Listen to the article

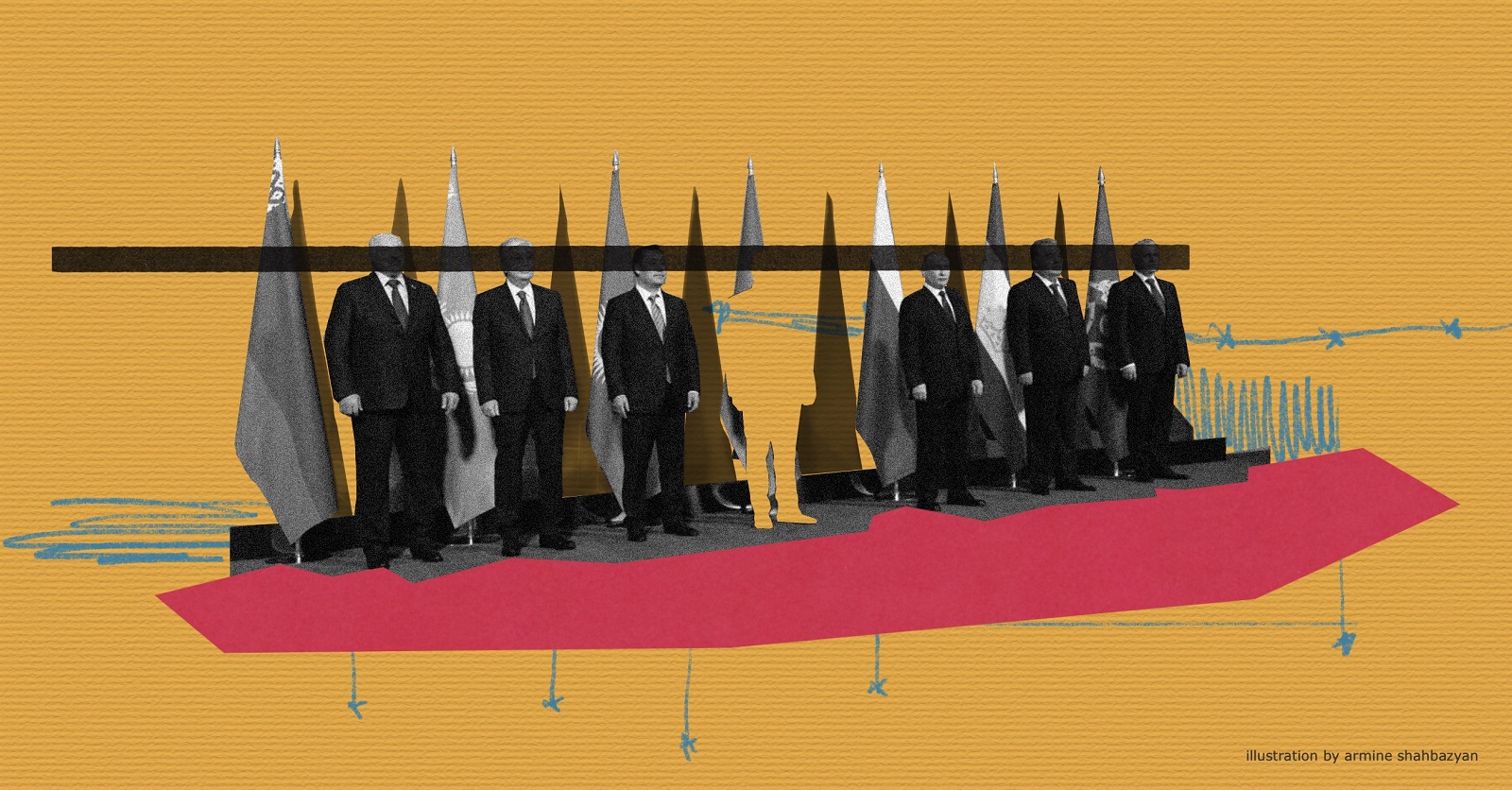

Armenia, once a staunch ally of Russia, has begun to distance itself from Moscow. As a member of all Russian-led organizations, including the Commonwealth of Independent States, the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU), and the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), Armenia’s allegiance seemed unwavering. However, the relationship started to fray after the CSTO failed to respond when Azerbaijan attacked Armenia’s eastern borders in September 2022.

This inaction highlighted the perceived ineffectiveness of the CSTO in protecting its members, reinforcing the notion that the organization serves more as a political tool for Russia to exert influence over its allies rather than a reliable security guarantor.

In February 2024, Armenia’s Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan said that Armenia had “essentially frozen” its membership in the organization. Three months later, in May, Yerevan also announced that it will not contribute to the budget of the security bloc.

The Organization

The CSTO is a Russia-led military alliance of six former Soviet states. The mandate of the CSTO is to ensure the collective defense of any member facing external aggression. Political scientists have described it as the Eurasian counterpart of NATO.

In May 1992, the heads of Armenia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan signed the Collective Security Treaty, laying the foundations for the Collective Security Treaty Organization. A year later, three other former Soviet states, Azerbaijan, Belarus and Georgia also joined. The treaty entered into force in April 1994 for five years, with the possibility of extension. In 1999, Russia, Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan decided to renew the treaty, while Georgia, Azerbaijan and Uzbekistan chose not to. In 2002, those six agreed to create the Collective Security Treaty Organization as a military alliance. Uzbekistan returned to the alliance in 2006 but withdrew its membership in 2012.

The most crucial clause of the CSTO charter is Article 4, which stipulates: “If one of the State Parties is subjected to aggression by any state or group of states, then this will be considered as aggression against all State Parties to this Treaty.” It goes on to say that in the event of an act of aggression against any of the participating States, all other participating States will provide the necessary assistance, including military, and will also provide support at their disposal in exercising the right to collective defense.

Article 3 of the Charter states that the objectives of the Organization are the strengthening of peace, international and regional security and stability, the collective protection of the independence, territorial integrity, and sovereignty of the member States.

The organization supports arms sales and manufacturing as well as military training and exercises. It uses a rotating presidency system in which the state leading the CSTO changes every year.

The CSTO charter stipulates two regional groups (Russia-Belarus and Russia-Armenia) that can react to external military aggression; a 4,000-member Collective Rapid Deployment Force for Central Asia; and a 20,000-member Collective Rapid Reaction Force, both of which are designed to respond quickly to the challenges and threats to the security of CSTO member states. There is also a collective peacekeeping force, including around 3,500 soldiers and officers and more than 800 civilian police officers.

It is evident that the CSTO was conceived by Russia as a multilateral institution to project its power regionally. In particular, the organization has given Russia the power to block NATO operations in the region

CSTO Inaction in Action

On May 12, 2021, Azerbaijani forces crossed into Armenia’s Syunik region near Black Lake (Sev Lich), advancing 3.5 kilometers into Armenian territory. The next day, Armenia’s Defense Ministry reported further Azerbaijani advances in the Vardenis (Gegharkunik region) and Sisian (Syunik region) areas under the pretext of “clarifying” state borders. Tensions escalated as Azerbaijani troops remained on Armenian soil, with Armenian authorities reporting that approximately 1,000 Azerbaijani soldiers occupied Armenian territory.

Armenia’s Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan said during an extraordinary session of the Security Council that the situation on Armenia’s borders fully corresponded to paragraph 2 of article 2 of the Collective Security Treaty, which stipulates that “in the event of a threat to the security, stability, territorial integrity, and sovereignty of one or more member states, the member states shall immediately activate the mechanism of joint consultations to coordinate their positions, develop and adopt measures to assist such member states in order to eliminate the arising threat.”

On May 14, Yerevan officially appealed to the CSTO. A general consultation took place on May 19 in Dushanbe during the meeting of the CSTO Council of Foreign Ministers. The details of the discussion were not made public. About two months after Armenia’s appeal, on July 3, CSTO Secretary General Stanislav Zas announced that the escalation on the Armenian-Azerbaijani border was a “border incident” and that the CSTO’s “potential is used only in cases of aggression or [an attack on one of the member states].”

The CSTO did intervene when unrest erupted in Kazakhstan in January 2022. When the deadly fuel protests started in Kazakhstan, Armenia held the rotating presidency of the CSTO. As the situation escalated, President Kassim Jomart Tokayev of Kazakhstan turned to the CSTO to help maintain order. The organization, chaired by Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan, immediately initiated consultations and decided to deploy a peacekeeping force to Kazakhstan to protect objects of strategic importance. Armenia sent 100 peacekeepers to Kazakhstan.

At the time, Armenia’s Prime Minister announced that one of the key priorities of Armenia’s presidency was strengthening the organization’s crisis response mechanisms. “Based on this, we expect that the CSTO member states will make joint efforts to further improve these mechanisms, which will undoubtedly contribute to both the further development of cooperation between the member states and the strengthening of the relevant structures and mechanisms of the Organization.”

Armenia’s Security Council Secretary Armen Grigoryan explained why Armenia was proactive in ensuring that the CSTO stepped up to help Kazakhstan while it had failed to aid Armenia in May. According to Grigoryan, Armenia had two main interests. Firstly, Yerevan attached great importance to the responsibility it held during its turn in the rotating presidency. Secondly, Armenia was invested in seeing these mechanisms work.

Grigoryan pointed out that for the first time in its history, CSTO mechanisms actually functioned and expressed hope that, should Armenia need them in the future, those mechanisms will function again.

Nine months after the unrest in Kazakhstan, when Armenia was again attacked by Azerbaijan, CSTO mechanisms failed to work. At midnight on September 13, 2022, Azerbaijan launched a large-scale offensive against the eastern border of Armenia, targeting the regions of Gegharkunik, Vayots Dzor and Syunik––almost the entire eastern frontier of the country. In the heavy fighting that lasted for two days, over 200 Armenian servicemen and civilians were killed, dozens of buildings were destroyed, over 7,000 people had to be evacuated from their homes, and Azerbaijan occupied approximately 150 square kilometers of Armenia’s territory.

Armenia applied to the CSTO based on Article 4 of the charter. Late in the evening on September 13, on Armenia’s request, an online extraordinary session of the CSTO Collective Security Council took place, chaired by Armenia’s Prime Minister (Armenia still held the presidency of the organization). After Pashinyan presented the situation on the Armenian-Azerbaijani border, the council decided to send a mission to Armenia, headed by Secretary General Stanislav Zas, to set up a working group to assess the situation and prepare a detailed report for the heads of states on the Armenia-Azerbaijan border.

On September 14, the deputy foreign minister of Kazakhstan told reporters that it was “difficult to speak of any border violation” as the border between Azerbaijan and Armenia is not demarcated.

The CSTO mission, led by Chief of the Joint Staff Anatoly Sidorov arrived in Armenia on the evening of September 15. While in Armenia, Sidorov said that the CSTO was trying to be as objective as possible and it was too early to talk about conclusions.

The day after Sidorov’s arrival, Security Council Secretary Armen Grigoryan complained that there was no more hope the CSTO mechanisms would function to support Armenia in achieving the withdrawal of Azerbaijani forces from the sovereign territory of Armenia. He added that Armenia’s demand from the CSTO had been to provide military, political and security assistance to protect the sovereignty of the country, but it had not been fulfilled. “Naturally, we are not satisfied,” he said.

The CSTO delegations headed by Anatoly Sidorov and Stanislav Zas presented reports and suggested action plans to Armenian authorities, but no further steps were taken by the Organization.

Two months after the Azerbaijani attack against Armenia, on November 23, 2022, a session of the CSTO Collective Security Council took place in Yerevan. During the session, the member states of the organization prepared documents on the “Declaration of the Collective Security Council of the CSTO” and “The Joint Measures to Provide Assistance to the Republic of Armenia” which Nikol Pashinyan, as the chairman of the CSTO, refused to sign.

Pashinyan criticized the CSTO for its lack of response to Azerbaijan’s aggression, stressing that it raises significant questions about the organization’s effectiveness and its image among Armenians. He emphasized the need for a clear political assessment of the CSTO’s zone of responsibility in Armenia, arguing that without it, the organization’s credibility is at stake. While he acknowledged that restoring territorial integrity is important, he stressed that this does not imply a demand for military intervention, as Article 3 of the CSTO Charter prioritizes political measures for protecting member states’ territorial integrity. Thus, Armenia expected two things from the CSTO: to define its area of responsibility in Armenia and to give a political assessment of Azerbaijan’s aggression.

As Armenia voiced its discontent with the CSTO for not fulfilling its obligations, there were talks that Armenia might leave the security organization. Yerevan reaffirmed on many occasions that it did not plan to do so but expected a clear response to its concerns. Meanwhile, as Armenia started forging closer ties with the U.S. and the EU, it began to distance itself from the CSTO.

Most notably, while Yerevan declined a CSTO monitoring mission on its borders, it accepted a European monitoring mission (EUMA) that began in October 2022 and was extended into a two-year mission in January 2023. Armenian officials started refraining from participating in any CSTO meetings and military drills. Furthermore, in early 2023, Armenia refused to host CSTO military exercises. In March 2023, Armenia relinquished its quota of Deputy Secretary-General of the CSTO. In September 2023, Yerevan recalled its envoy from the CSTO and has not appointed a new one since.

Armenia’s Bilateral Relations With CSTO Member States

Armenia’s relations are not only strained with the CSTO itself, but bilateral relations have significantly worsened with main ally Russia and recently also with Belarus. On the other hand, there are continued talks with Kazakhstan on cooperation in different spheres, including defense and security. With Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, Armenia has very limited interactions. This article will present an overview of Armenia’s relations with each of the member states of the CSTO.

Russia

Among the CSTO member states, Armenia’s closest bilateral ties are with Russia. Russia used to be Armenia’s main military ally and remains its main economic partner. Since 2019, trade with Russia has more than tripled, growing from $2.2 billion in 2019 to almost $8 billion in 2023. Russia’s share in Armenia’s overall trade turnover is over 30%. Armenia receives most of its natural gas from Russia. The railroad system in Armenia is operated by South Caucasus Railway, owned by the Russian Railway, which is fully state-owned. Russia also operates and is the sole supplier of uranium for Armenia’s Nuclear Power Plant, which generates around 40% of Armenia’s electricity.

While Armenia’s economy is still highly dependent on Russia, the aftermath of the 44-day war revealed cracks in Armenia’s Russia-led security architecture. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and Azerbaijan’s attack on Armenia in September of that year led to the collapse of that security structure. Before the 2020 war and subsequent Azerbaijani attacks against Armenia, CSTO member and Armenia’s ally Russia had supplied non-CSTO member Azerbaijan with 85% of its offensive weaponry. This was evident as early as April 2016, when Azerbaijan attacked Artsakh, and there were low-intensity skirmishes on the Armenia-Azerbaijan border near Tavush.

The Russian-Armenian defense partnership is not only part of the CSTO but is regulated by three agreements. The 1997 Treaty on Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance states that the two countries will defend each other if either feels threatened by an armed attack. The treaty obliges both parties to take all necessary measures to eliminate threats to peace, breaches of peace, or acts of aggression against them by any state or group of states, and to provide each other with necessary assistance, including military aid.

The 1995 Treaty between the two countries on the Russian military base on the territory of the Republic of Armenia regulates the presence of Russia’s 102nd military base in the town of Gyumri. According to the treaty, the military base, in addition to protecting the interests of the Russian Federation, jointly with Armenia’s Armed Forces, ensures the security of the Republic of Armenia along the external border of the former USSR (Armenia’s borders with Iran and Turkey).

And, the 1992 Treaty on the status of the Border Troops of the Russian Federation stationed in Armenia puts the Russian FSB in charge of guarding Armenia’s border with Turkey and Iran. After the 2020 Artsakh War, Russian border guards were also deployed in Syunik and Gegharkunik along the new border with Azerbaijan. Before the 44-day war, Syunik bordered Nagorno-Karabakh from the east, and the Azerbaijani exclave of Nakhijevan from the west.

The Russian FSB was also present in the Zvartnots International Airport in Yerevan. In an unprecedented move, early this year, Armenian authorities announced that they had asked the Russian guards to withdraw from the airport as their services are no longer required. Later, it was announced that Yerevan and Moscow agreed that Russian border guards would also leave Syunik and Gegharkunik. Russian border guards left these positions on August 1.

While Armenia has made progress in diversifying its defense partnerships, expanding its economy presents a greater challenge. Although Armenia has the potential to enhance its economic relations with the European Union, particularly in trade, the European market is highly regulated. To succeed, Armenia will need to undertake significant reforms and improve the quality of its products to meet European standards and effectively compete in European markets.

Belarus

Armenia’s engagement with Belarus predominantly occurs through post-Soviet, Russia-led organizations such as the CSTO, the EEU, and the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). Economic cooperation between the two former Soviet states is moderate: Belarus exports machinery, chemical products, and foodstuffs to Armenia, while Armenia mainly exports agricultural products and alcoholic beverages to Belarus.

There is no substantial defense cooperation between Armenia and Belarus, however, Minsk has long been an arms supplier to Baku. Belarus’ defense cooperation with Azerbaijan and its strong support for Baku, both before and after the 2020 Artsakh War, has always caused friction with Armenia. The tension between the two countries peaked in June when Pashinyan announced in parliament that neither he nor any other Armenian official would visit Belarus because of Minsk’s support for Azerbaijan.

In May, Pashinyan had announced that he knew of at least two CSTO members who had worked against Armenia in the preparation of the war.

In May, Lukashenko visited Shushi with Azerbaijan’s President Ilham Aliyev. During the trip he recalled his conversation with Aliyev in which the two leaders had discussed Azerbaijan’s possible victory in the war: “I remember our conversation before the war [2020 Artsakh war]], before your liberation war, when we were having a philosophical discussion around the dinner table. We concluded then that it was possible to win the war.”

Subsequently, Yerevan and Minsk recalled their ambassadors for consultations. At the time, leaked documents revealed that Belarus supplied advanced weaponry to Azerbaijan between 2018 and 2022, which were used during the 2020 Artsakh War.

As of 2023, the trade volume between Armenia and Belarus has totaled to $188 million, placing Belarus 17th on Armenia foreign trade list. Despite tense political relations, the trade partnership between the two countries continues to grow moderately. Amid the tension, official Belarus has announced that it does not intend to worsen relations with Armenia as the countries have mutually beneficial trade relations.

Kazakhstan

After Russia, Kazakhstan is the second most significant country in the CSTO. It has the second-largest economy and the second-largest defense budget. While Armenia’s relations with Russia and Belarus have significantly worsened, there seems to be some progress with Kazakhstan.

In April, Kazakhstan’s President Kasim-Jomart Tokayev visited Armenia, where he met several officials, including Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan. During the visit, the leaders of Armenia and Kazakhstan signed a joint statement expressing confidence in strengthening interstate relations and mutually beneficial cooperation, aligning with the fundamental interests of their peoples. They announced plans to enhance bilateral cooperation and engage constructively within international organizations, particularly the Eurasian Economic Union and the Commonwealth of Independent States. The leaders emphasized the importance of continued defense cooperation, development of transport and transit initiatives, and ensuring uninterrupted communication. The statement highlighted the need for mutually beneficial economic cooperation, aiming to boost trade, fuel and energy collaboration, and partnerships in various sectors like agriculture, mining, and technology.

Among Armenia’s CSTO counterparts Kazakhstan has the most balanced relations with Russia and the West (EU and U.S.). There are arguments that, like Armenia, Kazakhstan is also striving to develop an independent foreign policy following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. President Kassim Jomart Tokayev has announced that Kazakhstan will observe international sanctions imposed on Russia after the Ukraine invasion but will not risk bilateral trade with Moscow. It is alleged that Kazakhstan does bypass the sanctions; however, on the surface, it is trying to show that it is maintaining them.

Although Kazakhstan is regarded as a close partner of Azerbaijan, there is potential for Armenia to develop bilateral relations with its CSTO counterpart. Kazakhstan can also be a source of uranium for Armenia.

Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan

While much focus is placed on Armenia’s relations with Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan, there is relatively little happening in its interactions with the other CSTO members — Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. Trade volumes with these countries are minimal. Armenia’s trade with Kyrgyzstan amounted to $29 million in 2023, a significant rise from just over $6.5 million in 2022 and $3.3 million in 2019. However, trade with Tajikistan has declined, with 2023 figures at $1.5 million compared to $1.7 million in 2019, although there was an increase from $1.2 million in 2022. Additionally, there have been no bilateral visits by Armenian state officials to Kyrgyzstan or Tajikistan in the past five years.

It is also noteworthy that Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan are involved in their own border disputes.

A Controversial Membership

Armenia’s membership in the CSTO has long been controversial, as most member states have closer ties to Azerbaijan than to Armenia. Another distinguishing factor for Armenia compared to its CSTO counterparts is its democratic trajectory. Armenia has consistently expressed its commitment to democracy, with officials frequently asserting that this democratic path will bolster national security. In contrast, according to Freedom House, all other CSTO member states are classified as not free, with severely restricted political rights and civil liberties for their citizens.

The member states of CSTO, except Tajikistan, also form the Eurasian Economic Union. Armenian authorities, primarily Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan, have stated several times that although Armenia has disagreements with the CSTO and Russia regarding the implementation of defense obligations, he hopes that Armenia will have productive cooperation with the EEU and that the agenda of the economic organization will not be politicized. Despite the fact that Armenian authorities have not hinted at leaving the EEU, Russian Deputy Prime Minister Aleksey Overchuk stated recently that the EU and EEU are incompatible. The strategic implications of this developing situation remain to be seen, but Armenia’s pivot will likely influence both its own national policies and also the broader geopolitical landscape of the region. International and domestic actors will be watching closely how this shift develops.

News Watch

Armenia, U.S. Hold Military Exercise as Defense Ties Expand

Armenia and the U.S. conduct the second joint Eagle Partner military exercise, marking growing defense cooperation between the two countries. Hovhannes Nazaretyan details the exercise's objectives, scale and international reactions.

Read moreRussia’s Soft Exit: Border Guards and Peacekeepers Withdraw

Russian peacekeepers recently withdrew from Nagorno-Karabakh, now under full Azerbaijani control, as did border guards at Armenia’s border with Azerbaijan and Zvartnots, Yerevan’s international airport, symbolizing Russia’s retreat from the South Caucasus.

Read moreEU and the U.S. Pledge to Support Armenia’s Resilience

A high-level meeting designed to support Armenia’s economic resilience took place in Brussels on April 5 and was met with criticism by Azerbaijan and Russia. Hovhannes Nazaretyan explains.

Read morePolitics

European Peace Facility’s First Assistance Measure for Armenia

Sossi Tatikyan explores the reasons behind the EU's decision to provide assistance to Armenia through the EPF, the significance of this measure, the diverse perspectives within Armenia and the ensuing hostile reactions from Azerbaijan and Russia.

Read moreArmenia’s Defense Diversification Gains Steam

While India and France have emerged as Armenia’s primary suppliers of military hardware over the past two years, Yerevan is also expanding its defense ties with other countries to enhance its security capabilities.

Read moreAzerbaijan’s and Russia’s Campaign of False Narratives Against the France-Armenia Partnership

The deepening France-Armenia partnership has spurred Azerbaijan’s disinformation campaign against France, escalating into a hybrid war. Sossi Tatikyan debunks these narratives, revealing their striking commonalities with Russian tactics.

Read moreUntangling Armenia’s Indian Arms Procurement

As the procurement of Indian weapons by Armenia has come under the spotlight, various Indian outlets, ranging from credible publications to blogs, have extensively and often speculatively covered Armenia’s arms acquisitions, underscoring the need to clarify the details. Hovhannes Nazaretyan’s investigation.

Read moreCSTO: Closer to Azerbaijan Than Armenia, Part I

Armenian experts were hardly under the illusion that the CSTO would fulfill its statutory obligations toward Armenia, given strong military and political ties between Azerbaijan and some CSTO members.

Read moreCSTO: Closer to Azerbaijan Than Armenia, Part II

The question of whether Armenia should remain a member of the Russian-led Collective Security Treaty Organization or withdraw continues to be debated in Armenian political circles. Armine Margaryan explains and offers a new perspective.

Read moreEVN Security Report

EVN Security Report: July 2024

There has been extensive debate about Washington’s strategic policy goals and growing investment in Armenia's security architecture. To understand the strategic framework guiding this engagement, the concept of “defense diplomacy” is introduced in this month’s security report.

Read moreAlso see

Of Republic, Order and Decay

A brief review of classical republican theory and Florentine political history to contextualize the challenges facing the Armenian Republic; not as a mere commentary on current affairs, but as a way of recasting Armenian history without renouncing what makes up our historical identity.

Read moreBaku’s Demand for Armenia to Amend Constitution Lacks Legal Credibility

The latest obstacle to a peace agreement between Armenia and Azerbaijan is Baku’s demand that Armenia amend its Constitution, specifically the preamble referencing the Declaration of Independence. Zaven Sargsian argues that Azerbaijan’s argument is deeply flawed.

Read more

Very well researched article!