Listen to the article.

The issue of Soviet-era enclaves and “non-enclave” villages came to the forefront of Armenia-Azerbaijan talks earlier this year. Azerbaijan has recently demanded Armenia withdraw from the four “non-enclave” villages in the Tavush region. There is much confusion around what these villages are and what a potential withdrawal could mean for Armenia.

How It all Started

On October 7, 2023, just as Azerbaijan had captured all of Nagorno-Karabakh (Artsakh) and forcibly displaced the entire Armenian population, Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev told EU’s Charles Michel in a phone call that “eight villages of Azerbaijan were still under Armenian occupation, and stressed the importance of liberating these villages.” In a January 2024 interview, he made a distinction between “enclave and non-enclave villages.” He said the latter four “should be returned to Azerbaijan without any preconditions,” while the latter four (located within three enclaves) should be discussed by a “separate expert group.”

On March 9, 2024, the Azerbaijani government, in the name of Deputy Prime Minister Shahin Mustafayev’s office, issued a statement demanding the “immediate liberation” of the “four non-exclave Azerbaijani villages occupied by Armenia.” This came just two days after the March 7 meeting of the Armenian-Azerbaijani commission on delimitation, chaired by Mustafayev and his Armenian counterpart Mher Grigoryan.

The Four Villages

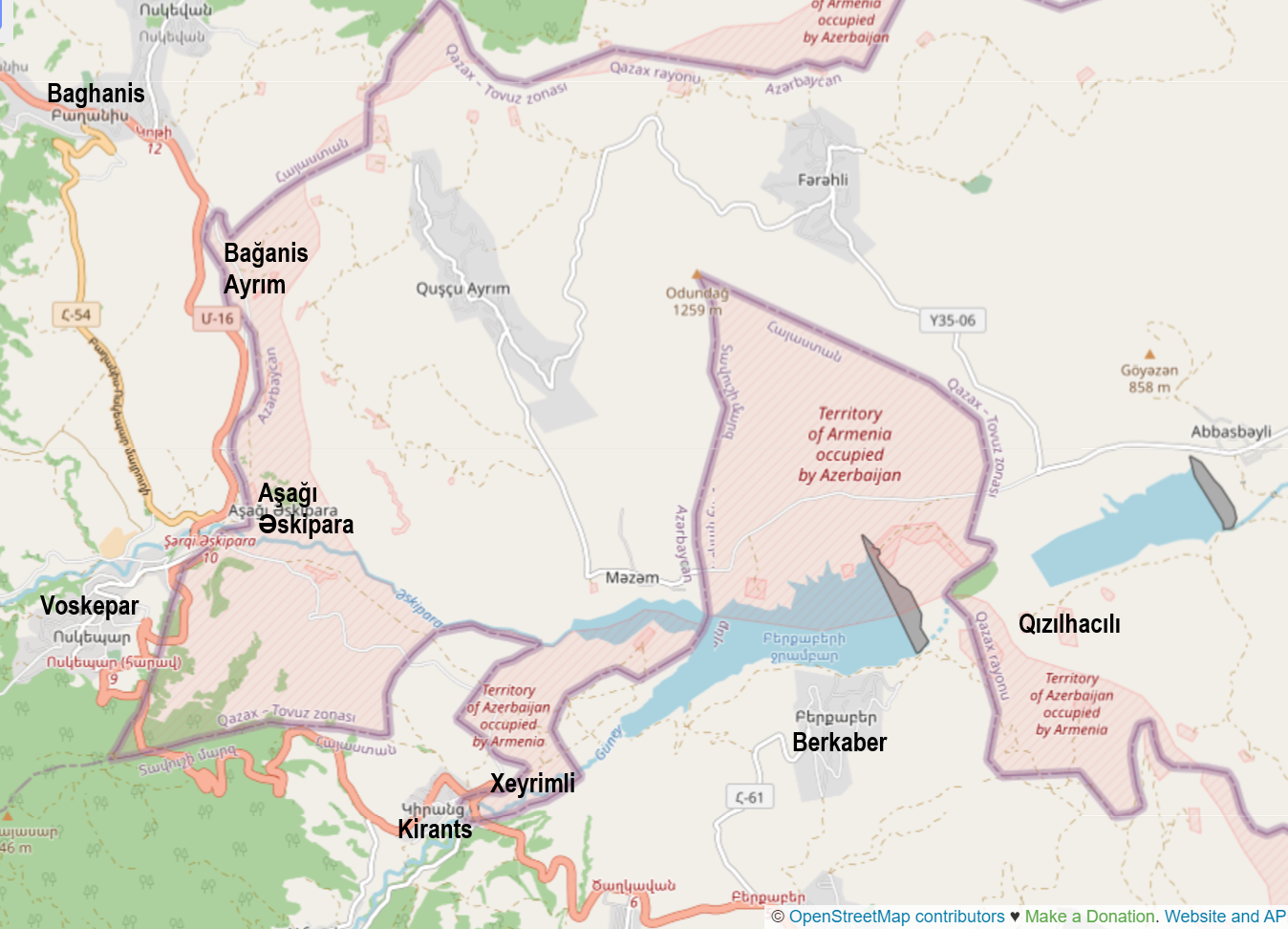

The four “non-enclave” villages in question are Baghanis Ayrim, Ashaghi (Lower) Askipara, Kheyrimli, and Gizilhajili. They were part of (Soviet) Azerbaijan and were captured by Armenian forces in the early 1990s. (According to the Azerbaijani government, Baghanis Ayrim fell to Armenian forces in March 1990, while the other three were captured between March and June 1992). As the Azerbaijani residents fled amid the ongoing war, these villages have long been uninhabited and their buildings stand in ruins.

One of these villages, Gizilhajili, appears to be more of a buffer zone and partly under Azerbaijani control rather than that of Armenia. Armenians have dug trenches just outside the village, while Azerbaijani fortifications are situated in the middle of its ruined houses. Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan insisted in a recent speech to his party members that it is entirely controlled by Azerbaijan.

These villages were captured with the aim of ensuring the safety of a major route and nearby Armenian settlements. They are strategically placed on the Yerevan-Ijevan-Tbilisi highway that runs through the Armenian village of Voskepar and crosses into de jure Azerbaijani territory.

A map of the area shown during Public TV’s interview with parliament speaker Alen Simonyan. Armenian villages are shown in green, the four Azerbaijani villages in question are shown in red and the de jure border in yellow.

De Jure (Soviet) Borders

In October 2022, as part of ongoing peace talks, Armenian and Azerbaijani leaders agreed to recognize each other’s territorial integrity through the 1991 Alma Ata Declaration. In practice, it means recognition of Soviet-era administrative borders (between then-Soviet republics) and commitment to carry out delimitation based on it. Pashinyan and Aliyev confirmed their commitment to that declaration and the territorial integrity of Armenia (29,800 km²) and Azerbaijan (86,600 km²) when they met in Brussels in May 2023.

The process is complicated by Azerbaijan’s refusal to agree on a specific map for delimitation and demarcation of the border. When EU, French, and German leaders met with Pashinyan in October 2023, they endorsed the idea of using “the most recent USSR General Staff maps that have been provided to the sides.” Pashinyan said the following month that Armenia and Azerbaijan have a “certain understanding” that Soviet General Staff maps from 1974 to 1990 should be used. But in his January interview, Aliyev questioned the use of maps from the 1970s on. Besides his often-repeated irredentist claims to much of Armenian territory, Aliyev claimed that parts of Azerbaijani territory were “gifted” to Armenia as late as May 1969. Only during the reign of his father Heydar Aliyev as leader of Soviet Azerbaijan were “land gifts” to Armenia “stopped”. Consequently, he argued, Azerbaijan “strongly objected” to the use of 1970s maps and “can never agree” to it.

Despite not explicitly recognizing Armenia’s territorial integrity, Azerbaijan insists, having the upper hand, that delimitation should start with Armenia’s withdrawal from these four villages.

Pashinyan Calls for Unilateral Withdrawal

During his March 12 press conference, Pashinyan stated that the four villages are not part of Armenia and were not part of Soviet Armenia prior to 1991. “The names of the villages being raised in the Azerbaijani press have never existed in the territory of the Republic of Armenia; moreover, not only during Soviet times but even afterward,” he said. On March 18, nearly ten days after the Azerbaijani demand, he visited Voskepar and Kirants, the Armenian villages closest to the four villages in question, to meet with locals and address their concerns. His message, in short, was that those four villages are not part of Armenia’s sovereign territory and must be ceded to Azerbaijan. Otherwise, Pashinyan warned, Azerbaijan would attack Armenia as early as by the “the end of the week.”

Pashinyan tacitly admitted that the move would be unilateral, noting that Azerbaijan would not reciprocate Armenia’s move by withdrawing from territories of Armenia it currently occupies, which amounts to around 208 km², according to the MFA. Most of it was captured in a series of incursions into Armenia between May 2021 and September 2022. Armenian officials have repeatedly voiced that Azerbaijan controls the “vital territories”, including agricultural land and strategic heights, of 31 Armenian municipalities. For instance, in the vicinity of Jermuk, a resort town, Azerbaijani forces advanced as much as 7.5 km into Armenian territory in September 2022, while in Berkaber, a village in Tavush, Azerbaijan has occupied around 800 hectares of arable land since the early 1990s.

A week after Pashinyan’s visit to the area, Caliber, a notorious Azerbaijani government-linked outlet, threatened Armenia with an invasion if the four villages were not returned “as soon as possible.” It prompted a response by Toivo Klaar, the EU’s envoy to the region, who said that “threats against Armenia in Azerbaijani media channels are unacceptable” and that “genuine negotiations on border delimitation are needed.” In a speech to party members on March 30, Pashinyan reiterated that Azerbaijan is “trying to find excuses to start a new, large-scale war in the region.”

The Current Situation and Potential Threats

The withdrawal of Armenian forces to the de jure (Soviet-era) border would bring the de facto line of contact much closer to the Armenian villages of Voskepar and Kirants. Most recent official estimates put their population at 721 and 328, respectively. Next to be affected would be Berkaber and Baghanis with their 374 and 840 residents. These and other villages would find themselves very close to Azerbaijani troops or guards when they are deployed to the de jure border.

In the case of Voskepar and Kirants, there is the immediate threat of becoming partially isolated as the roads leading to the villages appear to criss-cross the de jure border and thus, would come under effective Azerbaijani control in the event of an Armenian withdrawal. This would happen if the withdrawal occurs before the construction of new or alternative roads. The prospective withdrawal may also directly affect another village, Acharkut (population 171), as the road from the regional center of Ijevan leading to that village appears to pass very close to the de jure border making it potentially unsafe.

A map of the area on OpenStreetMap shows de jure Armenian territory under Azerbaijani control and de jure Azerbaijani territory under Armenian control shaded in red.

Most concerning is the potential disruption of the Ijevan-Noyemberyan highway, which would, in the absence of an alternative, significantly impair local connectivity in northeastern Armenia. The highway also forms a section of a major route connecting Yerevan and Tbilisi. It runs through Voskepar and in some portions crosses through de jure Azerbaijani territory, a detail confirmed by both Pashinyan and parliament speaker Alen Simonyan.

Notably, in its travel advisory, the U.S. State Department states, without specifying this area in particular, that travelers should exercise caution on “roads near Armenia’s border with Azerbaijan” as they “may cross international boundaries without notice.” Consequently, Google Maps recommends the Yerevan-Vanadzor-Alaverdi route as the primary road to Tbilisi, and does not even suggest the Yerevan-Ijevan-Noyemberyan route as an option. But the latter route is currently more commonly taken when driving between Yerevan and Tbilisi. The Yerevan-Vanadzor-Alaverdi-Tbilisi highway is actually slightly shorter (276 km) than the potentially threatened Yerevan-Ijevan-Noyemberyan-Tbilisi highway (285 km), but the former is often avoided has it has been undergoing extensive repairs for years.

There are further concerns that another key piece of infrastructure, the pipeline that brings gas to Armenia from Russia, may be threatened in the event of a withdrawal. According to the map available on the website of Gazprom Armenia, the sole operator of Armenia’s natural gas distribution network, the main gas pipeline does run through this general area, but its exact route remains unclear. Parliament speaker Simonyan said in a recent interview that the pipeline does not pass through de jure Azerbaijani territory.

To address these potential threats, Tatul Hakobyan, a researcher and analyst, has called on the Armenian government to relocate the Ijevan-Noyemberyan highway and the gas pipeline deeper into Armenian territory and build a (new) bridge in the Kirants-Acharkut area. Pashinyan said in his March 12 interview that Armenia must take measures “shortly” to ensure that all types of infrastructure pass through de jure territory of Armenia and that he had already issued directives for that purpose.

Although not a piece of infrastructure, there are also concerns surrounding the seventh century church of Voskepar. Parliament speaker Simonyan affirmed that it is on de jure Armenian territory. This is further corroborated by a 1976 Soviet military map available online, where the church, shown as a small cross, is on the Armenian side, immediately west of the border between Soviet Armenia and Soviet Azerbaijan.

Russian Presence

For the past three years, Russia has maintained a presence in the area. In August 2021, a Russian flag was seen flying over a small building, apparently a guard post, in Voskepar. Armenia’s Defense Ministry confirmed in a statement that Russian border guards had been deployed as part of cooperation between the two countries and that construction works were carried out for ensuring their “rear facilities”. Hayk Ghalumyan, governor of Tavush, told Hetq at the time that the Russian guards were monitoring the situation, and officials refused to further elaborate on why a Russian guard post was set up there. A year later, in August 2022, Tatul Hakobyan reported that a separate building was under construction that would house Russian border guards. This long rectangular facility, much larger than the original guard post, is situated further north, on the road between Voskepar and Baghanis. It first appeared on satellite imagery in mid-July 2022. It appears to be functional as of late March 2024.

Photo of the Russian military facility on the Voskepar-Baghanis road. November 2022.

It remains to be seen how the delimitation and demarcation of the border unfold, but as long as Azerbaijan maintains the upper hand and superior military capabilities, it will likely continue to make unilateral demands.

Also see

Enclaves Enter Armenia-Azerbaijan Peace Talks

The issue of tiny but strategically placed Soviet-era enclaves in Armenia and Azerbaijan has come to the forefront of peace talks in recent months. Hovhannes Nazaretyan maps it out.

Read moreWe Know What War Means, Don’t Scare Us With That Word

Residents of the border village of Voskepar express concerns about the expected launch of the demarcation and delimitation of the Armenia-Azerbaijan border. Lilit Avagyan met with villagers to hear their perspectives firsthand.

Read morePolitics

Amid Security Concerns, New Poll Indicates Positive Direction With Continued Russian Retreat

The latest survey by the International Republican Institute, conducted in December 2023, reveals the consolidation of public distrust in Russia, strong support for the Government’s pivot toward the West, and a growing sophistication in the Armenian public’s understanding of its complex security concerns.

Read moreHow Azerbaijan Deceives and Harasses the International Community

Azerbaijan has been using military and diplomatic coercion to achieve its maximalist and expansionist objectives, employing wide-ranging tools of hybrid war while also deceiving and harassing international actors. Sossi Tatikyan explains.

Read moreEU, U.S. Elections Could Test Armenia’s Resilience

As the geopolitical landscape in the South Caucasus remains precarious, potential changes in EU and U.S. leadership can pose additional challenges for Armenia. Amid these uncertainties, Armenia's diplomatic efforts become increasingly important and serve as a test of its resilience.

Read moreOpinion

Beyond the Drone Hype: Unpacking Nagorno-Karabakh’s Real Lessons

The 2020 Artsakh War served as a stark reminder of the transformative role that drones are playing on the modern battlefield. Davit Khachatryan argues, however, that the overemphasis surrounding drones requires a more sober and critical analysis.

Read moreTowards a Franco-Armenian Strategic Partnership?

The Coordinating Council of Armenian Associations in France recently hosted its annual dinner in Paris against the backdrop of heightened geopolitical tensions and concerns over Armenia's security. The focus shifted to the role of France in implementing deterrence measures and sanctions against Azerbaijan.

Read moreBetween State and Fatherland: A Tale of Two Mountains

Mount Ararat doesn't stand as an obstacle to building a functional state, and suddenly loving Mount Aragats will not help us achieve our goals. Before we jettison our national symbols en masse, we need concrete plans and state-driven programs to improve the lives of an already beleaguered nation, writes Daniel Tahmazyan.

Read more