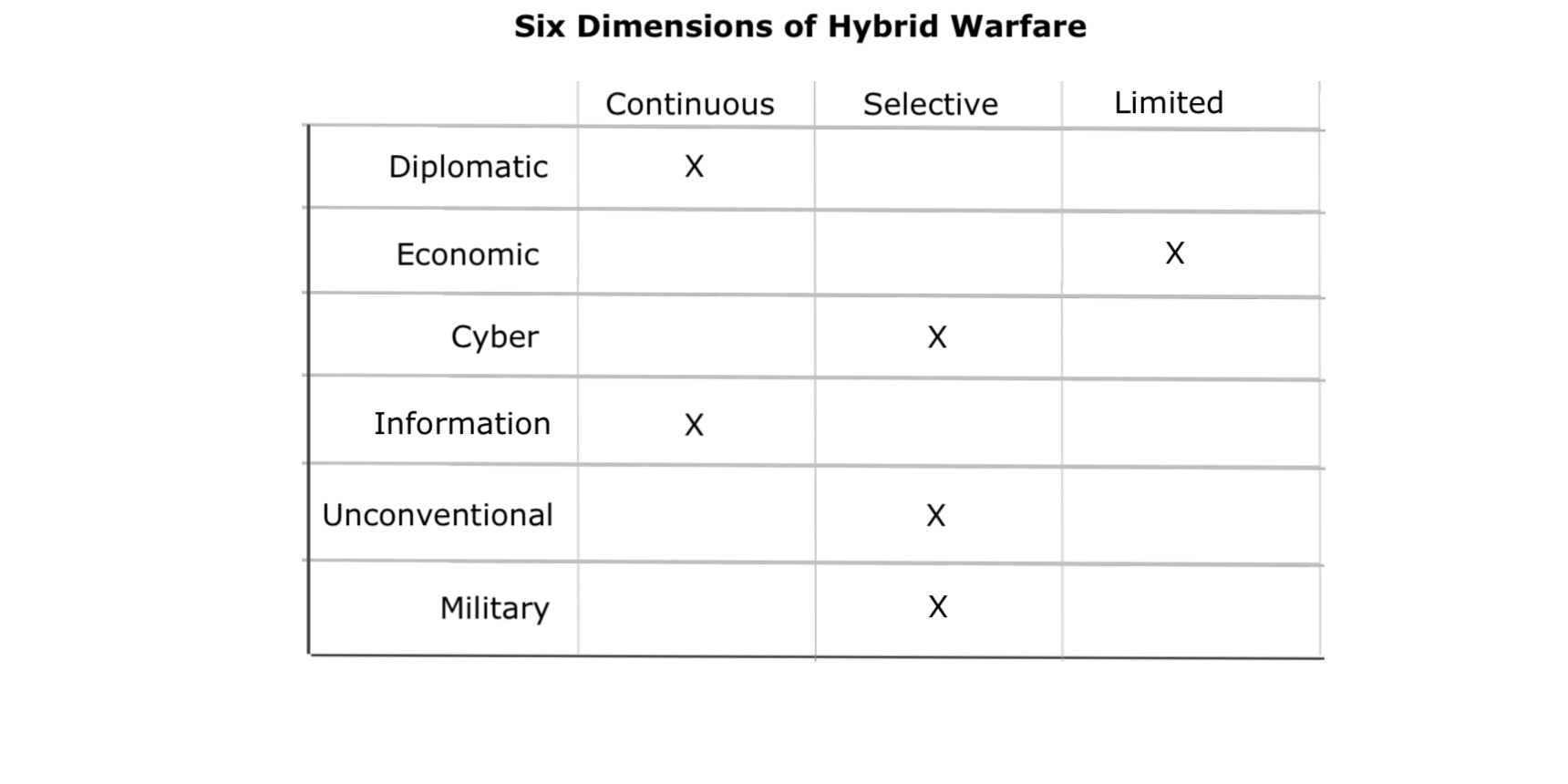

These five features are operationalized through six dimensions:

- Diplomacy

- Economy

- Cyber (technology)

- Information and Influence Operations

- Unconventional Tactics

- Militarized Disputes

Fundamentally, Azerbaijan’s hybrid warfare doctrine utilizes the five features in its operationalization of the six dimensions. Thus, diplomatic, economic, technological, informational, and unconventional tactics all utilize multidimensionalism, coordination and synchronization, integration with strategic objectives, broad policy of deception, and the methodical exploitation of the boundaries of war and peace. These asymmetrical tactics are collectively operationalized to support, define, and justify the fluctuations in the intensity of conflict that Azerbaijan decides to undertake. The coordination and synchronization of messaging by its entire Foreign Ministry system, for example, is integrated with the operational output of its militarized activities, while at the same time troll farms and social media operatives are integrated to proliferate misinformation and implement a broader policy of deception. The multidimensionalism of this multi-institutional approach and the synergy between the country’s diplomatic, economic, informational, technological, and military structures in the operationalization of hybrid objectives, or in response to international criticism, is precisely designed to incapacitate and overwhelm Armenia’s defense and security capabilities. To this end, while Armenia’s diplomatization-of-security doctrine may at some level mitigate the sixth dimension of Azerbaijan’s warfare doctrine—militarized disputes—it cannot cogently address the remaining five dimensions.

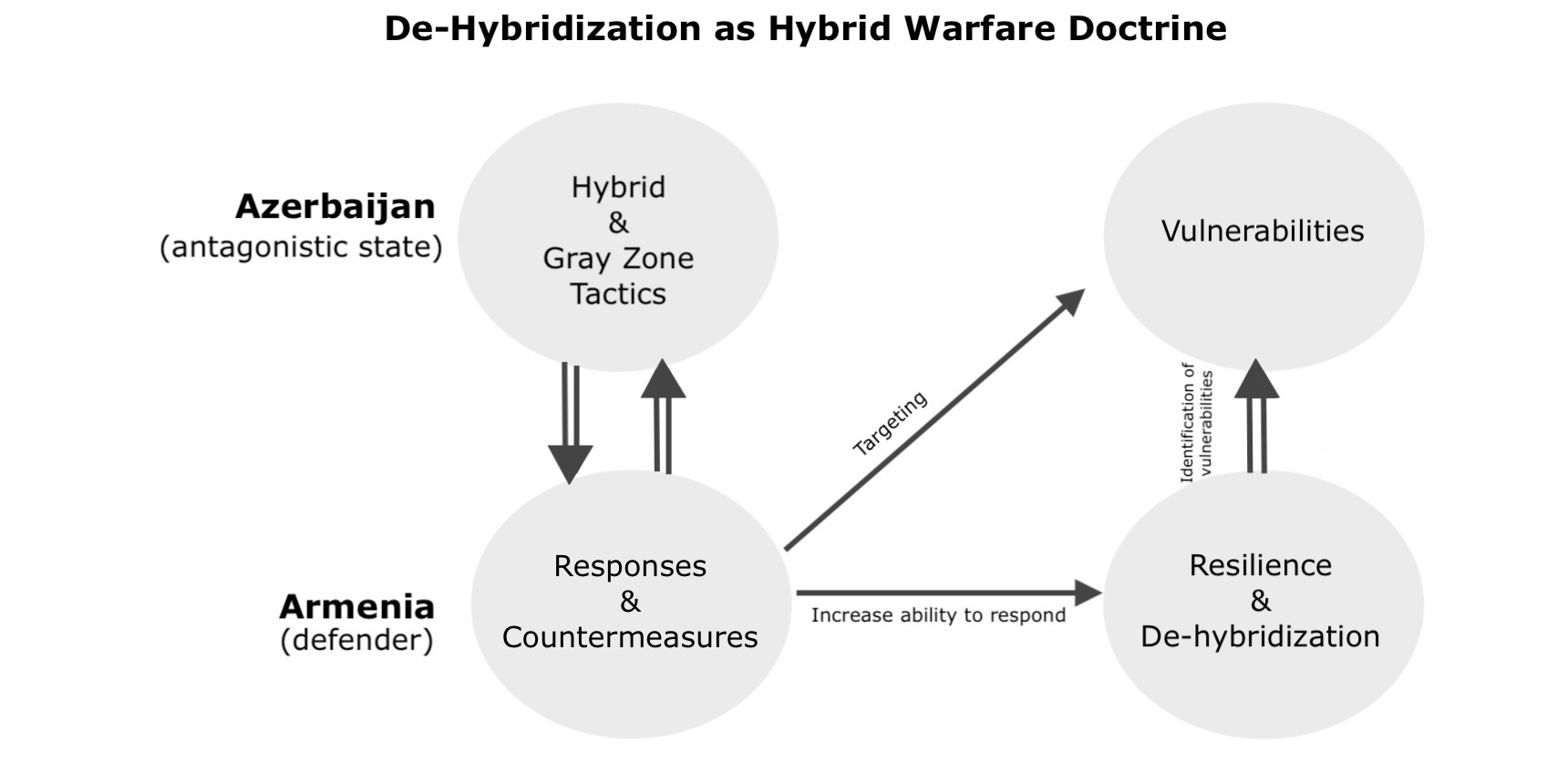

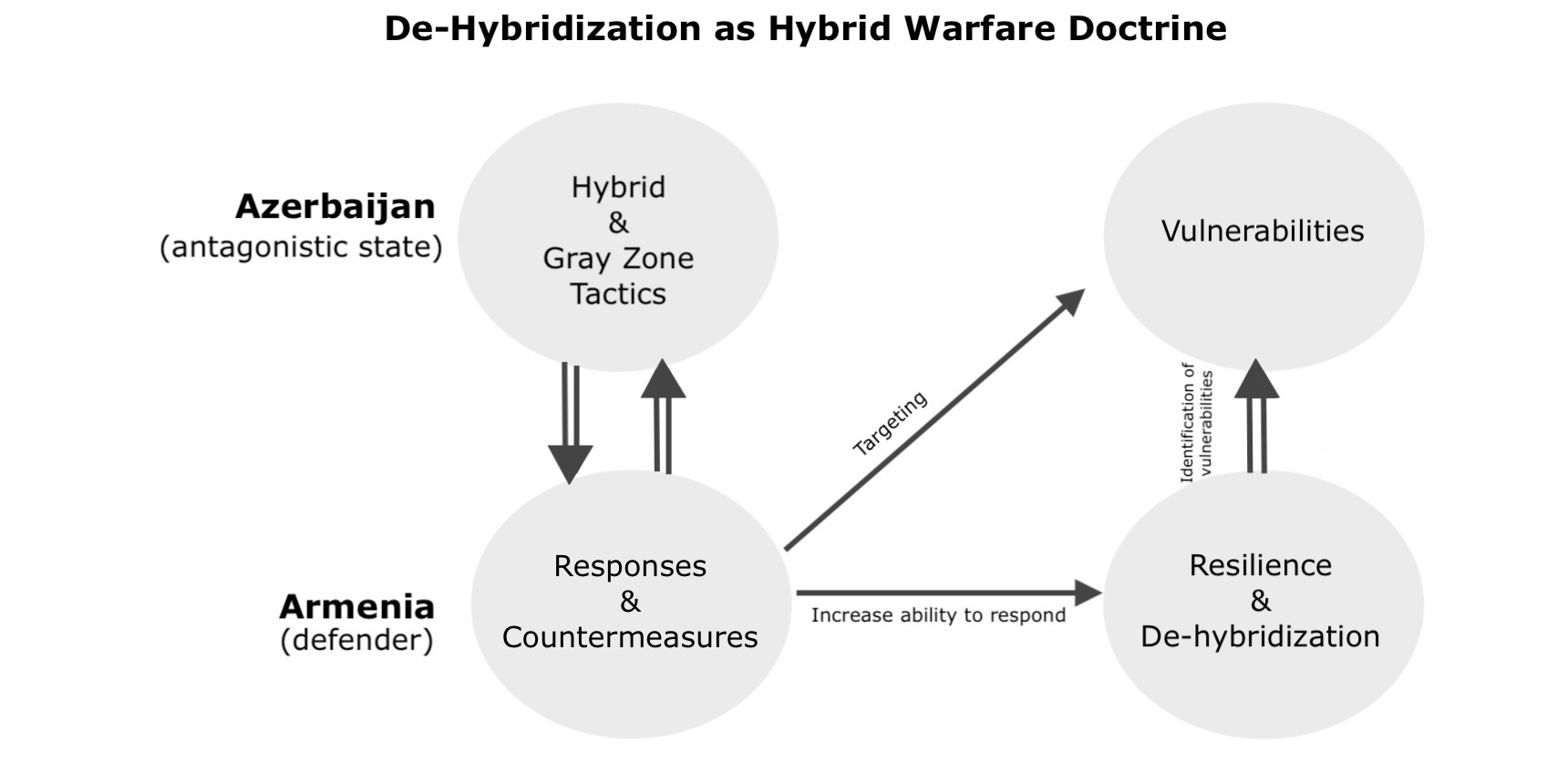

The objective of Armenia’s post-Russia security architecture, in this light, is to develop a hybrid warfare doctrine that accounts for five of the six dimensions of Azerbaijan’s strategy that Armenia currently struggles to confront. Considering the power disparity between the two countries, this power disparity is not only specific to hard military power, but also to hybrid capabilities. In this context, Armenia’s security doctrine also seeks to address asymmetrical warfare through an understanding of this very asymmetry. The concept of de-hybridization refers to this precise process: building resilience against the antagonistic state’s abilities by engaging in deterrence by denial. The objective is not to counter-attack or engage in reciprocal acts of hybrid warfare, but rather, to alter the scope of asymmetry and to change the modality of gray zone tactics: Armenia should not “hit back,” but rather, develop resilience capabilities where Azerbaijan’s hybrid dimensions are rendered ineffective. Thus, de-hybridization, in this case, is not about deterrence-as-punishment, but rather, as noted, deterrence by denial.

As the precariousness of Armenia’s security situation continues, and as Azerbaijan refines and improves its hybrid capabilities, fully understanding that large-scale, open war may not be in its strategic interests considering the international fall out, Armenia’s security architecture must confront the broad continuum of hybridity. Between diplomatization of security and de-hybridization, Armenia’s security architecture can better articulate and develop a security doctrine that is capable of confronting the threats posed by Azerbaijan. Being at a disadvantage, and exploiting that disadvantage, is the difference between understanding asymmetrical warfare and being its victim. Azerbaijan has immense hybrid capabilities, but in the face of de-hybridization, it will be forced to completely re-develop its doctrine. That, in of itself, is deterrence by denial.

Thank you Dr Kopalyan for these reports.I hope these become mandatory readings for all cabinet/parliament members in Armenia. Armenia can not begin to have a grand strategy until it can clearly analyze what the current situation is that it is facing.

A sobering analysis of the breakdown in the Armenia -Russia security arrangement. The failure of the Armenian foreign policy and defense establishment to anticipate the changes in the Russia/Turkey/Azerbaijan tandem is worth analyzing in another article, although it is still hard to fathom in light of the 1915 genocide. One should be careful not to get too excited by all the visits and attention from the US, France , EU and OSCE who promise to replace the vacuum created by Russia’s absence. During the period of 1896-1918 there were several European consulates in Armenia but none of them really helped during the genocide except to “observe”. Armenia needs significant military hard power to counter Azeri- Turkish invasion.