There is significant interest in Syunik, Armenia, and several questions remain unanswered. For instance, is the United States interested in preserving Armenia’s sovereignty over the region, and, if so, why? The U.S. reportedly put an end to the heavy fighting of September 2022, and hosted Armenia and Azerbaijan for negotiations. Another nagging question is whether Russia wants Azerbaijan to have an extraterritorial corridor through Syunik. Although Russia has publicly denied supporting such a corridor, at least one high ranking Armenian official asserts that Russia is pressuring Armenia to provide one. To fully understand the situation in Syunik, we must also understand energy security in the European Union.

Prior to the war in Ukraine, the EU was heavily reliant on Russian natural gas. In 2021, the EU consumed roughly 397 billion cubic meters (bcm) of natural gas annually, about 83 percent of which was imported. Of that amount, the EU imported 155 bcm of natural gas from Russia, or about 45% of all EU gas imports.

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the EU’s import of natural gas from Russia was dramatically reduced. As of November 2022, it reportedly accounted for only 12.9% of the EU’s total natural gas imports. The EU is now facing an unprecedented energy crisis. While attempting to fill the gap from alternative sources, the EU has experienced a significant increase in its gas bill. The EU’s gas import bill reached close to EUR 400 billion in 2022 – more than three times the level in 2021.

Potential Alternatives to Russian Natural Gas

The EU’s efforts to reduce its dependence on Russian energy will be a challenging task. Russia has the world’s largest natural gas reserves, estimated at 38 trillion cubic meters, and the infrastructure to import natural gas to the EU The European Council on Foreign Relations warns that the EU will face significant challenges in achieving independence from Russian gas supplies, particularly in securing a stable gas supply from sources other than Russia. The International Energy Agency estimates that the EU may face a gas shortfall as high as 57 bcm in 2023, although the EU was successful at managing the cold weather needs for the year so far. Thus, the question arises as to who will fill this gap.

Iran may be an important and viable alternative for natural gas. With the world’s second-largest reserves, Iran possesses 32 trillion cubic meters of natural gas resources, accounting for around 16% of the world’s total. It is also one of the few countries capable of meeting most, if not all of the EU’s natural gas needs. However, transporting natural gas to the EU would likely pose geographical and geopolitical challenges.

Iranian Gas May Be a Viable Option if JCPOA Is Reinstated

If the U.S. and Iran can revive the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), or some version of it, and lift sanctions on Iran’s natural gas sector, Iranian gas could be an alternative.

Signed in July 2015, the JCPOA was a landmark accord between Iran and seven other nations: China, France, Germany, Russia, the UK, the U.S. and the EU. Under the JCPOA, Iran agreed to dismantle much of its nuclear program and allow for more extensive international inspections of its facilities. In exchange, Iran would receive a comprehensive lifting of all UN Security Council sanctions as well as multilateral and national sanctions related to its nuclear program, including progress on access in areas of trade, technology, finance, and energy. For example, the U.S. committed to end sanctions on, among other things, investment in Iran’s oil, gas and petrochemical sectors; the purchase, acquisition, sale, transportation or marketing of natural gas from Iran; and transactions with Iran’s energy sector.

The JCPOA remained in place for nearly three years. However, in 2018, President Trump withdrew the U.S. from the JCPOA. According to the New York Times, “Mr. Trump’s announcement drew a chorus of opposition from European leaders, several of whom lobbied [Trump] feverishly not to pull out of the agreement and searched for fixes that would satisfy [Trump].” The withdrawal was also condemned by public figures in the U.S., such as President Obama, who said that the withdrawal would “leave the world less safe, confronting it with ‘a losing choice between a nuclear-armed Iran or another war in the Middle East.’”

In 2021, when President Biden was elected, there was cautious optimism that the U.S. would return to the JCPOA. President Joe Biden indicated that the United States would return to the deal if Iran came back into compliance. Starting around April 2021, the U.S. and Iran began indirect talks to revive the JCPOA. It is generally agreed that in August 2022, Iran and the U.S. came close to reaching a deal to revive the JCPOA.

The talks ultimately stalled with both sides blaming the other. However, two subsequent events appear to have significantly hampered those talks. In July 2022, the White House claimed that Iran was planning to provide — or may have already provided — Russia with hundreds of drones for use in Ukraine. Then, in September 2022, nationwide protests broke out in Iran after a young Kurdish woman was killed while in the custody of the Iranian morality police. EU foreign policy chief Josep Borrell reportedly condemned Iran’s use of force and said all options would be on the table at the next meeting of EU foreign affairs ministers. U.S. envoy for Iran Rob Malley stated that the Biden administration was not going to “waste time” trying to revive JCPOA talks with Iran.

Is JCPOA Dead?

Despite statements to the contrary, important news emerged last month that the U.S. may be seeking to initiate talks with Iran over the nuclear deal using a new approach called the “freeze-for-freeze.” According to “ten Israeli officials, Western diplomats and U.S. experts with knowledge of the proposal,” the Biden administration discussed a proposal with the Europeans and Israelis for an interim agreement with Iran that would include some sanctions relief in exchange for Tehran freezing parts of its nuclear program.

While the scope of the “freeze-for-freeze” is currently unknown, the Iranians may present the lifting of sanctions on its energy sector as a win-win for the West and Iran. During the JCPOA revival talks in 2022, the Iranians expressed a keen interest in exporting gas to the EU. In September of that year, Iran’s Foreign Ministry spokesman Nasser Kanani stated, “Given Europe’s energy supply problems triggered by the Ukraine crisis, Iran could provide Europe’s energy needs if sanctions against it are lifted.” That same month, Iran’s Oil Minister Javad Oji reportedly offered to assist Europe with oil and gas deliveries, citing the exorbitant energy prices in the EU.

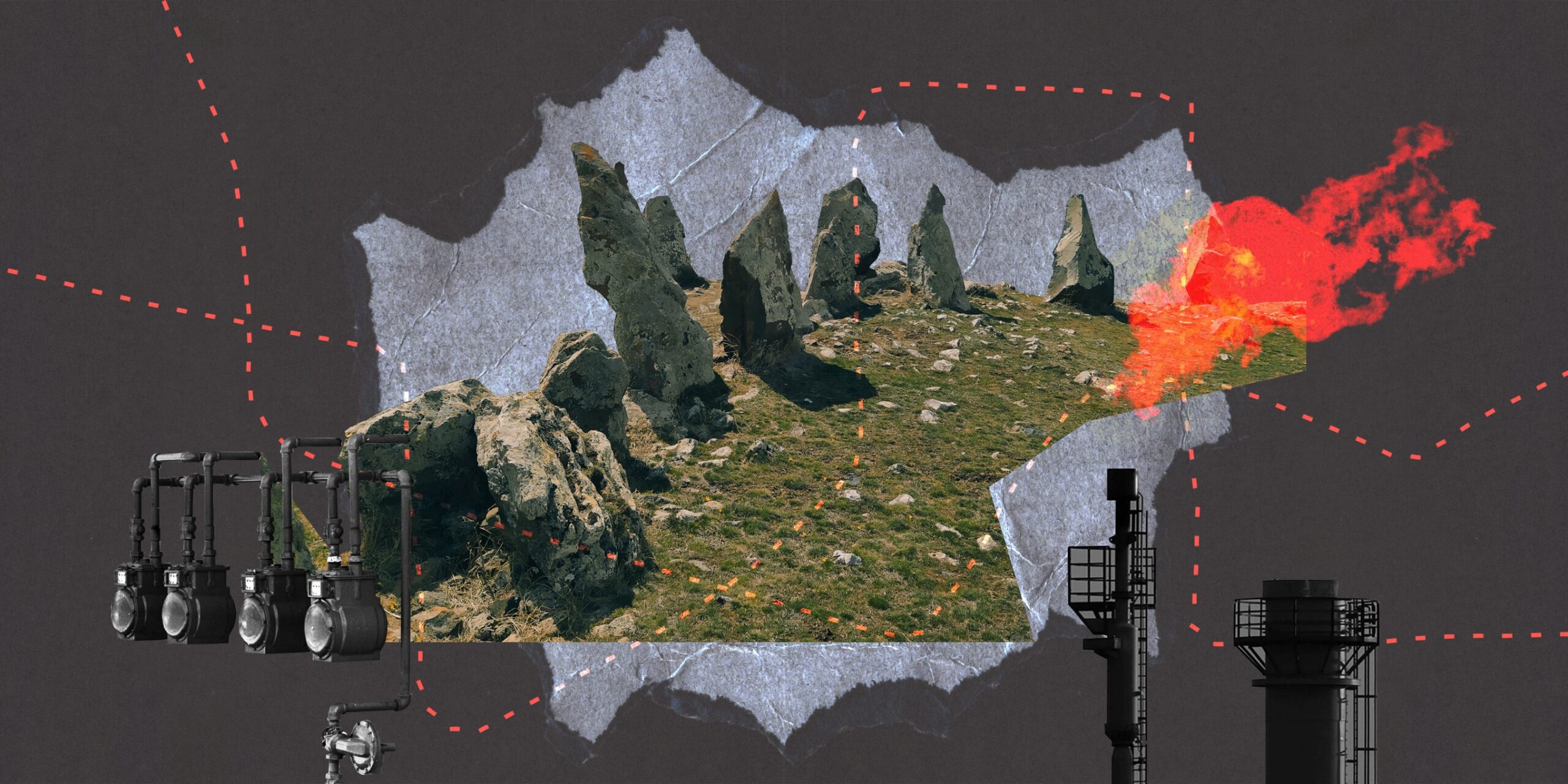

Armenia Could Be a Transit Route for Iranian Natural Gas

Assuming that the political challenges between the U.S. and Iran can be overcome, there seem to be four options for piping Iranian gas: (1) an Iran-Iraq-Syria pipeline; (2) an Iran-Turkey pipeline; (3) an Iran-Azerbaijan-Georgia pipeline; and (4) an Iran-Armenia-Georgia pipeline. Let’s explore each option.

Firstly, it is unrealistic to expect an Iran-Iraq-Syria pipeline to be constructed given the current conditions of Iraq and Syria. Much of northern Iraq, which is governed by the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), is in a state of turmoil. In fact, the KRG has been unable to extend its own pipeline network toward the border with Turkey due to tensions between the region’s two ruling families. Even if Iran were able to traverse Iraq, it would then have to traverse Syria, which is divided by various domestic and foreign forces, including the Russians, Turkish-backed militants, and Shia militias. According to The Washington Institute, while Bashar al-Assad’s forces control the majority of Syria’s territory they control only 15% of the country’s international land borders, with the rest divided among actors.

Furthermore, an Iran-Iraq-Syria pipeline was already attempted in 2011, then called the “Islamic Pipeline”, but ultimately failed to materialize due to the war in Syria and the crippling sanctions on both Syria and Iran. Therefore, the construction of an Iran-Iraq-Syria pipeline seems highly unlikely.

While an Iran-Turkey pipeline is theoretically possible, there are significant hurdles to its construction. Turkey is Iran’s regional competitor and is unlikely to strengthen Iran by giving it significant natural gas revenue. Additionally, the EU may not be keen to further rely on Turkey as a transit route. Several natural gas pipelines already pass through Turkey, and Turkey reportedly aims to become a gas hub for Europe. However, allowing Turkey, an unfaithful NATO ally, to achieve its goal of becoming a gas hub would mean the EU making the same mistake it did with Russia and moving its reliance from one autocratic nation (Russia/Putin) to another (Turkey/Erdogan).

Furthermore, even if the EU was undeterred by Turkey’s autocratic tendencies, it must still diversify its supply routes. The European Commission has stated that a key part of ensuring secure and affordable supplies of energy to Europeans means diversifying supply routes.

Finally, while the Iran-Azerbaijan-Georgia route could transport Iranian gas, it presents its own unique set of challenges. Azerbaijan’s relationship with Iran has deteriorated to its lowest point, with some commentators even predicting a military conflict. Azerbaijan is also interested in exporting gas to the EU, and has been exploring bringing Turkmen gas to Europe via the Trans-Caspian pipeline, along with Turkey. Although a Turkmenistan-Azerbaijan-Turkey pipeline has faced obstacles, including Turkmen reluctance and alleged Russian interference, it is unclear why the Turkic countries would be willing to help a future Iran get its gas to Europe.

Additionally, Azerbaijan currently lacks the pipeline capacity for Iranian natural gas. The Trans-Anatolian Pipeline (TANAP) and South Caucasus Pipeline (SCP) – running through Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey – have a maximum capacity of 25 bcm of gas per year (even after additional development), of which is some is already committed to Turkey (11 bcm) and Georgia (2.7 bcm). This means that Azerbaijan can transport only 12-13 bcm of natural gas annually to the EU. In 2021, Azerbaijan transported only 8 bcm of natural gas to the EU, and while it intends to increase that amount to 20 bcm by 2027, Azerbaijan is constrained by its own production and consumption. In 2021, Azerbaijan reportedly produced 43.9 bcm of natural gas, some of which is committed or consumed.

| Domestic Consumption | Amount |

| Azerbaijan | 12.37 bcm |

| Turkey | 11 bcm |

| Georgia | 2.7 bcm |

Assuming that the SCP and TANAP pipelines could be greatly expanded beyond their current capacity, at most only 16-17 bcm of Azerbaijani gas could be transported to the EU. Industry experts have reached similar conclusions, with one analyst stating that even if there is a similar increase in volume by 2027, Azerbaijan’s export potential to Europe will likely be around 15-16 bcm.]

An Iran-Armenia-Georgia Pipeline to the EU Could Be an Alternative

A future Iran-Armenia-Georgia pipeline could be a realistic and reliable option for the EU to fulfill its natural gas needs and diversify its sources. Armenia and Georgia are democratic countries that score relatively high in terms of freedom and democracy. In fact, Armenia and Georgia were recently invited to President Biden’s Summit for Democracy, while Turkey and Azerbaijan were notably absent. A pipeline from Iran to Armenia is geographically feasible, as evidenced by the fact that Armenia already has one pipeline from Iran, although its diameter was reportedly limited due to Russian pressure in the 2000s.

Relatedly, it appears both Russia and Iran have long been aware of a potential gas route from Iran to Armenia and on to the EU. In 2007, one analyst noted that Tehran has not abandoned its hopes to achieve a transit route for its gas into the South Caucasus and further into the EU, with Armenia as the first way station on that possible route, adding that, “Moscow, however, strongly opposes such a prospect.” As of 2019, Armenia reportedly stood ready to deliver Iranian gas to the EU. In February 2019, Armenia’s prime minister stated that, “Armenia is ready to conduct transit cooperation with Iran and be a transit country for Iranian gas.” While there are challenges to an Iran-Armenia-Georgia pipeline, it is an option that the EU and U.S. should keep open.

Azerbaijan Threatens to Occupy and Cut Off Armenia’s Southern Land Border With Iran

Since the conclusion of the 2020 Artsakh War, Azerbaijan has been demanding an extraterritorial corridor across southern Armenia. This would effectively cut Armenia off from Iran. What is more concerning is that the Azerbaijanis have proposed that the extraterritorial corridor be overseen by the Russian Federal Security Service (or FSB). Azerbaijan is not even attempting to hide its intentions. On April 21, 2021, Azerbaijan’s President Ilham Aliyev stated on public TV, that “the creation of the . . . corridor fully meets our national, historical and future interests. We are implementing the . . . corridor, whether Armenia wants it or not. If Armenia wants, we will solve this issue more easily. If it does not want it, we will solve it by force.”

Aliyev repeated much of this most recently on January 3, 2023, stating that the corridor is a “historical necessity”. Azerbaijan is currently occupying at least 120 square kilometers of Armenia’s sovereign and internationally recognized territory.

If Azerbaijan is allowed to invade and occupy Armenia’s southern border, Russians and the Azerbaijani-Turkish tandem would directly control Iran’s access through Armenia to the EU, interfering with what could be a critical transport route for Iranian natural gas to the EU.

Who’s on Whose Side?

If this is the case, then it becomes clear which nations support an extraterritorial corridor through Syunik. On one hand, Armenia, Iran, the EU, and the U.S. should be against such a corridor controlled by the FSB. A stable and secure EU is vital to U.S. national interests. Additionally, the EU’s energy security is crucial for its stability.

Meanwhile, Azerbaijan, Turkey, and Russia are likely in favor of such a corridor. Energy is a key pillar of Russia’s foreign policy. As indicated by an EU study, although “Russia will never admit when its energy policy decisions are driven by geopolitics . . . when considering a number of instances of supply disruption or pricing disputes, a geopolitical pattern emerges.” In other words, Russia “has shown a willingness to abuse its dominant market position in support of foreign policy goals . . . .” If Russia were to have unfettered control of an extraterritorial corridor through Syunik, it could likely prevent an Iran-Armenia-Georgia pipeline. Russian concerns about the EU importing Iranian gas are not new. According to one expert, such concerns have influenced Russia’s actions “in diverting Iran’s gas exports away from Europe.”

Regarding Azerbaijan and Turkey, a Syunik corridor would significantly further their national interests. It would be an economic victory as Azerbaijan would have uninterrupted transit to Turkey. It would be a political victory for Erdogan and Aliyev, as the Turkic world would be linked by land. However, it would diminish Armenia, and to a lesser extent, Iran.

EVN Security Report

EVN Security Report: May 2023

Armenia’s vast mines have never been part of its security architecture, nor has the potential securitization of this sector ever been considered a fundamental cornerstone of building alliances or strategic partnerships. Mining-for-security should not be qualified as a political act, but rather, a fundamental security act, Nerses Kopalyan writes.

Read moreExamining the Context

EVN Security Report, May 2023

Opinion

Is Peace Possible in the Absence of Aliyev’s Self-Restraint?

Intoxicated by his success on the battlefield, Ilham Aliyev is betting on further exercises in uncontrolled power politics, combining unlimited claims to Armenia and Artsakh with open challenges and threats to international players.

Read moreThe New Golden Age of Armenophobia

The West has its “causes célebres” where repressive language against minorities would be countered with outrage. Minorities less propitiously situated in the West’s configuration of interests are worthy of an embarrassed silence. Kevork Oskanian explains.

Read moreDealing With the Devil: Does Aliyev Really Want Peace?

Armenia has fulfilled nearly all its obligations under the tripartite ceasefire statement that brought the 2020 Artsakh War to an end. Azerbaijan has not upheld its side of the bargain, nor does it seem intent to. Karena Avedissian explains.

Read morePolitics

Can a Piece of Paper Bring Long-Lasting Peace?

Without a clear recognition of the reality on the ground, especially Azerbaijan's obstructionist behavior, and without substantive enforcement instruments provided by international actors, a piece of paper cannot serve as a real peace deal, Tatevik Hayrapetyan writes.

Read moreWith Russian Inaction, Armenians Look for A New Ally

Russia's perceived unwillingness to assist Armenia and fulfill its treaty obligations during times of crisis has compelled both the Armenian government and the general public to seek new allies. France, the U.S., EU and Iran have emerged as potential frontrunners.

Read moreThe Italian Media’s Relation With Armenia and Azerbaijan

Although Italy and Armenia have a long history of ties, Italy’s current economic interests and choice of strategic partners leave little room for maneuver in support of Armenia or Artsakh.

Read moreOld Neighbors, New Realities

Iran will never accept any Azerbaijani military or political control of southern Armenia. While Tehran is pursuing a policy of strategic patience vis-à-vis Azerbaijan, it does have red lines that, if crossed, would likely produce a swift reaction.

Read more

The US and NATO are primarily interested in taking Armenia, Russia’s sole ally in the Caucasus, out of Russia’s orbit.

In this way, the US and NATO would own the Caucasus and Caspian, and from there it’s on to Central Asia.

Too bad Russia is punishing Armenia instead of helping to protect it.