Armenia! the groundbreaking exhibition that opened in New York City at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Byzantine galleries on September 22 asserts the full force and importance of Armenian cultural, religious and commercial contributions over a span of more than 14 centuries.

Curator Helen Evans begins her remarkable overview in the fourth century when Armenians converted to Christianity and developed their own unique alphabet, up until the 17th century when they controlled global trade routes from South East Asia all the way East through the Balkans into Western Europe. Evans is the Mary and Michael Jaharis Curator for Byzantine Art at the Met and specializes in Armenian art, having received her PhD from New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts with a thesis on “Manuscript Illumination at the Armenian Patriarchate in Hromkla and the West.” She has lectured and published widely on cross-cultural currents in the development of Christian art, style and iconography and co-curated another blockbuster exhibition at the Met, “The Glory of Byzantium” in 1997 as well as “Treasures In Heaven: Armenian Illuminated Manuscripts From American Collections” at the Pierpont Morgan Library and the Walters Art Gallery in Baltimore in 1994.

The current exhibition is a pet project of sorts for the curator, who has called it “a culmination of a lifelong dream” to bring together medieval Armenian treasures from all over the world. Putting together the exhibition was no easy task. Funding came mainly from the Hagop Kevorkian Fund and a select few Armenian foundations such as the AGBU and The Hirair and Anna Hovnanian Foundation. Evans reached out to non-Armenian funding sources as well, including the Carnegie Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts. But while the majority of the funding came from diasporan sources, the effort as a whole was truly pan-Armenian. Objects are on loan from the Republic of Armenia’s Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin and the Matenadaran, as well as well as the History Museum of Armenia. The four corners of the Armenian Diaspora were tapped for sources as well, including the Calouste Gulbenkian Museum in Portugal which lent several items, along with The Holy See of Cilicia in Lebanon, the Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem, and the Armenian Mekhitarist Congregation in Venice. In the United States major contributions were made by the Diocese of the Armenian Church in New York, the Armenian Museum of America outside of Boston and the Alex and Marie Manoogian Museum in Southfield, Michigan. Additional works come from The Met and other American and European institutions. In several interviews, Evans has emphasized the amount of persuasion and negotiation that is required for institutions in far-off countries to lend out such treasures, even when the host museum is as prestigious and respected as the Metropolitan.

As the text to the exhibition notes, over the centuries Armenian merchants and clergy brought back to the Armenian homeland—an area that historically stretched from the Caucasus and the plain of Mount Ararat down past Lake Van into Cilicia and Anatolia, depending on the century—books printed in Armenian printing presses as far away as Amsterdam and India, as well as spices, textiles and other precious goods. It was during these Medieval centuries that Armenia—independent for only about a century in Cilicia—nevertheless sat at the crossroads of at least four powerful Empires: Greek Byzantium, Safavid Iran, Ottoman Turkey and Imperial Russia. Each one influenced the Armenians and the Armenians in turn influenced both neighbors and invaders.

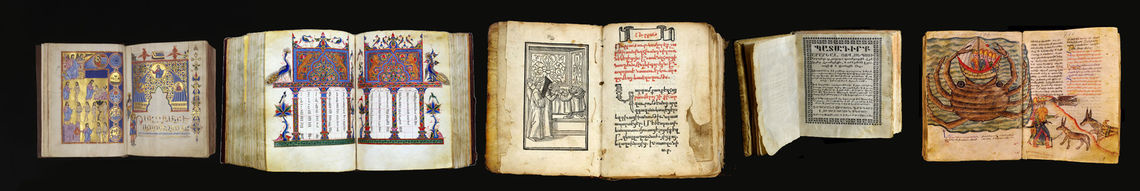

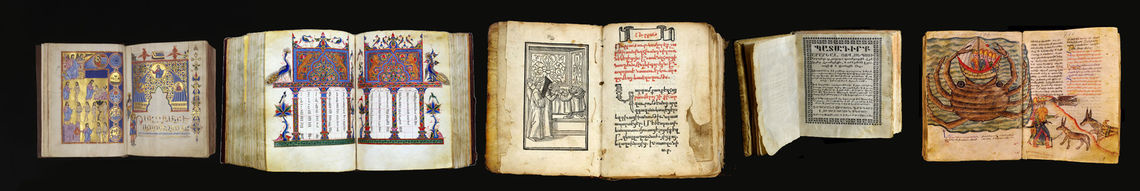

At monasteries such as Dvin, Sis and Hromkla, vast scriptoria produced sumptuous illuminated manuscripts reminiscent of their Russian and Greek Orthodox counterparts but in a style and colors uniquely their own. Starting as early as the 14th century in Ottoman cities such as Kütahya and Iznik, Armenians craftsmen were in the vanguard and played a decisive role in the development of these two renowned schools of ceramics and tile making. In the Kütahya school of ceramics in particular, the presence of dragon motifs and others typical of Sino-aesthetics are indicative of the the fact that Armenians controlled trade routes all the way to China—the 18th Century Hexagonal Tile with Architectural Scene on loan here from the Manoogian Museum provides a strong example of Kütahya design.

Elsewhere in the exhibition, fascinating maps that depict far-flung trade routes and one that serves as a kind of yellow pages of Armenian churches around the world hint at the breadth of Armenian culture. The singularity of this particular show is to place the Armenian achievement within a global context. Incredibly enough, much of this art was created as Armenia suffered wave after wave of invasion—be it Byzantine, Arab, Persian, Mongol or Turkic. In the process the Armenians learned to create and thrive in the most adverse of circumstances. The exhibition itself is divided into five main galleries, each one dealing with a different era or subdivision of Armenian art. The first gallery recounts the historical conversion to Christianity in 341 and existing trade at the time, while another is devoted specifically to Armenian architecture and yet another to the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia that bordered the Mediterranean around Adana and Adiyaman—today’s Cukurova province in Turkey. Armenian liturgical objects fill another gallery, while the remaining two are devoted Armenian trade routes in the Ottoman and Safavid Persian empires.

Armenian scriptoria at Gladzor and Dvin produced some of the finest examples of illustrated manuscripts to be found anywhere. Colophons identify the scribe and illuminator but also depict the patrons who included themselves in the illustrations—something unique to the Armenian tradition. Though this may appear somewhat self-aggrandizing, in retrospect it has been a godsend, as it has helped generations of manuscripts to be properly identified and categorized, and has contributed to piecing together other aspects of medieval Armenian history. Two gospel books from 1256 Hromkla made of tempera, ink, and gold on parchment are particularly noteworthy as are other works by Toros Roslin, perhaps the most famous painter of illuminated manuscripts in the Armenian tradition. There’s also a rare and particularly exquisite 6th century silver hanging Censer with Six Holy Figures from Constantinople on display.