In the past decades, Armenia has achieved significant progress in utilizing renewable energy sources, primarily through hydropower, which has contributed between a quarter to a third of the country’s energy output. Despite this progress, the majority of Armenia’s electricity still comes from non-renewable sources. Last year Armenia produced 8,907.9 GWh of electricity, up 16% from 2021. The vast majority came from thermal power plants in Yerevan and Hrazdan (43.5%) and the Metsamor Nuclear Power Plant (32%).

Hydropower accounted for 21.8%, while solar stood at 2.7% and wind power at just 0.02%. Overall, renewable sources (hydro, solar, wind) combined generated 2,183 GWh or 24.5% of the total. Armenia exported 17.3% of the total electricity output to Iran and Georgia.

Renewable energy inevitably has a political side to it. In its recent resolution on EU–Armenia relations, adopted on March 15, the European Parliament called on the Armenian authorities to “take crucial steps to accelerate the development of renewable energy, increase energy efficiency and diversify energy sources, taking into account that natural gas imports from Russia still represent over 80% of Armenia’s gas imports, as well as the bilateral cooperation between Armenia and Iran on energy exchange.” Earlier, in 2017, when it signed the Comprehensive and Enhanced Partnership Agreement (CEPA) with the EU, Armenia committed to enhancing the security and safety of the energy supply, including by promoting the use of renewable energy sources.

Armenia’s progress in renewables came from two sources: small hydro and solar. However, wind power and other types of renewable energy are still not economically feasible at this time.

Solar

Armenia’s Public Services Regulatory Commission, the country’s utilities regulatory body, reported that as of the beginning of this year, there were 60 utility-scale solar farms operating in Armenia, with a combined installed capacity of 204.8 MW and an average annual generation of 444.8 GWh. These solar farms are concentrated in Aragatsotn (accounting for 45.3% of the installed capacity), Gegharkunik (29%), and Vayots Dzor (20.5%). Together, these three regions contribute nearly 95% of Armenia’s total installed solar capacity.

The installed capacities of Armenia’s 60 solar farms range from 64.91 kW to 5,000 kW (5 MW). The majority (32 of 60) are at the upper range (5 MW), which seems to be the preferred size.

The first license for a solar farm in Armenia was granted in November 2017, but only 12 were built in the first three years. Last year saw a significant surge in growth, with more than half of all solar farms (34 of 60) built in 2022 alone. These 34 solar farms account for 75% of the total capacity, providing 154 out of 204.8 MW.

Distributed Generation

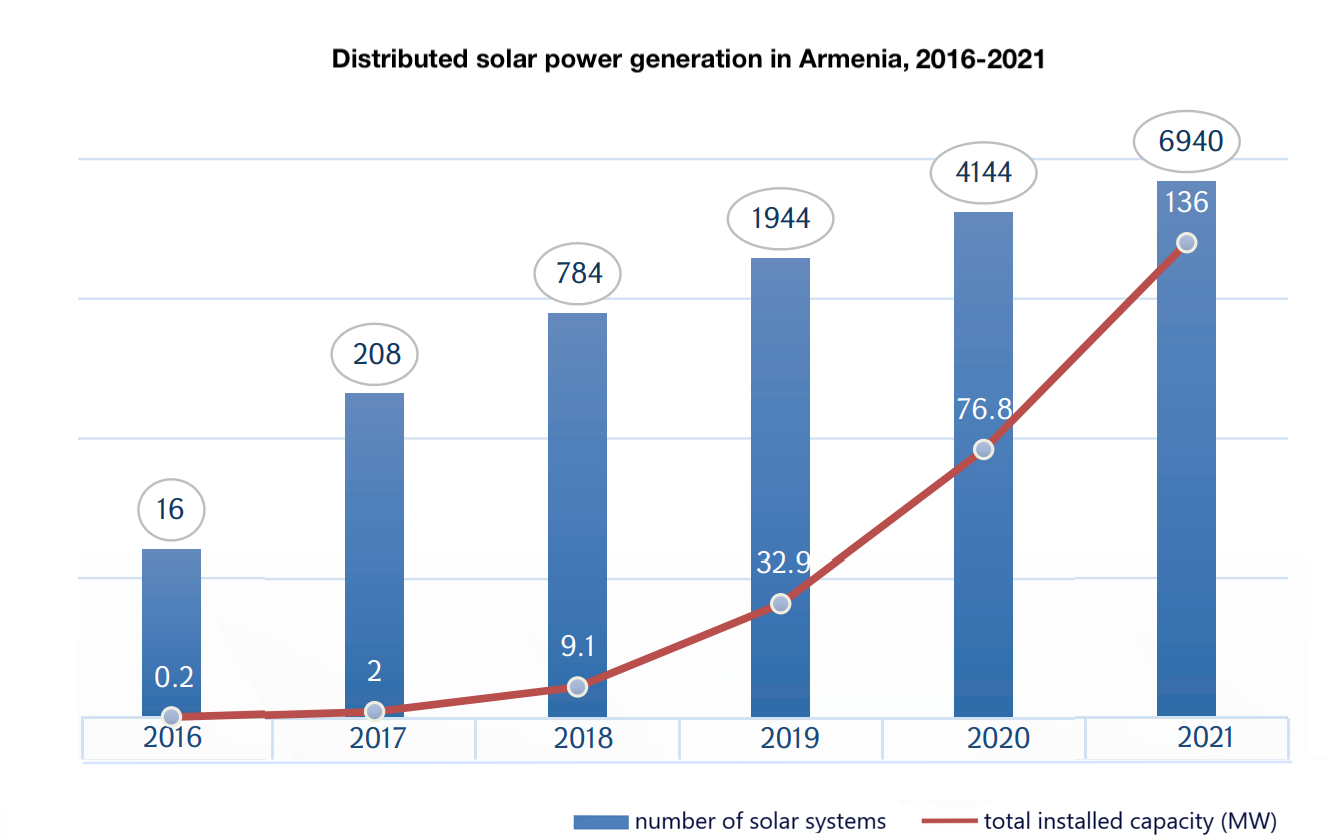

In addition to the 204.8 MW capacity of utility-scale solar farms, there are further 11,122 grid-connected solar power systems (like rooftop panels) with a combined capacity of 207.5 MW as of March 1, the Public Services Regulatory Commission told EVN Report.

Data provided by the commission reveals an incredible growth in distributed generation in the past several years. By the end of 2019, the installed capacity of distributed solar generation stood at just 32.9 MW, spread across almost 2,000 systems. In two years, the combined capacity more than quadrupled to reach 136 MW across almost 7,000 systems at the end of 2021.

This chart shows the combined capacity in MW (in red line) and the number of solar systems (in blue bars).

Source: Public Services Regulatory Commission

In 2017, Tamara Babayan, a sustainable energy expert, estimated the potential of Armenia’s distributed solar power at 1,280 MW and almost 1,800 GWh in annual generation. This estimate is based on the assumption that half of the available rooftop area in Armenia is developable, indicating that there is significant potential for further growth in the sector.

Future Plans

In its long-term strategy (up to 2040) for the energy sector, adopted in January 2021, the Armenian government identified the maximum utilization of renewable energy potential as a priority. In consideration of both local resources and global trends, the government has prioritized solar as the preferred source of renewable energy over other alternatives. By 2030, the government intends to increase electricity generation to 12,000 GWh and electricity exports to 5,000 GWh compared to 7,600 GWh and 1,250 GWh in 2019, respectively. It hopes to increase solar energy generation to 1,800 GWh to make up 15% of the total by then. To meet the goal, around 1,000 MW of solar power capacity needs to be installed, including distributed generation.

There are currently two large solar farms either under construction or in the planning phase. Together, they will have a capacity of 255 MW and generate an estimated 430 GWh annually.

The first, Masrik-1, is located near the village of Mets Masrik in the Vardenis area of Gegharkunik region. Once completed, it will have a capacity of 55 MW and generate 110 GWh annually. Originally announced in 2017 with a planned completion date of 2019, the project faced delays due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the 2020 Artsakh War, resulting in a new target completion date of 2024. Despite having only commenced construction last year, the project has experienced some setbacks and disruptions. It is being built by a Spanish-Dutch consortium, selected in 2018, that is ultimately owned by Abdul Latif Jameel, a Saudi holding company. The total investment for the project amounts to $60 million.

The second plant, Ayg-1, will have an installed capacity of 200 MW and generate 320 GWh annually. It will be built near the town of Talin, in Aragatsotn region, by Masdar, an Emirati state-owned renewables developer, with an investment of $174 million. Masdar will own 85% of the project company, while the government will hold 15% through the Armenian National Interests Fund (ANIF). Masdar was selected in July 2021 and it signed a government support agreement in November 2021. Its completion was initially planned for December 2023, but ANIF has indicated 2025 as the start date after construction in 2023 and 2024.

The larger cooperation with Masdar includes another 200 MW solar farm, named Ayg-2. It is expected to be built near the town of Yeghvard in Kotayk and the village of Nor Yedesia in Aragatsotn. ANIF says it will include energy storage. Initial plans estimated an investment of $150 million and a completion date of December 2024, but it has not yet entered the planning phase and it will likely be postponed.

Apart from these, the government’s long-term action plan also aims to build five utility-scale solar farms with a combined capacity of 120 MW and annual generation of 192 GWh by December 2024 and small (below 5 MW) solar farms with a combined capacity of 315 MW by 2029 that would generate 326 GWh annually. The government aims to attract $340 million investment for the latter.

Wind

Armenia’s wind energy sector is minuscule. The entire country has just four wind farms with an installed capacity of 4.23 MW and an average annual generation of 3.97 GWh. One of these farms, in Sotk, eastern Gegharkunik, with an installed capacity of 1.32 MW, stopped operations after Azerbaijani forces advanced in the area following the ceding of the Kelbajar district to Azerbaijan on November 25, 2020 after the 2020 Artsakh War. A proposed wind farm in Gavar, the regional center of Gegharkunik, was granted a license to operate in 2018, but has not yet entered the construction phase. If built, the 4 MW farm will double Armenia’s total capacity of wind power. Its annual generation is estimated at 10 GWh.

In its long-term strategy, the Armenian government has aimed to increase installed wind energy capacity to up to 500 MW between 2025 and 2040 if there are competitive price offers. The government has stressed the latter point, saying that its support to private businesses will be conditioned by competitive price offers.

A 2003 study by the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) estimated Armenia’s land areas with “good-to-excellent” wind resource potential to be around 1,000 km². With a conservative assumption of 5 MW per km², the authors noted that the area could support almost 5,000 MW of potential installed capacity. The number jumps to 11,000 MW if areas with moderate wind resource potential are considered. Another study in 2010 by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) assessed the “total wind energy potential for grid-connected plants” to be over 1,000 MW, but only half of that, around 500 MW, with annual generation potential over 1,000 GWh, is “currently considered feasible.”

The USAID study pointed out that wind energy cost in Armenia is “substantially higher than existing sources,” but stated that these costs “will never increase since there is no variable imported fuel cost.” The study added that installed costs in Armenia are about 20% higher compared to similar projects in Europe due to “remote siting, lack [of] construction experience and infrastructure, and the generation potential is lower due to elevation factor and lower air density.”

According to a study commissioned by the Konrad Adenauer Foundation, Armenia’s roads, including fluctuations in elevation, make them problematic and unsuitable for transporting large turbines (generating 1.5 to 3 MW) and blades (up to 52 meters long). There are ongoing attempts to set up domestic production of small turbines.

Hydro

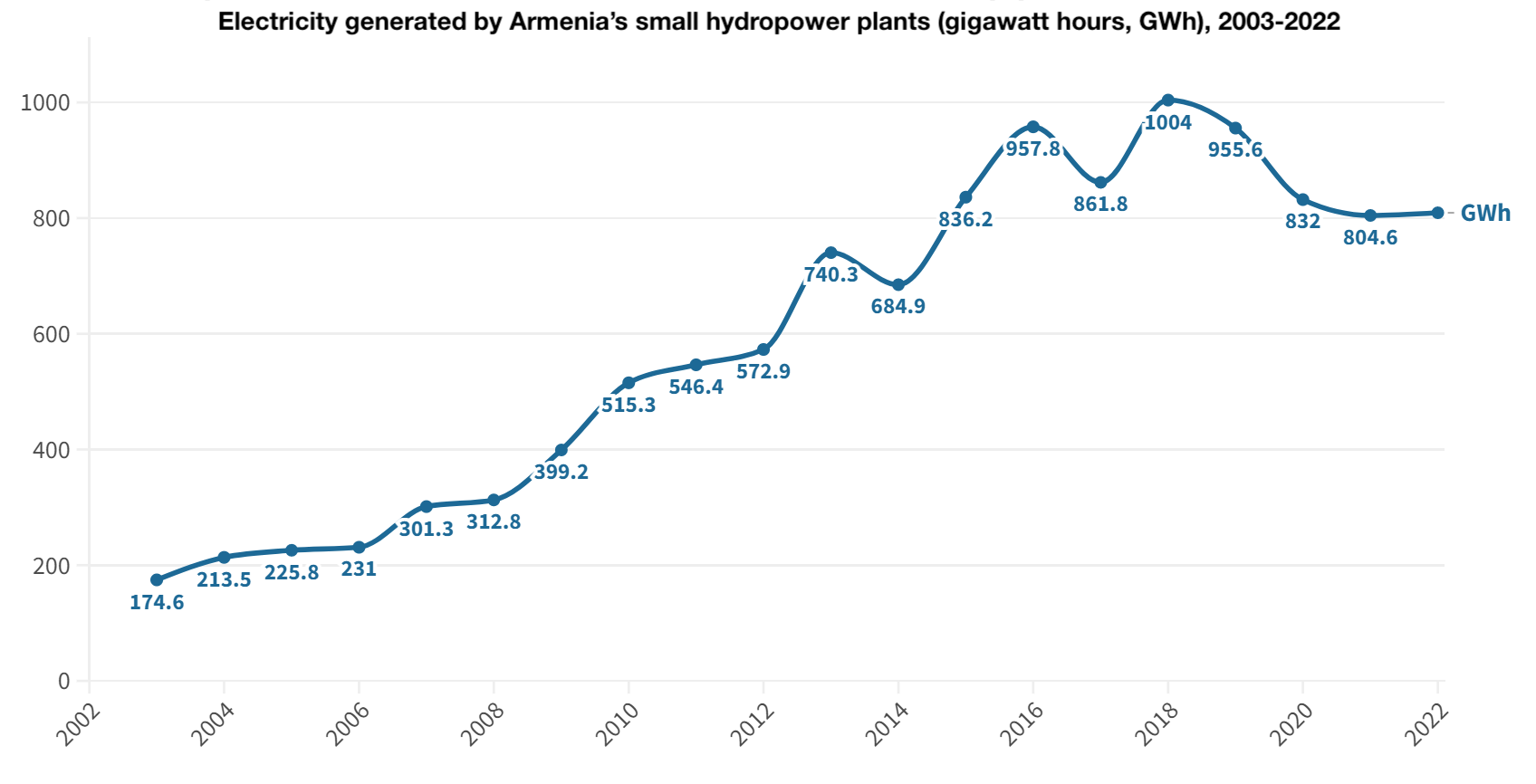

Hydropower is Armenia’s largest renewable electricity source. It is composed of two large cascades on the Hrazdan and Vorotan rivers and 188 small hydropower plants (HPPs) spread around the country. The small HPPs have an overall capacity of 389.3 MW and average annual electricity generation of 909 gigawatt hours (GWh). The Sevan-Hrazdan cascade, fed by Lake Sevan, consists of seven HPPs with a combined capacity of 561.4 MW and historically maximum annual generation of 2,500 GWh at the expense of lowering the levels of Lake Sevan, but the figure has stood at around 450 GWh in recent years. The Vorotan complex, located in Syunik region, consists of three HPPs with a combined capacity of 404.2 MW and annual generation of 1,150 GWh.

In the past two decades Armenia experienced a small HPP boom largely due to regulatory changes. In 2004, the government introduced fixed prices for electricity generated by small HPPs making it a predictable and profitable business for investors. More than 70% of the licenses were granted between 2006 and 2015.

Source: Public Services Regulatory Commission

The largest small HPP has 26.4 MW capacity and is located on the Dzoraget River in the northern region of Lori. There are further 14 small HPPs with capacity larger than 5 MW, but almost 40% of Armenia’s small HPPs are “mini” HPPs with a capacity less than 1 MW.

Almost half of Armenia’s small hydro capacity is located in the two southern regions of Syunik (27.2%) and Vayots Dzor (20.3%). They are followed by Lori (17.4%), Aragatsotn (8.7%), Gegharkunik (7.6%) and Tavush (6%).

Untapped Hydro

Most of Armenia’s hydropower potential is already tapped, but there remains some significant unrealized potential. In its long-term strategy, the Armenian government stated its goal to attract $100 million to tap the additional small hydro potential, increasing its overall capacity from 380 to 430 MW. The government further noted that while plans for three large hydropower plants (Meghri, Shnogh and Loriberd) have been left out of current plans due to high upfront costs, they remain important for Armenia. The government says they are of “systemic significance” and will be built “when the need for the construction of such capacities arises in the electric power system.”

The proposed Shnogh HPP, on the Debed River, has been calculated to have a potential capacity of 70 or 75 MW (and annual generation of 270 GWh), while the capacity of the proposed Loriberd HPP on the Dzoraget River, is set to be 66 MW (generation at 208 GWh). Both are located in northern Armenia. The proposed Meghri HPP, long a subject of consideration and discussion by Armenia and Iran on the Araks (Aras) River shared by both countries, is proposed to have a capacity of 130 MW and annual generation of 797 GWh.

Other Renewables

Armenia has other renewable energy sources. The geothermal energy potential of Armenia is significant, but is not considered economically viable, at least for now. The World Bank has estimated the total potential at around 150 MW. The Karkar site in Syunik, for instance, has an estimated capacity of 28 MW with a construction cost of nearly $100 million, far pricier than solar. The country has a single biomass power plant, opened in 2008, with a capacity of 0.8 MW and generation of 2.3 GWh. Located in Lusakert (Argel), it is powered by chicken manure produced at the Lusakert Poultry Farm.

Also see

Magazine Issue N28

Magazine Issue N21

Magazine Issue N9

Related

Environment and Energy Through the Public’s Eye

Improvements in low-carbon technologies, driven in part by foreign energy policy, have created new opportunities for Armenia, a country without fossil fuel reserves, aligning environmental concerns and the pursuit of higher energy security more than ever before.

Read more

Dear Hovhannes

Your article is very good and instructive, though, I have to say that the Wind Energy part is based on out of date data, the wind map generated in 2003 by USAID is not accurate and up to date.

Therefore the potential installed capacity is inaccurate and underestimated.

There are new tools such as the Global Wind Atlas (https://globalwindatlas.info/en/area/Armenia) that demonstrate well that the 2003 study is with nowadays tools and technology, underestimated.

I have made a presentation at UNDP Armenia in 2020, with full demonstration of it:

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1S-ut5rgPCImH–a7lnvNRuqu-8zQt-Le/view

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1cwpxqmtIg84K2XDNu44zVaOCFnPkhx-I/view

For instance, the USAID report claims that only 8% of the armenian territory has a mean wind power density of 300W/m² or more at 50m above the ground.

The Global Wind Atlas, claims that 10% of the armenian territory has 600W/m² or more (@ 50m above the ground). Whatever how you take it, even with high precaution, the data from 2003 USAID are out of date and underestimated.

If you need further explanations, feel free to contact me.

All the best, Régis DANIELIAN