Listen to the article.

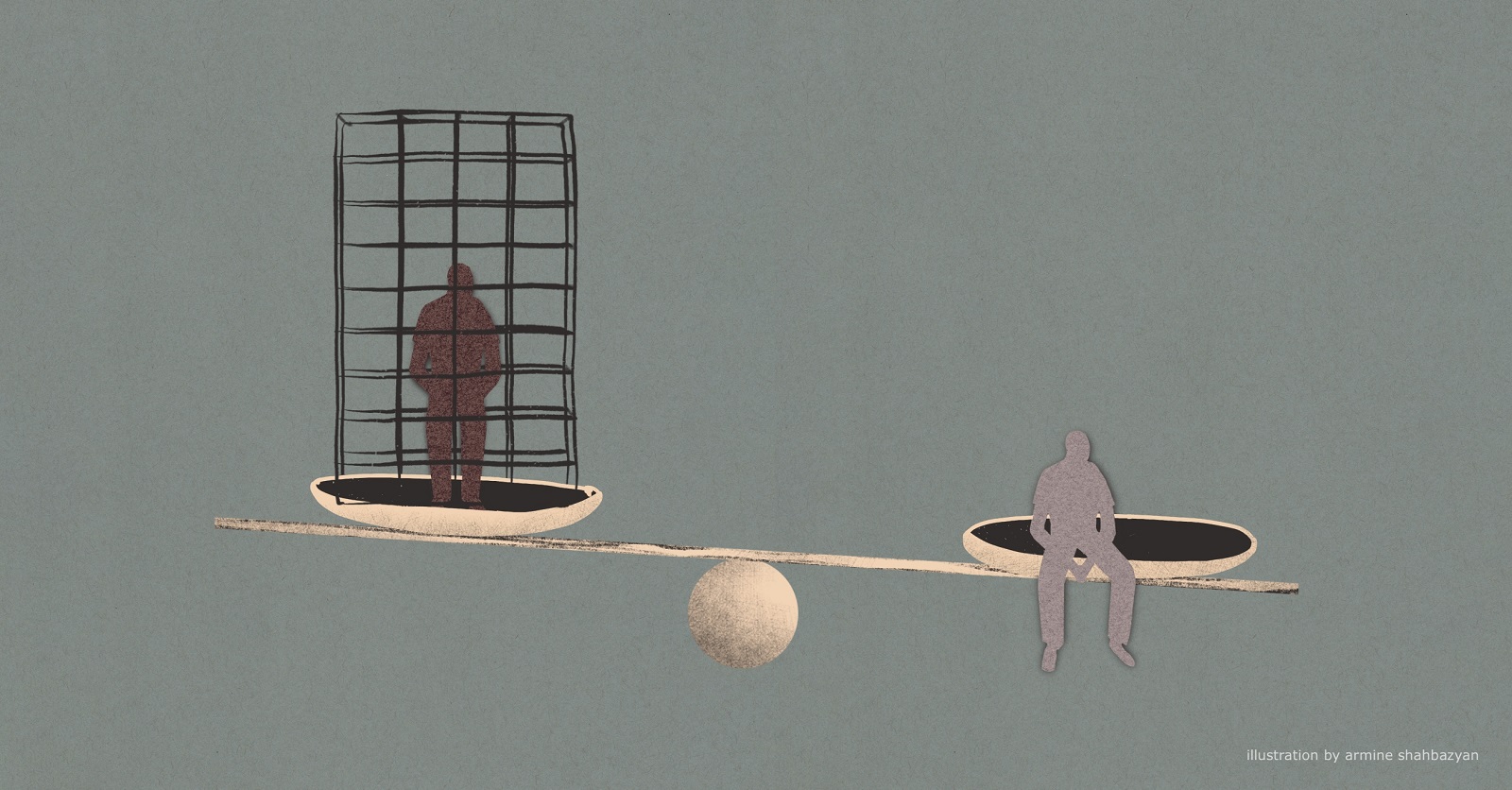

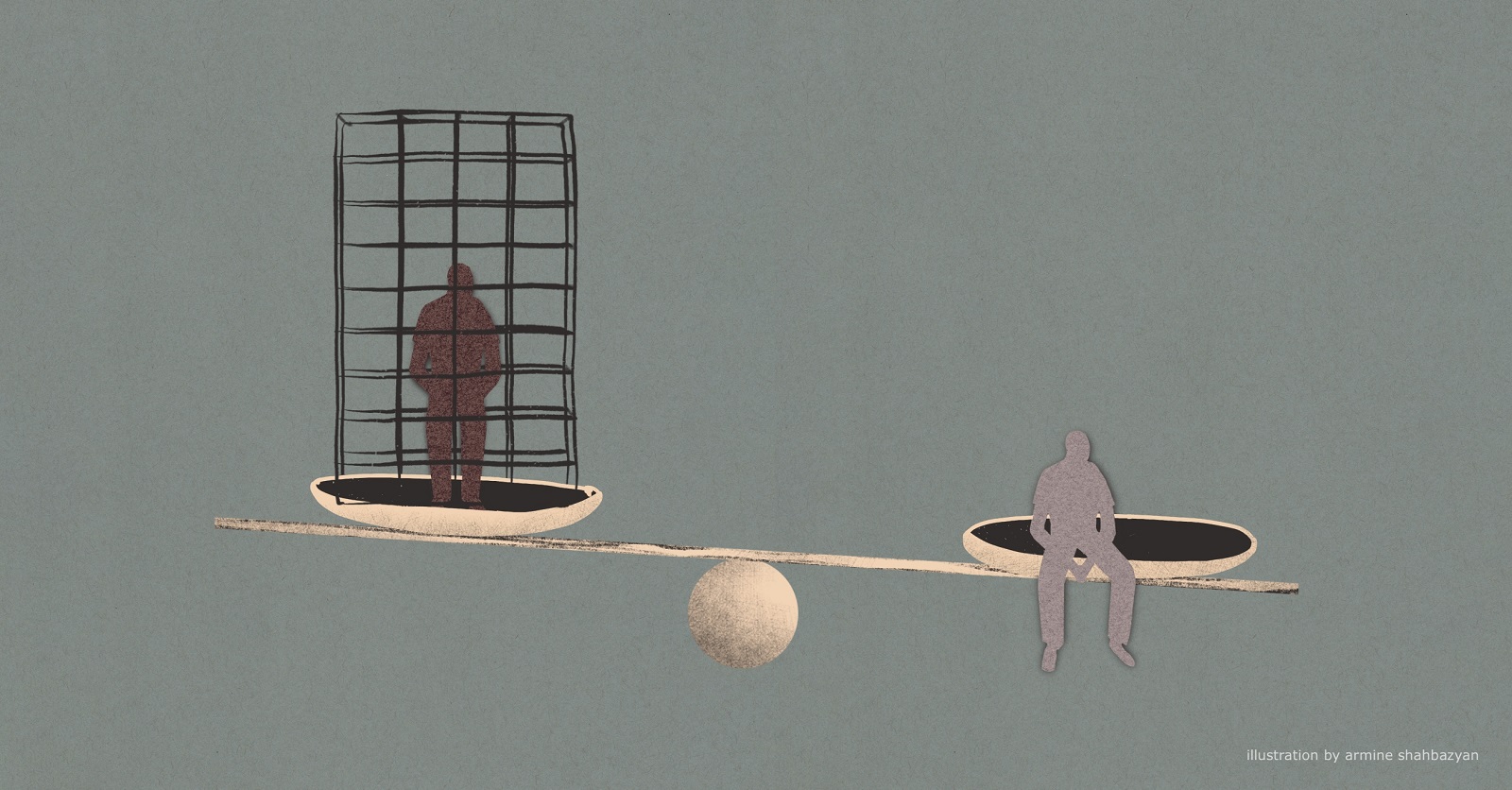

The state responds to individuals who have committed a crime through punishment. In cases where individuals have perpetrated serious offenses and present a threat to the public, incarceration is the prevailing recourse, effectively removing them from society. However, in instances where a crime is unintentional or a result of negligence, the justification for imprisonment is debatable. This is where probation services step in, providing an alternative to incarceration by allowing the individual a probationary period in freedom. Instead of punitive measures, the state applies the principle of restorative justice, giving the individual an opportunity to comprehend the ramifications of their actions, express remorse, and mitigate the likelihood of recidivism.

In Armenia, the Law on Probation enacted in 2016 and the Law on Probation Service that came into effect January 1, 2024, have established the practice of rehabilitating individuals rather than punishing them. This represents a shift from punitive measures to restorative justice.

This implies that the Probation Service will operate as an independent public service under the Ministry of Justice, with its own infrastructure including a personnel department and a separate budget. The law aims to make the service more appealing by increasing salaries, increasing benefits, and offering additional social guarantees. The probation service is expected to have another 100 positions.

Probation and Its First Application

Probation is an alternative to imprisonment, particularly for minor offenses. It allows individuals, as per the court’s decision, to serve their sentence or restraining order in a state of limited freedom, under certain controlled conditions, without being removed from society and their families. Probation aims to prevent reoffending by mitigating the influence of a criminal subculture. It also facilitates reconciliation between the offender and the victim.

Probation derives from the Latin “probare” — to prove, to test — and was coined by John Augustus, a bootmaker and penal reformer from Boston. In 1841, Augustus, a member of the Washington Abstinence Society who believed that alcoholics could be rehabilitated through kindness and understanding, requested the court to place an alcoholic convict under his supervision. The court agreed, providing the convict the opportunity to avoid short-term imprisonment for drunkenness. Three weeks later, the convict, escorted by Augustus, reappeared in court. Remarkably, not only his behavior, but also his appearance had transformed.

In the subsequent 18 years, Augustus undertook the responsibility of rehabilitating and reintegrating 1,946 convicts into society. Reportedly, only 10 cases were unsuccessful, with the remaining convicts undergoing positive change.

Inspired by John Augustus, other judicial systems, including the legal justice system in the United States, began using “probation” as an alternative to imprisonment.

Before the State Probation Service was established in 2016, Armenian courts had implemented non-custodial punishments. Their supervision was carried out by the Penitentiary Service’s subdivision on alternatives to incarceration.

In 2012, the strategic plan for legal and judicial reforms (2012-2016), proposed the establishment of the Probation Service. This service was intended to be an independent body within the Ministry of Justice, separate from the Penitentiary Service.

The Law on Probation was adopted in 2016, but the service started operating more efficiently in 2018, when its internal statute was also adopted.

The Service Providers

One benefit of introducing the probation service is to help alleviate strain on penal institutions. This service aims to prevent further criminal behavior by the accused and ensure compliance with court-ordered obligations. Moreover, it focuses on the rehabilitation of convicted individuals, safeguarding the physical and mental well-being of minors, and protects them from negative influences. Additionally, it aims to prevent repeat offenses and aid in the reconciliation between the probationer and the victim (or the victim’s successor).

Karen Hakobyan, who coordinates individual cases in the Probation Service of the Ministry of Justice, reported that as of February 2024, the Probation Service has 8,500 probationers and 108 employees implementing the service.

“In most cases, one officer handles 100 cases,” Hakobyan noted. “International experience shows that effective work can be conducted when an average of 50-60 cases are assigned per case officer.”

The probation officer’s salary ranges from 80,000 to 120,000 drams, which doesn’t adequately compensate for the numerous duties involved. These include attending 10-20 court hearings monthly, visiting various penitentiary institutions for each case, conducting home visits to probationers and victims or their representatives, and participating in meetings at the convict’s workplace or school, with family members, relatives, friends, neighbors. Despite the heavy workload, all these responsibilities are currently carried out at the officer’s expense. However, Hakobyan mentions that a salary increase is anticipated under the new law on the service.

“The draft law on officials’ remuneration was submitted to the National Assembly,” explains Hakobyan. “It includes a separate scale for the probation service and a proposed salary increase of 20 percent.”

According to Nare Hovhannisyan, President of the Center for Legal Initiatives NGO, the Law on Probation will create the preconditions necessary to attract professional staff to the service. However, she fears that the service may be filled with employees who prioritize punitive justice over restorative justice.

“There is a risk that law enforcement agents will approach the system with a punitive mindset rather than a rehabilitative one. This contradicts the philosophy of probation,” says Hovhannisyan, adding, however, that the Probation Service has limited influence because the individuals under probation are free.

The Beneficiaries

The Criminal Code specifies the crimes that result in the offender coming under the Probation Service’s jurisdiction without being imprisoned. In essence, a person who commits a crime without intent or negligence is not criminally liable in cases where the law mandates criminal liability only for intentional acts.

“Yes, there are well-established individuals who have a family, a job, and education, who have accidentally committed a crime,” said Karen Hakobyan. “We realize that there is not much to be done with this person, yet actions are taken as a result of addressing the risks and needs identified by our electronic program, which consists of eight sections. Based on this program, we can determine whether the risk of recidivism is high, medium, or absent. It also helps us decide whether the person needs to participate in resocialization measures.”

If rehabilitation is not necessary, the person continues to work and live a normal life with their family. However, if the probationer has not finished school, has been isolated from society, rehabilitation efforts are undertaken with them.

“We had minor probationers who, in fact, did not attend school. Our resocialization and rehabilitation department’s employees made great efforts to reintegrate them into schools,” says Hakobyan. He notes that today, the Probation Service has three minor probationers, all under house arrest, with one of who is receiving a school education.

Hakobyan further clarifies that house arrest involves various court-imposed restrictions: no telecommunication or internet use, no computer-based communication with others, no hosting of other people, and no phone conversations.

“In such restrictive conditions, it is not possible to exercise the right to education. Therefore, if the court allows an exception and these children can remotely receive a school education,” he adds.

Hakobyan says that the Probation Service has an average of 10-15 underage probationers and 100-150 female probationers per year.

Individuals on probation have a set of responsibilities and rights outlined by law. These entail maintaining lawful conduct, following punishment orders and other mandated measures, adhering to the directives of the probation officer, and the right to challenge any actions or inactions of the probation service, either through a higher authority or in court. Foreign individuals under probation are entitled to the assistance of an interpreter, provided by the state, to ensure their rights are exercised effectively.

The state should be attentive to each citizen. In the context of the statement, “Pushishment should not be forgiven”, if there is a legal avenue available, the preference should lean towards forgiveness.

Recently Published

Toxic Waste Beneath the City: Out of Sight, Out of Mind

Hazardous chemical substances in Armenia have been improperly managed and unsafely stored for decades. Former factories, now abandoned, still hold significant quantities of these hazardous substances. Mariam Tashchyan looks at the challenges of safely managing toxic waste and examines the government's responsibilities.

Read moreThe Four Villages: What We Know

Azerbaijan has been demanding Armenia withdraw from four villages in the Tavush region. There is much confusion around what these villages are and what a potential withdrawal could mean for Armenia. Hovhannes Nazaretyan explains.

Read moreWe Know What War Means, Don’t Scare Us With That Word

Residents of the border village of Voskepar express concerns about the expected launch of the demarcation and delimitation of the Armenia-Azerbaijan border. Lilit Avagyan met with villagers to hear their perspectives firsthand.

Read moreBeyond the Drone Hype: Unpacking Nagorno-Karabakh’s Real Lessons

The 2020 Artsakh War served as a stark reminder of the transformative role that drones are playing on the modern battlefield. Davit Khachatryan argues, however, that the overemphasis surrounding drones requires a more sober and critical analysis.

Read more