The security context for the month of November demonstrated observable decline for Armenia, as Azerbaijan, frustrated by the success of Armenia’s diplomatization-of-security policy, intensified and amplified its hybrid warfare activities, attempting to neutralize Armenia’s growing attempts at the diplomatization of its deterrence capabilities.

Dismayed by the growing Western support for Armenia since the September 13 invasion, and facing a growing behind-the-scenes coalition of Western diplomatic pressure, Baku is reverting to the hybridization of coercive diplomacy to dilute the effects of Western support for Armenia. Baku’s burgeoning anti-Westernism is coalescing with its pro-Russian posturing, as Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev fears being triangulated by Western pressure. With Russia’s artificial neutrality a foregone conclusion, as well as the CSTO’s irrelevance as a security coalition, Baku feels emboldened in intensifying the coercive mechanisms of its hybrid capabilities. Since gray zone tactics are designed to intensify interstate militarized disputes without initiating wide-scale war, it offers Baku culpable deniability in the face of Western pressure. At the same time, this intensifies the high-risk propensity for Armenia in the domain of losses, as it amplifies the public’s apprehensiveness, while degrading the country’s security situation due to uncertainty. In all such configurations, Yerevan understands that Baku reserves the ability to initiate full-scale war, thus exponentially diminishing Armenia’s security environment. At the same time, to mitigate a severe Western backlash, Baku is reverting to initiating localized operations against Nagorno-Karabakh/Artsakh. In essence, Azerbaijan is diversifying its hybrid operations, with interstate operations against Armenia and “intrastate” operations against Artsakh.

Armenia’s Security Context

November began with the failure of the trilateral meeting in Sochi, as the Russian-led negotiations produced nothing of substance, but rather contributed to the hardening of Azerbaijan’s posture, with the latter seeking to negate the Prague agreements as well as refusing to discuss the expansion of the Russian peacekeeping contingent in Artsakh. Russia’s position of prolonging the determination on the status of Nagorno-Karabakh appears on the surface to be aligned with Armenia’s preferences, but with the collapse of Russia’s role as security guarantor, this posture actually induces Azerbaijan to increase threats against Armenia and Artsakh. Inherently, this no longer becomes about the status of Artsakh but rather the methodical prolonging of instability, which benefits Azerbaijan considering the power disparity facing Armenia.

Armenia’s diplomatization of its deterrence capabilities continued with substantive reliance on the diplomatization of its security, as American judicious involvement and the presence of the European Union’s Monitoring Mission have served as mechanisms to deter Baku’s aggression. The United States hosted the foreign ministers of Armenia and Azerbaijan on November 7, with Secretary of State Blinken reinforcing the continuation of the negotiations process, and actively following up with both sides a week after the Washington meeting. This was supplemented by France’s robust support for Armenia, with Foreign Minister Mirzoyan visiting Paris on November 11 and French Foreign Minister Catherine Colonna confirming support for the Prague agreements as well as the presence of the EU Observation Mission in Armenia. Subsequently, France’s Senate adopted a resolution calling for sanctions against Azerbaijan and demanding the withdrawal of its troops from Armenia, further enhancing Armenia’s reliance on French and European diplomatic pressure. These developments were buttressed by Prime Minister Pashinyan’s attendance at the 18th summit of the International Organization of La Francophonie, where he received strong support from French President Macron and Canadian Prime Minister Trudeau.

Azerbaijan’s attempt to counter Armenia’s diplomatization of its security dilemma has relied on three pillars: intensifying aggressive and threatening rhetoric, amplifying hybrid operations, and obstructing the negotiation process as well as constructive attempts at mediation. Azerbaijan has amplified its hybrid operations by continuously targeting, on a daily basis, Armenian military positions within Armenia proper, while at the same time selectively targeting civilians and farmers in Artsakh. The daily violations of the ceasefire are designed to both destabilize the temporary lull in fighting as well as to hinder and humiliate the work of the European Observer Mission. Baku has reinforced the amplification of its hybridized military activities by aligning it with its obstruction of the negotiation process, as Aliyev has laid doubt on the Prague agreements and subsequently canceled the December 7 talks that were to be held in Brussels. Baku’s attempts to disrupt Armenia’s diplomatization of its deterrence capabilities found a degree of support at the CSTO summit held in Yerevan on November 23, as Armenia’s military decoupling with the Russian-led security alliance was observed. Armenia’s rigid critique of the CSTO, the CSTO’s refusal to condemn Azerbaijan, and the further alignment of several CSTO members with Azerbaijan, reaffirmed the collapse of the Russian-led security architecture of the last 30 years.

Deterrence by Denial and the Failure of Extended Deterrence

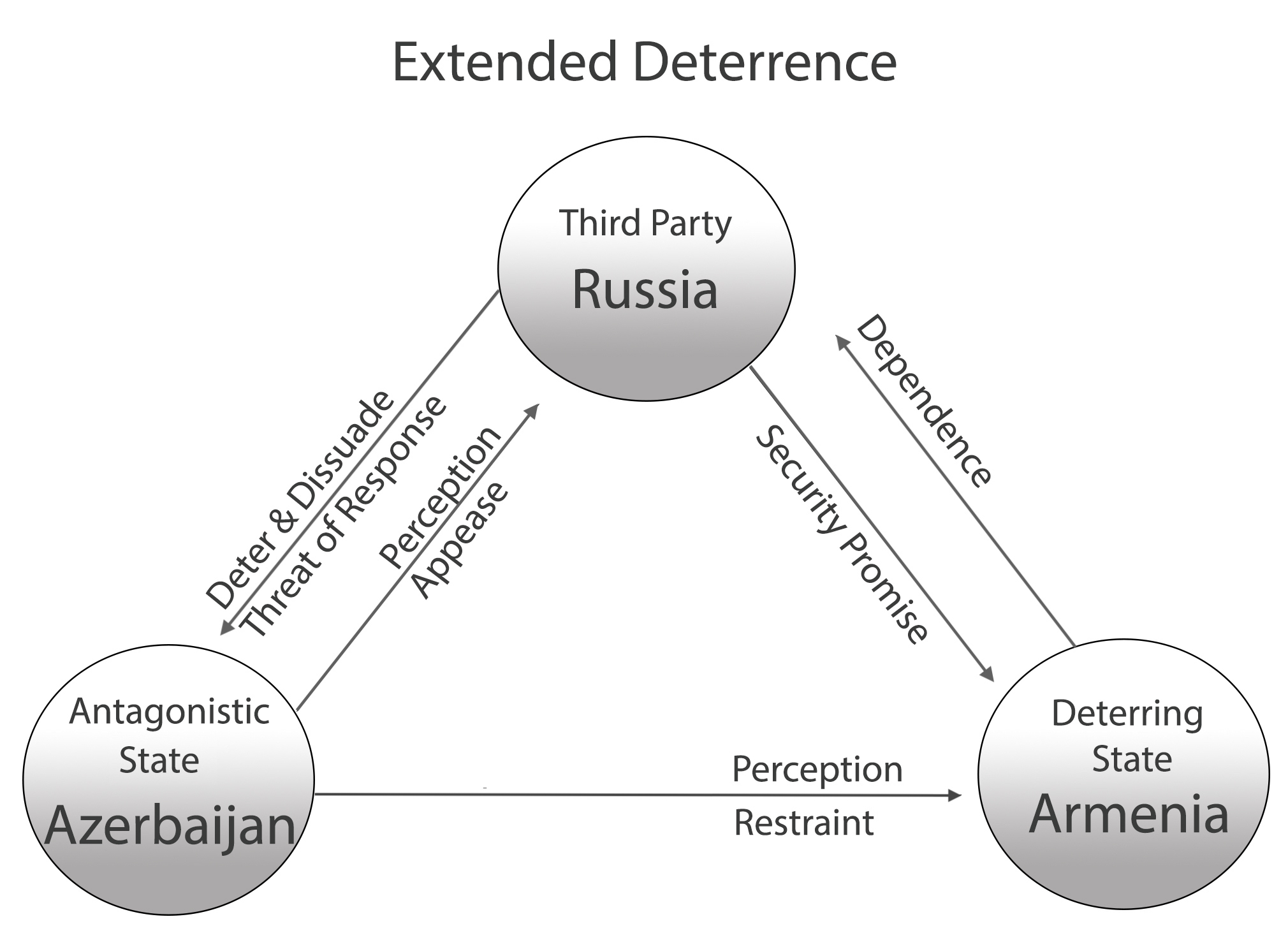

An inherent component of deterrence and dissuasion is defined by the effort to shape the thinking of the antagonistic state. Deterrence against Azerbaijan, for example, cannot be defined through the perspective of Armenia and a simple focus on taking actions that will increase the costs and risks for Azerbaijan. Any deterrence strategy designed to prevent aggression from an antagonistic state must proceed with an assessment of the interests, objectives, motives, and imperatives of the aggressor. Consequently, deterrence strategy must directly affect the perceptions of the antagonistic state. For over 25 years, Armenia’s security architecture was defined by a concept qualified as “extended deterrence.” Extended deterrence entails dissuading and discouraging attacks by relying on a third party, such as an ally or a partner.[1] Armenia’s extended deterrence was squarely dependent on Russia, with the objective of shaping a singular perception in Baku: any attack upon Armenia proper will elicit a Russian response. Reinforcing extended deterrence, however, necessitates taking steps to convince the antagonistic state that the third party defender will unequivocally respond to an attack. Russia’s refusal to respond in the face of Azerbaijan’s attacks directly altered Baku’s perceptions: Armenia’s extended deterrence strategy had either collapsed or had never existed. In essence, the perception that would have dissuaded and deterred aggression was alleviated: the third party defender was nonexistent.

The perception in Baku, in this context, is driven by the understanding that Armenia is a weak defensive state who’s corrupt military system was an extension of its dependence on Russia. The removal of the Russian variable, in this context, intensified Azerbaijan’s urgent need to engage in “aggressive opportunism.”[2] Armenia’s deterrence strategy, to this end, is currently being constructed to mitigate the contours of this aggressive opportunism. Two concepts define this strategy: deterrence by denial and immediacy.

Diplomatization of Security

EVN Security Report: September 2022

Armenia’s security situation remains precarious, as Azerbaijan has exponentially increased its use of interstate conflict mechanisms, undertaking both large-scale invasions as well as incrementally utilizing hybrid warfare to justify violations of the ceasefire.

Read moreExamining the Context: EVN Security Report, September 2022 [Video]

Hybrid Warfare and the Asymmetrical Disparity

EVN Security Report: October 2022

The security context for the month of October can be better understood as the changing configuration between Armenia’s implementation of its diplomatization-of-security doctrine against Azerbaijan’s multi-tiered hybrid warfare doctrine.

Read moreExamining the Context: EVN Security Report, October 2022 [Video]

Armenia’s security policies, and the multilayered processes that inform and compose the overarching doctrines that shape the country’s defense architecture, remain one of the most vital, yet under-reported and under-studied areas of social, political and institutional importance. Limited public information on security policies and expert-driven inquiries into the development, implementation and implications of such policies, has contributed to a culture of confusion and uncertainty. More than ever, the Armenian nation needs informative, nuanced, and well-developed publications that unravel, inform and contribute to addressing Armenia’s security issues. To this end, EVN Report has launched a monthly security briefing, providing data-driven, in-depth analysis of the country’s monthly security situation by Dr. Nerses Kopalyan.

Deterrence by denial strategies are designed to deter actions by antagonistic states by ensuring or creating the perception that such actions are infeasible or will most likely fail. The objective is to develop sufficient capabilities that will diminish the aggressor state’s confidence in achieving its objectives and thus deter them from action. Under this strategic doctrine, the capability to deny amounts to the capability to defend.[3] This strategy is different from deterrence by punishment, which entails severe escalatory capabilities and large-scale punitive actions that will produce exceedingly high costs for the aggressor state. Considering the asymmetry in power parity between Armenia and Azerbaijan, and noting the collapse of extended deterrence, Armenia is neither in the position nor does it have the resources and capabilities to assume a deterrence by punishment doctrine. Further, the extant body of research on deterrence demonstrates that denial strategies are both more reliable and effective than punishment strategies.[4]

Immediate deterrence pertains to the formulation of a deterrence strategy that is more concrete, short term, and designed amidst urgency or crises, where the objective is to prevent a specific or imminent attack.[5] Extended deterrence, on the other hand, is an example of general deterrence, as the strategy revolves around an ongoing, persistent endeavor to stave off unwanted actions over a longer period of time. The ultimate objective is to have a robust general deterrence doctrine in order to reduce the necessity for immediate deterrence. However, noting the collapse of Armenia’s ersatz general deterrence doctrine under Russian-led extended deterrence, Armenia finds itself in an acute security crisis that stipulates the need for vigorous immediate deterrence. Commensurate with strategic immediacy is the broader conceptualization of deterrence. In its narrowest sense, deterrence refers solely to military tools of statecraft,[6] namely, using the “threat of military response to prevent a state from taking action.”[7] In its broader conceptualization, the scope of deterrence is extended to nonmilitary actions, especially development of hybrid warfare capabilities and resilience. Collectively, the strategic goal is to dissuade by means of presenting a threat to the antagonistic state and denying the success of the adversary’s immediate objectives. The underlying intent is to affect the calculus of risk and cost by denying Azerbaijan potential success and immersing Baku into the larger process of dissuasion. The goal of dissuasion is to convince the antagonistic state that the cost-benefit calculus of aggression places the aggressor state at a high risk of loss. Dissuasion is designed to make aggression as unnecessary as it is costly.[8]

Conceptualizing Azerbaijan’s Aggressive Opportunism

In order to cogently develop and enhance Armenia’s deterrence by denial strategy, and vigorously implement it as immediacy, Azerbaijan’s interests, objectives, motives, and imperatives must be qualified. But this qualification must not be through the lens of the deterring actor, Armenia, but rather, through the lens of the antagonistic actor, Azerbaijan. In essence, the deterring actor must fully conceptualize and understand what the strategic rationale of the antagonistic state’s aggressive opportunism is.

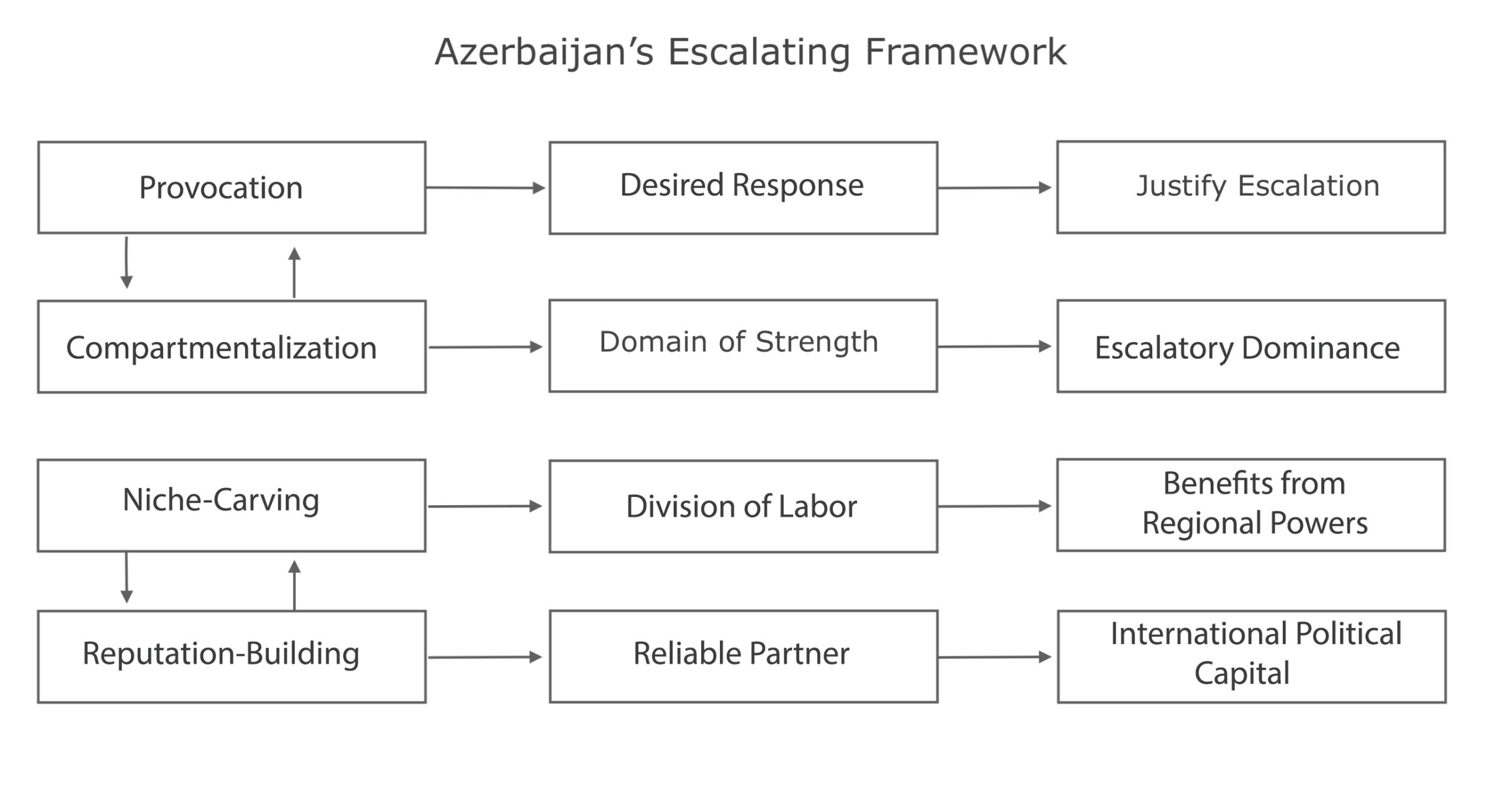

Azerbaijan’s escalatory behavior and its broader policy of aggressive opportunism may be understood through four main conceptual frameworks: provocation, compartmentalization, niche-carving and reputation-building.

Provocation

Azerbaijan engages in provocations through a multitude of mechanisms, from interstate militarized disputes, to hybrid warfare tactics, or threatening and irredentist rhetoric. The objective is to provoke a response from Armenia, or more specifically, to ascertain a desired over-reaction, which it can utilize to justify its own escalatory tactics and reinforce the bothsidesism that it has become accustomed to from the international community. This mechanism of provocations is also utilized through mirroring tactics, where Baku falsely accuses Armenia of initiating interstate militarized disputes and proliferating the misinformation to rationalize its own designs of provocation.

Compartmentalization

Azerbaijan engages in compartmentalization by isolating the conflict into a domain where it has escalation dominance, thus enhancing the overall power structure vis-a-vis Armenia. Prior to the 2020 Artsakh War, for example, not having been fully convinced that the Russian-led extended deterrence strategy was unsubstantial, it isolated the conflict into the domain of prolonged hybrid warfare and intense caviar diplomacy. After the 2020 Artsakh War, however, with the collapse of Armenia’s extended deterrence strategy, Baku isolated the conflict into the domain of incursions, intensification of hybrid warfare, and direct invasion into Armenia proper. At the same time, noting its relative failures in diplomacy, the collapse of caviar diplomacy, and growing Western support for Armenia, it diverted its resources away from this domain. In this context, Azerbaijan compartmentalizes its escalatory behavior based on its domain of strength.

Niche-Carving

Azerbaijan engages in niche-carving by enhancing its reciprocal capabilities vis-a-vis partners and strategic allies, thus establishing a division of labor in its regional responsibilities in relation to its more powerful partners. With Turkey, for example, Azerbaijan serves a specific and well-developed niche in the South Caucasus that both aligns with Turkey’s interests as well as serving these interests. By engaging in niche-carving, Azerbaijan adjusts its interests and activities to align it with its more powerful partners, thus reinforcing the mutual adjustment of interests. Similarly, Azerbaijan’s niche-carving in the energy sector has aligned Baku’s interests with that of Moscow, thus reinforcing its adjustment of interests vis-a-vis Moscow while also inducing the latter to accommodate Baku’s regional interests. By carving a niche, Azerbaijan offers its resources to larger partners, while at the same time utilizing the niche it carved to ascertain reciprocal outcomes.

Reputation-building

Azerbaijan engages in reputation-building by leveraging its military success against Armenia to posture itself as a regional actor, while at the same time leveraging its energy resources to posture itself as a reliable partner to Europe. Its dualistic reputation-building, while contradictory, do serve two important objectives. First, by establishing a reputation as a steadfast and belligerent state, Baku projects power both regionally and domestically. In the case of the latter, it allows for regime preservation, while in the case of the former, it enhances niche-carving. Azerbaijan’s continuous provocations towards Iran, for example, as low key as they are, are precisely designed to build Baku’s reputation as both an actor that can challenge a powerful neighbor (even if such a challenge substantively does not exist) and as a bulwark against Iran that the West should support. By cultivating this two-tiered reputation, Baku diverts attention from domestic problems, while at the same time using its regional reputation to advance its interests. Second, Baku has built a reputation as a reliable security partner, which has allowed it to bypass the intense criticism that other countries are subjected to for their crude human rights violations. Simultaneously, this reputation has also offered Baku international political capital when it comes to its escalatory behavior towards Armenia. Collectively, by developing a niche-specific reputation, Azerbaijan has been able to expansively engage in aggressive opportunism.

Overarchingly, Armenia’s deterrence by denial strategy must be crafted to counter and deconstruct each one of these conceptual frameworks that guide and account for Baku’s escalatory behavior. While Armenia has displayed some level of success in countering Azerbaijan’s provocation technique, it has struggled to address Baku’s ability at compartmentalization, while offering very little in the form of niche-carving and reputation-building. At the same time, Armenia has made inroads in reputation-building, specifically in democracy imaging and multilateralism. This, in turn, has allowed Yerevan to engage in some degree of niche-carving. These minor developments, however, remain limited and insufficient in countering Azerbaijan’s multi-tiered strategy. Thus, while the diplomatization of security has succeeded in curbing some of Baku’s escalatory endeavors, it remains but one portion of the need for a more comprehensive deterrence by denial doctrine.

Footnotes: