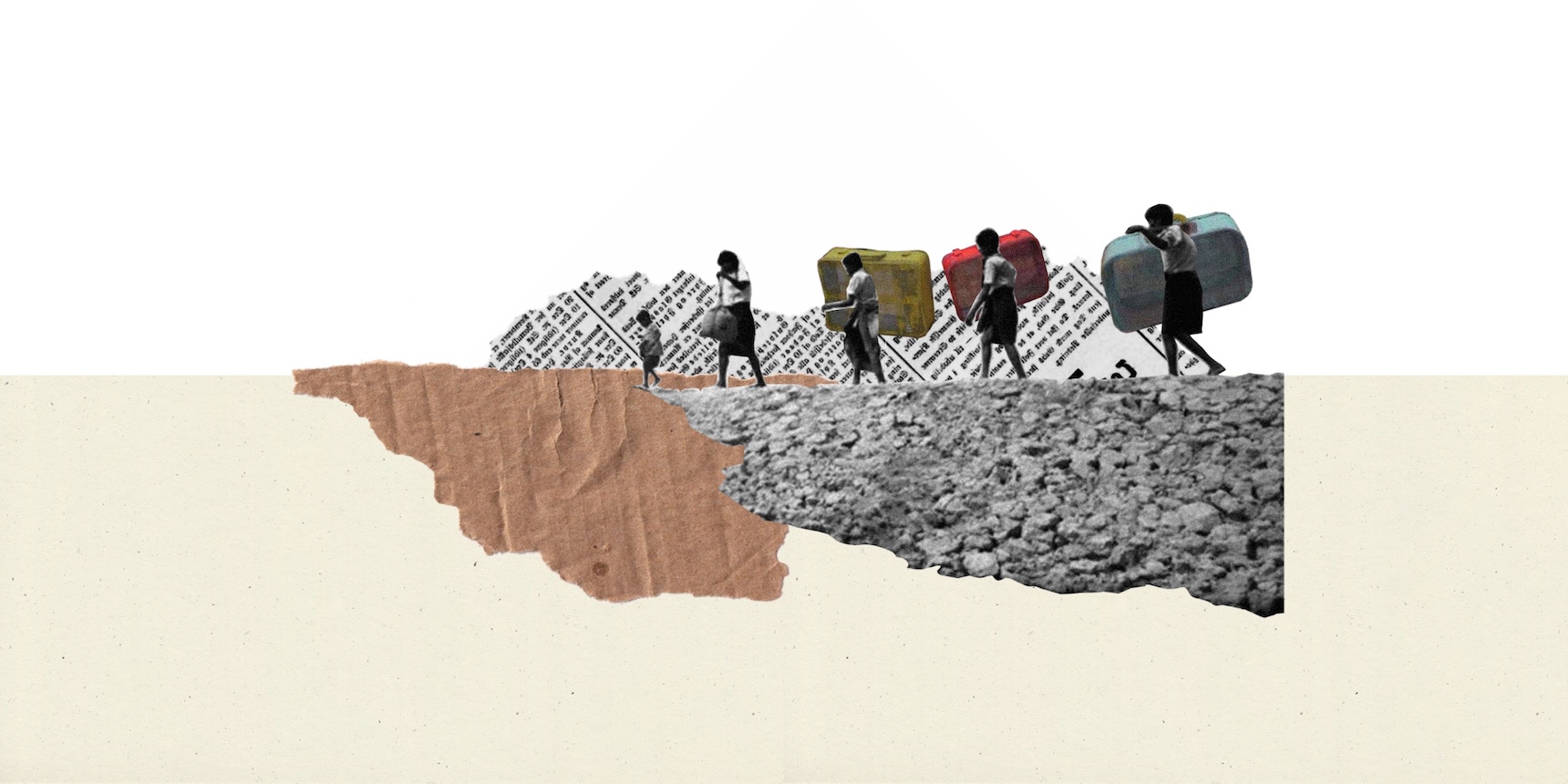

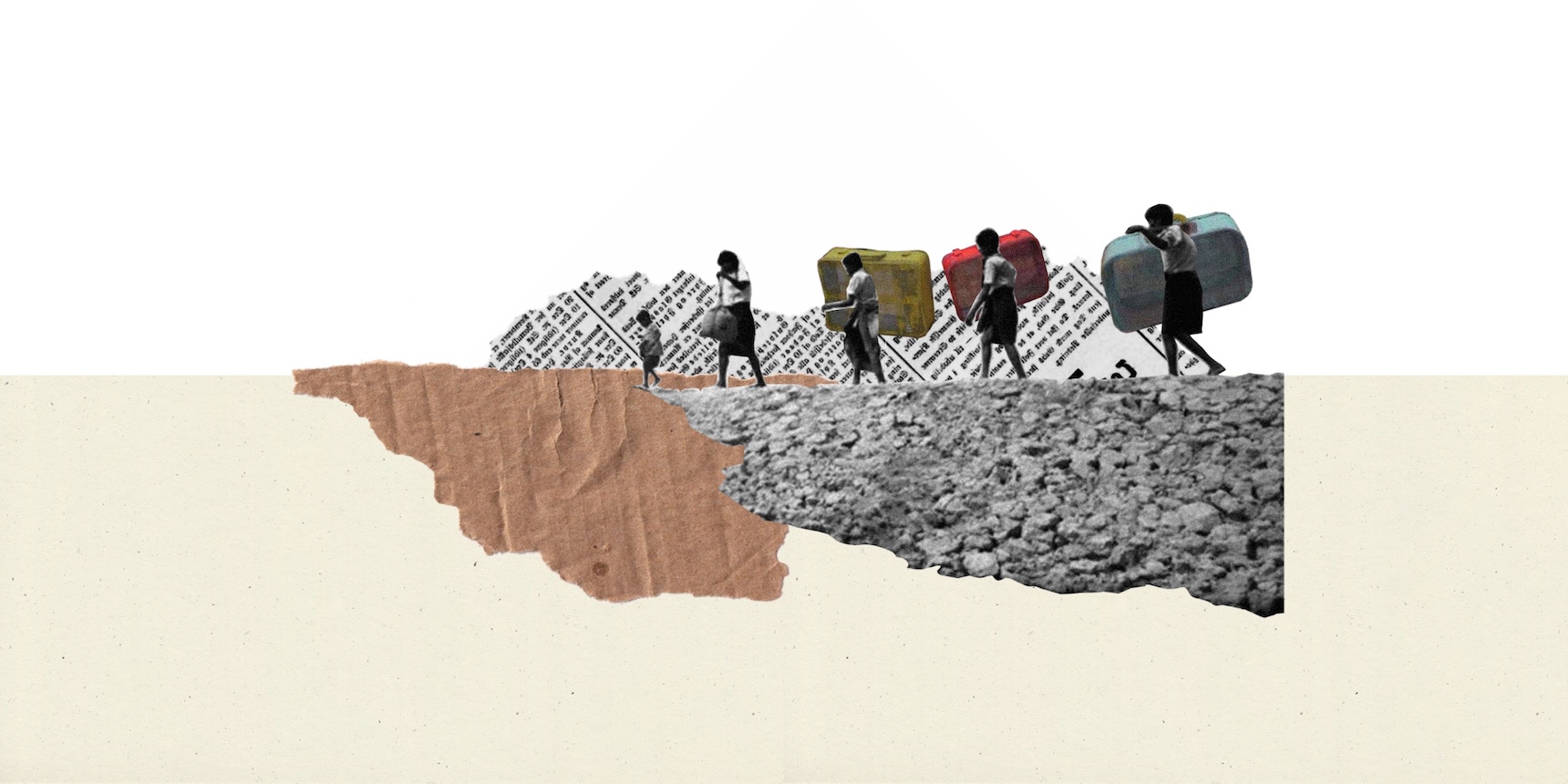

In a matter of days, after almost ten months of living in a blockade, constant threats, violations of the ceasefire and following a large-scale military attack by Azerbaijan on September 19, over 100,000 indigenous Armenians of Artsakh were forcibly displaced from their ancestral land.

“Analysis shows that, in the coming days, there will no longer be any Armenians left in Nagorno-Karabakh,” PM Nikol Pashinyan said during the September 28 government session. “This is ethnic cleansing in the most direct sense of the word and something that we have been alerting the international community about for a long time.” As of October 6, Artsakh has been left without Armenians.

Azerbaijan presents the forced deportation of the Armenians from their homes in Artsakh as an act of “free choice.”

Azerbaijani presidential advisor, Hikmet Hajiyev, in an interview to Deutsche Welle insists that Azerbaijan has not forced anyone to leave: “People are leaving by their own will. It is their personal decision. The anti-terrorist operation was not aimed at the civilian population or the infrastructure.”

International legal expert Ara Ghazaryan points out that it is not necessary for people to be driven to the border under violence and force for it to be considered forcible displacement. Conditions created in Artsakh had made it impossible for people to continue to have dignified lives on their land.

“Even Azerbaijani propaganda cannot negate the fact that if 100,000 people leave a given area in the space of a couple of days, then it can not be free will,” says Ghazaryan.

Anna Melikyan, a legal specialist with the Protection of Rights Without Borders NGO, said what took place in Artsakh can be precisely qualified as forced displacement, because the conditions that were created for the indigenous population leave no room for a feeling of safety, forcing people to leave their homes.

“One of the end results of the military operations was to leave Artsakh without Armenians – ethnic cleansing,” Melikyan explained. “It would appear that the population is leaving on its own accord, in their own vehicles, but these are indicators that people are leaving their homes fearing for their life, health and other rights.”

Melikyan pointed out that signs of a creeping ethnic cleansing process had become evident as early as 2020. Although it wasn’t executed through active military operations, the circumstances created a situation that compelled people to leave.

“After enduring ten months of a blockade with limited access to food, electricity, and gas, the situation became conducive for people to leave as soon as the road opened. However, this alone did not appear to be enough. Perhaps they weren’t entirely confident they could reach their goal, so they initiated military action,” says Melikyan referencing Azerbaijani President Aliyev’s remarks following the closure of the Lachin Corridor who said, “The road is open for those who do not wish to become Azerbaijani citizens.”

Taking all of this into consideration, we can certainly call this a ethnic cleansing,” Melikyan explains.

Ethnic Cleansing Without Documentation

There are concerns about a lack of documentation and gathering of evidence by international organizations, humanitarian missions and international journalists about the ethnic cleansing. She says as opposed to the 2020 Artsakh War, when there was the possibility to go to Artsakh, organize fact finding missions and register violations, the situation now is more complicated and these must be addressed from the territory of Armenia. There was a large number of international press in Kornidzor and Goris to witness the flow of the people, Melikyan explains and adds that the testimonies need to come from the people themselves. They need to provide testimonies about the shelling, what was targeted and destroyed and if civilian infrastructure was targeted

Melikyan also points out that during the 2020 war, the Azerbaijani side often shared videos to social media that served as evidence of war crimes. This time however, authorities in Azerbaijan shut down even Tiktok and videos on social media were very limited, which according to Melikyan was done to preempt the dissemination of videos by Azerbaijani soldiers that would serve as evidence of war crimes.

“They want to convince the world of the contrary,” she says. “They are posting propaganda videos of them treating the wounded Artsakh Armenians, making a point of showing that they are helping the civilian population and are ready to guarantee their safety.”

Legal Action

Taking into consideration previous experiences, it is important to have the deeds to the properties left behind. These will be required when building cases in international courts.

“When you file for compensation, you need to present what has been lost and what needs to be compensated for,” Melikyan says. “Unfortunately, we are all aware that, in case of forced displacement, people do not have the means to bring with them all that would be necessary. However, everything from photographs to videos and other documents can be of value.”

Ara Ghazaryan says that even when the region has entirely passed under the control of Azerbaijani jurisdiction, and even if Azerbaijan nationalizes private and even public property, this still does not mean that people lose their rights to the property.

“The legal evaluation of what Azerbaijan has done will be given taken into consideration the entire context, stating with the military operations, to their proportionality, to Azerbaijan’s general policy towards ethnic Armenians,” says Gazaryan, adding that, in legal terms, there is still much to be done in the future, both qualitatively and quantitatively, many legal processes are ahead, which are in favor of the Armenian side. “When you see a video of an Azerbaijani opening fire in the direction of a church, with no military post in the vicinity and no possibility of claiming an advantageous military position, it becomes clear that there has been an order to destroy, and this is with the aim of ethnic cleansing. Cultural centers, anything with cultural significance is being targeted, this is so that people would not wish to or be able to continue inhabiting the region.

Ghazaryan points out that ethnic cleansing is as much a war crime as it is a crime against humanity for which responsibility lies with the government, as a subject of international law, as well as on the individual, soldiers, and their commanders.

“Who would, on their own free will, leave behind their home, their property… the reasons in this case are many, from Aliyev’s statements to the latest military operations targeting civilians, their residences, cars. Azerbaijan will have little to no counter arguments to these facts and will subsequently try to address the situation on a political platform, because that is where it has the advantage,” Ghazaryan explains.

Meanwhile, Azerbaijan has already arrested high-ranking Artsakh officials. There is the recurring news of an Azerbaijani “black list” with more than 300 names on it against whom criminal cases have been initiated. The first arrest of the “list” was on September 27 when former State Minister of Artsakh, businessman, philanthropist Ruben Vardanyan was arrested at the Hakari checkpoint on the Lachin Corridor.

An Azerbaijani court sentenced Vardanyan to four months pretrial detention. He has been charged with financial terrorism, formation and participation in the activities of illegal armed groups, and illegal violation of the state border.

Former Foreign Minister of Artsakh, Davit Babayan was also apprehended and charged by Azerbaijan for planning, preparing, launching and conducting war, recruiting mercenaries, violating the norms of international humanitarian law during an armed conflict, organizing terrorism, inciting inter-ethnic enmity.

Baku also holds Levon Mnatsakanyan, the former commander of the Artsakh Defense Army, and former deputy commander Davit Manukyan, as well as the former presidents of Artsakh, Arkady Ghukasyan, Bako Sahakyan, Arayik Harutyunyan, and speaker of the National Assembly, Davit Ishkhanyan.

According to Ara Ghazaryan, Azerbaijan will directly take these cases to criminal court in an attempt to demonstrate that these are legal and legitimate processes. But he notes that Azerbaijan will also need to respect the rights of the people it has detained, starting from the procedural requirement of conducting the first interrogation to giving them the opportunity to have legal representation of their own choosing, which Ghazaryan says is not something he expects Azerbaijan to abide by. “In the last 21 years, that has never been the case. As a rule, they appoint the attorney and it is not possible to get in contact with this attorney, even the wife of the ‘accused’ is not given a chance to speak with his attorney,” Ghazaryan says.

More importantly, Ghazaryan points out that Azerbaijan tends to give terrorism a pretty wide and open definition, and as such, it is important to pay attention to what the charges brought up against former officials are. “According to them armed resistance is terrorism, which is not what criminal law describes it as,” he says. “Any objective or subjective definition of terrorism by Azerbaijan is skewed. In actuality, this is political persecution imitating legitimate legal procedures.” Vardanyan’s case will be more complicated for Azerbaijan, because he is a well known political figure with international connections, Ghazaryan explains.

Refugees?

The Armenian population of Artsakh have Armenian passports and are considered citizens of the Republic of Armenia, which makes the issue of their legal status more complicated. The law on “Refugees and asylum seekers” of the Republic of Armenia, which is based on the 1951 UN Refugee Convention and the 1967 protocol on the Status of Refugees, both of which Armenia became a signatory to in 1993, give an array of possibilities for refugees and guarantee their rights. But the process of establishing a refugee status assumes the involvement of two different countries, therefore, the people of Artsakh cannot be refugees in Armenia.

Ara Ghazaryan, however, points out that a population has left its place of permanent residence because of fear, which obliges any country, per international norms, to accept them if they ask to be let in. “Although theoretically, from the point of view of international law, they do not correspond to the term refugee but the fact is that they are in a refugee-like situation and have the same need for support that refugees in the classical sense have.”

Recently published

Research and Innovation in Armenia: Are We On the Right Path?

Successive administrations in Armenia did not adequately invest in science and education, hindering the development of human capital and infrastructure. To register comprehensive progress, ensure sovereignty and security, a robust R&D ecosystem must be revived with the government playing an indispensable role.

Read moreThe EUMA After the Fall of Artsakh

With the collapse of Artsakh, will the EU further enable Baku’s irredentist agenda to seize Armenian territory as part of the opening of the “Zangezur Corridor” or will Brussels show the same initiative to sanction and deter Azerbaijan that it deployed in response to Russia’s aggression in Ukraine?

Read moreCan the International Community Reverse the Ethnic Cleansing of Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh? Part 1

The collapse of Artsakh is the failure of preventive diplomacy, the end of the human-rights-based liberal world governance system and can embolden other autocratic states to use force against small entities claiming self-determination to subjugate or eliminate them in other parts of the world.

Read moreFrom Constructivist to Liberal Realism: From Nation to State

The restoration of Armenian sovereignty in 1991 prompts us to contemplate the future of Armenia and its position in the international order, writes Gaidz Minassian.This is all the more pressing when the Armenian state has never been thoroughly examined through the lens of international relations theories.

Read moreWhat Happened to the Promise of Leaving No One Behind?

Despite unequivocal evidence, the United Nations, like other international actors, failed to address the threats looming over the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh, who today are uprooted, homeless, forcibly displaced with thousands more still fleeing.

Read more

Armenia should develop a long term strategy for dealing with the Artsakh refugees. If economically possible, they should try to keep most of them in the same geographic area near Goris so that they can recreate a life similar to what they had, a combination of rural farms, villages, small towns and some city inhabitants. They should not be dispersed all over Armenia nor to emigrate. The cohesiveness is important for their well being and also for a future return to Artsakh. Never say never!