Following Azerbaijan’s September 2023 attack against and ethnic cleansing of Artsakh (Nagorno-Karabakh), the issue of the preservation of Armenian monuments has again become a hot topic. Simon Maghakyan, an academic and investigative researcher best known for his pioneering exposé of Azerbaijan’s covert erasure of Nakhichevan’s Armenian past spoke with EVN Report and provided updates and insights.

EVN Report: What were the consequences of Azerbaijan’s September 2023 invasion of Nagorno-Karabakh, particularly in terms of Armenian cultural heritage?

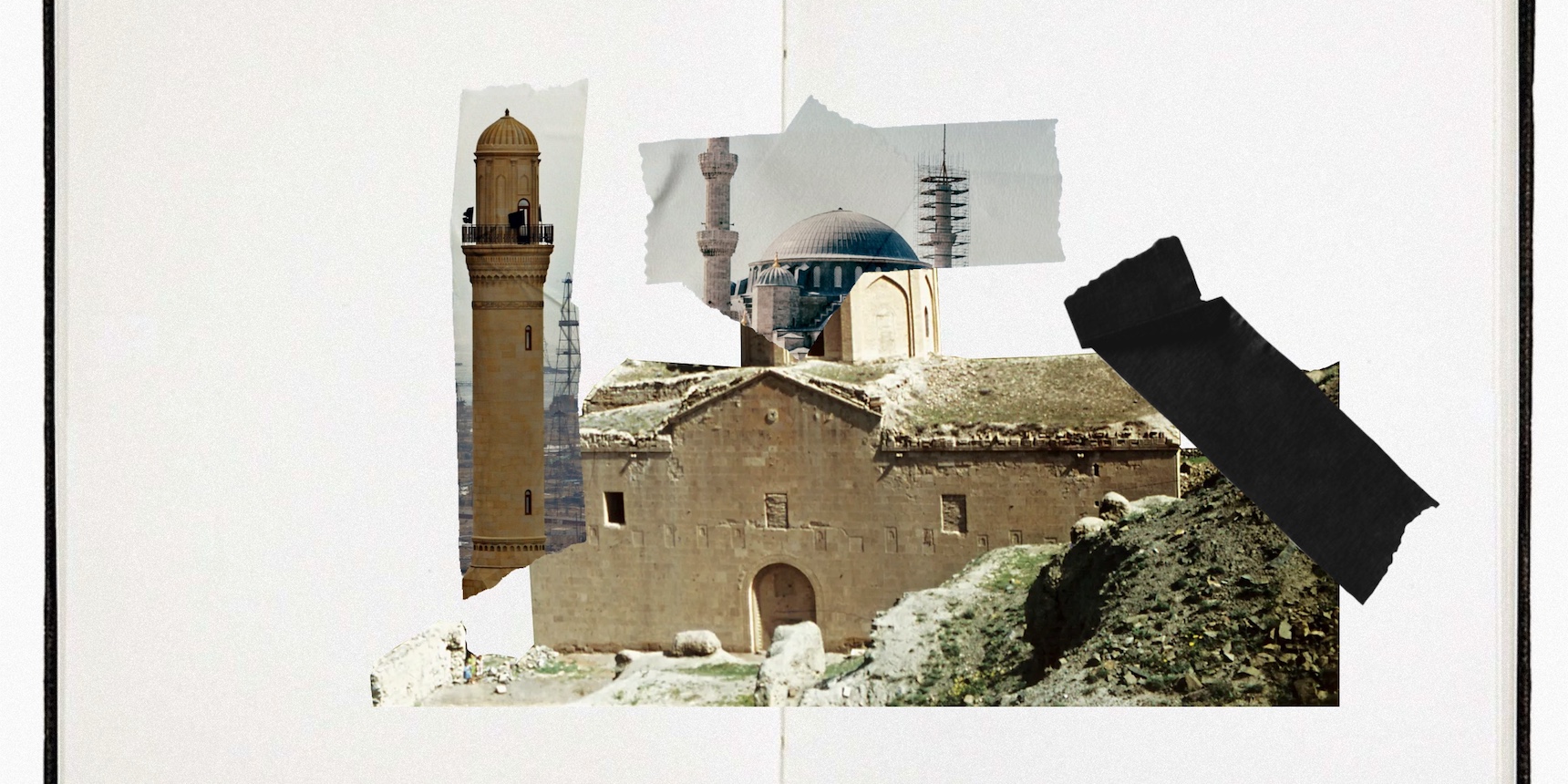

Simon Maghakyan: Azerbaijan’s September 2023 “final solution” invasion of Nagorno-Karabakh resulted not only in the region’s complete ethnic cleansing but now has many worried about the vast Armenian cultural heritage left behind. An estimated 500 historical sites that house as many as 6,000 monuments in the wider Artsakh region are now under the control of a government known for its zero tolerance against Armenian history. The fears are grounded in rock-solid facts in another historically Armenian region, Nakhichevan, where between 1997-2006 Azerbaijan eradicated the entire known inventory of Armenian Christian sites consisting of an estimated 89 churches, 5,840 khachkars (stone-crosses), and over 22,000 tombstones. And not only.

Since the 2020 war, Azerbaijan has destroyed cemeteries and churches, as documented by Caucasus Heritage Watch and Monument Watch, and further dismantled Shushi’s iconic Ghazanchetsots Cathedral that it bombed twice during military operations. Add to this Azerbaijan’s propaganda that the Armenian monuments of Nagorno-Karabakh are either non-Armenian or “artificially aged forgeries,” and you have a disaster recipe. But not all hope is lost, especially if there can be constant and comprehensive monitoring of those sites.

Q: How does the lack of comprehensive documentation contribute to concerns?

SM: The Cornell University-based Caucasus Heritage Watch has a monumental satellite monitoring program that issues periodical alerts and quarterly reports based on satellite imagery. We are lucky to have such a program. But remote-monitoring has technical limitations. If Azerbaijan, for instance, were to polish out Armenian lettering off churches, satellites would not capture such an end-result. Also, fresh satellite images are expensive to obtain, so even sites that can be spotted from space cannot be monitored on a perpetual/real-time basis.

Since Azerbaijan is not allowing on the ground monitoring, and satellites can’t document everything, a mix of genuine concerns and lack of instant monitoring creates ground for misinformation.

Q: How can misinformation hinder preservation efforts?

SM: Accurate information and frank analysis are necessary for any hope of preventing a Nakhichevan scenario in Nagorno-Karabakh. In the early 2000s, for example, exaggerated reports on the scope of Azerbaijan’s destruction of the Djulfa cemetery proved unhelpful: when the final erasure started in December 2005, most of the cemetery was still salvageable (even though the khachkars had been toppled). A similar fatalist narrative is often presented on the state of Armenian sites in Turkey: indeed, most monuments have been severely damaged, if not outright destroyed (and even the monuments under the Istanbul Patriarchate’s direct protection are targets of hate, as recently documented by USCIRF), but when a crumbling heritage is misrepresented as having been “completely destroyed,” avoiding the actual latter scenario becomes unnecessary.

While misinformation (unlike disinformation) isn’t intended to mislead, it is more than often a byproduct of lack of information and is still hurtful to the cause of preservation. We see a few such examples concerning the heritage of Artsakh.

Q: Can you elaborate?

SM: There are about five narratives popular on Armenian social media on Azerbaijan’s erasure of Armenian monuments that are misleading. These can be summarized as: 1) Azerbaijan is destroying everything, 2) Azerbaijan is converting churches to mosques, 3) Azerbaijan is just as bad as Turkey, 4) Azerbaijan has always destroyed Armenian culture, and 5) There are either no solutions or magical solutions.

Q: Is Azerbaijan not keen on destroying all Armenian heritage under its control?

SM: The ultimate goal of Azerbaijan’s current regime is indeed complete erasure. But at the moment it is not in a position to do so, at least not right away. There are three reasons for this.

First, Azerbaijan wishes to create an international impression of being a responsible actor, so it must contain its behavior for global audiences, especially in light of the recent ethnic cleansing.

Second, in December 2021 the International Court of Justice (ICJ) ordered Azerbaijan, in its provisional (temporary) decision, to “punish and prevent” destruction of Armenian monuments. Since this decision Azerbaijan has acted with relative restraint: there have been destructions of several cemeteries and churches, but not a large-scale erasure of everything. This means that there is hope that Azerbaijan may fundamentally limit its destruction for a period of time—until the anticipated final International Court of Justice decision (to decrease chances of a strong permanent court order against it). However, since the final decision may arrive as early as late 2025, this anticipated restrained behavior might be of temporary nature. An intriguing example of Azerbaijan’s restrained behavior is a satellite report, released in early November 2023 by the Caucasus Heritage Watch, which suggests that Azerbaijan may have “rebuilt” a church (Surb Sargis of Mokhrenes, Hadrut) that it destroyed after the ICJ provisional decision. That Azerbaijan would designate this church “Caucasian Albanian” (aka non Armenian) is another story. Nonetheless, this recent “rebuilding” shouldn’t give us too much hope, since during the same period Azerbaijan damaged another church in Shushi under the guise of development.

Finally, Azerbaijan has become a victim of its own propaganda: for decades the jewels of Artsakh heritage—from Gandzasar to Amaras to Dadivank to Tsitsernavank to Gtichvank—have been proclaimed “Caucasian Albanian”—aka proto-Azerbaijani, using this imagined connection to justify its claims to the region. It would be nearly impossible for Azerbaijan to completely destroy these prominent sites right away, given the publicity it has itself given to them through years of revisionist propaganda. Alas, this is mostly true for a handful of monuments: Armenian khachkars (intricately carved cross-stone stelae that typically function as headstones), cemeteries, and lesser-known churches are already targets of erasure, as anticipated. Many key Armenian khachkars, including the world’s oldest dated khachkar from 866 (in Vaghuhas village), were not evacuated after the recent invasion.

Q: Are reports of conversions to mosques accurate?

SM: No. Let me first note that not a single Armenian church has been turned into a mosque by the Aliyev regime in Azerbaijan. This may sound counterintuitive but a conversion—while also being an act of symbolic violence and erasure—presupposes a degree of respect: the Azerbaijani government simply does not consider Armenian churches worthy of becoming mosques.

Let’s take a closer look at the evidence. So far two Artsakh churches have been presented as being converted to mosques. First, the church in Lachin, constructed in the 1990s, is supposedly being turned into a mosque. This narrative is based on a proposal by a non-governmental group in Azerbaijan. It is not out of the question that the church may be turned into a mosque, but there is no evidence to pinpoint to that policy for the time being. On the contrary, it is more likely that the Lachin church will be turned into an anti-Armenian museum, as Azerbaijan is reporting the construction of an “occupation museum complex” in that city.

The conversion narrative is also based on photographs of Shushi’s Ghazanchetsots cathedral showing the dismantled conical dome. This destruction happened in early 2021 during a pretend “renovation” following the bombing of the cathedral during the 2020 war. The “renovation” started and stopped with the unnecessary dismantling of the dome, and the scaffolding is still around. Of course, it is understandable that individuals suspect that a scaffolding would be constructed for something more substantial than destroying a dome. It is likely that Azerbaijan hasn’t made a final decision with this Cathedral, but mosque conversion does not seem to be on the table. Then why was the dome destroyed? For a specific reason: so that it would resemble the post-1920 pogrom appearance of the Cathedral, just as it existed in the Soviet era.

I should note that the mosque conversion narrative was popularized at a hearing in the U.S. Congress in early summer 2023. This was based on no evidence except the speaker’s knowledge that Turkey has done the same. Unfortunately, others have been repeating the misinformation that Armenian churches are being turned into mosques—without any evidence. This reflects a foundational misunderstanding of the genocidal racism that the Aliyev regime has against Armenian heritage: it’s worth repeating that this regime does not consider Armenian churches worthy of becoming mosques. Unfortunately, the trauma of the Armenian Genocide has made many believe that Turkey’s treatment of Armenian history (which has included conversions) is worse than—or is at par with—what Azerbaijan does, which is not the case.

Q: How does Azerbaijan’s treatment of Armenian heritage differ from Turkey’s?

SM: There is a popular perception in Armenian communities, especially in the Diaspora, that Azerbaijan is just as bad as Turkey, but this is not the case. Turkey has destroyed and damaged most Armenian heritage sites through various processes, yet many structures still survive. Azerbaijan, on the other hand, has completely eradicated the entire Armenian Christian cultural landscape in Nakhichevan. Armenian anger at Turkey due to the Genocide should not be reason to misrepresent the partial erasure of Armenian heritage in Turkey as a complete erasure: many sites still exist (though barely so, since the government encourages systematic looting and destruction), and there is still opportunity to safeguard them; while the same doesn’t exist in Nakhichevan. Also, as noted above, Turkey has converted many Armenian churches to mosques, while Azerbaijan has never done the same. To be clear, Azerbaijan has constructed mosques on the plots of flattened Armenian churches, including in Agulis and Abrakunis in Nakhichevan, but that is not a conversion. Much more can be said on the similarities and differences of how Turkey and Azerbaijan treat Armenian heritage, especially how Azerbaijan has nationally securitized Armenian heritage, and used its erasure as performance legitimacy. This is part of my PhD research, but I don’t want to get too academic here. The takeaway is this: let’s be accurate and frank in our assessments, and steer away from unhelpful generalizations like “Azerbaijan always destroyed Armenian culture.” Unfortunately, physical cultural destruction doesn’t require decades to carry out.

Q: So it hasn’t always been an Azerbaijani policy to destroy all traces of Armenian culture?

SM: Let’s break down this question into theoretical and physical erasure. Starting with destalinization, which allowed for stronger “national” cultural expressions in the Soviet Union, the official Azerbaijani historiography has denied the presence of ancient Armenian and Georgian churches on the territory of Azerbaijan, instead relabelling these sacred structures as “Caucasian Albanian,” aka “proto-Azerbaijani.” So, if we are speaking about theoretical erasure, the answer is yes. However, systemic and systematic physical erasure in Nakhichevan only started in 1997, and lasted less than a decade, with the active phases constituting just a few combined years. This means that the narrative that Armenian heritage in Azerbaijan has been destroyed “over decades” is incorrect.

Q: Can you elaborate?

SM: The active phases of the statist erasure in Nakhichevan happened in just a few years: 1997-1998 (blasting off majority of churches and bulldozing of cemeteries) and 2005-2006 (final destruction of Djulfa and several overlooked churches and other cemeteries). These timelines are deduced from Azerbaijani and Iranian sources: including Akram Aylisli’s 1997 eyewitness telegram that dates the start of the destruction to no later than early June 1997; the 75th Anniversary of Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic, which was marked in 1999 with an emphasis on how the region was exclusively home to Turkic culture; the Dec. 6, 2005 decree by Nakhichevan’s satrap Vasif Talibov that ordered a complete “passportization” of all monuments (followed by mid-December 2005 eyewitness videography from Iranian territory of the destruction of Djulfa); the official 2008 publication Encyclopedia of Nakhchivan Monuments that confirms that the Dec. 6, 2005 decree intended to “prove” that there are no Armenian monuments, and the 2007 updated map of all monuments on the territory of Azerbaijan that no longer featured a single Armenian church (even under the label of “Caucasian Albanian”) in Nakhichevan.

I realize this is overwhelming information and that we would need hours to discuss and break down each of those points. But here is the takeaway: it’s vital to acknowledge that the active phase of the destruction of Armenian heritage in Nakhichevan was only a matter of just a few combined years: Not underscoring the statist, systematic, and systemic nature of the erasure in Nakhichevan (such an orchestrated campaign could not have lasted decades) undermines the reality of what happened and how it impacts the present and the future. Precision is one of the keys to prevention.

Q: Which brings us to solutions. You mentioned that there is a key misperception on this matter. What do you mean?

SM: Unfortunately, we often hear that “Nothing can be done, except by the international community,” which is the thinking that there are either magic solutions, or no solutions at all.

A part of this misunderstanding is that Armenians have no agency. Yet the reality is different, Armenians not only have agency but also responsibility in this process. For example, even if something meaningful happened internationally (such as the final International Court of Justice decision requiring long-term preservation of Armenian sites), it would still take active work by Armenians (by the Armenian government and non-governmental stakeholders) to ensure enforcement. Simply demanding from “the international community” to do something isn’t how this works. For example, people assume that UNESCO, which is not an all-powerful organization, can easily “prevent destruction.” Enforcement of international law is voluntary. Also, UNESCO is an autonomous body, composed of member states that drive the decisions. Yes, it has been co-opted by Azerbaijan in the past, but even a non-corrupt UNESCO can’t deliver wonders, especially without Armenian engagement. But the latter shouldn’t be limited to “working with the world.” In fact, global outreach should be just one of a multifaceted approach.

Q: So, what should that approach look like?

SM: The short answer to preventing a Nakhichevan scenario in Artsakh is giving Azerbaijan reasons not to destroy Armenian heritage. In theory, this can be done in two paradigms. One, in the short term, is to raise the cost of destruction: sanctions, bad press, international engagement, legal accountability pursuits, etc. Two, in the mid- to long-term, are to incentivize preservation: suggest economic prospects to Azerbaijan through Armenian pilgrimages, help Azerbaijan to perceive cultural diplomacy as a way of increasing soft power, and work with Azerbaijani civil society/independent academia to advocate for preservation. I know that the latter scenarios are unrealistic.

But consider this. The prevention of Nakhichevan’s scenario in Nagorno-Karabakh must start with understanding the underlying reasons of the destruction, which are the marriage of authoritarianism and securitization, but also lack of stakeholder connections (through monitoring and Armenian presence, even as pilgrimages). Unfortunately, many of the discussions underline the role of external factors, with little appreciation for the complexities of these processes. Much of the discussion always neglects Armenian agency, Armenian responsibility to prevent further erasure. I think this is a mistake and a recipe for self-fulfilling prophecies. Armenian stakeholders should leave no stone unturned in the drive for preservation. Armenian institutions, particularly the Apostolic Church, can play an important role. The Mother See, for example, should initiate a process for the recognition of the Artsakh Diocese by Azerbaijan. I realize how painful this would be, but not as painful as the entire Armenian heritage being wiped out in Artsakh, as it happened in Nakhichevan.

Q: Besides following you on Twitter/X and reading your analyses in TIME Magazine, where can our readers get further information and updates?

SM: There are three key organizations to follow and support: Caucasus Heritage Watch (caucasusheritage.cornell.edu), Monument Watch (monumentwatch.org), and Research on Armenian Architecture’s Artsakh Historical Monuments (artsakhmonuments.org)!

November on

EVN Report

Armenians of Jerusalem: Facing an Existential Threat

Are the future prospects of the Armenians in the Holy City, whose rich heritage is a cherished part of the diaspora, doomed? Despite their presence in Jerusalem dating back to the 4th century AD, during the early days of Christian pilgrimages, the current situation poses a significant threat.

Read moreLiving in Russia’s Long Shadow

Armenia’s recent turn away from Russia has sparked European hopes that the country could finally join the West. But that’s not the whole story. Karena Avedissian explains.

Read moreHealth, Women and War

With women and girls making up over half of the displaced people from Artsakh, what kinds of health and safety risks are they facing, and who is there to help?

Read moreA Dictator’s Parade Celebrating Ethnic Cleansing

Despite their differences, Russia, the EU and the U.S. all came together days before the Azerbaijani attack on Artsakh to ensure aid could reach the besieged population. Why did Aliyev risk going against them? Or did he? Tatevik Hayrapetyan presents a thought-provoking analysis.

Read moreTurkey’s Syrian Mercenaries in Azerbaijan: A Chronicle

Thousands of mercenaries from Syria were deployed by Turkey to Azerbaijan during the 2020 Artsakh War. In one of the most comprehensive reports on the use of mercenaries to date, Hovhannes Nazaretyan provides extensive background, evidence and international reactions.

Read moreUnbridled Horrors: A Long Way From Solferino

International Humanitarian Law constitutes a critical set of rules with the purpose of mitigating the humanitarian impact of armed conflicts. It has never set out to eradicate all human suffering during conflicts and violations, heinous as they are, do not render the law null and void.

Read moreA Critique of International Law: An Armenian Perspective

The Armenian public’s expectations and perceptions of international law has played a weighty role in the nation’s life. As Armenia has grappled with geopolitical challenges and crises, the role of international law has often been thrust into the spotlight, evoking both hope and frustration. Davit Khachatryan explains.

Read moreBetween Ownership and Neglect, Part 2: Aram’s House

The home of Aram Manukyan, widely recognized as the founder of the First Armenian Republic, located on 9 Aram Street in downtown Yerevan, continues to be abandoned and dilapidated and its future uncertain.

Read moreBetween Ownership and Neglect, Part 1: MFA Building

In the first of a series of articles about privatized and abandoned historic buildings in Armenia’s capital, Hovhannes Nazaretyan looks at the privatization process and current condition of the former Ministry of Foreign Affairs building in Yerevan’s Republic Square.

Read more