“My son was going to leave us. I was going to lose him. But even in this situation, palliative care helped me get through it,” recalls Irina Grigoryan. Her son, Armen Khachatryan, 12, passed away in October 2021 after battling cancer for almost two years. Irina spent the final week of her son’s life in the newly opened Palliative Care Center at the Ruben Yeolyan Hematology Center––the first children’s palliative care center in Armenia.

“You realize that you are going to the very end with your child; that there is no alternative; and that all medical interventions have been exhausted. At the same time, a thousand and one problems arise, but the medical staff is standing beside you, ready to lend you a hand,” says Grigoryan.

Armen Khachatryan was transferred to the Center after being given the strongest medication possible for pain relief. “It is the stage where you feel your child is slipping away. The world was no longer interesting to him; the pain was unmanageable. He felt nothing. Some people in that situation might want to be with their family; we preferred the Center where we could enjoy the last days of Armen’s life. It was a different, spiritual tranquility that I found there during that time,” Grigoryan recalls.

Every moment of the week spent in the Palliative Care Center is etched in the woman’s memory. She says that although the suffering in this case is very personal, the medical team was very kind and compassionate.

“I felt as though the doctors and nurses were trying to support me and Armen not as professionals, but as people. A few days before Armen passed, I wanted to bathe him. It was difficult to move him; he was heavy, but everybody helped and together we bathed him. This was very important for me. Even though the doctor explained to me several times that it was pointless, that we were torturing the child; but on the other hand, she also understood me, the need for my conscience to be clear that my son should feel that he was important and loved,” recalls Grigoryan.

Pediatric Palliative Care in Armenia

According to the World Health Organization, palliative care is a crucial part of integrated, people-centered health services. Palliative care is an approach that helps improve the quality of life of patients and their families facing issues around terminal illness. It prevents or relieves suffering through pain treatment and management, and provides the patient and their loved ones with psychosocial and spiritual support.

An individual approach is required for adults and children. Palliative care is typically given to adults with oncological diseases and other terminal illnesses. Children may require palliative care as early as infancy in cases of congenital defects and other genetic diseases.

Palliative care for children is prescribed for four different categories of pediatric disease: those with life-threatening chronic diseases for which there is no effective treatment; those with conditions where the risk of premature death is high, and long-term, intensive treatment is necessary; those with progressive disorders for whom palliative care is necessary from the time of diagnosis; and those with non-progressive, severe, irreversible conditions, which rehabilitation treatment will not alleviate.

The Palliative Care Center opened its doors in September 2021. The clinic has five beds and is intended for children with onco-hematological diseases. There are another three beds in the Arabkir Medical Center, designated for serious and life-threatening cases.

“Whether we were at home or in the hospital, my son was going to depart; I was going to lose him, but palliative care helped me. Even after his passing, I am still in contact with the doctors and our psychologist there,” says Grigoryan, months after losing her son.

Managing Symptoms

Anoush Sargsyan, director of the Palliative Care Center, says that their main goal is to relieve pain, yet children frequently find it difficult to describe their level of suffering.

“We have children who, along with the disease, have various mental issues and cannot explain the extent of the pain or where it hurts. We evaluate whether the child is in pain or not by other indicators,” says the specialist, noting that there are other symptoms they must attend to: lack of appetite from medication, nausea, vomiting, and constipation. “All these symptoms must be managed. We have children who have mobility issues and develop bed sores after spending a lot of time lying down. We have special mattresses for these cases.”

According to Sargsyan, although adults can often battle oncological disease and undergo chemotherapy for years, the same diseases can develop more rapidly in children.

“In children, both the beginning and the end can be very aggressive. We cannot artificially prolong life, but if a child’s severe pain is prevented, then it is already a change in the quality of their life,” explains the specialist.

The Need for Outpatient Services

Irina Grigoryan, who used inpatient palliative care, says it is also necessary to think about developing an outpatient palliative care service, as many prefer not to go to the hospital.

Although Armenia now has a total of eight beds for inpatient children’s palliative services at the Palliative Care Center and the Arabkir Medical Center, the Ministry of Health says that over 3000 children need palliative care – the majority of whom require it outside of a hospital. As a result, the Ministry intends to increase the availability of outpatient pediatric palliative care services.

Head of the pediatric unit of the Ministry of Health’s Department of Maternal and Child Health, Lilit Avetisyan says that they are currently developing standards for inpatient and outpatient palliative care for children. They are studying best international practice in order to understand how to adapt a model for the Armenian context.

“Specialists will be trained in order to identify and guide children correctly and in time. Discussions are underway to determine which cases and diagnoses require outpatient treatment. No child in need of care should be left behind,” says Avetisyan, adding that the focus of palliative care is not just the child, but also the family, which should be part of the care.

Palliative care, according to Avetisyan, encompasses more than just diaper changing and bathing patients.“There are various medical interventions that the parent cannot do alone, for example, administering a probe, cleaning an ulcerated surface, and maintaining basic hygiene,” she says. “Of course, the parent learns in the process.”

The five beds in the Children’s Palliative Care Center are intended only for children with oncological diseases, and not all the beds are always fully occupied. The department has admitted ten patients over the past year.

“The nature of the disease is such that children can die early. This means beds become available. But we cannot accept other children whose life expectancy is longer, despite their need for palliative care,” says Anush Sargsyan, explaining that if they accept children with various neurological problems who need palliative care, the beds will become occupied, leaving no room for cancer patients.

This center currently does not offer outpatient services, but according to Sargsyan, they have developed a package of proposals together with the Arabkir Medical Center, presented it to the Ministry of Health, and are getting ready to launch a pilot program in order to better understand future developments.

Children’s palliative care typically employs physicians, nurses, psychologists, and social workers. Inpatient palliative care is more expensive than outpatient palliative care, which is why efforts are being made to implement the out-of-hospital service, where the parent will care for their child on their own, and will not require an orderly or a nurse.

According to Sargsyan, the state provides only 10,000 AMD per day per child for inpatient palliative care––an insufficient amount. “The wages of the orderlies alone is more than 10,000 AMD a day, and if we have four or five children in the department, we can hardly make ends meet,” says Sargsyan. She adds that the department’s primary funding comes from savings from other services, and that they have requested an allocation of at least 30,000 AMD per day from the state

Helping Adults

Head of palliative therapy at the V.A. Fanarjyan National Center of Oncology, Dr. Hrant Karapetyan has been working since 2000 to introduce palliative medical care in Armenia.

“It took 22 years before this idea became a reality in our country. Ten palliative care beds [for adults] have been available in this hospital since 2011. At first, it was a paid service, but we fought for state funding [for vulnerable groups] because the public couldn’t afford it,” says Karapetyan. He notes that with those ten beds they served 119 patients in 2020, 346 patients in 2021, and 229 patients so far in 2022.

Pain Relief

According to Karapetyan, the most crucial aspect of their work is providing patients with adequate pain relief treatment.

“Many patients come with severe pain. Appropriate medication can help alleviate the pain,” explains the doctor, emphasizing that the essence of palliative care is neither to prolong nor to shorten life. He explains that their priority is to improve the quality of life of patients as much as possible.

Karapetyan complains about Armenia’s polyclinics, where doctors frequently fail to provide patients their prescribed medication.

“While they are in the hospital, we provide them with the necessary medication, and when they are discharged, we give them their medical case history, which confirms that the patient has been discharged and is prescribed with the necessary pain relief medication. However, when discharged patients take their medical file to a polyclinic, they encounter problems [medical staff at polyclinics are wary of the strong pain relief medication]. Meanwhile, all doctors who deal with pain management have the right by law to prescribe these pain relievers,” explains Karapetyan.

According to the doctor, in order to determine what kind of palliative care Armenia needs and how it should operate, research was conducted in 2010 with the help of the Worldwide Hospice Palliative Care Alliance. That study found that 3200–3600 Armenians require palliative care.

Not Business, But Humanity

The National Oncology Center’s new palliative care unit, which will provide 30 beds and all necessary amenities, will open its doors in the fall of 2022. Patients will be cared for by trained medical staff. Patients’ rooms will have two entrances: one facing a garden which will be used by the patient to meet with visitors and for breaks, and the other for medical personnel.

Narek Manukyan, director of the National Oncology Center, reports that discussions are currently underway to determine whether the treatment will be free or covered by the state, as well as how many rooms will be reserved for those eligible for state subsidies. But Manukyan is confident that all their efforts will mean that it will be accessible to everyone. “This is not a business project; it is a humanitarian endeavor funded by the medical facility. This does not imply that the facility’s primary objective is to generate revenue. Everyone wants it to be free and accessible to people, just like nursing homes. Just as no elderly person should be left on the street, no one in need of palliative care should be denied it,” he says, adding that soon an outpatient palliative service will also be operational. This service will be available on call. Although the program is new and ambitious, Manukyan hopes that within a few months it will mature into an efficient service.

Hrant Karapetyan, head of palliative therapy at the National Center of Oncology, says that although their work is challenging, they are now able to reduce patients’ suffering by 80%. The specialist equates palliative care with the Armenian saying tsaved tanem [let me take your pain].

“We are able to manage everything that impacts the patient’s life, including physical and mental suffering,” says Karapetyan.

Also see

Palliative Care: The Right to Life with Dignity

Palliative care is an approach that strives to improve the quality of life of patients who are terminally ill; it endeavors to provide a life of dignity. In Armenia, culture, stereotypes and entrenched practices make this approach very difficult to achieve, and instead of helping the patient, often causes them to lose their voice and their dignity.

Read moreIll and in Anticipation of a Miracle in Germany, Part 1

Refugees have been living in a Düsseldorf's shelter for years, receiving treatment and waiting to either fully recover or be deported. In this series of articles, Armenians reveal how they arrived in Germany in anticipation of a miracle.

Read moreIll and in Anticipation of a Miracle in Germany, Part 2

Armenians, desperate for life-saving medical treatment, travel to Germany with hopes and great expectations. However, sometimes, those hopes remain unfulfilled.

Read moreUnderstanding Postpartum Depression

Having a baby is the most joyous time in a woman’s life. The experience triggers powerful emotions and in some cases, can lead to postpartum depression. Gohar Abrahamyan provides valuable insights through her own personal journey.

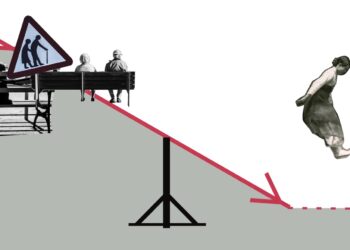

Read moreArmenia in Demographic Crisis

Recent data warns of a demographic crisis in Armenia. In a country with a high rate of aging, programs are being implemented to boost birth rates. But are they effective?

Read moreCatching Cancer in Time

The case for early detection of cancer and shifting cultural attitudes toward seeking medical treatment in Armenia.

Read moreObstetric Violence: Hidden in Silence

Many women are subjected to obstetric violence, which not only violates their right to receive dignified and respectful health care but can also seriously threaten their life and health.

Read more