Armenia inched closer to consolidating the basic tenets of its security diversification in October, as the overarching Western pivot in its foreign policy orientation and its rupturing of the Russo-centric dependence structure produced concrete outcomes in the formulation of Armenia’s nascent security architecture. With the fallout from the ethnic cleansing of Nagorno-Karabakh shaping the Euro–American posturing against Baku, at least diplomatically and rhetorically, Armenia further deepened its relations with Europe, while the United States confirmed further humanitarian and diplomatic support. This was supplemented by Armenia’s expansive de-Russification of its security architecture, which had initially begun with procurements of arms from India, but became robustly consolidated with further strengthening of security arrangements with France and the signing of an arms deal. Armenia further enhanced the diplomatization of its security by ratifying the Rome Statute and joining the International Criminal Court, a strategic international instrument that can augment Armenia’s growing diplomatic toolkit.

The confluence of Armenia’s Western pivot and security diversification are constitutively linked and part of the broader design of Yerevan’s post-2022 foreign policy orientation. Contextually, the developments in October are extensions of the year-long decoupling from Russia that Yerevan began, with a Western pivot designed to allow Armenia to not only escape the trap of Russia’s dependency structure, but also to attain security independence through security diversification. The Western pivot, to this end, and the geopoliticization of democracy, is neither ideational nor conceptually geopolitical, but rather, a byproduct of a dire security environment and Russia’s abdication of treaty obligations. In the most basic of terms, Armenia is not pivoting West because it wants to make geopolitical moves, but rather, it simply wants to survive. The objective of the Western pivot, to this end, is not the replacing of one dependency structure with that of another, but rather, rupturing the entire logic of dependency and establishing sustainable security independence. With Russia unwilling to support, more to the point, obstructing the process of Armenia achieving security self-reliance, Yerevan had no option but to pivot away from Russia, and as such, pivot West to achieve security diversification. Amalgamating the methodological technique of foreign policy analysis (FPA)[1] with security studies, this report will trace the continuum that explains the structure and dynamics of Armenia’s Western pivot and the extent to which this pivot is an intrinsic necessity to achieving security diversification.

Russia’s False Promise of Security and Perpetuation of Asymmetry

While the collapse of the Russian-led security architecture in the South Caucasus immensely deteriorated Armenia’s security environment, it was the formation of the Russo-Azerbaijani axis and Russia’s abdication of its security obligations towards Armenia that triggered the Western pivot. Refusing to either arm or protect Armenia, Russia simply reified the power asymmetry between Armenia and Azerbaijan by giving Armenia a false promise of security, only to abandon Armenia at its most dire time of need. More so, while Azerbaijan continued to procure arms to increase the power asymmetry with Armenia, Russia refused to meet its treaty obligations of providing arms, at any level, that would allow Armenia to have the most minimal deterrence capability. In truth, Russia tied both of Armenia’s arms behind its back and fed it to Baku. Armenia’s greatest source of insecurity became its reliance on Russia for security.

To fracture this unreliable and abusive reliance, Armenia had one option: to attain hard power capabilities from alternative sources. Access to alternative sources, however, especially after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, placed Armenia within a conundrum: access to weapons from Western countries remained impossible for a “Russian satellite.” Thus, Armenia’s military relations with Russia had become a dangerous liability: stick with Russia and be fed to Baku on a silver platter and have no chance of procuring hard power capabilities. As an initial stop-gap measure, Armenia sought access to weapons from India, but noting the excessive power disparity with Azerbaijan, a singular source of procurement remained insufficient. Thus, a broad diversification of access was necessitated. To operationalize such a diversification, Armenia not only had to decouple from Russia due to the latter’s lack of credibility as a security partner, but also had to pivot West to have access to alternative sources. In this context, the Western pivot was not simply a foreign policy restructuring; more than that, it was a pre-emptive move designed to enhance Armenia’s chances of diversifying its security and being able to procure hard power capabilities. Without a Western pivot, Armenia would have no chance of mitigating the power disparity with Azerbaijan. For this reason, the Western pivot was a foreign policy move designed to address Armenia’s impossible security situation.

Pivoting Through Decoupling

The decoupling from Russia, in this context, is a move towards security independence, which can only be achieved through security diversification and an escape from Moscow’s dependency structure. Moscow’s subsequent political and diplomatic attacks are clear reactions against Armenia for precisely undertaking such a pivot towards security self-reliance. In this context, Armenia’s refusal to participate in CSTO military exercises, or partake in the CIS summit, or decline to house the Russian peacekeepers once they leave Nagorno-Karabakh, or to even question the continued presence of Russia’s military bases in Armenia, are part of the process of developing an independent security architecture: to be able to diversify its security, Armenia must decouple from Russia in the security sphere.

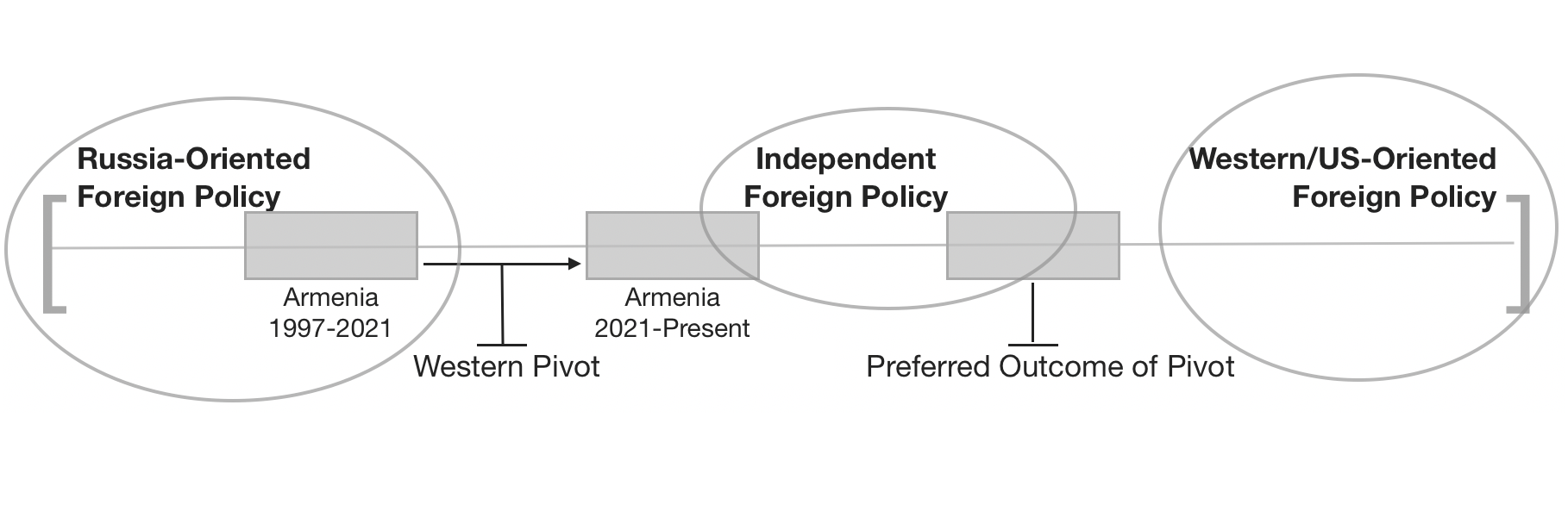

This process of decoupling, and as a result, pivoting, qualifies the initial shift away from Russia’s orbit in the continuum. Noting the structuration of the continuum, and the policy orientations on the two ends, the shift away from Russia’s orbit is qualified as a Western pivot. Thus, the pivot is directional, not ideational, as previously noted. Any qualitative move away from Russia’s dependency structure is a directional shift towards an “independent” foreign policy. Independent foreign policy is qualified here as the ability of a state to address its diplomatic and security needs through self-reliance while possessing sufficient capabilities to unilaterally exercise agency. Independence, however, does not mean that the given state refrains from having partners or strategic allies; rather, it denotes that strategic alliances and partnerships supplement and strengthen a given state’s self-reliance, but do not constitute a dependency structure. In this context, an independent foreign and security policy is defined as the ability of a state to exercise and prioritize its national interests in coordination with strategic partners.

As the continuum demonstrates, Armenia’s foreign and security policies from 1997 to 2021 were positioned within Russia’s orbit, but with Russia’s failures to address Azerbaijan’s incursions into Armenia-proper in 2021, Armenia slowly proceeded to develop the groundwork for a potential pivot. After the Jermuk invasion by Azerbaijan in September 2022, and Russia’s complete refusal to meet its security obligations, Armenia operationalized its Western pivot policy. In this context, the causal variable for the shift away from Russia’s orbit and into the periphery of an independent orbit is the Western pivot policy. The preferred outcome for Armenia is the continuous shifting in the continuum towards a fully independent foreign policy that borders the Western orbit’s periphery. But the policy orientation refrains from extending the pivot into the Western orbit, hence the qualifier of refusing to transition from one structure of dependence (Russia) to another structure of dependence (West/U.S.). As such, the objective of the Western pivot is to robustly shift away from the Russian orbit into a fully independent orbit, with sets of strategic partnerships with Western or non-aligned actors. Further, in the case of Armenia, there is a direct positive correlation between pivoting West and having bigger access to procuring hard power capabilities. To this end, there is a robust relationship between the directional pivot and security diversification. Further, the Western pivot does not entail complete severing of relations with Russia, but rather, only a rupture of the dependency structure.

Within this analytical framework, Armenia’s Western pivot is defined by three pillars: 1) pivoting away from Russia entails a Western trajectory on the continuum, but the shift is towards strategic independence and is thus directional, not ideational; 2) the pivot neither seeks to harm Russian interests or advance the West’s interests, but rather, to advance Armenia’s interests by addressing the severity of the security dilemma, and as such, it is designed to effectuate security diversification; and 3) the pivot endeavors to rupture the structure of dependence that Armenia has suffered under for the last two decades, and by extension, disrupt the “great power savior complex” so common to decades of foreign policy thinking in Yerevan.

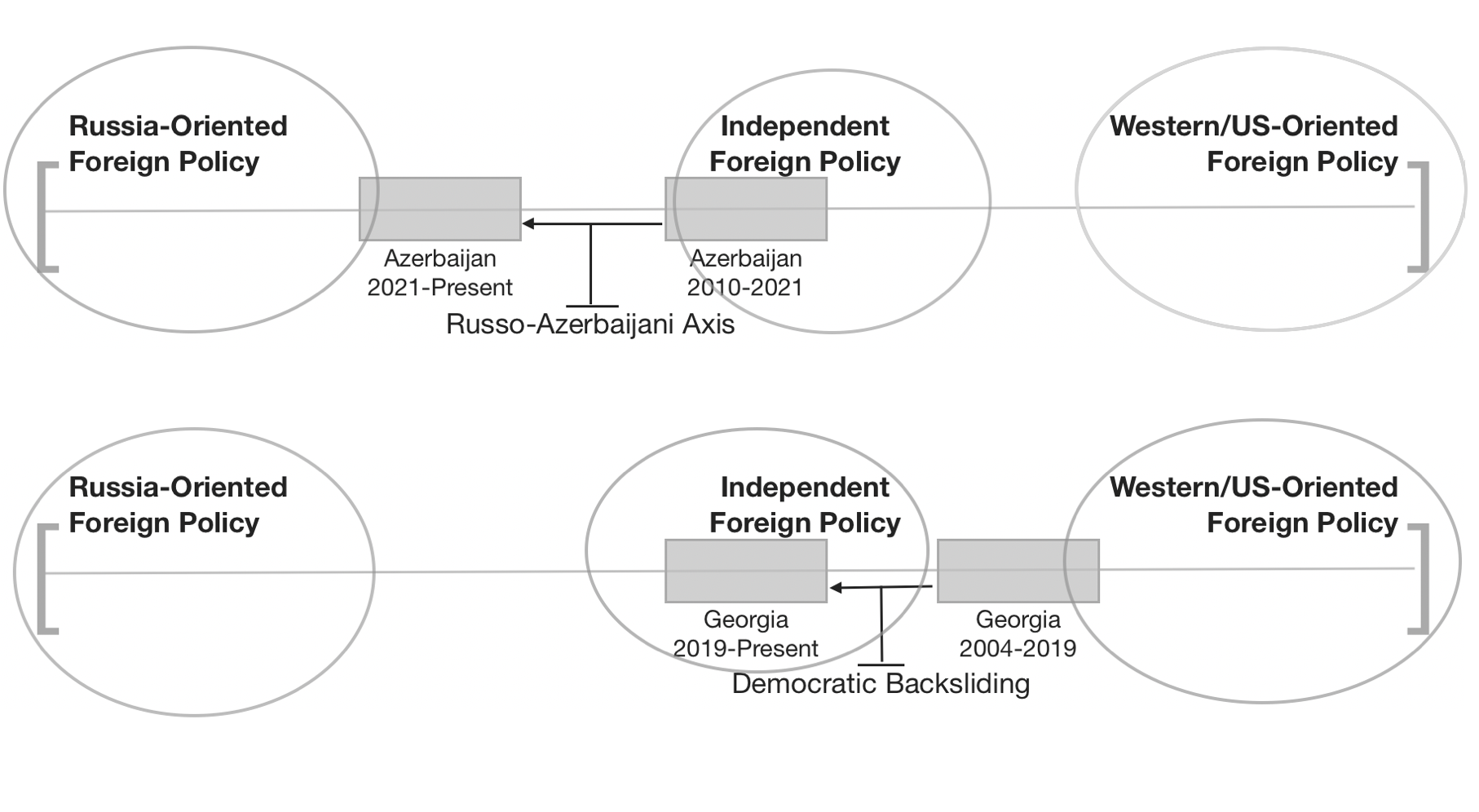

Applying comparative foreign policy (CFP) analysis at the cursory level, continuums for Azerbaijan and Georgia are also constructed in order to gauge pivotal trends in the region. When gauging Azerbaijan’s foreign and security posturing in the continuum, Baku maintained a relatively well-balanced independent foreign policy for over a decade (2010-2021), as it slightly tilted towards the Russian sphere to demonstrate homage to the regional hegemon, yet refraining from falling into Russia’s orbit. Azerbaijan’s alliance with Turkey is qualified in the continuum within the “independent” orbit, since Baku’s relationship with Ankara is not based on sphere-of-influence dynamics, but rather one of Ankara aiding and abetting Baku’s objectives. In this context, a generally mutual alignment of interests defines the two states, which permitted Azerbaijan to maintain a level of independence that allowed it to avoid falling into Russia’s dependence structure. After the 2021 incursions into Armenia-proper, and the formation of the Russo-Azerbaijani axis, Baku pivoted towards Russia in the continuum, yet stopping at the periphery of Russia’s orbit, and thus not falling within Russia’s sphere of influence. However, it is more than evident that Azerbaijan has robustly shifted, directionally, towards the Russian axis, and by extension, away from the Western axis. In this context, while Armenia has directionally pivoted West, Azerbaijan has pivoted towards Russia. The causal variable for Azerbaijan’s pivot, quite clearly, is the formation of the Russo-Azerbaijani axis and Russia’s proxy-ization of Azerbaijan vis-a-vis Armenia. To this end, there’s a positive correlation between Azerbaijan’s aggressive behavior in the region and its pivot towards Russia’s authoritarian orbit.

Georgia’s positioning in the continuum was defined by its presence in the periphery of the Western/U.S orbit from the Rose Revolution in 2004 to the growing democratic backsliding that began in 2019. In this context, Georgia’s positional shift from being in the Western orbit for 15 years to a more independent foreign policy orbit has been a directional pivot away from the West. Georgia’s post-2019 presence on the continuum demonstrates a tactical shift that is structurally similar to Azerbaijan’s positioning from 2010 to 2021: a tenably healthy relationship with Russia, but nowhere close to being absorbed into Russia’s orbit, and in the same light, a cordial, if at times tense posturing vis-a-vis the West, yet being sufficiently outside of the Western orbit. Interestingly, whereas the causal variable for Armenia’ pivot is security diversification, while Azerbaijan’s causal variable is geopolitical realignment, Georgia’s pivot is primarily defined by domestic political configurations: democratic backsliding. Considering how the continuum’s Russia-West dichotomy correlates with a liberal-illiberal dichotomy, Georgia’s directional pivot is positively correlated with the ruling Georgia Dream party’s illiberal shift. Contextually, while Georgia, right now, exercises the most independent foreign policy in the South Caucasus, its pre-pivot position in the continuum is precisely what Armenia is aspiring for. To this end, democratization and independent foreign policy positionally place a state in the independent orbit, yet at the periphery of the Western orbit; illiberalism and independent foreign policy, on the other hand, positionally still places a state in the independent orbit, yet closer to the periphery of Russia’s orbit.

Conclusion

The rearticulation of Armenia’s new foreign policy direction, primarily defined by an unequivocal need for security diversification, in what has been qualified as a Western pivot, has been the subject of much misunderstanding and misinterpretation by pundits, commentators and pseudo-analysts within Armenia. With the exception of Western-trained academics and a set of practitioners in Armenia who boast field experience and knowledge, much of the “analysis” has been conducted by untrained observers who lack sufficient scholarly, methodological and advanced analytical training. By failing to conceptualize and cogently comprehend the three main pillars of the Western pivot, and more specifically, to qualify the pivot within a set continuum, many observers have qualified the new foreign policy direction through three flawed observations: 1) the pivot seeks to sever all ties with Russia; 2) the pivot seeks to replace one structure of dependency (Russian) with another structure of dependency (West/US); and 3) a zero-sum conceptualization of the pivot, as opposed to a dynamic and continuous configurations. Considering the sensitive and complex nature of the pivot, the general failure of Armenia’s “pundit class” has been its natural default to conspiratorial thinking, abstract pontification, and an intrinsic, if not a subconscious need, to politicize every development. The result has been an underdeveloped treatment of the relationship between the Western pivot and security diversification.

Twenty-five years of foreign policy failures, from the incoherence of complementarity of the Kocharyan Administration to the faux multi-vectorism of the Sargsyan Administration produced three structural outcomes that incapacitated the Republic of Armenia from pursuing an independent foreign and security policy: 1) Russia as the source and determining actor of Armenia’s security and foreign policy; 2) prioritization of Russian strategic interests over Armenia’s national interest; and 3) Armenia’s isolation from regional and international developments, with Armenia being primarily qualified as a Russian satellite. The complete deprioritization of seeking Armenia-centric outcomes, due to the fear that it may contradict Russia-centric preferences, reduced Armenian foreign and security policy thinking to one of subservience: do not exercise agency lest you upset the Russians. Russia’s false promise of security, and Armenia’s complete structural dependence on Russia, became the perfect recipe for security failure. Thus, with the collapse of Russia’s pivotal deterrence policy, Armenia’s utter inability to address its security dilemma due to its structural dependence on Russia (extended deterrence policy), and Russia’s abdication of all treaty obligations in the face of Azerbaijan’s incursions into Armenia-proper, Armenia’s security environment became untenable. The Western pivot, in the face of all such developments, is simply a new foreign policy direction designed to address a desperate need: security diversification.

[1] Primarily utilizing the rational actor model and the inter-branch politics model, with interchangeable operationalization of content analysis and “third generation methods.”

Examining the Context

Examining the Context: Security Independence Through Security Diversification

EVN Report's Editor-in-Chief Maria Titizian speaks with Dr. Nerses Kopalyan, author of the monthly series "EVN Security Report" about the objective of Armenia's Western pivot, which is neither ideational nor conceptually geopolitical but rather the need to rupture the entire logic of dependency and establish sustainable security independence for the Republic of Armenia.

Read moreEVN Security Report

EVN Security Report: September 2023

The status quo established by the Russo-Azerbaijani tandem in Nagorno-Karabakh completely broke down after Baku launched a massive invasion of Artsakh while coordinating operations with Russian forces. This culminated in the collapse of the Artsakh Republic. Nerses Kopalyan presents an in-depth analysis of developments.

Read moreEVN Security Report: August 2023

The madman theory is a strategy in coercive bargaining, where the perceived extremism of an actor is leveraged to achieve one-sided outcomes. Aliyev’s bargaining posture operates off of the logic that if his terms are not met, he reserves the right to wage war, thus anchoring the threat of destruction to force acquiescence from Armenia and the international community.

Read moreEVN Security Report: July 2023

Critical self-reflection is necessary as Armenia overhauls its intelligence infrastructure. For national security strategy to be concrete, substantive and operationalizable, it requires strategic intelligence. Nerses Kopalyan explains.

Read moreEVN Security Report: June 2023

In this security report, scenario planning is fused with contingency planning to prepare courses of actions and outcomes that may address unexpected situations and mitigate significant impact to Armenia due to the ongoing Russia-Ukraine conflict and its effect upon Russia’s domestic political order.

Read moreEVN Security Report: May 2023

Armenia’s vast mines have never been part of its security architecture, nor has the potential securitization of this sector ever been considered a fundamental cornerstone of building alliances or strategic partnerships. Mining-for-security should not be qualified as a political act, but rather, a fundamental security act, Nerses Kopalyan writes.

Read moreEVN Security Report: April 2023

Russia’s refusal to either enforce or impartially implement the terms of the November 9 tripartite statement that ended the 2020 Artsakh War has generated a growing cleavage between Armenia and Russia, revealing Moscow’s preference for frozen conflict persistence.

Read moreEVN Security Report: March 2023

The region’s security arrangement remains in flux as Azerbaijan amplified its rhetorical aggression and engaged in expansive troop movements and build-up in border areas. Greater Western involvement has deepened the alliance between Azerbaijan and Russia. While Moscow and Baku have established a united front against the West’s presence in the region, Armenia has proceeded to reconfigure its strategic interests, advancing its democracy narrative, while aligning its preferences to the resolution of the conflict with the Western-led stabilization efforts.

Read moreSee all Security Reports