Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

In October, I took part in two exhibitions, both of which dealt with the problem of waste, and the interaction between waste and art.

It may not be ethical to write a critical review of exhibitions in which you have been directly involved, but this review is also an attempt to talk about these events critically and look at them from an insider’s point of view.

Most of the exhibitions organized in Armenia in the post-war period refer either to the war or to related topics such as issues of historical memory or heritage. But it is interesting to note that two recently-opened shows depart from this context, referring to a more broadly “warlike” situation—the issue of waste. Among obvious reasons (for example, funding for exhibitions on specific fields or specific topics), we should consider other likely motives for choosing the topic under discussion.

The state of self-isolation engendered by the COVID-19 pandemic forced us to look inside ourselves and contemplate to what extent humans themselves are guilty and responsible for what has happened, for global problems in general, and what they can change. These thoughts became even more poignant in Armenia after the war, when the “we are all guilty” thesis began to circulate widely.

Perhaps it is this approach to issues and problems that become exacerbated in emergencies, which leads to the need to talk about waste. This is the very point where the issue of human responsibility comes to the fore and opens a field for understanding the problem and seeking solutions, “starting with ourselves”.

“Turn Plastic Waste into Art”: this was the title of the exhibition organized on October 2-3, 2021 at the Latitude Art Space in the northern suburb of Yerevan, featuring four installations and one film. The installations were created by groups of artists. The organizer of the event was the Fashion and Design Chamber of Armenia NGO, whose mission, as stated on the association’s website, is to support the Armenian fashion industry and create a joint platform for the creative industry. This is important in order to understand the context, content and the trends followed by the exhibition.

Since the main professional direction of the organizers is fashion, this was very explicitly reflected in the exhibition. The exhibits were typified by their symmetrical forms, design solutions, the presence of clothing, attractive colors, etc. There was almost no variety of media here (if we ignore the fact that the waste itself contains a variety of materials), such as music, sound, lights, video elements, smoke, smell, etc. One of the five works presented was a video, but it was shown separately, not as an element of another exhibit.

This narrow focus is not a coincidence, especially if we look at the exhibition’s call for participation. Of course, there were no restrictions for participation, but there were preferred emphases: “The project aims to unite Armenian creatives to work together in making art objects and collections for raising awareness on the key issue of environmental pollution and plastic waste.” In a similar manner, the list of participants in the selection of groups also hints at the trends of the exhibition: fashion and graphic designers, illustrators, photographers, stylists, etc.

The name of the exhibition, “Turn Plastic Waste Into Art”, indicates that the overall intention is to use plastic to produce new works of art; in other words, recycling and obtaining a specific product. This intention is also clearly expressed in the exhibition’s press release: “raising public awareness about the issue of plastic waste by making art objects/collections.”

The term “environmental issue” is used a lot, both at the registration stage for participation in the exhibition and in its official announcements. This indicates that the presented installations would not only be works of art from recycled waste, but would also speak on environmental issues themselves. And since there is an “issue”, presumably they would also offer a solution, something we will not see in the case of the other exhibition also discussed in this article.

It can be said that the “issue-solution” formula is the primary basis of this exhibition. Moreover, the artist (or the artist collective) is the one who puts forward both the issues and the suggested solutions. This is the reason why the exhibits often leave no room for dialogue; they offer predetermined formulas. It seems that the artist has already decided what or who is the cause of the waste, what the solution is, and how to deal with the waste and the main “culprits” behind it.

For example, at the center of the performance-installation entitled “Reflection” (authors: Tatevik Harutyunyan, Metaks Karapetyan, Lusine Simonyan, Lilit Karapetyan), among other recycled elements, there is a chair with “sit” written on it. On the clothes displayed around it, is the following inscription: “The most dangerous animal on the planet.” In other words, here the human is presented as the most dangerous creature in the world. The group of artists has “found” the culprits, which is also emphasized in the informational video about the installation. “We have tried to depict plastic as ice, which has damaged nature, and man is responsible for this problem,” says one of the authors of the installation, and then offers a ready-made solution: “To solve this problem, we need to recycle, rethink and give new life to plastic.”

The group of artists behind the installation entitled “Goldfish” (authors: Sona Hovsepyan, Elen Hovhannisyan, Karine Martirosyan, Mariam Melikbekyan) has not only found the culprits, but also has a “verdict” for them. The “hook” of the installation is the goldfish made from waste, whose stomach is also full of waste. Next to it are containers with different samples of trash, with the fish’s curses toward man written on them. These thoughts are cutting and incisive: “May your coffee be made with this water, may Sevan be as black as this, may islands emerge from this, may your lungs be as clean as this, may your life be as colorful as this, may your children inherit this.” Such didactic finger-pointing comes across as more like a reprimand and hinders the possibility of a constructive dialogue between the work of art and the viewer.

The man-as-culprit theme reappears in the text featured in the video piece “How Plastic Ate Man” (author Mariam Energetic), and becomes the object of its reproach․ “Nature is suffering. We suffer because of ourselves. We throw trash to eat trash; we eat to throw trash. A miracle. We continue to live. Still. You don’t even notice how you eat plastic and won’t even notice how plastic ate you. Just don’t suddenly die because of yourself. THE BRAIN IS FOR THINKING DEAR HUMAN.”

“Reflection” installation, Tatevik Harutyunyan, Metaks Karapetyan, Lusine Simonyan, Lilit Karapetyan. Photo by FDC Armenia.

“Golden Fish” installation by Sona Hovsepyan, Elen Hovhannisyan, Karine Martirosyan, Mariam Melikbekyan. Photo by FDC Armenia.

Observing the exhibits, it is clear that they do not stand out in terms of originality of ideas, but follow globally-accepted trends and broad approaches on environmental issues. This is apparent, first of all, from the chosen topics themselves. Almost all of the works address global, universal ecological issues and not local, Armenia-specific issues. Even if these issues are localized, such as, for example, the weather map of Armenia made of plastic (“Climate from Plastic” installation; authors Sona Khachatrayn, Lia Petrosyan) or the “Goldfish” installation that touches on the water pollution of Lake Sevan, these are just concepts that have for the most part been thought and conceived not in this area or for this area, but simply been adapted and localized.

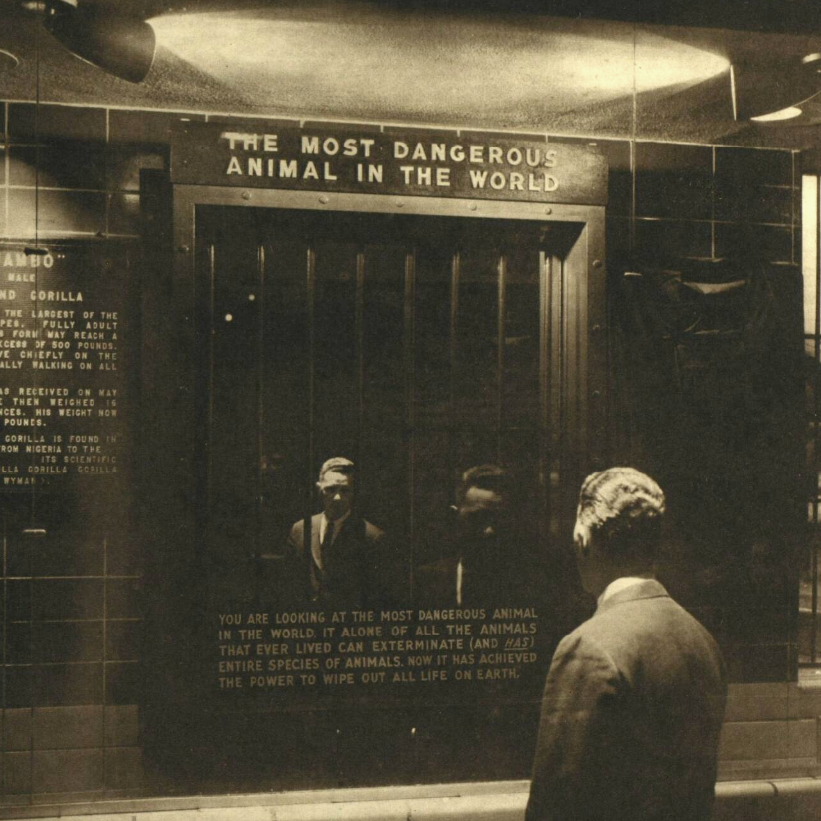

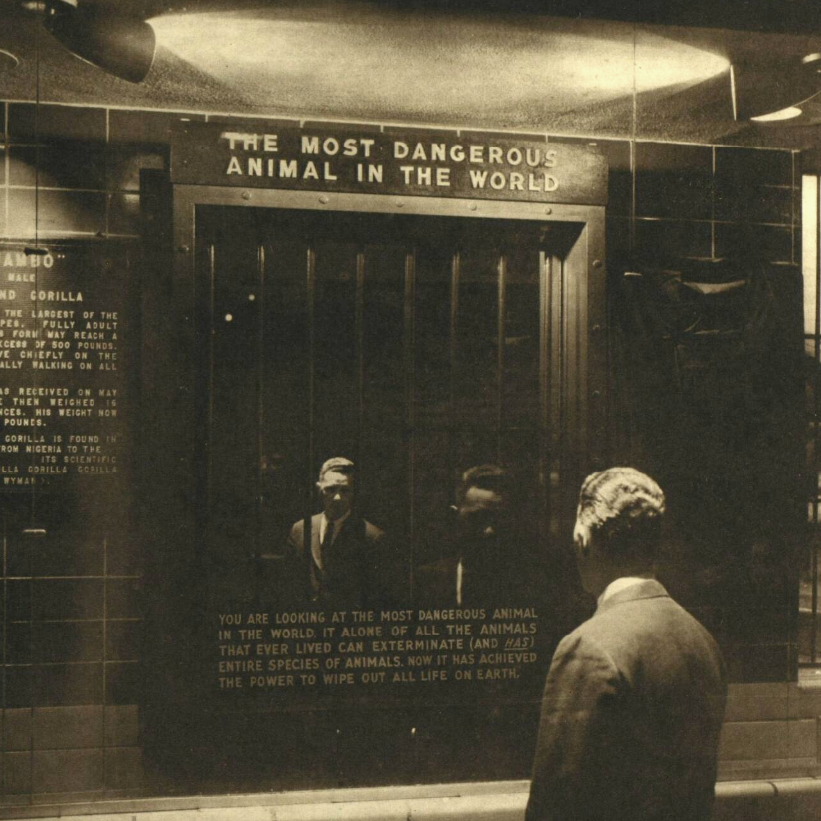

The performance-installation entitled “Reflection”, which depicts man as “The most dangerous animal on the planet”, is reminiscent of the 1963 exhibition at the Bronx Zoo in New York, where a mirror was placed between two animal cages with the text “The Most Dangerous Animals in the World.” Anyone who read the text would see themselves in that mirror. The installation with a chair is not only superficially reminiscent of this 1963 exhibition, but its title, “Reflection”, seems even more suited to the former, which incorporated an actual mirror.

There are many fish-installations all over the world, which have different types of waste in their stomachs. These “fish” are mainly placed near

New York, Bronx Zoo, 1963․

bodies of water, serving as garbage cans, to some extent helping to solve the problem of pollution in coastal areas. It is possible that the Goldfish featured in this exhibition will also serve a similar function in the future.

Thus, the exhibition “Turn Plastic Waste Into Art” leaves out a number of stages in the artistic process, placing the emphasis on well-worn and ubiquitous suggestions instead. In the case of the other exhibition, the organizers seem to be aware of this problem and, before finding and offering solutions, have made discussion as their starting point: in other words – contemplations without answers.

Curated by artist Edgar Amroyan, the “Polyphonia” exhibition was held on October 22, 2021 during the Annual Festival of Installation Art at the Armenian Center for Contemporary Experimental Art (otherwise known as NPAK). This show approached the issue of our environmental crisis from a completely different, non-productive and consumerist point of view․ Although the material used is the same—waste—this and the previous exhibition follow entirely different discourse vectors. Giving reign to consumer tendencies, the first exhibition stressed the importance of the end result created by artistic means. Meanwhile, in Edgar Amroyan’s project, the emphasis is on the reflective aspect of the creative process itself. To speak about waste or through waste: this is the key proposal of the “Polyphonia” exhibition. Waste is not only the subject matter here, but also the motivation to review artistic processes and issues themselves.

This tendency is already evident in the text of the exhibition’s open call. The statement reads, “Taking the material of the project—industrial waste—as the only precondition, artists will be given the freedom to choose the theme and the form of their installation.” It then emphasized that it is not at all important to create installations that raise environmental issues․ “Although the idea of working with waste came from environmental issues, the exhibition should not be limited solely to that topic. The artworks created through workshops and exchanges with the curator can raise a number of important social issues, touching on discourses of inequality, politics, culture, women’s or special groups’ rights, etc.”

Unlike “Turn Plastic Waste into Art”, there are no prepackaged decisions and formulae in “Polyphonia”; instead, a field for dialogue has been created. While the former exhibition sounded-out questions that pertained to humanity at large, the dialogue in “Polyphonia” unfolds within a more specific framework: between artists. The artist does not position herself as an authority or an expert, nor does she try to advise: “What is its solution? I honestly don’t know. And I don’t believe that any foreseeable solutions exist,” says the curator in his text. The artist herself, as a resident of planet Earth, as a person, has many questions, “For me personally, the artist’s irony, pain and concern become the only hope”, states the curator.

Of course, it is difficult to determine to what extent the artists live up to the hopes of the curator or the spectator. However, at least in this exhibition, there are multifaceted approaches to the subject matter which can serve as a means to form new ideological perceptions about the ecologically changing future. That, in itself, is already an objective and constructive result.

Although there were no thematic restrictions on the installations, most of them addressed environmental or related issues in one way or another, such as: Ruzan Petrosyan’s “If the Flower”, Lilit Stepanyan’s “180” and “But”, Narek Hakobyan’s “Eternity”, and others artworks. While the exhibition’s overall objective is not the discovery of answers to the aforementioned ecological problems but, rather, an initiation of conversations about them, the artists do point to some environmental solutions in the first two instances. Ruzan Petrosyan, for example, suggests in her piece that, “The real flowers in the video reflect the flower made of fabric, and the message is that, if we take care of it, we will have the flower in the video. If we do not take care of it, we will have artificial flowers hanging on the wall.”

In contrast, Stella Grigoryan’s work “You, Only You, I Invite to a Dance – Urbanized…”, has nothing but the artist’s ruminations. On the one hand, she praises industrial production, while, on the other hand, she rejects it as an artist. In this installation, the sculptures made of styrofoam and the elements of consumerism—cash register receipts—seem in harmony, and the artist is a part of that reality. This is in line with the overall intents of the exhibition, and follows the logic of the curatorial text. “An installation created from waste is doomed to be aesthetic, even if it is visually unaesthetic, because it gives waste a second life, creating a modern harmony, which may be a faint echo of the harmony of distant times.”

On the whole, aestheticism has strangely been brought back into the sphere of contemporary art in this exhibition. Yet, this not as an end goal (as in classic art), but a tool through which it is possible to transform consumer drives and their “emissions”, as in Stella Grigoryan’s “And That, This, That, That, This, That, Other” and Hakob Balayan’s “The Dreamer”. According to Hakob Balayan, the message of “The Dreamer” is that people should start dreaming again. “When you dream, when you see some beauty, it gives you hope and you start to move, to do something.”

Stella Grigoryan also talks about dreaming, beauty and aesthetics in an interview about the exhibition. “Art helps a person to dream, to think, to continue, to relax. But this general noise, the waste scattered throughout the city, in the villages, and in nature, stops our desire to dream.” As a counterbalance to consumerism, the artist offers the aesthetics of the artwork. According to Grigoryan, the artist must always give an aesthetic solution to heavy issues such as pollution.

But must an artwork be aesthetic, or what, after all, is the key mission of art? Mariam Energetic’s installation “There are Black Clouds Above My Head”, which presents a big black polyethylene bag as a cloud, opens a dialogue around these questions still percolating from the days of Marcel Duchamp. Here, Energetic bluntly manifests the essence of installation art, by taking the object out of its original context, depriving it of its innate meaning and functions, and reassigning a new sensory and philosophical significance to it. In this work, there is no “practical” fix to problems or a new invention for waste transformation. The recycled object doesn’t even function as a site of aesthetic pleasure. However, the black polyethylene bag is powerfully metamorphosed into a SIGN; using almost poetic means, the artist transforms not so much the object as its pictorial and epistemological perceptions. Influencing the viewer’s consciousness, the artwork does not turn the bag into another practical object, but converts it into a signal full of new semantic charges, which, when encountered on a daily basis – in addition to our urgent need to get rid of trash – may also raise feelings of ecological disaster, the danger of consumerism and horrifying feelings of impending disaster.

Thus, these two simultaneously-held exhibitions utilizing the same material, appear with different contents, perspectives and tendencies. One presents issues and offers practical and somewhat simplistic solutions. The other, takes as its starting point the need to have a conversation about artistic issues, pointing to contemporary art’s primary function: not the practical redefinition of matter, but the transformation of the latter’s epistemological and symbolic connotations within our individual and collective consciousness. Both exhibitions are important in today’s reality as intellectual and creative attempts to address the impending issue of daily waste—something that unfortunately remains outside of Armenia’s current agendas. Despite their differences, these initiatives demonstrate the ways in which both design and contemporary art can play a tangible role in responding to the devastating effects of consumerist culture.

“If the Flower”, Ruzan Petrosyan. Photo by NPAK.

“The Dreamer”, Hakob Balayan. Photo by NPAK.

“I invite you, only you to dance, urbanizational …”, Stella Grigoryan. Photo by NPAK.

“Et cetera, this, other, other, this, that, other “, Stella Grigoryan. Photo by NPAK.